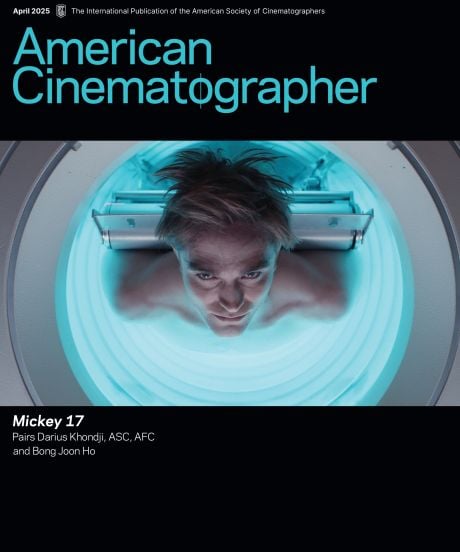

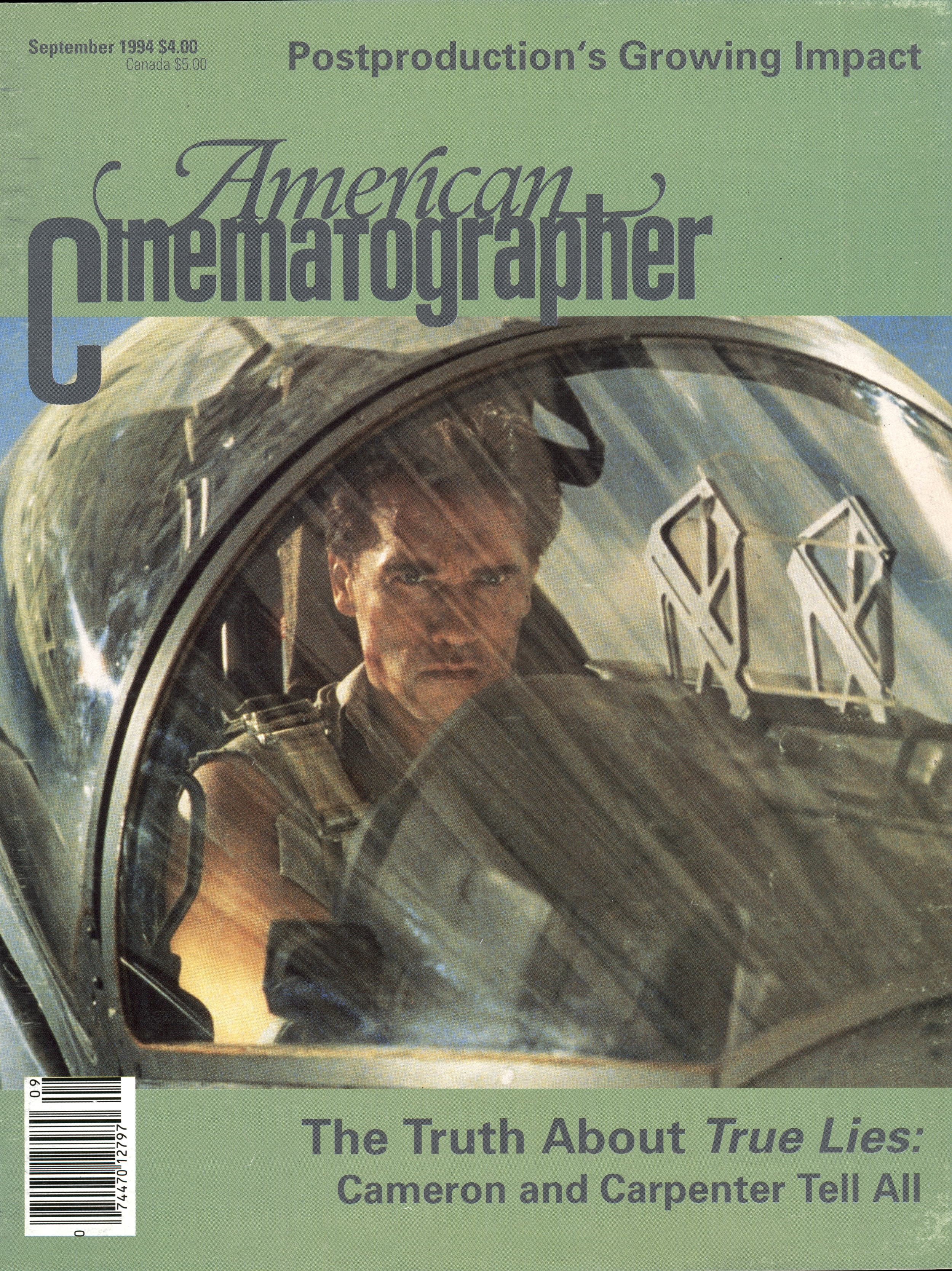

True Lies Tests Cinema’s Limits

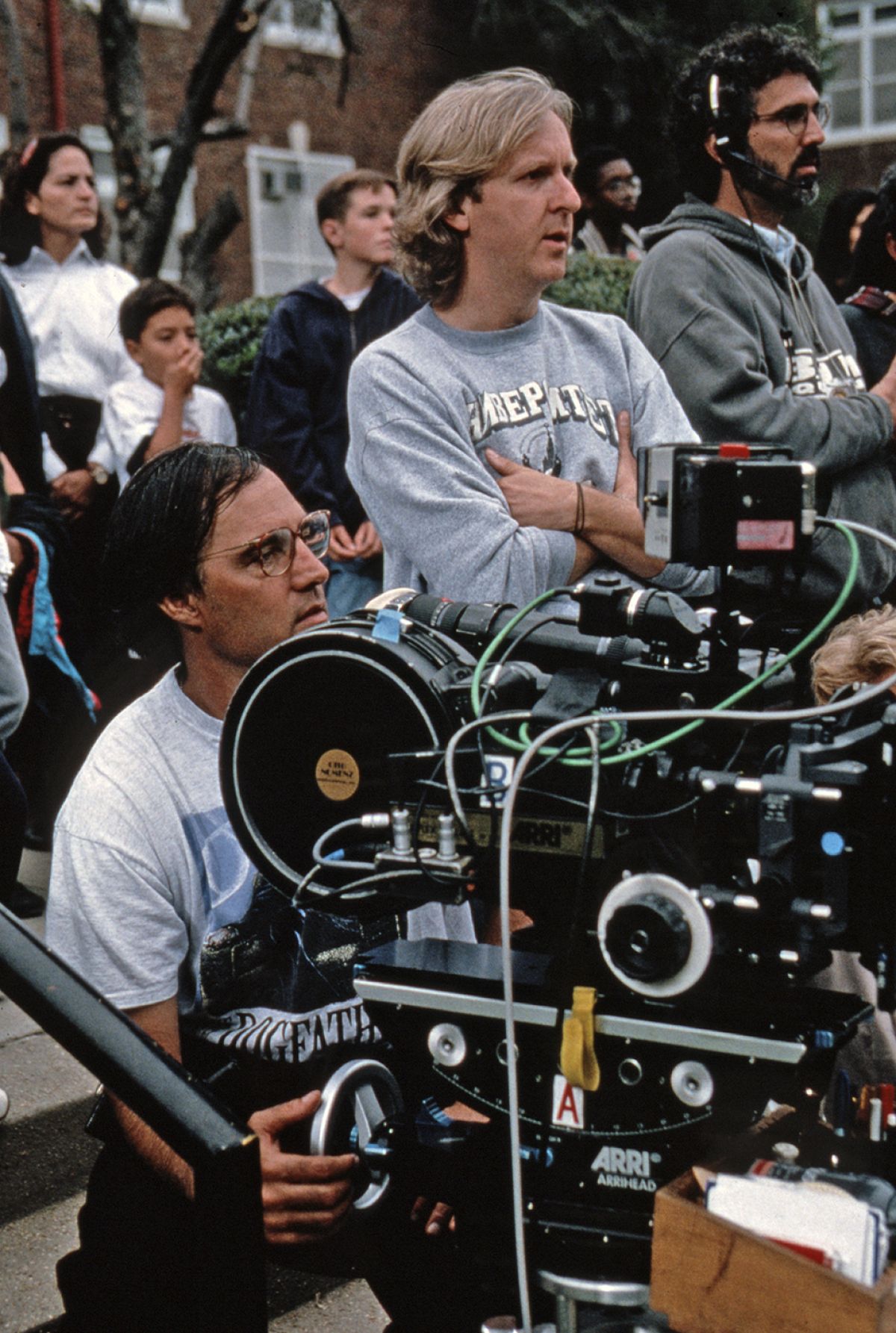

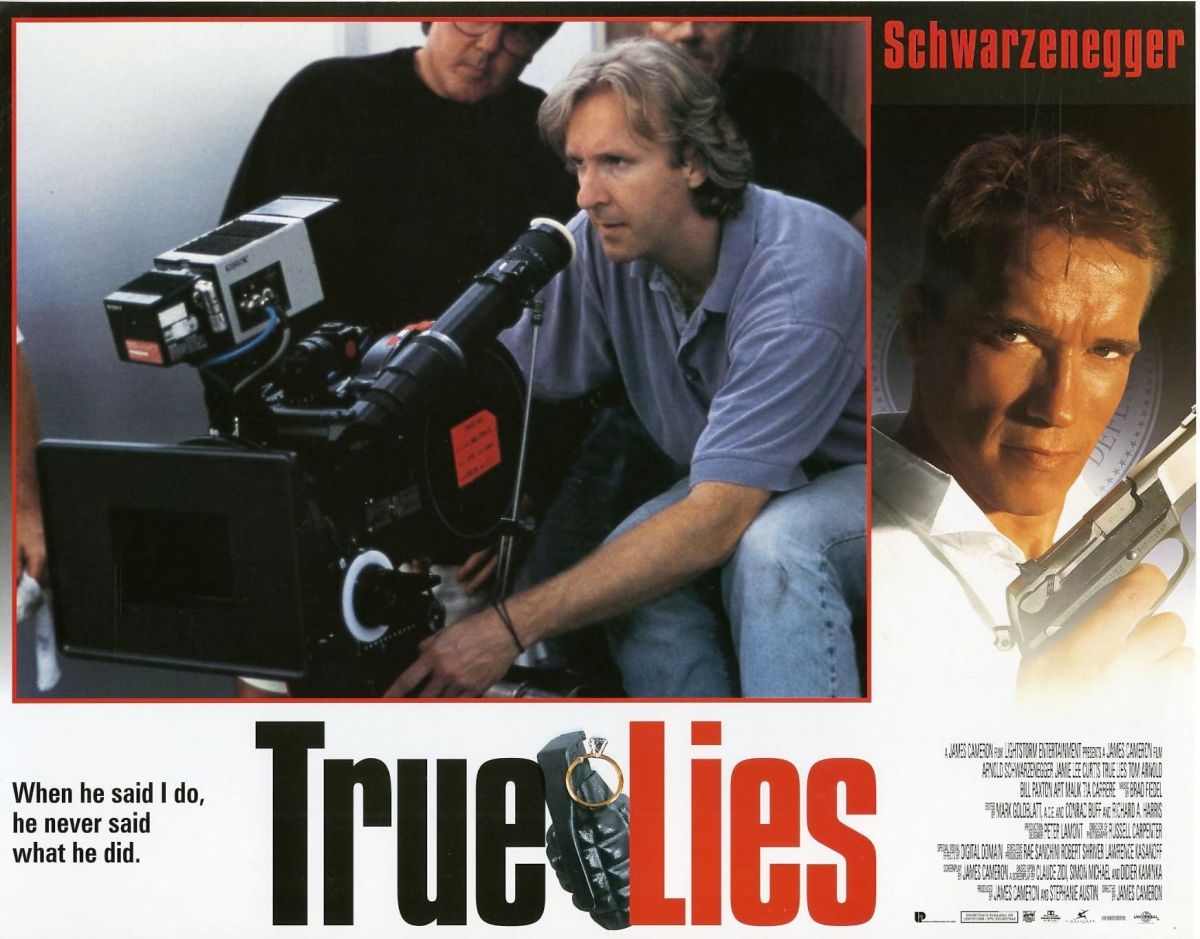

Director James Cameron and cinematographer Russell Carpenter marry domestic farce and dynamite action footage.

Unit photography by Zade Rosenthal

“In sickness and in health,” “through good times and bad” and “‘til death do us part” are incantations familiar to wedded partners the world over. These solemn vows may also sound familiar to crew members who have worked under the rigorous whip hand of director James Cameron, a modern master of the action-adventure genre.

"Working for Jim is like playing the toughest room in Vegas. Because he's such a perfectionist, and because of the massive scale of his pictures, you know that some days are going to be agony," admits director of photography Russell Carpenter, who was collaborating with Cameron for the first time on True Lies. "But when I watched the finished film, all I could think was, ‘My God, it was all worth it.’ It’s not often that you get the chance to create images that no one has ever seen before.”

