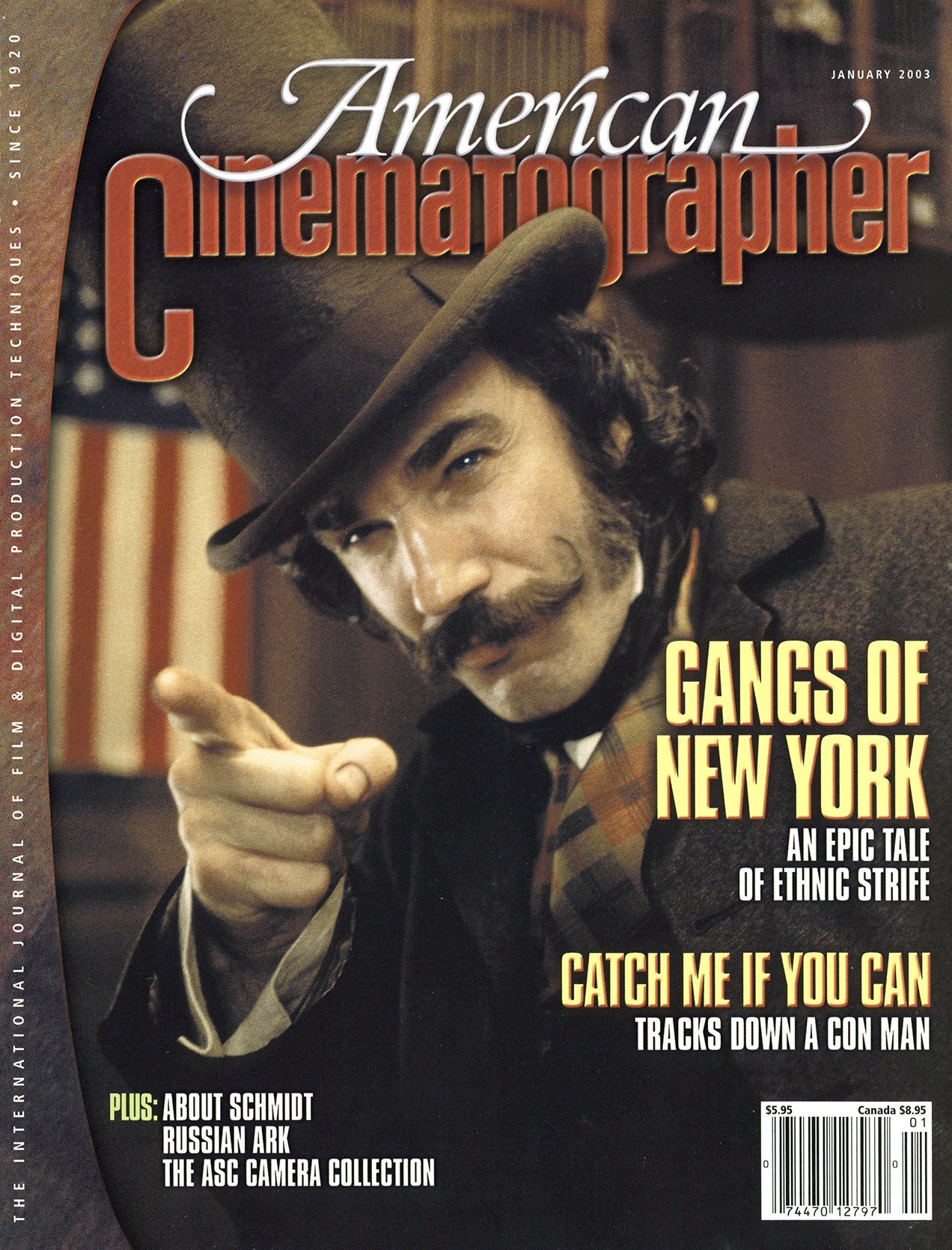

Gangs of New York: Native Sons

Michael Ballhaus, ASC, BVK takes on Martin Scorsese's Gangs of New York, a 19th-century tale of vengeance and valor set in the city's most notorious neighborhood.

Unit photography by Mario Tursi.

