Hollywood Babylon

Linus Sandgren, ASC, FSF helps Damien Chazelle capture an industry’s bawdy beginnings.

The meek rise to power, the mighty fall from grace, and everyone struggles with the seismic change known as “talkies” in Babylon, which explores the wild side of early Hollywood. There’s Manny Torres (Diego Calva), a young immigrant who arrives in L.A. with filmmaking aspirations and falls in love with free-spirited aspiring actor Nellie LaRoy (Margot Robbie); box-office star Jack Conrad (Brad Pitt), whose career is on the verge of ruin; and struggling Black musician Sidney Palmer (Jovan Adepo), who helps usher in an era in which jazz artists are billed as screen stars.

Babylon is the third feature collaboration between cinematographer Linus Sandgren, ASC, FSF and director Damien Chazelle. As they had on La La Land (AC Jan. ’17) and First Man (AC Nov. ’18), the duo chose to shoot their latest project on 35mm film. The filmmakers also “elected to go with the anamorphic format,” Sandgren says, “as it felt like the right way to tell an epic story about Hollywood. Damien really wanted to see that whole world, and it had to be a wide ’Scope film.”

Getting the Party Started

Babylon tells “a crazy story,” the cinematographer notes. “Damien found inspiration from the absurd humor in this tale, and we wanted the camera to be in the absurdity, moving among the ludicrous events. Everything I did was intended to be expressive to fit the roller coaster of events, as well as the dramatic contrasts and turns in the characters’ lives. I aimed for a look that was contrasty and harsher, pushing the image on the negative and with the lenses and the exposures — much more than I would ever do on another film.

The lunacy is on display from the beginning of the film, when Torres is tasked with moving an elephant up a steep road so it can appear at an extravagant soirée. The party scene was filmed in the Ace Hotel in downtown L.A., a historic structure that includes a movie theater. “We kept the camera curious,” Sandgren says. “We didn’t want to cut; we wanted to see the environment, racking and panning around after blocking the scenes in as few shots as possible. That was incredibly difficult, as everyone had to be in precise positions as the camera passed. Most of the extras were dancers, though, which helped us to be precise with the timing.

“Damien and I loved the look of the hotel and lobby, but it was a very tight space,” the cinematographer continues. “We had to do a bit of creative thinking to make it work. We ended up using a Spydercam to start the sequence, pulling back through the 200-person crowd at the party, flying up high, and then flying back into a close-up of Sidney playing trumpet in the band, and into a whip pan. From the whip pan, we stitch to a Steadicam shot [operated by Brian Freesh] that moves through the party. Brian is really solid and has a great musical sensitivity — which, in most of the scenes in Babylon, is crucial. We also made copious use of the Chapman Miniscope 7, which we often used instead of a dolly. It’s quick, narrow and fits through doors — a great tool. We actually used it daily throughout the shoot.”

Sandgren operated the A camera, and Davon Slininger operated B camera and served as splinter-unit cinematographer. Sandgren notes that he worked with Slininger on Babylon in the same way they did on First Man. “We pretty much shot one camera most of the time, but there are some scenes where we’d bring in a second camera,” Sandgren says.

“When it’s just me operating, Davon is off shooting additional shots of things like a projectionist loading film while smoking, or celluloid being tinted — many of the inserts you see throughout the movie,” the cinematographer says of their work on Babylon. “He did really great things on this movie.”

Jorge Sánchez, Sandgren’s longtime 1st AC, was also onboard, as were chief lighting technician Tony Bryan, key grip Anthony Cady and dolly grip Michael Wahl.

Single Take at Dawn

With help from Torres, LaRoy cons her way into the private party, and the two take a wild ride together. As dawn breaks, she leaves the party, triumphant after her adventurous night. “She walks out into the dawn, and we’re in a single take from that moment,” Sandgren says. “We see Manny step out into a close-up and then move around his shoulder as he watches her dance around at the break of dawn; we follow Manny to a two-shot with Nellie and she leaves frame for a close-up of Manny; and then we pan to Nellie, who gets into her car and drives off. The camera pans around and pushes into Manny’s face again, and the character Jimmy [Cutty Cuthbert] comes into the background and yells for him to come back inside.

