Paging 007 for The World is Not Enough

Cinematographer Adrian Biddle, BSC helps director Michael Apted modernize James Bond.

Unit photography by Keith Hamshere and Jay Maidment

Even seemingly tireless British secret agent James Bond could use some rejuvenation after 18 big-screen adventures, so on “Bond 19” (as The World is Not Enough was referred to during its production), producers Michael G. Wilson and Barbara Broccoli made a rather surprising directorial choice. “I thought they were joking,” admits a laughing Michael Apted, recounting the meeting in which he was offered the reins of the new 007 picture. “When it became clear that they were looking for something a little bit different — that they wanted to beef up the drama a bit and get the stuff between the action scenes in better shape — the choice began to make sense.”

Suitably enough, the plot of The World is Not Enough focuses on the film’s characters. Feeling responsible for the death of a British oil tycoon and friend who perished in a terrorist bombing at MI6 headquarters, Bond (Pierce Brosnan) decides to protect the tycoon’s daughter, Elektra King (Sophie Marceau), against harm. In turn, 007 is threatened by Renard (Robert Carlyle), a psycho whose brain contains a bullet that blocks all physical pain. The super-agent is aided by the lovely Dr. Christmas Jones (Denise Richards) and Russian crime boss Valentin Zukovsky (Robbie Coltrane), as well as his associates on her Majesty’s Secret Service: M (Dame Judi Dench), Q (the veteran Desmond Llewelyn), Miss Moneypenny (Samantha Bond) and R (John Cleese).

Apted’s filmography is quite diverse and includes both award-winning documentaries (including Seven Up and its four continuations) and acclaimed features (Coal Miners Daughter, Gorillas in the Mist, Nell). However, no one would have predicted a James Bond movie in his future. “Women were very important to this Bond film, and I’ve done a lot of work with women,” Apted reasons, “so, from my point of view, it was just a terrific opportunity at my age to start learning all of this new stuff! Fortunately, there were a lot of very good people already in place, and I leaned on them heavily — I wasn’t reinventing my own wheel.”

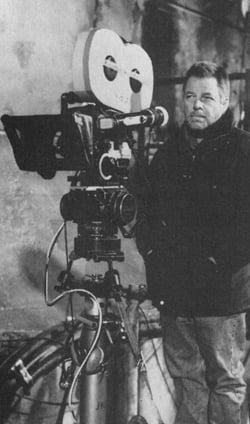

Apted did insist on bringing in his own editor, Jim Clark (with whom he had collaborated on Nell), and a cinematographer he admired but had never worked with before: Adrian Biddle, BSC. The director knew about Biddle from the cameraman’s long association with director Ridley Scott. Biddle began working for Scott in 1970 as a clapper/loader on commercials, and later served as a camera assistant on The Duellists and Alien. He advanced to cinematographer on dozens of commercials and the Scott-directed features Thelma & Louise (which earned the cameraman 1991 Academy and BAFTA Award nominations) and 1492: Conquest of Paradise (see AC Oct. ’92). Biddle’s feature credits also include Aliens, The Princess Bride, Willow, 101 Dalmations, Event Horizon (AC Aug. ’97), The Butcher Boy and the recent remake of The Mummy.

“Adrian was someone whose work I’d liked for a long time,” Apted remarks. “He’d done a lot of work that I thought was very important, and his resume had a lot of range: he had done a huge amount of action work and big-budget stuff, and he had demonstrated a great ability to light women. He seemed to be an ideal choice.

“Michael mostly wanted a mood for each scene, and that’s what I hope I gave him.”

— Adrian Biddle, BSC

“You never know how people will respond to the offer of a Bond film, but I met with Adrian and he seemed really excited by it — I knew he was the guy. He and I spoke the same language, and yet he’d also had experience on these very big-budget films, which I hadn’t. Since I was trying to beef up the drama, the most important thing to me was to work with someone who understood drama and who could effectively photograph actors. Adrian just seemed to cover many bases.”

Interestingly, The World is Not Enough isn’t Biddle’s first Bond film — he had a small hand in the shooting of the action-packed toboggan chase in 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. “I was just a lowly clapper/loader,” the cameraman admits. When Apted called, Biddle couldn’t wait to shoot his very own Bond film. “They’re really historical, aren’t they?” he enthuses, speaking after a long days’ shoot on director Kathryn Bigelow’s upcoming thriller The Weight of Water.