Additional photos by J. Patrick Daily

By the time Martin Scorsese teamed with cinematographer Michael Ballhaus, ASC, BVK for the first time, on the 1985 film After Hours, Scorsese had been thinking about a very different New York story for a number of years. It was set during an especially tumultuous period of the city’s history, and much of the action took place in the area surrounding Scorsese’s boyhood home in Lower Manhattan. The story was Herbert Asbury’s 1928 book The Gangs of New York, a hair-raising account of the criminal activity that shaped life in New York in the 19th century. Subtitled "An Informal History of the Underworld," the book details a city swirling with vice and corruption, where dozens of gangs protected their turf with brass knuckles and brickbats while most authorities looked the other way. It was a world that was continually reshaped by waves of immigrants; many of the gangs formed along ethnic lines, and turf wars were fierce.

“Nowadays, you rarely have the opportunity to work with a wonderful director, an excellent script, the perfect cast and a production designer who tailors everything to your needs. The combination of all those things creates an unbelievable situation for a cinematographer.”

— Michael Ballhaus, ASC, BVK

According to Asbury, New York’s most fearsome gangs were headquartered in the Sixth Ward, an area bounded by the Bowery, Broadway, Canal (then Walker) and Chatham. Today part of Chinatown, the neighborhood was at that time crowded with Irish, German, Jewish, Chinese and Italian immigrants, who lived alongside a small community of African Americans. The hub of activity – criminal and otherwise – was Five Points, an intersection of several busy streets at the corner of a park called Paradise Square. As immigrants continued to pour into the neighborhood, Five Points became renowned for overcrowded, squalid tenements and pervasive crime; saloons, brothels and gaming halls flourished, and con artists and thieves preyed on those who ventured from Bowery dance halls into the streets nearby. By the middle of the 19th century, Five Points was widely considered to be the world’s worst slum. "Every house was a brothel," noted one visitor, "and every brothel a hell."

Compelled by a keen interest in New York history, Scorsese put Asbury’s book on his "wish list" of projects when his career took off in the 1970s. But the period epic clearly required a substantial commitment of time and money, and it took almost 30 years for the necessary elements to fall into place. During that time, Scorsese collaborated with Ballhaus on four more films: The Color of Money, The Last Temptation of Christ, GoodFellas and The Age of Innocence (see AC Oct. ’93). "Marty and I talked about Gangs of New York from time to time over the years, but it never seemed to be possible," Ballhaus recalls. "It was not an easy project to get off the ground."