“It felt beautiful and emotionally intimate to not cut, and to just stay with him in that moment on a oner,” Sandgren continues. “It’s subtle, but it was complicated to do; we had to do it off a Scorpio 45 telescopic crane, operated by Bogdan Iofciulescu, just minutes before the sun was rising, and we only had a few minutes of the right light. As with all low light scenes, I shot it at T2, and it’s a really shallow depth of field — which was a great challenge for Jorge, but lucky for us, he is a really masterful focus puller. On La La Land, we would take a whole day to rehearse shots like that, but on this production, we had so many shots like this, and a tight schedule, so we had to spend most of our time shooting.

The production filmed on practical locations in and around L.A., at sites that included a former residence of William Randolph Hearst, Lake Piru, outside Paramount Pictures in Hollywood, inside and outside Paramount stages, and on Paramount’s New York Backlot. “We didn’t really do that much onstage, apart from the scenes in the movie that took place on stages,” recalls Sandgren. “Damien wanted to see the real Los Angeles, using real locations. And scenes set at the silent movie studio Kinoscope were built on location in a valley in Piru, to look more like L.A. in the ’20s.”

Hollywood, Wide Open

“We shot in traditional Academy anamorphic, which is offset to one side to accommodate the soundtrack that would be added later,” Sandgren says. ”We did a 4K scan and a digital intermediate with a full variety of theatrical release formats, including 35mm anamorphic film prints and 70mm spherical film prints, as well as digital formats in Imax, Dolby Vision and 4K DCP.”

Camtec Motion Picture Cameras in Burbank, Calif., provided Arricam LTs for the production, and Sandgren teamed them with Atlas Orion anamorphic lenses. “I had the Orions on Don’t Look Up, and I was really happy with them,” he says. “Technically, they’re great — they have a really close focus and they don’t go out-of-focus at the edges — and in fact I embraced it, and shot all night scenes at wide open. They’re all a T2, which is amazing. Wide open, they have a slight color aberration, but it’s not excessive. We had Atlas custom-tune them because we didn’t want the film to look too polished; we wanted to embrace the dirt and filth in the world of Babylon. I worked with [Atlas Co.’s president and lead designer,] Forrest Schultz, who tweaked the lenses to maintain their sharpness but add more blooming in the highlights. He did this by hand-polishing certain elements to give them a slightly scratched surface that spread the highlights beautifully. It gave us a series that was just a bit more expressive, to match the attitude Damien and I were trying to convey.” (See details below.)

Playing It Rough

Sandgren further “roughened up” the image by push-processing all of the footage 1 stop, rating each stock an additional 1 stop over, and then going “really aggressive with my exposure, especially in daylight, allowing things to go as much as 4 stops over in exteriors to show the heat of L.A.” The push process was completed at FotoKem’s facility in Burbank.

“Something fascinating happens with film in the development process,” he continues. “I find that the mids come out first, and then the highlights and blacks are developed. If you develop in the time that Kodak says you should, then the mids have developed and the blacks and highlights come along. But if you keep developing, the mids stay where they are and the blacks and highlights keep developing, pushing more contrast as they build on the negative and the highlights start to bleed a bit into the mids. If you pull one stop, the mids develop, but the blacks and highlights underdevelop, leading to less contrast. For me, this has always been a great tool — in addition to lens choices and lighting, when I am creating the looks for my projects. It is a way to further connect the visuals to the emotions in the story in an impressionistic way.”

Sandgren’s strategy involved four Kodak Vision3 negatives: 50D 5203 (pushed 1 stop and rated at 25 ISO) for day exteriors, 250D 5207 (pushed 1 stop and rated at 125 ISO) for day interiors, 200T 5213 (pushed 1 stop and rated at 100 ISO) for most night scenes, and 500T 5219 (pushed 1 stop and rated at 250 ISO) for select night sequences. “200T was my first choice for night work because it has a bit more contrast than the 500T,” Sandgren says. “I liked that, but there were so many really dark scenes that I just couldn’t use it all the time.”

Silent Period

Babylon also features black-and-white sequences — ostensibly footage shot by period cameras — that Sandgren shot on Eastman Double-X 5222 with Arriflex/Zeiss Super Speed “B-Speed” spherical lenses and a Super 35 camera. In one example, LaRoy wows her colleagues with her big-screen debut, dancing in a saloon scene. The “period” film footage was shot with Arriflex 435 cameras and the B-Speeds. The camera was connected to a remote-control unit that allowed Sandgren to mimic a hand-cranked look by manually moving the frame rate between 18 fps and 22 fps. “We also shot some clips in the film on the 2709 Bell & Howell cameras, as well as other early 1900s silent-film cameras, and I was surprised to see how phenomenal those cameras were — pin-registered and incredibly solid!” Sandgren marvels.