Biddle had his work cut out for him, thanks to Apted’s determination to reinvent the Bond “look,” which invariably involves exotic locales, imposing secret lairs, gripping action and beautiful women.“ I believe that a Bond movie can look as good as any movie on Earth,” Apted states. “We can’t disappoint the fans who are waiting to see what they’re used to seeing, so we still had to deliver the trademarks, but I think there’s a bit more drama in this one than there has been in some of the others. I wanted it to have a richer, more complicated look than a straight-forward action film. I was trying for much more emotion in this film, and I wanted Adrian to reflect that photographically by giving everything a slightly surprising look that wasn’t just flat. Because I was going to take chances with the cast, I wanted him to take chances with the photography, and to reproduce the sort of work he’d done before without falling into the trap of second-guessing what people might want in a Bond movie. We talked about the look a lot, did a lot of scouts, and looked at a lot of action films that we liked, such as The Fugitive, Speed and Die Hard — films that had a lot of great action but still told good stories.”

Biddle counters modestly, “Michael mostly wanted a mood for each scene, and that’s what I hope I gave him, but we didn’t actually set out with a definite look in mind. I really find the look in whatever I’m doing. In this case, it just grew out of the architecture, the sets, the story, and Michael’s ideas. It was very natural. If Bond’s going to make love, then I want that to be a low-key, moody scene. If he’s going into a nuclear facility where the villain is stealing some bombs, that’s also going to look moody, but in a different way than the lovemaking scene.”

The globe-hopping World Is Not Enough production visited a variety of locations that included Charmoix, France; Istanbul, Turkey; Kyle of Lochalsh, Scotland; and Sydney, Australia. This extensive tour provided a few surprises for Biddle. For example, shooting a scene set near the shimmering, silver-walled Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, provided an unexpected turn of events when the traditionally warm, dry Spanish weather suddenly became rainy. Biddle elected to change his plan of attack on the spot. “In the scene, Bond is collecting some money in a building across the way from the Guggenheim, but Michael wanted a great backdrop, so he opted for the museum,” Biddle says. “That was his call, which was really good, but because of the weather, it was a bit of a challenge to get the shots we needed.” The cinematographer had anticipated shooting scenes set near the Guggenheim using short lenses, but switched to longer lenses in order to diminish the depth of field and minimize the appearance of any rain.

Once Bond grabs the money, he takes his leave through a window and begins rappelling down the building’s wall to the street below — until one of the villains makes a desperate grab for Bond’s rope, leaving him hanging precariously halfway down the side of the building. While the action inside the office was filmed on a set at Pinewood Studios using a TransLight backing of the Guggenheim, the stunt itself was shot on location in Spain. “Bond jumps out of the building in a wide shot, which was done by a stunt guy on a bungee rig,” Biddle recalls. “We then built a 30' tower alongside the building and brought Pierce [Brosnan] up there to get some close-ups of him at the halfway point. The bloke upstairs who’s holding the rope lets go and allows it to slide across the floor, which takes Bond the rest of the way down to the pavement.”

Shooting The World is Not Enough in anamorphic, Biddle relied on Golden Panaflex cameras outfitted with C-series lenses, supplied by Panavision London. Asked why he prefers this combination, Biddle replies, “The Panaflex is a really rugged camera, and I like the older lenses. They’re more forgiving, and I think they’re better ‘movie’ lenses. We also carried a [Panavised] Arriflex 435 with us for high-speed work. Although it’s not a sound camera, the Arri has some really good things built into it, like speed-ramping and some other features.”

Biddle used an array of Eastman Kodak film stocks on the film: Vision 500T 5279, Vision 800T 5289, EXR 5248, and EXR 5245. These emulsions were selected for their ability to cover a wide variety of shooting situations. “I like to use Kodak,” the cinematographer remarks. “The range is all there, and I know these stocks so well that I can almost shoot them without a meter. I used the 79 in nearly all of the interiors, the 48 for general exterior stuff, and the 45 — very sparingly — on big, wide daylight exteriors.”

Preferring to have as much “bite” in his negative as possible, Biddle tends to overexpose slightly whenever he can to get the crisp edges and rich blacks that distinguish his edgiest work. “It’s not the amount of light, really, it’s the information on the film,” he says. “I like to print down to get a good thick negative. I do that with all of my stocks, on all of my films, to really help the exposure. I hate to shoot wide-open all the time — anyone can do that. I’m not a big believer in a completely open aperture. I like to give the focus puller and the lenses a chance to be their best. I liked to build up the exposure a little bit and bring out the quality of the lenses by shooting at about T4.5 or 5.6. I’d do it all the time if I could.

“I also think Kodak tends to overrate the sensitivity of their stocks — except maybe the [100 ASA] 5248 — so I tend to rate them slightly lower than is recommended. For instance, with the 5279 and [Vision 5289] 800T, I don’t think they’re really 500 or 800 [ASA]. You can shoot them at that rating, but if you do, you’re just going to have to use higher printing print lights. I rate the 5279 at just over 320 [ASA] and the 800T at about 640 [ASA].”

