Hitchcock’s Techniques Tell Rear Window Story

Shooting the script as the director imagined it necessitated the design and construction of a gigantic composite set on which the film was shot in its entirety.

This article was originally published in AC, Jan. 1990. Some images are additional or alternate.

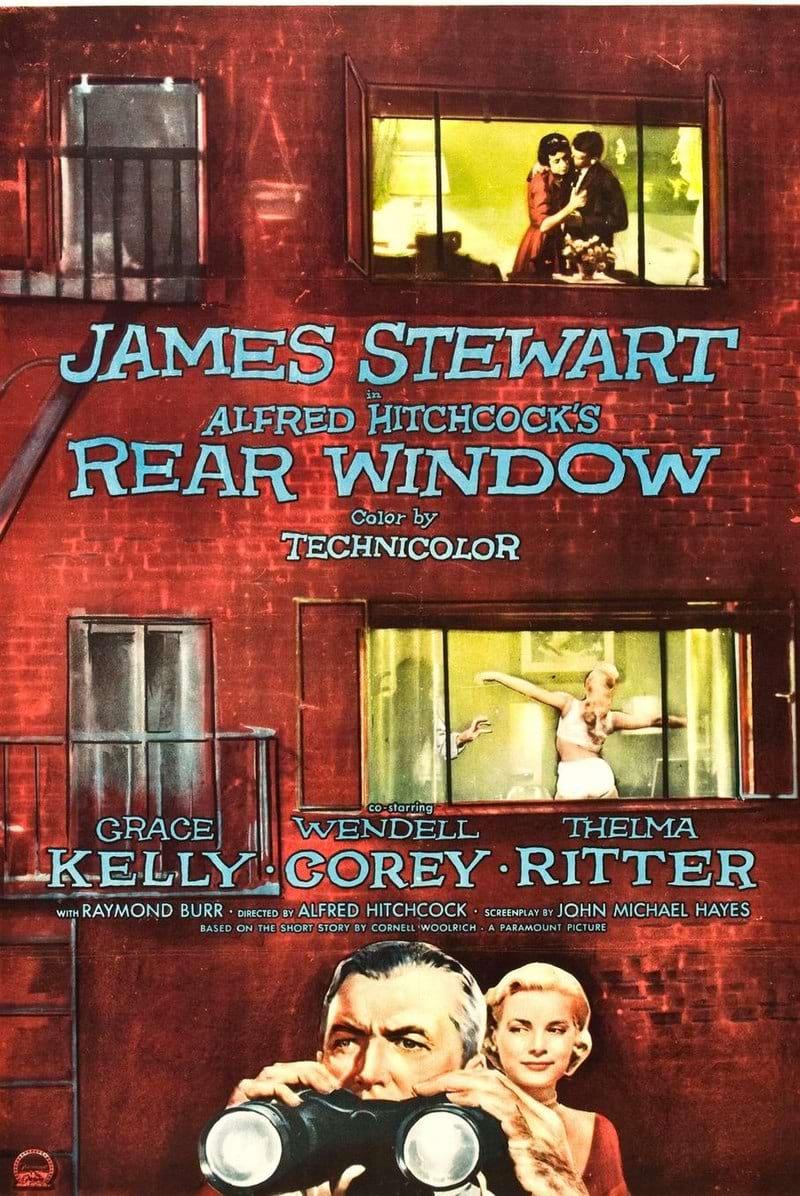

Alfred Hitchcock’s 1954 suspense thriller Rear Window is one of the director's most masterful and enduring motion pictures. Indeed, its endurance is well illustrated by the fact that when the film was re-released theatrically in London in 1983, after being unseen for more than a decade, many British film critics considered it the best film of the year. The film is a visual and aural treat featuring a first-rate cast, and the making of the film presented Hitchcock and his talented production crew with numerous unique challenges.

In the summer of 1953, Lew Wasserman, then Hitchcock's agent at MCA, arranged a deal with Paramount Pictures for the director to make a total of nine films (as it turned out, he only made six). The unusual contract called for the rights of five of these films to revert to Hitchcock eight years after their initial release. Rear Window was the first film that the director made under the Paramount contract and was one of those to which he would even actually own the rights, the others being The Trouble With Harry, The Man Who Knew Too Much (Hitchcock's 1956 remake of his 1934 British production), Vertigo, and Psycho.

Hitchcock had been planning Rear Window during the filming of Dial 'M' For Murder at Warner Brothers. He had acquired the film rights to a 1942 short story by the mystery author Cornell Woolrich under the pseudonym William Irish. The story concerned an invalid confined to his room who spies on his neighbors and witnesses a murder. Eventually, the killer attempts to shoot the invalid from across the yard. However, the invalid manages to protect himself at the last minute by grabbing a bust of Beethoven and using it as a shield.