In another scene that incorporates black-and-white, we see Conrad in action onscreen, arriving on a mountaintop amid a fierce battle — to achieve his romantic goal and kiss the girl. To precisely intercut their color production footage with the black-and-white footage, the filmmakers utilized a beamsplitter 3D rig. “Brad [Pitt] is on the mountaintop, and there’s a huge battle with 700 extras happening below,” Sandgren explains. “We push in to this kiss, and we wanted to shoot anamorphic color and spherical black-and-white at the same time, from the same perspective. So, in the 3D rig, we had the 435 on top and an LT on the bottom. This scene was really what made us decide to use the 435 instead of an old period camera for the main silent-movie footage — since hand-cranking an old camera was destabilizing the rig, and focus pulling on those old, small lenses was quite a challenge.

Naturalistic Light, Rattlesnake Fight

“I was a bit reckless with my exposures, but I would light as naturalistically as I could,” Sandgren says of his approach. “I had an impressionistic mindset. I did use hard light a bit more than I might normally, but I tried to light with windows and practicals and keep it natural; if the window was overexposed, I let it be and didn’t add any fill. I embraced those problems rather than correcting them. I used a lot of 20K tungstens or Maxi Brutes for late-afternoon sun. I augmented natural light a bit with LEDs.”

This naturalistic approach was taken to an extreme for a night scene in the desert. When LaRoy’s deadbeat father (played by Eric Roberts) brags about fighting a snake, she challenges him to do it again, and the partygoers travel to the desert at night to find a rattlesnake for him to battle. The scene is lit primarily with the surrounding cars’ headlights, lamps to provide a bit more exposure. “I added a condor holding a large, soft, silk moonlight, at 3 stops under, but the main light for the scene was provided by the headlamps, which were more like narrow beam headlights,” says Sandgren. “Looking at the people backlit was flare-y and when we were looking out into the desert from the cars, everything was front lit, but we embraced that. I didn’t mind it feeling a little flat [because] it felt real. Out at the action, near the snake, I was reading about a 2, which meant that everyone closer to the cars was a lot brighter, but I let that go. It was part of the messiness!”

Tinseltown’s True Colors

Sandgren worked with Company 3 colorist Matt Wallach on the dailies and the final grade. “For me, so much is set in the dailies — they’re so important — that I want the same colorist working on my dailies and my final grade,” says the cinematographer. “Since Joy [2015], I have worked with Matt on almost all of my productions, and when we did No Time to Die, we moved on to have him also do the DI and trailers. It makes so much sense to me, as we’re establishing the look in the dailies and doing most of the work there, and then just finessing in the final grade. Matt works primarily from printer lights and primaries, and he sends me stills I can review on my calibrated iPad on set, and then I show those to Damien. When we’re happy, that’s the look, and we don’t change it. I don’t want to wait six months or a year to get the final look. I want the director working with it all along, I want the producers seeing it all along, and I want the test screenings and the trailer to have the final look. With this approach, the DI goes a lot faster, because we’re merely polishing and finishing. Matt starts with the ASC CDL from the dailies grade, and we can do cosmetic adjustments from there.”