Biddle utilized the 800T stock on exterior establishing shots filmed on a striking location in the oil fields of the former Soviet republic of Azerbaijan on the Caspian Sea. Here, a clandestine smuggling business has been founded by 007’s former enemy, Russian crime boss Valentin Zukovsky, who was first seen in the 1995 Bond film GoldenEye. The decrepit exterior of Zukovsky’s lair, housed in an old refinery, consists of rusted oil derricks surrounded by water. However, Zukovsky has converted the interior of the complex into a caviar factory. “We shot our exteriors on that location at magic hour, using just a few little practical lamps to give the scene some life,” Biddle says. “I used the 800T on all the night exteriors there, which gave me a very particular look. The stock has its own quality as well — it’s slightly browner. I quite liked that.”

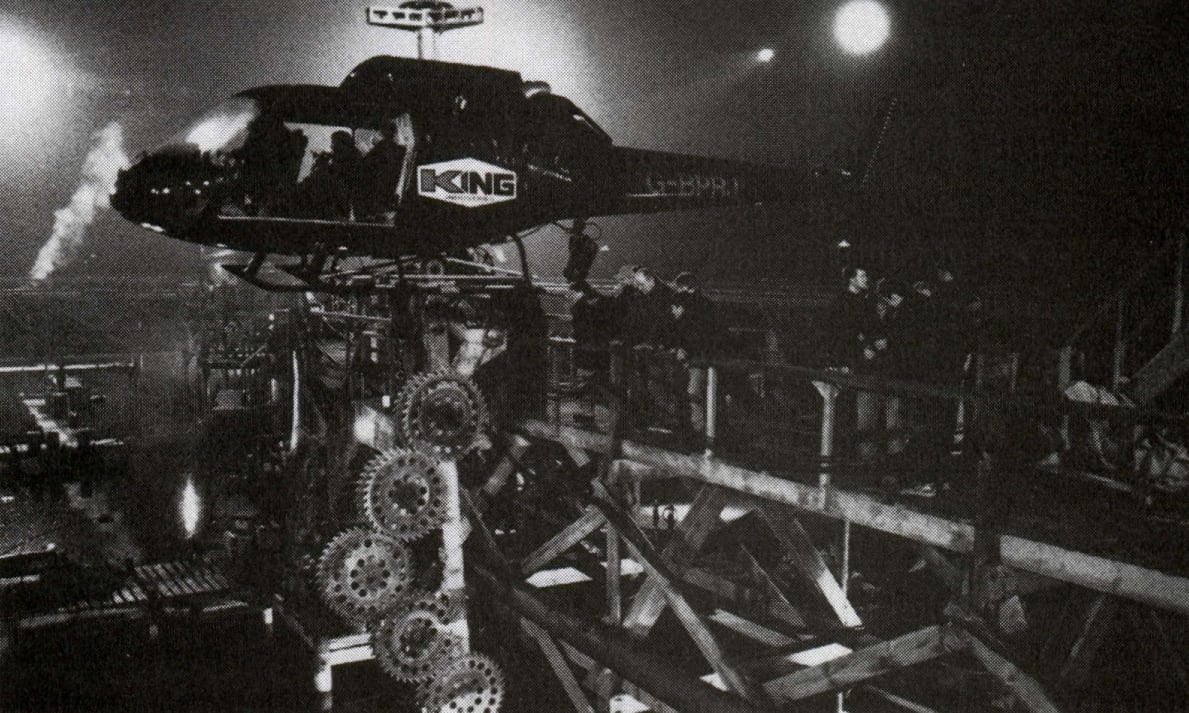

When the production moved back to Pinewood Studios to shoot the caviar-factory interiors (including an action-packed helicopter attack sequence), it was re-created as a massive interior/exterior set on the backlot. To enhance the apparent scale of the structure, production designer Peter Lamont (working on his 15th Bond film) added a huge black backing all the way around the set, which was fitted with forced-perspective catwalks and hundreds of fiber-optic lights representing distant oil fields. Asked if getting all those fiber-optic lights to read against the rest of the on-set lighting was difficult, Biddle insists it was never really an issue: “Funnily enough, it was such a big set that even with all of our lighting, we were only getting a T3 or [2.8/4 split]. We shot the whole scene at about a T4 with the 800T, so the fiber-optics showed up pretty well.”