At the suggestion of his agents at MCA, Hitchcock hired a scriptwriter in his mid-30's named John Michael Hayes to write the treatment and script. Hayes, who received a fee of $15,000 for his services on the film, had a background of comedy and suspense writing for radio, and he turned out to be a perfect complement to Hitchcock with his ability to provide strong, credible characterization and witty, sophisticated dialogue. Hayes would subsequently be scriptwriter for Hitchcock's next three pictures — To Catch A Thief, The Trouble With Harry, and The Man Who Knew Too Much.

Hayes' first task, which he apparently undertook with great skill, was to draft the treatment for Rear Window. It was on the basis of this treatment alone that James Stewart accepted the picture's starring role and agreed to forego a salary and receive instead a percentage of the film's profit.

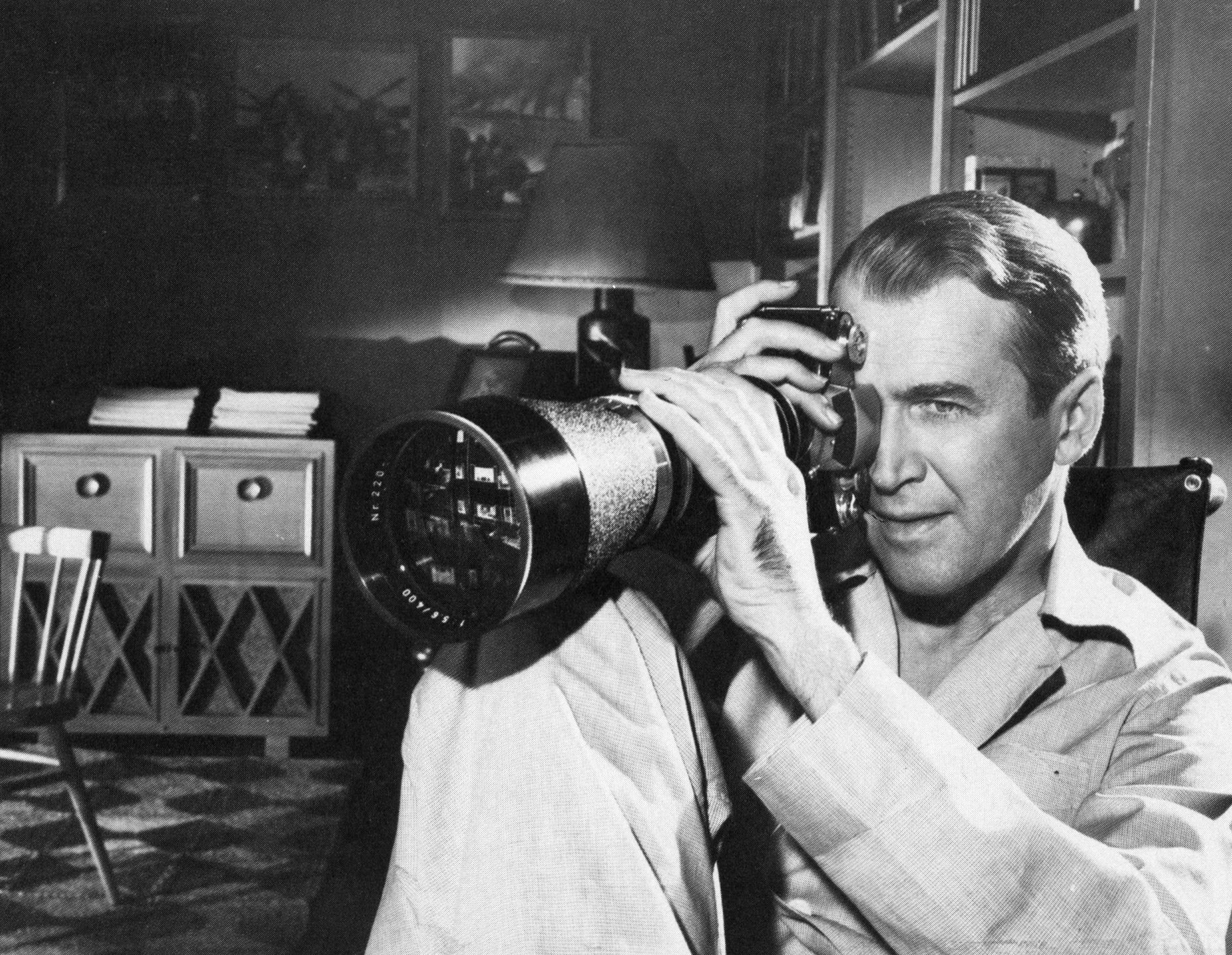

Following the completion of the treatment, Hayes proceeded to work on the screenplay. The story as filmed concerns a magazine photographer, L.B. "Jeff" Jeffries, who broke his left leg in on-the-job accident and is confined to a wheelchair in his Greenwich Village apartment. The large window at the rear of his apartment overlooks a courtyard surrounded by numerous other apartments and, to while away his time, he starts spying on his neighbors. Gradually, he suspects that one of them, a jewelry salesman named Lars Thorwald, has murdered his invalid wife, dismembered her body, and scattered her remains around the city.