Bespoke Optics

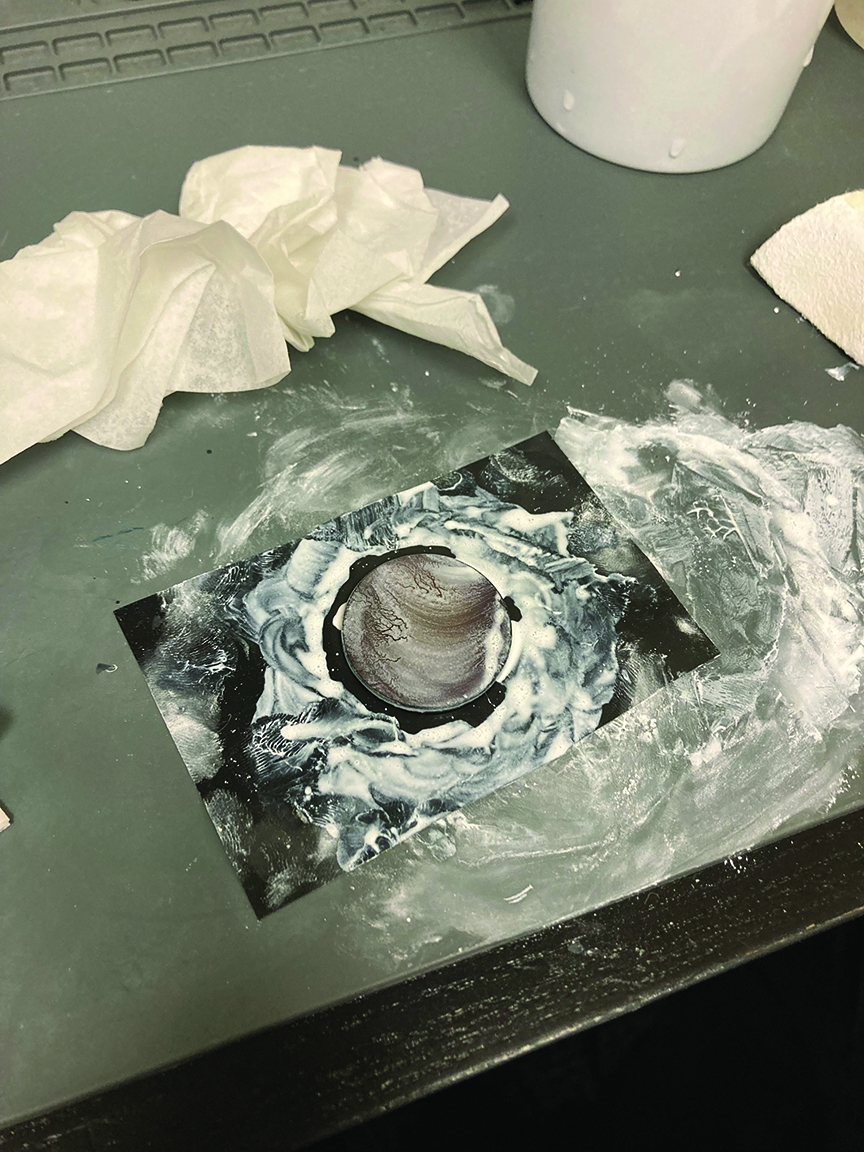

To customize Orion anamorphics for Sandgren, Atlas Lens Co. president and lead designer Forrest Schultz says he “tried to replicate the messed-up surfacing that a lot of older optics get through years of cleaning, scratches, fungi, etc. I applied some micro-scratching into the coating, not entirely taking it off. I isolated a single element from the design and de-polished the surface of the element by hand, using cerium-oxide slurry and steel wool.

“Each Orion received the same treatment, although the amount and intensity of the de-polish varied so that the effect would be equally pronounced on each focal length,” he continues. “The effect was very subtle — when you’d look at the element by eye, you wouldn’t really see it. On camera, however, it was immediately apparent. The lens would bloom on very strong sources and areas of high contrast, which is why Linus preferred it over a filter on the lens. It seemed to respond dynamically, so pointing at windows of bright sun brought out a natural-looking halation. It didn’t affect the resolution, either — there was no real softening effect.”

Atlas also altered the barrels of the series to differentiate them, polishing off the black anodizing to raw aluminum, which Schultz then brushed on a lathe. With his wife’s help, he then repainted the lens engravings by hand.

“Linus and [1st AC] Jorge [Sánchez] would frequently visit so we could A/B the look and dial in the exact strength of the effect Linus wanted,” Schultz notes. “I really enjoyed the process, and it was fun to see Linus light up when we got the look right!” — Jay Holben

Following the publication of this story, Sandgren sat down with Shelly Johnson, ASC to discuss his camerawork in an episode of ASC Clubhouse Conversations:

2.39:1

Cameras | Arricam LT, Arriflex 435, Bell & Howell 2709

Lenses | Atlas Orion, Cooke Anamorphic/i zoom, Arriflex/Zeiss Super Speed “B-Speed”

Film Stocks | Kodak Vision3 50D 5203, 250D 5207, 500T 5219, 200T 5213; Eastman Double-X 5222