Biddle lit the inside of the factory primarily with Kino Flos, using them as hanging practicals. “The oil refinery was one of those sets where I walked in and just knew how it was going to look,” Biddle explains. “It had a ‘factory’ look to it, so this was the logical lighting approach.” However, the difficulty in lighting this set was not so much creating enough illumination as it was controlling its tone to support the varied action that was staged within it. This includes a comic scene in which Bond rescues Zukovsky after he falls into a giant vat of caviar, as well as the helicopter attack, which occurs shortly thereafter. Neither Apted nor Biddle wanted audiences to be laughing in the midst of the hard-edged action sequence. “The trick was creating the right balance between being comedic and not getting too much of a laugh, because the scene is supposed to be exciting as well,” Biddle offers. “There’s a line between making it sort of look stupid but not, you know? It’s also an editing issue. Michael and I liked to shoot as much coverage as possible, and then sharpen it all up in the editing.”

The intense beam of a police spotlight raking across the factory windows from outside heralds the start of the helicopter attack sequence, during which the craft uses belly-mounted circular-saw-type blades to slice its way into Zukovsky’s lair — and to bisect Bond’s BMW roadster. To create the illusion that the chopper is flying within the confines of the factory complex on the Pinewood stage, the prop vehicle was suspended from a huge shipyard crane, which was used like an immense Lydecker rig. Able to move in all directions, the helicopter was real in every detail, except that the rotor blades had been removed and would be later replaced with CG versions in post. To add to its menace, Biddle “put these intense spotlights on the helicopter itself. The aircraft moved quite quickly, but not really quickly enough, so I’d move the camera counter to its movement to give it the right speed. Again, that scene will come together in the cutting. The second unit later shot footage of a real helicopter on location.”

However, Biddle didn’t want the only sources in the elaborate sequence to be the glaring police spotlights. His solution was to simulate the fires commonly seen during the oil-refining process, during which excess gas is burned off. This gave the filmmakers the option to utilize a variety of flame sources, and added contrast to the illumination as well, with the harsh spotlights cutting through a flickering orange glow. The fire effects themselves were created digitally, while Biddle created their practical illumination on stage.

The sporadic source lighting emitted by the fireballs erupting from the refinery was generated by 20K running on dimmers. “I think what we had about 20 of them, and we could simulate those explosions quite well by bringing them up,” Biddle says. “I also added a bit of warmth for the fire, depending on how big it was supposed to be.”

The gas-fire source motivation also helped the filmmakers adhere more closely to their script, which “described the rest of the scene as taking place in utter darkness,” Biddle reports, “and then went on with three pages of dialogue. I had to light the scene so you wouldn’t question where the light is coming from. It’s what I call ‘no-lights’ light, and we had to key it with something other than moonlight.”

Cool blue moonlight proved to be an important source elsewhere in the film, though, and Biddle generally creates his version of this lighting effect through some basic timing work. He details, “I don’t particularly like the blue color of HMIs, so instead of using one of those, I’ll use a tungsten source for the moonlight, and then warm up my interior lights with some sort of CTO for [temperature] contrast. I then have the lab to print the scene for normal skin tones, which makes my tungsten moonlight key go slightly cold.”

Due to the epic scale of The World is Not Enough, the caviar factory proved to be one of Apted and Biddle’s rare opportunities to shoot an action scene in its entirety. The other action sequences were generally handled by up to three additional camera units, supervised by veteran stuntman and second-unit director Vic Armstrong, who handled similar duties on the preceding Bond film, Tomorrow Never Dies, and began his long association with 007 by playing one of the Japanese assassins in 1967’s You Only Live Twice.

Despite the huge amount of work involved, Biddle regrets not being able to shoot every scene in the picture, as he had on such action and effects-heavy projects as Event Horizon and The Mummy. “I would have loved to have shot some of the second-unit stuff, but our units shot [concurrently] for six months, so we couldn’t have done it any other way. We’d still be shooting now!”

Apted, Biddle and Armstrong initially split the work up between the first and second units based on storyboards of each sequence. “We found that the storyboards didn’t last very long, though,” Apted says with a smile. “Each sequence was a slightly different animal, a different challenge. Vic would do the scenes that were very stunt-driven, and then I would take in the first unit and do the extra bits and pieces we needed. Conversely, I’d take the action scenes that were more actor-driven, and then Vic would finish them up.

“There was so much to do that the division of scenes was really determined by whether or not the audience would be able to tell if it was the actual actor in the shot,” Biddle adds. “There was no artistic thinking in that decision. It was more like, ‘If you can’t see it’s Pierce Brosnan, it’s second unit.’ We generally started shooting on any given set first, even if it was for just a couple of days. That way, my gaffers could pre-rig the set, so the look and the lighting style was determined before the second unit went in; they could then go from there. I think that’s really the key to getting good second-unit stuff.”