Jeff relates his suspicions to his sophisticated girlfriend, Lisa Carol Fremont, who eventually believes him. Together they try to convince Jeff's wartime buddy, Thomas J. Doyle, who is now a New York City detective, that a crime has been committed — but he is extremely skeptical. Eventually, Jeff's suspicions are confirmed, and the film climaxes as Thorwald, after discovering that he is being watched, enters Jeff's apartment and, in the ensuing struggle, pushes Jeff out of the window onto the courtyard below. As a result, Jeff breaks his other leg and winds up again confined to his apartment, only this time with both his legs in plaster.

James Stewart played Jeff, his second role in a Hitchcock picture, his first having been in Rope, made five years earlier at Warner Brothers. Stewart would star in two subsequent Hitchcock films, The Man Who Knew Too Much and Vertigo, a film considered by many Hitchcock aficionados to be the director's ultimate masterpiece.

For the role of Lisa Fremont, Hitchcock chose Grace Kelly, who had starred in his previous picture, Dial 'M' For Murder. While making that film, Hitchcock had discussed Rear Window with Grace Kelly but had made no mention of the actress starring in it. She was, therefore, somewhat surprised when, in October 1953 while in New York, she received a call informing her that Hitchcock was expecting her in Los Angeles for wardrobe fittings for Rear Window. However, Miss Kelly had just been offered the leading role opposite Marlon Brando in Elia Kazan's On The Waterfront, which was to be shot in New York and was better suited to her plans. Nevertheless, the role of Lisa in Rear Window appealed to her, as did the opportunity of working with Hitchcock again, so she quickly decided to accept the part. (Eva Marie Saint eventually took Grace Kelly's role in On The Waterfront and won an Academy Award for best actress.)

Casting of the film was completed by November 1953. The role of Lars Thorwald, the murderer-salesman, was assigned to Raymond Burr, and that of Doyle, the detective, to Wendell Corey. Thelma Ritter took the role of Stella, the witty, worldly insurance company nurse. Other cast members of note included Kathryn Grandstaff who, as Kathryn Grant, would later become the wife of Bing Crosby, and Ross Bagdasarian (in the role of a struggling composer) who, as David Seville, would become popular through the success of Alvin and the Chipmunks.

With the filming of Rear Window, assistant director Herbert Coleman commenced his successful and creative association with Hitchcock. Ray Milland had introduced Coleman to Hitchcock during the filming of Dial 'M' For Murder. Also joining Hitchcock's regular production crew for the first time was film editor George Tomasini, ACE. In addition, Academy Award-winning costume designer Edith Head renewed her association with Hitchcock after a break of approximately nine years (they had worked together on Notorious in 1945/’46) for what would be the first of a 10-picture collaboration extending over the next 22 years to include Hitchcock's final film, Family Plot.

The director of photography was Robert Burks, ASC, who was already a regular member of Hitchcock's production crew, having worked with the director on all three of his previous films — Strangers On A Train, I Confess, and Dial 'M' for Murder. Burks would go on to win an Academy Award for his stunning Technicolor-VistaVision cinematography for Hitchcock's next production, To Catch A Thief. Burks' camera assistant on Rear Window was Leonard South (current president of the American Society of Cinematographers), who, by 1953, was already a long-serving member of Hitchcock's production crew. South's association with the director had begun back in 1946 with The Paradine Case, and would end in 1976 with his work as director of photography for Family Plot, Hitchcock's last picture.