A Chaotic Canvas

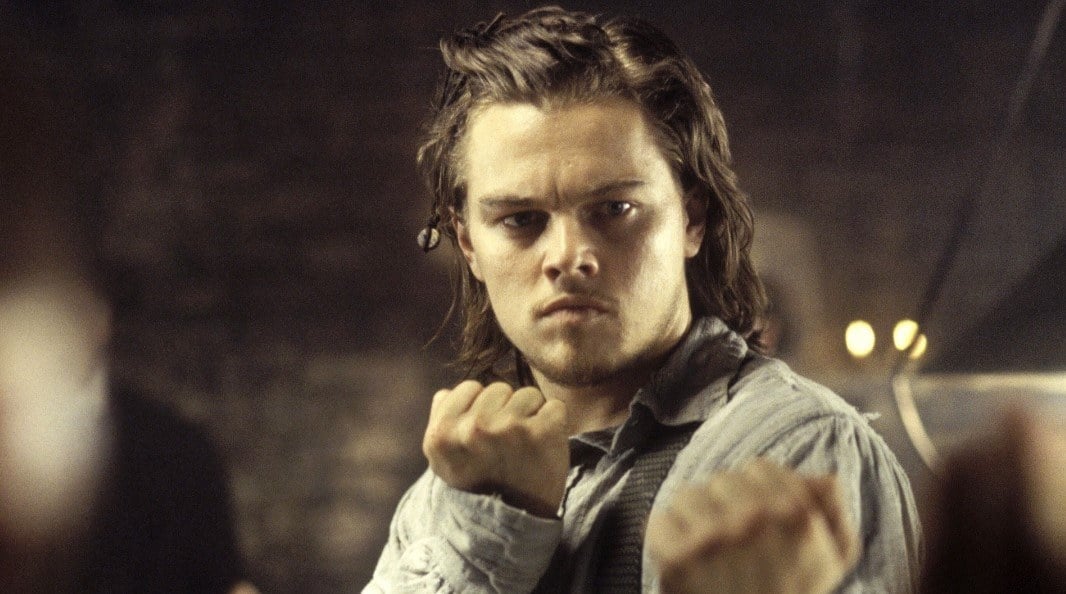

In adapting Asbury’s book for the screen, Scorsese and a team of screenwriters narrowed its scope to 1840-1863, an especially turbulent period in Five Points history. A famine in Ireland in the 1840s led to an explosion in Irish immigration to America, and the years preceding and encompassing the Civil War saw fierce rioting throughout New York, much of it downtown. Gangs of New York focuses on Amsterdam Vallon (Leonardo DiCaprio), a young Irish-American who returns to Five Points after spending 15 years in reform school following the death of his father (Liam Neeson). Vallon is bent on avenging his father’s murder, which occurred at the hands of Bill the Butcher (Daniel Day-Lewis), a Nativist gang leader who rules Five Points with an iron fist and a wicked blade. The Protestant Nativists clash regularly with the growing numbers of Irish Catholic gangs, and when Vallon begins rallying his fellow Irish to join forces and challenge the Nativists for control of Five Points, the action culminates with a bloody showdown during the Civil War Draft Riots of 1863.