However, there were a couple of sequences that were shot by Armstrong and second-unit cinematographer Jonathan Taylor ahead of the first unit, including a stunning boat chase on the Thames River. In those instances, communication was vital to maintaining a consistent look.“I just made sure that I talked to Jonathan,” Biddle says. “That sequence is a good example of why, when you go on a location scout, you’ve got to do it well. You have to determine, especially with the assistant director and the director, that you’re going to shoot in one direction all morning, even if that means cutting up the scene and then doing the reverses in the afternoon.

“They had a tricky task while shooing the boat chase, because the weather changed so many times — it was either raining or the sun was out. But my rule on exterior shooting is to always try to shoot things backlit, because then it’s easier to match. If it gets overcast, they could move on to some sort of weather coverage stuff, but in the end, they’d have to keep shooting. When you see this scene, there will be shots where the sun goes in and out, but hopefully, the action and how Vic positioned things will help us get away with it. The boat sequence was difficult, but I think it turned out well.”

In some ways, Apted and Biddle had an easier time of it when they came in after the second unit had shot the stunts. “By the time we got to shooting those scenes, they had usually been cut together, so we knew exactly what shots we had to do, which made things easier,” Biddle remembers. “In general, the shots that they left over for us to do were all of the ones featuring Pierce, so it was an absolutely precise job.”

Of course, shooting what amounts to a series of actors’ inserts creates its own difficulties, particularly in terms of making those closeups feel integrated into the overall action. For Biddle, the key to these dilemmas is movement. “You have to repeat what the second unit has done,” Biddle explains. “That is, you design each of your shots so the editor can use them instead of what second unit photographed, although you then wouldn’t have the big stunts. I think the best way to approach these inserts is to do them exactly the same way as you would do a standard wide shot. That way, the camera moves become more exciting, so when you cut to the insert shot, it just looks as if it’s part of the sequence, and you might find that you can use a bit more of it in the scene.”

Despite the epic scale of The World is Not Enough, certain sequences are quite intimate, and required Biddle to rely on finesse rather than broad strokes. In one such sequence, Bond and Dr. Christmas Jones make an escape inside 007’s inflatable coat. Supplied by Q, this gadget becomes a protective bubble, the interior of which resembles the inside portion of a giant balloon. Biddle shot the low-key scene with 5279 and employed a favorite gadget of his own, a miniature Dedo light. Using Bond’s illuminated watch as his ostensible source, Biddle served as a lamp operator and mimicked actor Pierce Brosnan’s arm movements to keep the glowing watch face consistent with the Dedo’s beam on the two actors. “I use Dedos quite a lot for eyelights and things like that,” Biddle reveals. “The company’s got all these different versions of them, and you can flag things up just with the barn doors on them. You can also hold a Dedo right in your hand, which is what I did for this scene. I just floated it around, bouncing the light off the inner surface of the ball. It was really easy.”