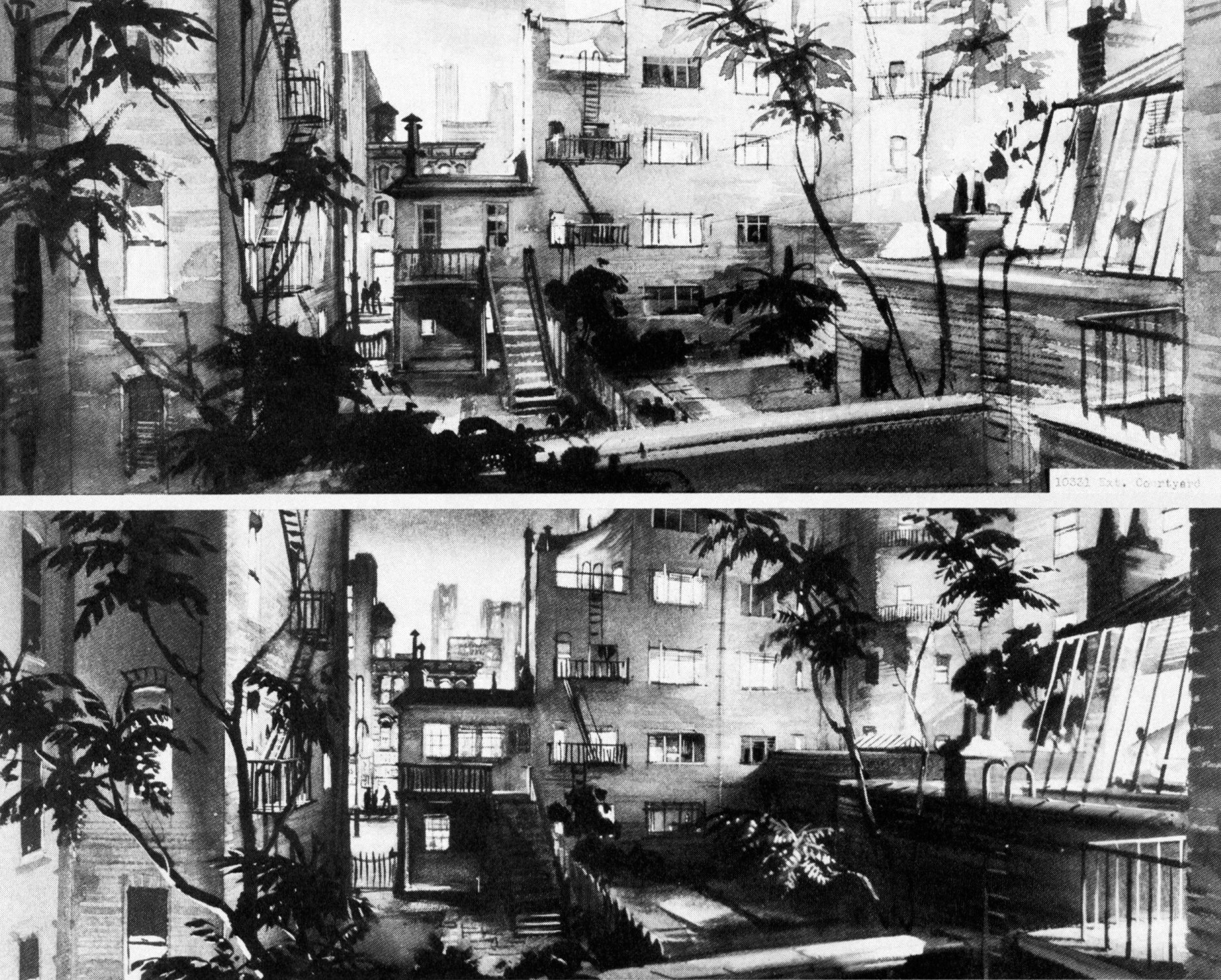

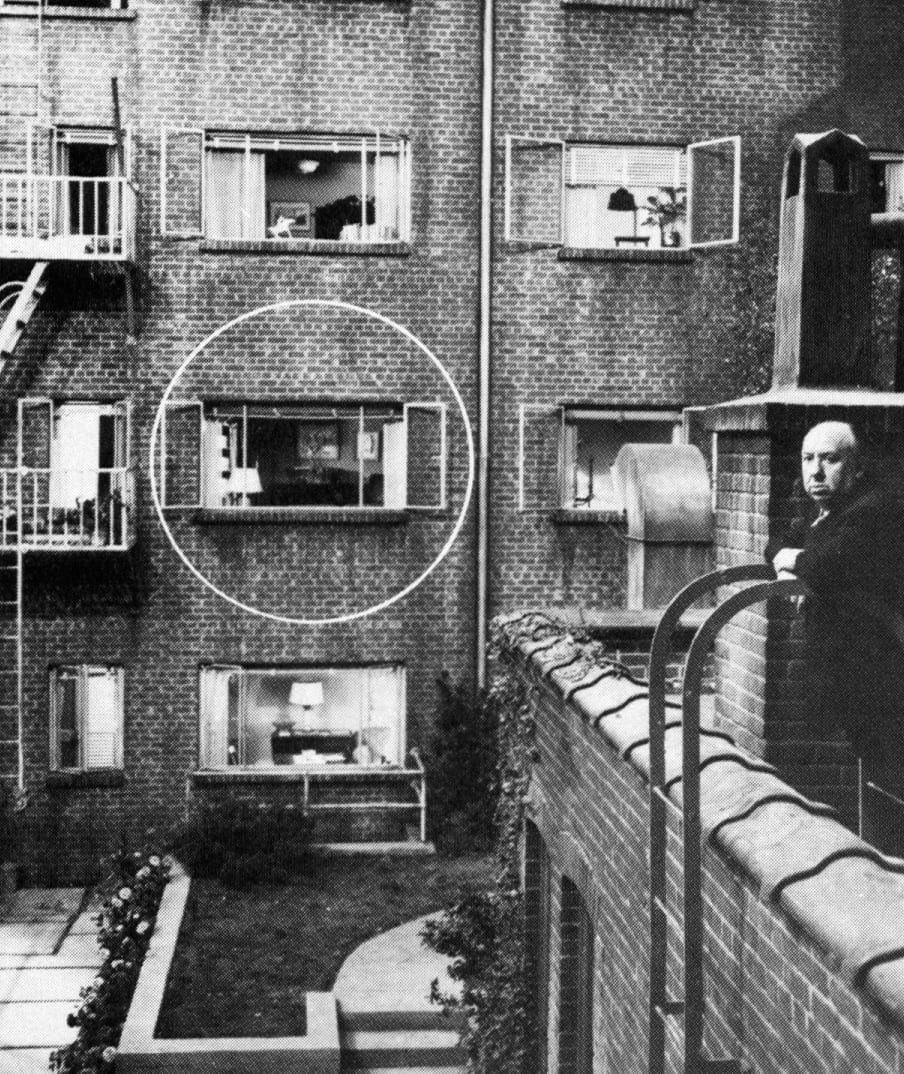

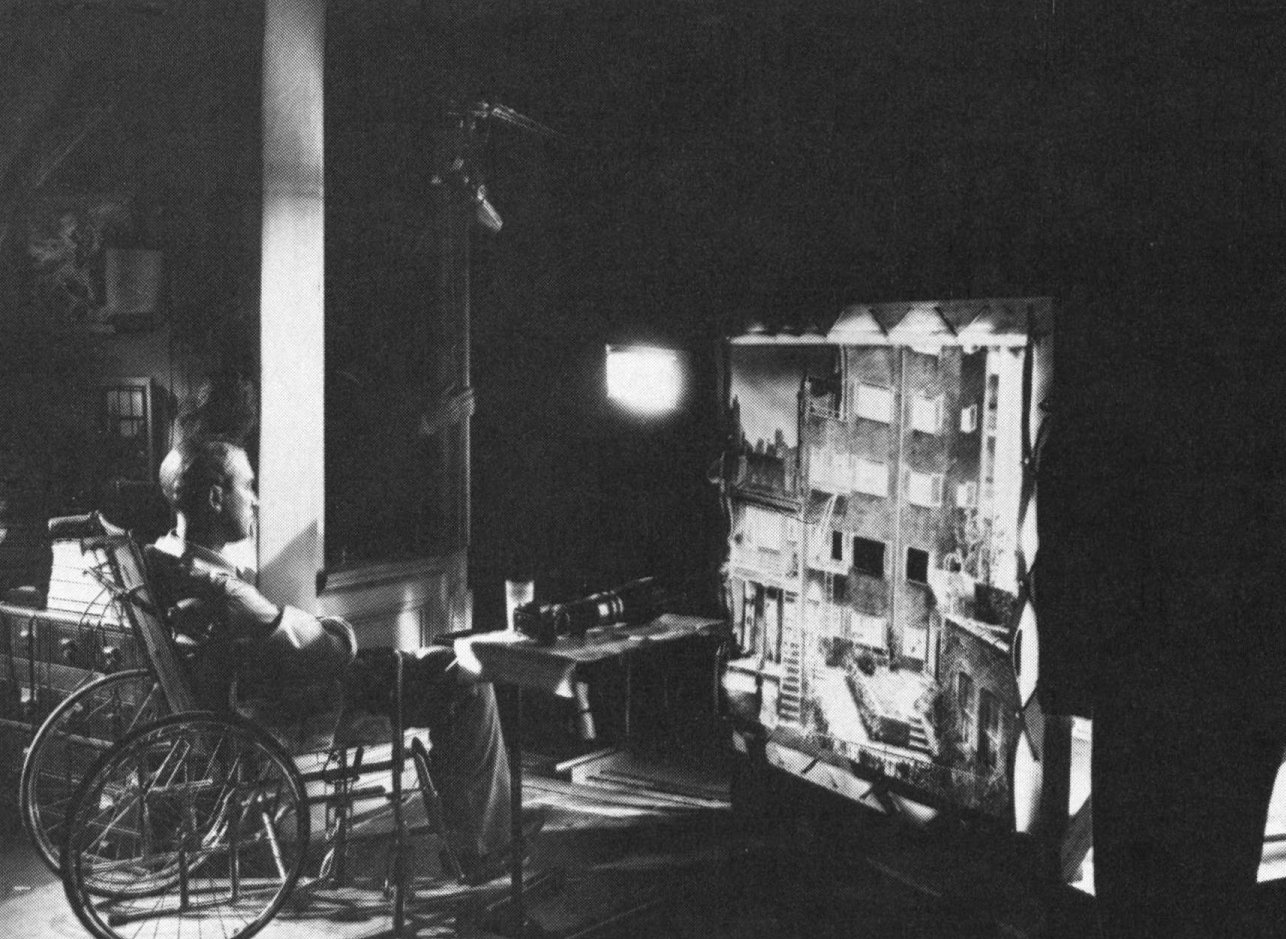

Shooting Rear Window necessitated the design and construction of a gigantic, composite set on which the film was shot in its entirety. Although some of the action takes place in Stewart's apartment, the remaining action occurs in and around the neighboring apartments as seen from Stewart's viewpoint. The enormous set was designed by art director Joseph MacMillan Johnson and built on one of Paramount's largest sound stages, Stage 18 (184'10" x 98'5" x 40'00"). Construction was supervised by Hitchcock himself and took approximately six weeks to complete. This set, one of the largest ever built at Paramount, was very realistic and comprised some 31 apartments, 12 of which were completely furnished. All the apartments surrounded a multilevel courtyard