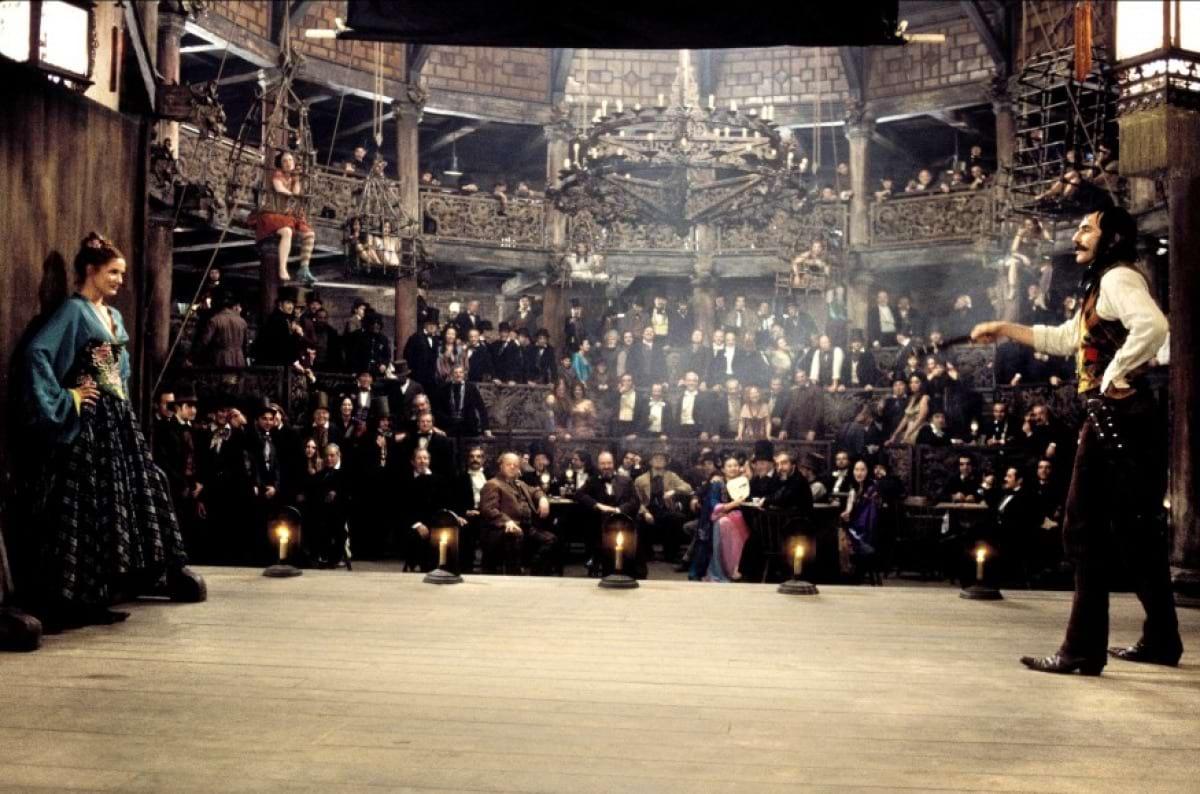

Gangs of New York was filmed at Cinecittà in Italy, where production designer Dante Ferretti and his crew built the one-mile-square Five Points neighborhood and other sections of Manhattan from scratch on the studio’s 99-acre lot. Key set pieces included the Old Brewery, a massive tenement that dominated the Five Points intersection; a Chinese-pagoda-style theater/brothel; and a section of the city’s waterfront. "The set design was clear from the beginning and everything was built," Ballhaus recalls. "Although a few elements of the set were added later, we knew which locations we had to have well in advance."

Ballhaus and Scorsese had eight weeks of preproduction before principal photography began in September 2000. "It wasn’t a very long prep for a movie like this, especially for Marty, who was still working on the script," Ballhaus says. "Marty prepares very carefully, and he normally has shot lists for everything — on The Age of Innocence, every shot had notes. His notes are always about the rhythm of the scene; he writes what kind of coverage he wants, how many shots he needs and the size of the shots. We had shot lists for this movie, but they weren’t as specific, and we usually developed them on the day we were shooting that material.

"I think we needed at least six more weeks of prep to be really prepared," he continues, "but in a way it didn’t matter because Marty and I know each other so well. We’d just go on the set, watch the rehearsal, look at each other and immediately agree on how to shoot it. It was a different way of working with him, but it was as wonderful as always."

One tool Ballhaus found useful in planning shots was a MiniDV camera, which he had on set at all times. "I’ve used MiniDV for at least 10 years as a notebook, a visual diary," he explains. "I always used it during rehearsals on this show – I could put it down on the floor or hold it up high and experiment with angles, and then I could show the shots to Marty and my crew."

Gangs of New York was filmed in Super 35mm (2.35:1), a format Ballhaus has long favored. "The main reason I prefer it is that I can avoid panning and scanning when the film goes to tape or to TV," he explains. "When you take an anamorphic film to tape or TV, you have to pan and scan, and not one composition or frame is the same as what you originally shot. When I use Super 35, I shoot with a common top and leave the bottom of the frame clear; when I go to tape, I can get fairly close to my original composition by just opening up the bottom of the shot."

Scorsese gave Ballhaus a book of Rembrandt paintings during prep to illustrate the dark, warm look he desired for Gangs of New York. "We considered using the ENR process to achieve the look we wanted, but I did several tests and decided we didn’t need it," the cinematographer says. "If you have a really healthy negative and work with your printer lights, you can get the same rich blacks. Having our entire set built also helped greatly, because we had complete control over the colors. Dante’s crew just painted the buildings the way they would’ve looked at that time – lots of grays, browns and blacks. I knew that printing on Kodak’s Vision Premier would help us, too, because it increases contrast and takes color away a little bit. I love that stock, and its qualities were perfect for this movie."

Another component of the film’s look was the extensive use of smoke, which was true to the period and also helped desaturate colors. "We had smoke in almost every scene, which helped soften the image," Ballhaus says. "Given the period, there was always a lot of atmosphere in the air. There were fires burning all the time, even outside during the day." Throughout the shoot, Ballhaus used Tiffen Black Pro-Mist filters ranging in strength from 1/8 to 1/2, and he occasionally employed Harrison & Harrison fog filters.

The cinematographer shot most interior scenes on Kodak Vision 320T 5277, which he rated at 200 ASA. "When you expose 5277 at 320 it’s pretty flat, but at 200 it gets more contrasty," he observes. "It makes the blacks a bit richer, and I think the gamma changes a little bit. I always expose that stock at 200, especially with Super 35, when it’s important to have a healthy negative because of the optical blowup."

He filmed day exteriors on Eastman EXR 50D 5245. "I never shot higher than T5.6 on day exteriors – I never shoot at high stops – and I always filtered down with ND.6 or ND.9," he says. "I also occasionally used colored grads to darken the sky."