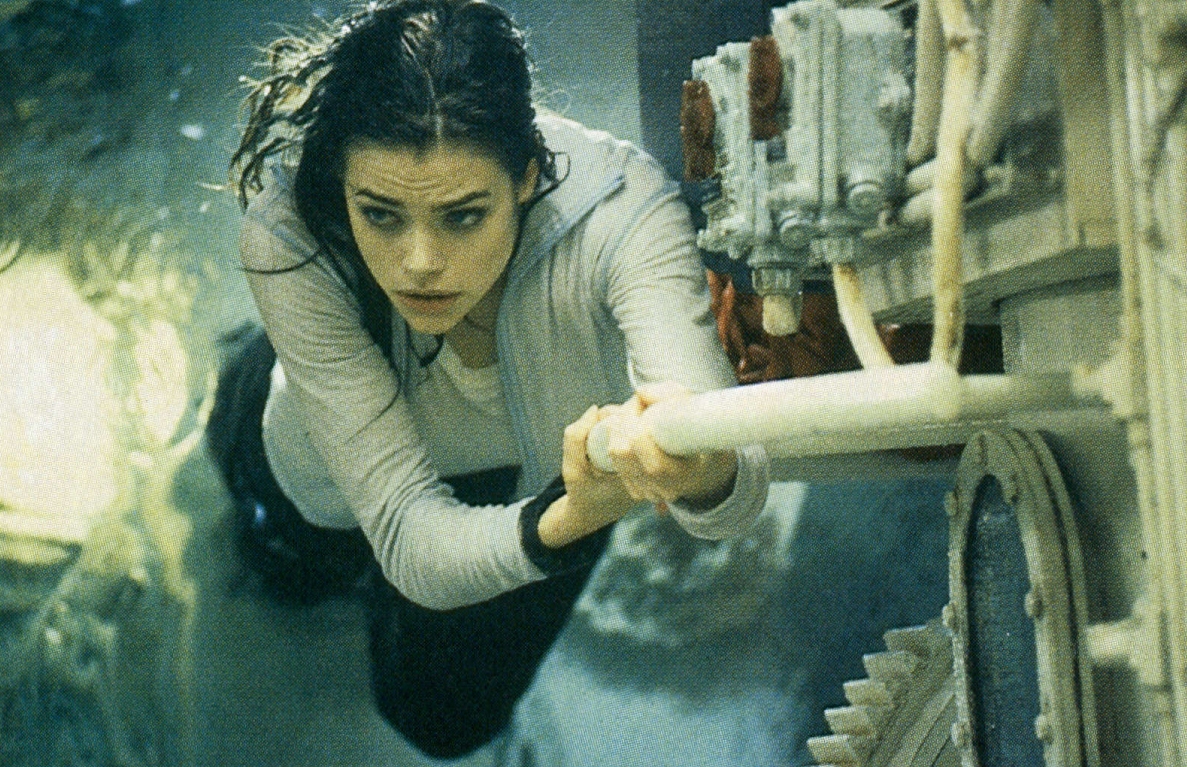

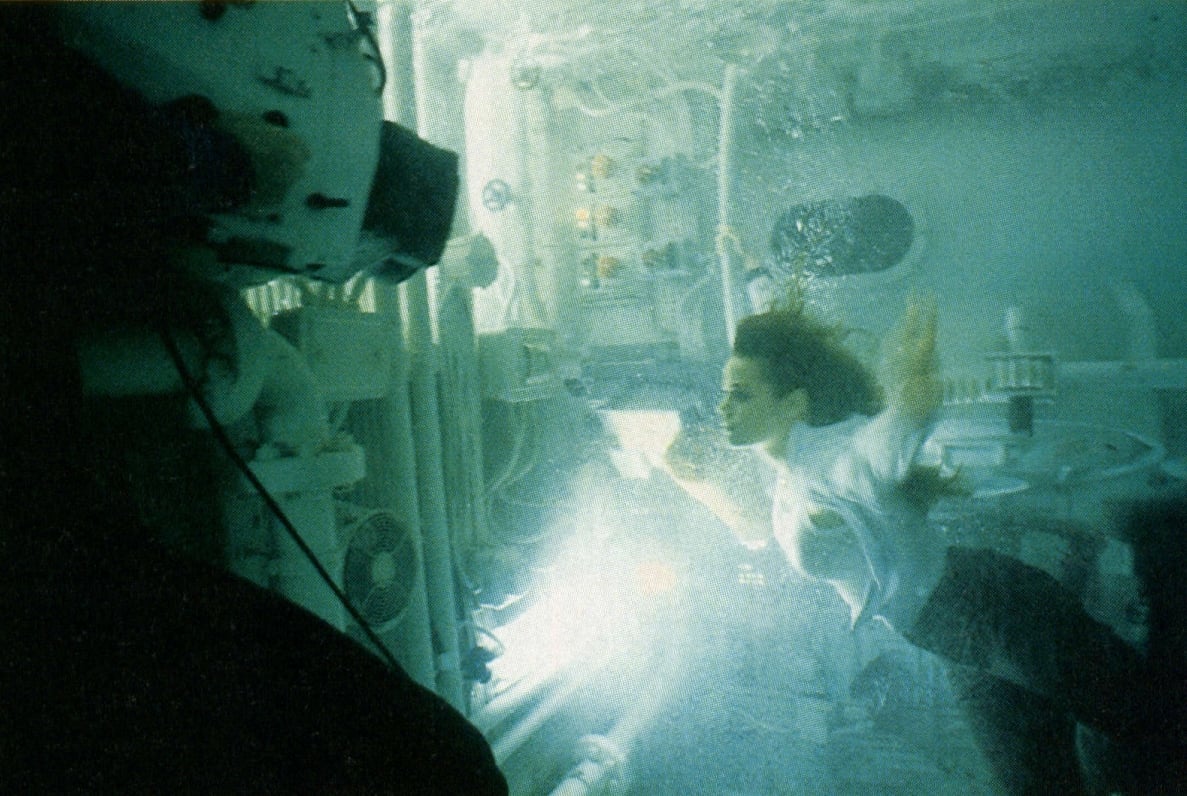

An even more confined space was reserved for the film’s climax, which takes place almost entirely in and around a sinking nuclear submarine. The vessel’s main control room set was built on a gimbal so the interior could rise in the air and tip over 90 degrees. For his lighting, Biddle relied on production designer Peter Lamont — his old colleague from Aliens — to insure that the proceedings could be illuminated almost exclusively with practical. “Peter’s done a lot of that stuff and knows what practicals to use,” Biddle says. “I enhanced those a bit with my lamps, but I basically used the practicals. All of the Kino Flos, little bulbs and flashing lights in the sub had to be waterproofed, though, because the set literally went underwater.”