“When you see Harrier jets and helicopters listed under ‘equipment,’ you know it’s going to be a tough day.”

— Russell Carpenter

Described by Cameron as “a metaphor about modern marriage,” True Lies does indeed deliver the goods, pushing cinema's limits in spectacular fashion. Rumored to have a budget in excess of $100 million, production consumed seven months (from August 1993 to March ’94), during which time cast and crew often found themselves toiling through highly stressful, seemingly endless workdays. The shoot's logistical demands would have tested Patton himself, and call sheets often resembled inventories for a second invasion of Normandy.

“When you see Harrier jets and helicopters listed under ‘equipment,’ you know it's going to be a tough day,” Carpenter chuckles.

During one legendary stretch while shooting in the Florida Keys, the crew worked for 12 days in a row — the last four without stopping for lunch. Even the general himself concedes that the campaign exacted a heavy toll on the troops. "We all got a little burnt," Cameron says. "The Florida shoot was probably our low point, because it was right before Christmas and everybody wanted to go home for the holiday. It was absolute, flat-out, turbocharged filmmaking. We all flew back together, and it was like coming back from a war. But in January, everybody came back to work with this weird feeling of being the platoon that had been through hell and survived. There was a sense of bonding, and the shoot was cake from that point on."

Aware of his well-documented reputation as a taskmaster, Cameron defends his means with two important ends: the big screen and the box office. "There were no easy shots on this movie, and if they were easy I found a way to make them hard; I'm sure anyone on the crew can attest to that," he says. "But to me, that's what filmmaking's all about. You just push the envelope every day. Some people respond to that, and those are the people I work best with. Russ got into it, [B-camera and Steadicam operator] Jimmy Muro got into it, and so did lots of others. People who are real filmmakers in their heart and soul get into it. I don't get along too well with people who are just punching the clock or trying to slide through it; they can go shoot a sitcom or something.

“But you know what that translates into? A lot of good value for a $7.50 ticket. The money is up there on the screen, because that’s the kind of movie I make.”

— James Cameron

"Yes, the budget was big," he adds. "But you know what that translates into? A lot of good value for a $7.50 ticket. The money is up there on the screen, because that's the kind of movie I make. At a time when people are being conditioned to expect less and less from a movie — because budgets are getting so high, and it's getting more difficult to do really mind-blowing stuff — we just do it anyway. People should feel good about that, and judging by the returns on most of my pictures, they usually do."

With True Lies, however, Cameron is gambling that his hardcore audience — as well as the general viewing public — will follow him into previously uncharted comedic terrain. Unlike the director's prior pictures, which offer a selective number of gags to leaven the mayhem, True Lies is, at its core, a domestic farce taken to fantastic heights. The film's plot crosses Boris and Natasha with Dagwood and Blondie: Harry Tasker (Arnold Schwarzenegger) is a crackerjack spy whose assignments from the top-secret Omega Sector take him on wild, Bondian adventures all over the globe. But to his demure wife, Helen (Jamie Lee Curtis), and rebellious daughter, Dana (Eliza Dushku), Harry is simply the Good Provider and the Boring Dad, a computer salesman whose idea of excitement is hawking the latest software products. The Tasker women are also unaware that Harry's jocular buddy Gib (Tom Arnold) is actually a fellow agent who faithfully accompanies his friend on his clandestine exploits.

The Taskers' daily routine changes dramatically, though, when Harry is assigned to track down the Crimson Jihad, an Arab terrorist faction that has somehow gotten its hands on four thermonuclear warheads. Led by the hubristic Aziz (Art Malik), the group intends to destroy four different American cities unless its fanatical demands are met. It's up to Harry to save the day, but the superspy's concentration is short-circuited when he accidentally discovers that his beloved Helen may be having an affair with a suave mystery man (Bill Paxton). Harry marshals all of his snooping skills to find out if Helen has been unfaithful, and in the process manages to drag his family into the midst of a national nuclear crisis.