Ballhaus filmed most of the show’s night scenes on Kodak Vision 500T 5279, but for one significant night scene, in which Vallon saves the life of another young Irishman (Henry Thomas) during a house fire, the cinematographer used a method that he and his gaffer, Jim Tynes, had read about in AC. "I wanted the flames to be really rich and red rather than white," Ballhaus says. "We remembered the American Cinematographer story about Mikael Salomon [ASC]’s work on Backdraft [AC, May ’91] and decided to try his idea, which was to shoot fire on daylight stock and light it with HMIs."

"The HMIs were pretty large because we wanted to get the fill level up," Tynes explains. "The idea is to bring the base level up to a pretty high f-stop, allowing you to stop the lens down and prevent the fire tones from bleaching out into the white spectrum. We used as much firepower as we could get, several 18Ks and 12K Pars, which we positioned behind the camera and used as high bounces with 20-bys and 12-bys to create overall ambience. We also had some tungsten units motivated from the building illuminating the scene." Adds Ballhaus, "We shot the scene on 5245, and I used a fairly high stop, T5.6 or T8, to get strong colors. It worked wonderfully."

Throughout the shoot, a soft wash of ambient moonlight was provided by a giant softbox designed by Tynes and key grip J. Patrick Daily, who were among the few key crew members Ballhaus was able to take to Italy. (The others were camera operator Andrew Rowlands and first assistant Thomas Lappin.) "We had a lot of night exteriors, and when we started prepping the movie I asked Pat and Jim to come up with a large, movable light source that could give us a soft moonlight," Ballhaus says. "They came up with a wonderful device."

Daily and Tynes’ creation was a 25-square-foot softbox that held 12 to 15 12-light Maxi-Brutes aimed through light gridcloth; the entire box was wrapped with Ultrabounce to contain spill. The softbox was suspended from a 220-ton DiMag crane with a 93-meter reach. "The set was so enormous that we needed something to separate the rooftops, and by moving the giant softbox around the set we could maintain a consistent three-quarter backlight," Daily explains. "It weighed about 4,000 pounds, and we needed two cranes to move it — one would hop it over one row of buildings, and then the other would pick it up and hop it over the other row. We had to plan with military precision, because once it was in place the only flexibility we had was what we could get by swinging the crane arm around. Moving the softbox to the opposite side of the set — not to mention setting up the electrical service that had to go with it — took a lot of time. Fortunately, Michael and Marty have such a good relationship that Michael knows where the camera will be looking well in advance of the shooting day, so we always knew where the softbox needed to be."

Another source for night scenes were dozens of period streetlamps, which had been rigged for electricity and gas while the set was built. "All of the necessary cabling was run under the streets and sidewalks months before principal photography started," says Tynes, who joined Daily for one week of "preliminary prep" at Cinecittà in June of 2000. It was during that week that the two hired their Italian counterparts, gaffers Patrick and Alex Bramucci and key grip Tommaso Mele. "We weren’t sure that far in advance how we’d be approaching some situations, so all of the streetlamps were outfitted with electric and rigged with gas lines to a real gas burner," Tynes continues. "We put a 2K CYX bulb inside each lamp and put a 5K bulb on the backside of each lamp; each bulb was attached to its own dimmer. The 5Ks worked the large, expansive backgrounds – they could slash the buildings and slash the people – and they were flagged and isolated so you couldn’t see the light from the front. We usually dimmed the 2K bulbs down to 30 or 40 percent so they’d have a rich orange glow, which was very close to the feeling of gaslight. We actually only used gas in the lamps a couple of times, notably after the riot sequences, when cannon fire from the harbor has broken some of the lamps. We had open flame coming out of a few lamps, like a gas-fire explosion, which we played scenes against."

In keeping with the period, interior lighting had to suggest firelight, torchlight and candlelight. "Interior light was always soft and warm, and by attaching the lights to flickerboxes we could keep the light moving, which is an effect I like a lot," Ballhaus says. Tynes often lit interiors by bouncing 10Ks and 5Ks that were on flickerboxes and gelled with full CTO. "We went for the higher-wattage units because I’ve found that the filaments of 10K and 5K lamps behave differently on the flickerbox than the filaments of smaller units," says the gaffer, who first teamed larger units with flickerboxes while working with Ballhaus on Bram Stoker’s Dracula (AC Nov. ’92). "With a larger light, the flickerbox has a slower attack and slower decay as the filament is turned on and off; it takes a while to come up and cool down, so you can shape the firelight effect a certain way. You can shape a Par light or something else with a relatively fast filament, too, but it requires a lot more finessing to make it believable. If you have room in your set to deal with a larger unit, you’ll end up with more believable firelight."