While Biddle generally found that he was rarely short of the time or money he needed to practice his craft on The World is Not Enough, he and Michael Apted were being pressured to complete the picture by the time they began shooting the submarine climax. “It was near the end of our schedule, and they wanted to get on with the cutting,” Biddle says. “That set wasn’t a very enjoyable place to be; it was very tight, and for certain scenes, everything had to be bolted down because when it went over and then down, everyone was working upside-down. The problem was how much time it took to do it, really, and it seemingly took forever. The way I look at things, if you’ve got the time, you can do anything.”

Biddle left the shooting of the exterior underwater sequences, wherein Bond swims out of the submarine and comes back in on the deck, to Armstrong and Taylor. The trick there was matching the tank work done with Pierce Brosnan at Pinewood Studios with miniature photography shot in the Bahamas. The look of the clear tropical waters was difficult to re-create in the studio, so Biddle and Taylor did it largely through the lab rather than onstage. “We were going for this blue-green look because that’s what they had in the Bahamas,” Biddle explains, noting that water filters out various portions of the color spectrum at deeper and deeper points. “Blue is the next-to-last color to go, and all of the red is gone by that point. Because we were working at the blue point in the spectrum, the scene wasn’t easy, but it was relatively straightforward to grade by taking out all the red.”

Despite the hard work and lengthy shoot — the film’s first and second units both shot for well over 100 days — both Apted and Biddle are pleased with the result of their labors. “Although it was a fantastically long shoot by my standards, you couldn’t want to work with better people than Adrian and Vic,” Apted concludes. “I hope it’s what people want and maybe a tiny bit more, you know? It’s been terrific fun.”

Vic Armstrong: Thrill-Seeker

The James Bond franchise may be the final holdout from the world of digital technology. During the course of 19 films, the creators of the series have prided themselves on the fact that the most spectacular images are created almost entirely in-camera. “The thing about Bond films is that the spectacular footage is all real stuff,” states director Michael Apted. “On The World Is Not Enough, we used digital effects very sparingly. I think that’s the hallmark of the franchise: it is dangerous and people do the stunts. It is truly man against man, or man against nature, and I think it shows. It takes a hell of a long time to shoot those kinds of scenes, which is why I had a second unit that was running the whole time I was.”