approximately 70 feet wide, and some of the apartment buildings were almost five stories high. The set also included a Manhattan skyline, gardens, trees, fire escapes, smoking chimneys, and an alley leading to a street complete with a bar, pedestrians, and moving traffic. The lower levels of the courtyard were built below stage-floor level while the walls of Stewart's apartment were wild and could be moved to accommodate various camera angles.

“We pre-lit every one of the 31 apartments for both day and night, as well as lighting the exterior of the courtyard for the dual-type illumination required.”

— Robert Burks, ASC

The film was shot on Eastman Color negative and framed for exhibition in Paramount's non-anamorphic "cropped" widescreen process at an aspect ratio of 1.66 to 1.

Read More on Hitchcock:

Hitchcock Talks Lights, Camera, Action

Hitchcock's Rope — Something Different

Revisiting Hitchcock's Vertigo

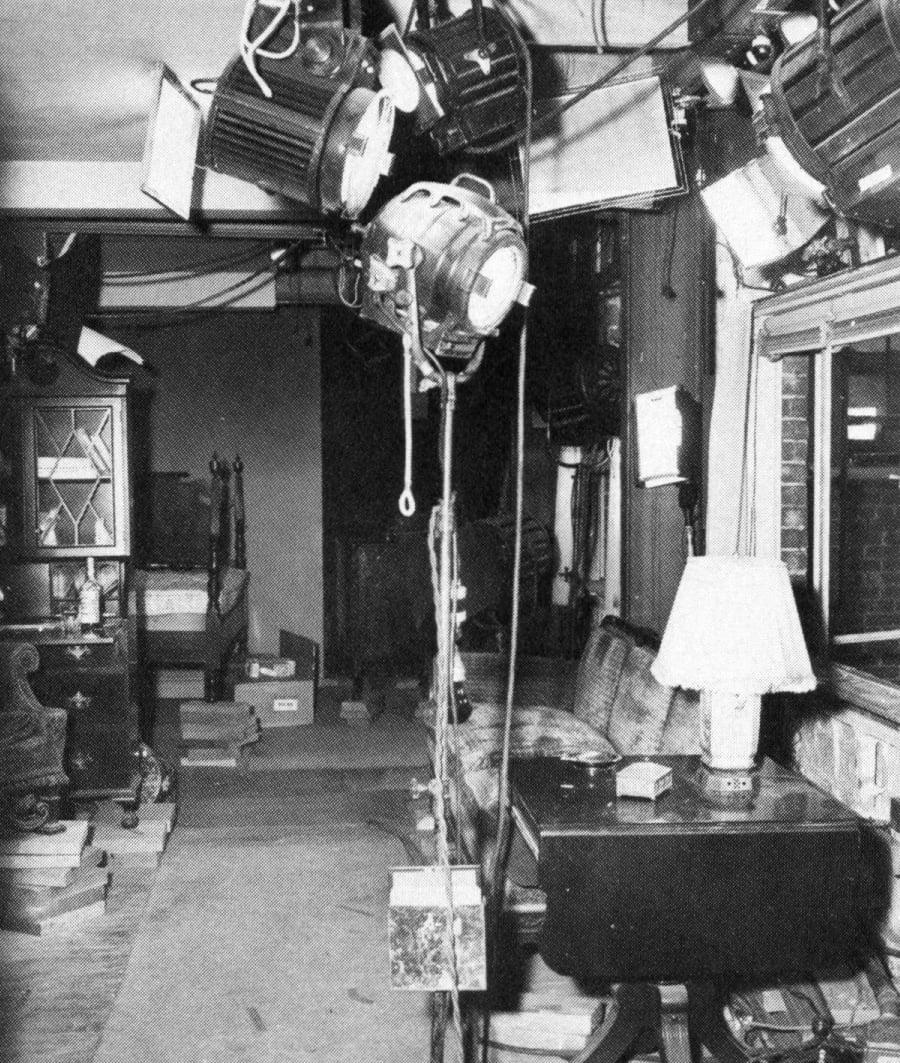

The technical challenges provided by the filming of Rear Window were formidable and stemmed mainly from the requirement for virtually all shots of activity in and across the courtyard to depict the scene as observed by Stewart either with the naked eye or with the aid of binoculars or a telephoto camera lens. The majority of these shots were required to pinpoint small objects and/or convey, without the aid of dialogue, important action taking place at distances varying from 40 to 80 feet from Stewart's apartment. In addition, the set had 70 openings (windows, doors etc.), while each apartment seen from Stewart's window had to be lit as if it was a separate set rather than merely for effect. Moreover, the entire set was required to be lit for both day and night settings.