One of the show’s largest interiors was a Chinese pagoda that, true to the style of the times, functioned as a live-entertainment theater, brothel, bar and gaming house. The three-story set was shaped like a pentagon, and hanging over the atrium at the center was a massive candle chandelier, which was the set’s key light source. To mimic the soft overhead light, Ballhaus’ crew used sources they had created while working with the cinematographer on Air Force One. Tynes explains, "On Air Force One, there was a large, formal dinner in a practical location where we couldn’t do much rigging. Michael didn’t like any of the standard solutions for lighting the space, so Pat Daily designed – and Charles Norcross and my best boy, John Sandau, created – some 10K China balls about 4 feet in diameter, and envelopes of full and light grid to go around them. We’ve used them a number of times since Air Force One, and we had two or three of them hanging in the Chinese pagoda, each on its own dimmer. Because Italy is on the 220-volt system, we could actually put 20K bulbs in them and simply change the connector; that gave us a lot of flexibility and a lot of light."

Fight and Flight

Throughout Gangs of New York, Scorsese and Ballhaus use a highly mobile camera and a variety of in-camera effects to visually underscore the instability and excitement of the period. "Every shot is moving," Ballhaus confirms. "Sometimes they’re just little sideways moves with a handheld camera, but the camera is always in motion. We also varied our frame rate, which we’ve done a lot in the past. We shot some battle scenes at eight frames per second; sometimes we step-printed them four times to create a strobing effect, and other times we didn’t print them up. We often used speed changes — going from 24 fps to 30 or 32 fps — to underscore significant moments. Marty created a similar effect with editing patterns as well."

Ballhaus’ Arriflex camera package consisted of 535As, 535Bs and 435s, and he photographed most of the show with Zeiss Variable Primes. "I love the VariPrimes because their quality is excellent, and if you want to go a little wider or a little closer it’s just a move of the finger," he says. "I like to move forward or back a little and use little zooms." He also used a set of Zeiss Ultra Primes, an Angenieux 5:1 zoom and a Cooke 10:1 zoom. "We didn’t want an extreme or modern look because that wouldn’t have suited the period, so I mainly used lenses ranging from 18mm and 135mm," he notes.

As many as eight cameras were used on battle scenes, and second-unit director Vic Armstrong and second-unit cinematographer Florian Ballhaus (Michael’s son) were responsible for many of those sequences. "There’s a lot more coverage in this film than Marty and I normally do," the senior Ballhaus acknowledges. "But on a movie of this size you have to cover yourself and think ahead. This was actually the best experience I’ve ever had with a second unit — they shot a lot of material, and it matched our material perfectly."

Cranes were used to accomplish a number of dramatic camera moves, and one particularly remarkable move was accomplished with a length of cable, two construction cranes and a Range Rover. The shot caps the bloody showdown in which Bill the Butcher murders the senior Vallon, and it begins with a close-up of Vallon’s face after his body is loaded onto a wagon. Scorsese wanted the camera to gradually pull back to reveal all of Paradise Square, then all of Five Points, and finally all of Manhattan and the wilderness beyond. "We knew that 90 percent of the landscape would be CG, but we had to initiate the move and bring the camera up to a certain height to show our set," says Daily, who was charged with building a rig to facilitate the shot.

A 75' Akela crane located in France was ruled out because the production’s shifting schedule made it too difficult to lock down the crane’s availability. "In retrospect, the Akela probably wouldn’t have been the right piece of equipment, because 75 feet isn’t much of a reach when your set is acres in size," Daily notes. His next idea was to table-mount the camera and use a construction crane to pull it back. "Italy has a lot of really good cranes and we used them often, but Michael wasn’t comfortable with that plan because he was concerned about the rig’s vulnerability to winds," Daily says. "So I finally decided to make a cable slide and basically slide the camera up to a fixed point."