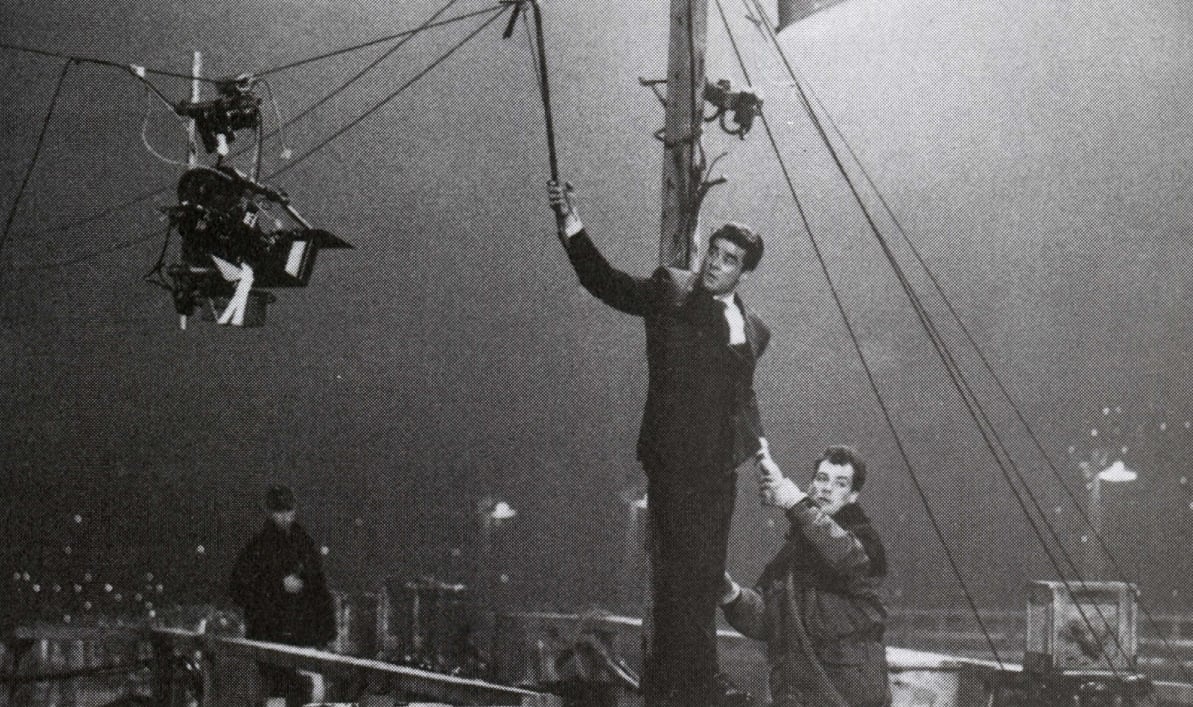

Indeed, the emphasis on real action put a special burden and emphasis on the film’s second unit, which was helmed by veteran stuntman Vic Armstrong, who had handled the same assignment on the previous Bond film, Tomorrow Never Dies. Armstrong began his lengthy association with the secret agent in the glory days of the late ’60s, playing a Chinese assassin sliding down a rope in You Only Live Twice, and then stunt-doubling George Lazenby in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and Roger Moore in Live and Let Die. He was both the stunt coordinator and a stuntman on Never Say Never Again, and shot tests on Timothy Dalton’s first Bond, License to Kill. Armstrong remarks, “Second units are really tough, because you have to try to match somebody else’s style, and do what they want. You’re part of a team, but that’s what the game is all about.”

Generally, Armstrong’s second unit would come in after Apted’s first unit had finished shooting with the principal actors. “We did the major sequences that way — including the boat, ski and helicopter sequences. It’s by far the most economical way of doing it, otherwise there’s so much time wasted and energy wasted — especially if you’ve got the actors there for a limited time. But there were times when we would go off and shoot whole sequences and then put the actors into them. In those situations, Michael’s first unit became the good old insert unit!”

Perhaps the hardest part of doing good second-unit work is slavishly following the dictates of the first unit. “Sometimes you just have to subjugate your own instincts to make it cut with what’s already there,” Armstrong admits. “When you go into second-unit work, you have to understand that your objective is to match the other parts of the movie, which can be pretty tricky. You need to have a good crew with you. You have to get a good A.D. like Terry Madden, and a grip like Kenny Appethal, whom I think is the best in the world. Kenny puts a camera wherever I want it: on the river, on skis, underwater. I’ve also got a great cinematographer in Jonathan Taylor, who’s a super technician and a very talented lad. On every shot we did, we tried to make beautiful action sequences. The night sequence with the helicopters attacking the factory was all backlit with fire and steam, and it’s a very visual sequence. Even the skiing sequences were all backlit.”

Armstrong sometimes had to place movie stars — as opposed to trained stuntmen — in the line of fire. For one sequence, the first unit had shot Bond making his escape from an exploding nuclear facility using a stunt double, but Armstrong was asked to pick up some close-ups of Pierce Brosnan. He quickly realized that he could stage the entire gag with the star in a single shot. Armstrong’s goal was to have Brosnan swinging on a chain just inches ahead of an enormous fireball, which called for tremendous caution on all sides. “If you’re going to do it completely safely, you do it with doubles,” Armstrong says. “This is a classic case of putting an actor in the same position I’ve been in before myself, so I imagined that if I was hanging there on that chain. I wasn’t thinking like I was somebody who selfishly wants a spectacular shot.”

Armstrong and his crew set up the shot on the famed Bond stage at Pinewood Studios. As Brosnan swung on the chain, a series of pyro effects were triggered just seconds after the actor passed each of the charges. “You can see the fireball chasing Pierce, right on his ass,” Armstrong says gleefully. “Because of the long lens on the shot, the explosions were going off 10 to 15 feet behind him, which was hell for the focus pullers because I only wanted to do the stunt once.

“There was a lot of pressure on everybody to get the shot. The special effects crew were cracking themselves because they had to fire the ‘bangs’ at certain lengths. If one of those things had been wired up wrong, which I’ve seen in the past, and one went off prematurely or out of sequence — i.e., in front of Pierce — he’d have gone right through the fire, you know? Although we dressed him up in a fire-retardant suit and other protective gear, the element of danger was still there. It was a money shot, and it worked — Pierce is as safe as pie and the scene looks great.”

Still, Armstrong insists that no challenge was too great in terms of delivering the level of excitement that Bond fans crave. “This show was pretty tough, but I had great backing from the production, which gave me whatever I wanted,” he enthuses. “I spent the budget of a medium-size film just on the second unit, but we delivered the goods!”