It goes without saying that the rigging and illumination of this complex set was an enormous challenge in itself and, at the time, was the biggest electrical job ever undertaken at Paramount; at one point, almost every piece of lighting equipment on the lot was in use on the set. Indeed, at the commencement of filming, the heat generated by the many lighting units was intense enough to activate the sound stage's automatic sprinkling system, which had to be disconnected to permit filming to continue.

Because of the size of the lighting project, the decision was made to pre-light the entire set, as lighting it in the conventional manner would have required more than 100 days of shooting. As Burks told American Cinematographer (February 1954): "I went on the sound stage about 10 days prior to the starting date. Using a skeleton crew, we pre-lit every one of the 31 apartments for both day and night, as well as lighting the exterior of the courtyard for the dual-type illumination required. A remote switch controlled the lights in each apartment. On the stage, we had a switching set-up that looked like the console of the biggest organ ever made!"

Following the pre-lighting phase, a large chart was prepared which detailed the set-lighting plan and indicated which switches needed to be activated for a given lighting scheme. While adjustments to the lighting were continually necessary in order to fit certain action, the pre-lighting project overall saved an enormous amount of time during shooting, with the change of set lighting from night to day, for example, being accomplished in about 45 minutes.

A major challenge for Burks with respect to the set lighting was the need to film action taking place in the various apartments during the day in such a way that the apartment lighting appeared as natural as possible. Earlier attempts to achieve this were unsuccessful in that the apartments looked as if they were lit as at night, resembling shop windows. Therefore, Burks had to achieve a lighting balance which avoided the "shop window" look while providing sufficient light for action inside the apartments to be visible from across the courtyard.

An additional problem associated with the daytime apartment illumination was the need to maintain the required light intensity at the same level regardless of the positioning of the actor in the apartment. To prevent any actor from being "burnt up" by the courtyard daytime lighting as he or she approached the apartment window, Burks placed graduated scrims below the lighting units which gradually diffused the apartment lighting as the actor walked towards the window.

The greatest technical challenge during the actual shooting was to film the action across the courtyard in such a way that the resulting image matched exactly what Stewart observed with the aid of a reflex camera fitted with a telephoto lens. These subjective shots demanded good definition combined with adequate depth of field. A typical scene where these requirements were of paramount importance was a key one in which the murderer salesman is seen by Stewart to remove a wedding ring from his wife's purse. Burks' challenge was to clearly show that the object being removed was a wedding ring as observed by Stewart from about 70 feet away. Initially, Burks had the camera situated in Stewart's apartment and fitted with a powerful 10-inch telephoto lens. In order to stop down the lens to gain definition and depth of field, he also used a high level of set illumination (1,600-foot candles), the exposure setting being f/5.6. However, the definition obtained under these conditions was inadequate to clearly show that the object in question was a wedding ring. Eventually, Burks was able to successfully shoot this and similar scenes by moving the camera out on a boom overhanging the courtyard and by using a six-inch lens with the exposure set at f/5.6

Having solved the problem of adequate definition on such shots, Burks still had to contend with an extremely narrow depth of field which required changes of focus even if an actor moved half a step backward or forwards. Therefore, shooting distances had to be precisely determined but, because of the large distances involved, the traditional method of running a tape measure from the camera to the point of action just prior to shooting was impractical. Burks overcame this problem by pre-measuring these shooting distances at the same time the set pre-lighting operation was being undertaken. This process was followed by the preparation of a comprehensive chart of distances and focusing information. Thus, for any given shot, a glance at the chart provided the exact distance from the camera to the point of action.

For scenes representing Stewart's naked eye point-of-view, Burks used a 2-inch lens with the camera situated in Stewart's apartment. To provide variety, Burks used a 3-inch lens on cut-back shots of the same scene.

One of the most famous sequences in Rear Window is the long, expositionary shot near the beginning of the film which Hitchcock uses, by purely cinematic means, to introduce the viewing audience to Stewart's neighborhood and to inform the viewer that Stewart is a photographer who has broken his leg while on a photographic assignment. The uninterrupted portion of this sequence, which lasts almost 90 seconds, commences with the camera trained on a couple opposite who, because of a heatwave, have chosen to sleep on the fire escape and can now be seen in the process of awakening at the start of a new day. The camera then pans left to the apartment of a dancer who can be seen getting dressed, then left again to reveal the alley leading to the street where a water tanker is spraying the pavement. The camera then starts to pull back until it eventually enters, via the window, Stewart's apartment. There, in closeup, Stewart can be seen sleeping in his wheelchair. The name of Stewart's character is then identified via a close-up of the inscription "Here lie the broken bones of L.B. Jeffries" on the plaster cast on his left leg. The camera then tracks back further to reveal more of Stewart's apartment, then pans left to show in turn a smashed camera; a photograph of a motor speedway accident in which a wheel of one of the involved cars can be seen hurtling towards the camera; and an array of equipment that one might expect to find in a photographer's apartment.