Daily chalked out the stage floor and made small foamcore cutouts of the Five Points set to show Ballhaus and Scorsese what he had in mind. They approved his idea, and when the production broke for Christmas, Daily returned to Los Angeles, put together the necessary hardware and shipped it to Italy. "When we got back to Cinecittà in January, we built the rig and tested it with a video camera," he recalls. "The Paradise Square set was about 800 feet wide. We put a construction crane on one side of the square and attached the cable to it, about 40 feet off the ground. At the other end of the square, at the high end of the move, we had a 170-foot crane. It was a fairly slack cable, and the idea was that the weight of the camera [which was on a Libra head and mounted on a speedrail sled] would pull the cable taut enough to pull it up and out of the shot. A Range Rover was our power source – Italian key grip Tommaso Mele cued the driver with a radio, and he simply drove down the road to his mark.

"When the time came to film the scene, it only took us two hours to put the rig in place," he continues. "It ended up being about a 700-foot move, and the camera ended up 150 feet in the air. When the camera finally landed you could see all of the set and even beyond, to the stages and off the studio grounds. It worked spectacularly, and it’ll drive me crazy if everyone says, ‘That’s a great CG shot!’"

The film’s climactic action sequence encompasses the Draft Riots, which began as a citywide protest of the Civil War draft order and quickly degenerated into mob violence that devastated the city. The aftermath of the riots called for a technically intricate camera move that required a makeshift bluescreen projection deep in a hole. "It began as a wide shot overlooking what would ultimately be a CG cityscape," Daily explains. "The camera starts about 100 feet in the air, pans across the flaming horizon and then tilts down the face of the Old Brewery, a five-story building that’s now crumbling and on fire. The camera had to tilt down the face of the building and then look straight down at people dumping bodies into a giant hole, which was supposed to have been created by a cannonball that had broken through into the catacombs below the city. The camera was to do a very slow move down toward the hole, and then it would become a CG shot as the camera enters the catacombs.

"We used a construction crane for our move — we cable-slung the Libra head and camera so it was looking straight down," he continues. "It was a night shot because Michael likes to shoot right at the edge of complete darkness, with just a little blue in the sky. We had our giant softbox hanging off to one side, and then Jim Tynes and I had to come up with a way to create a bluescreen projection at the bottom of the hole."

In accordance with visual-effects supervisor Michael Owens’ specifications, Tynes and Daily built an 8'x8' softbox with a milk Plexiglas cover, and they filled the box with Super Blue fluorescent tubes gelled with a combination of full CTB and heavy blue gels. The lightbox was placed at the bottom of the hole, and the art department dressed the edge of it with dirt and debris to suggest the shape of the hole. The bluescreen element was later keyed out and replaced with CG catacombs.

Several months after the production wrapped, the filmmakers decided that they needed to reshoot portions of the climactic battle scene in order to clarify some action. Ironically, these two days of reshoots were the only bit of principal photography that actually took place in New York — on a soundstage at Silvercup Studios in Astoria. "It was the kind of situation that’s an absolute nightmare for every director of photography," Ballhaus remarks. "The scene in question had been filmed more than a year earlier, and it was shot in bright daylight on the Paradise Square set. We had to recreate it on a soundstage with just a few background elements, and we had to do 25 shots in two days.

"We had filmed a different battle scene, one that was filled with smoke from grenades, onstage at Cinecittà, and we tried to take the same approach at Silver Cup," he continues. "We hung a lot of space lights overhead to create the feeling of soft daylight, and then we filled in and had a little key from one side to suggest the angle of the sun. Fortunately, the shots were close, so we used long lenses and just fogged the set in heavily so you couldn’t see much of the background. It was quite difficult, but it worked."

Ballhaus notes that the variety of challenges posed by such a unique project helped make Gangs of New York "a big celebration of moviemaking." He adds, "Everyone involved really wanted to make this movie, and that made all the difference. In a way, it was like a dream come true. Nowadays you rarely have the opportunity to work with a wonderful director, an excellent script, the perfect cast and a production designer who tailors everything to your needs. The combination of all those things creates an unbelievable situation for a cinematographer, and I don’t know if I’ll ever have that again. Everything was right."

TECHNICAL SPECS

Super 35mm 2.35:1

Arriflex cameras

Zeiss, Angenieux and Cooke lenses

Eastman EXR 50D 5245, Kodak Vision 320T 5277, Vision 500T 5279

Printed on Kodak Vision Premier 2393