To film this complicated sequence, Burks had to mount the camera on the biggest boom available on the Paramount lot, which was fitted with an extension. The shot required extensive planning and many rehearsals and involved numerous focus changes. It took ten takes and half a day of shooting time to execute the shot to Burks' satisfaction.

The special effects for Rear Window were performed under the guidance of Paramount's expert in his field, John P. Fulton, ASC. Most of these effects were filmed, whenever possible, on the set. One such effect was required for a sequence in which Stewart compares the actual scene of a certain flowerbed in the courtyard with the same scene depicted in a 35mm transparency taken earlier, the latter being viewed by means of a hand-held slide viewer. The filming of this illusion involved the attachment to the camera of a customized device consisting of prisms and a short-range projection set-up and necessitated quick changes of focus. Irmin Roberts, ASC, made the special shots.

In many scenes in the film, the courtyard and apartments opposite Stewart's apartment can be seen reflected in the lenses of his binoculars and reflex camera. The successful filming of these reflections demanded precise control of their intensity relative to that of the ambient light. This was accomplished by placing out of camera range a few feet in front of Stewart an enlarged, rear-lit transparency of the courtyard and apartments, the reflection of which simulated the reflection of the real scene.

One of the sequences in the film depicts a heavy rainstorm that occurs during the night. This rain effect was accomplished through the use of special effect "rain birds" situated above the set and necessitated the installation of a complete drainage system to prevent flooding of the set and sound stage. In the climactic sequence of the film, the murderer-salesman enters Stewart's apartment and, after a violent struggle, succeeds in pushing Stewart out of the window onto the hard courtyard some 30 feet below. Stewart's fall was filmed directly from above using the traveling matte technique to create the illusion of the actor falling to a certain injury on the concrete below. This special effect involved filming Stewart falling onto some mattresses and then matting in this shot with one of the backgrounds that had been photographed separately minus the falling actor.

The music score for Rear Window was composed by another of Hitchcock's earlier collaborators, Franz Waxman (he had provided the score and Bill Schurr for Hitchcock's first American feature film, Rebecca, between takes. as well as the scores for Suspicion and The Paradine Case). The score is unusual in that very little of it is heard as background, off-screen original music but rather as familiar "on-scene" music which emanates from the various apartments surrounding the courtyard. This music includes several popular songs such as "That's Amore," "To See You Is To Love You," and "Mona Lisa," as well as some more serious musical selections such as an extract from Leonard Bernstein's "Fancy Free," the aria "Ach so fromm" from Flotow's opera "Martha," the famous "Carnival of Venice," and an excerpt from Schubert's ballet music for the play "Rosamunde."

The score's main interest, however, is provided by an original song which, throughout the film, can be heard being composed by the struggling songwriter in the studio apartment overlooking the courtyard. Eventually, in the final scene of the film, it is played in full orchestral form on a gramophone recording, having by then acquired the title "Lisa" in honor of Grace Kelly's character for her role in bringing the murderer-salesman to justice.

Principal photography was completed in January 1954, the film's overall budget being about $1 million. The world premiere was held at New York's Rivoli Theater on August 4, 1954, with the Los Angeles premiere following approximately two weeks later, on August 16. The film was a resounding critical and commercial success and by May 1956 had grossed $10 million. David O. Selznick, the producer who, in 1939, brought Hitchcock to Hollywood from England, called the film "a brilliant display of motion picture craftsmanship."

Rear Window received four Academy Award nominations — for direction, screenwriting, color cinematography, and sound recording — but, unfortunately, failed to win in any of these categories. However, Grace Kelly won awards in the Best Actress category from both the National Board of Review and the New York Film Critics for her role in the film, while scenarist John Michael Hayes won the Edgar Award for best mystery writing for a Film.

Shortly following its theatrical re-release in 1968, Rear Window was withdrawn from circulation and remained unavailable for public viewing until its second re-release in the fall of 1983. The reason for the film's withdrawal appears to have been the initiation of a legal dispute by the estate of Cornell Woolrich, the author of the short story on which the film, albeit somewhat remotely, was based. According to John Russell Taylor, Hitchcock's authorized biographer, a legal firm that owned copyright in Woolrich's works filed a lawsuit following the author's death, and succeeded in preventing the film from being screened until Woolrich's estate was settled. Regardless of the reason for the film's mysterious disappearance, it is now, fortunately, widely available for both public and home viewing, and is being enjoyed and appreciated by a new generation of filmgoers.

This in-depth interview with Hitchcock details his approach to using the camera and collaborating with his cinematographers on various projects.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.