Translating this outlandish tale to the screen was a Herculean task, but Carpenter was up to the challenge. Previously known for his eye-catching work on relatively minor films (Lady in White, Solar Crisis, The Lawnmower Man, Hard Target), the director of photography suddenly found himself facing some of the most complex setups in movie history. When asked why he chose Carpenter over more well-known cinematographers, Cameron replies simply, "Dialogue. I've got to work with a director of photography I can talk to, and whom I feel has something on the ball creatively. My reason for going with Russ wasn't so much his past work — though that was sound — but his enthusiasm and willingness to try new things. I had actually interviewed Russ for another film, The Crowded Room. He came back to me with a booklet of photos that he'd cut out of magazines, saying, 'This is the look I think we should use for this, or that.' Even though I didn't necessarily agree with him on all those things, I saw that he at least had an opinion and a vision. He brought something to the table, and I respected that."

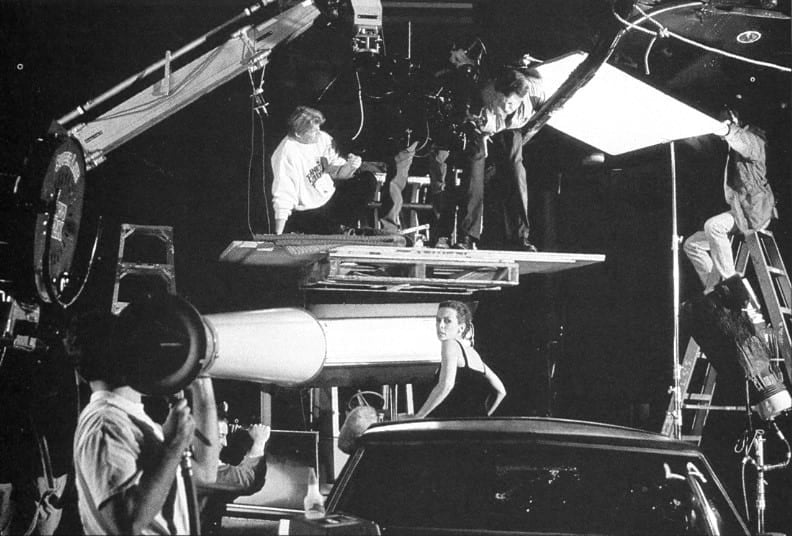

The "table" in question, of course, was laid out for the cinematic equivalent of a four-star Thanksgiving Day feast. In preparing the meal, Carpenter had the advantage of the finest cookware money could buy. The production's camera truck carried close to a dozen cameras at all times, including two Arri 4 BLs, two Arri 3's, three Eyemos, a Moviecam for Steadicam work, Cameron's own Arri 2C, and a modified Arri dubbed the Fastcam ("The Fastcam was basically a glorified Pogocam," Carpenter explains. "The image from the Fastcam went through a head-mounted video system so we could see what the camera was seeing.”) His basic lenses were Zeiss primes and Cooke zooms.

Carpenter also enjoyed the kind of logistical perks that only a blockbuster budget can support. In order to achieve a consistent look for his night exteriors, which featured the cool blue tint that has become a Cameron trademark, the cinematographer used all of the manpower at his disposal. "Jim believes in a luminous moonlight look, which he calls 'lucid night,"' says Carpenter. "We didn't use any filters to achieve it. We exposed the key side of our night exteriors almost up to key, using uncorrected HMIs. The blue look was later enhanced in the timing. For the night street work in Washington D.C. and Los Angeles, location scouts gridded the cities and found all of the streets that are currently lit with mercury vapor lamps, which tie in extremely well with HMIs. What you'll notice in 90% of the shots is that all of the street lighting is the same color as the HMIs. The scouts would come to us with maps and then we'd go out and spend the night driving to all of the places that had mercury vapor. If we loved a location but it had sodium vapor instead of mercury, we'd have the city go in and replace those lamps for us. We wanted the environmental lighting to support our own lighting, which included Condors, Muscos and Night Suns.

"We used combinations of units because we wanted the night shots to have details and depth," he continues. "Jim loves to see into the distance, and that often means lighting into the very deep background. We usually combined our Muscos and the Night Sun. The major Muscos are excellent for lighting huge areas, but you can't flag them, so we'd usually bring our Night Sun into the foreground area, backlighting or lighting three-quarter-back. We had a lot of control over that light in terms of what we could flag and shade. We also used the mini Musco, which allowed us the luxury of shooting at different speeds."

Elaborating upon the concept of "lucid" night photography, Cameron explains, "There are a lot of cues that tell the viewer it's night, but you can see everything. You get that look by a combination of lighting and exposure: a lot of rim lighting for separation; a lot of fill light, especially protecting the actors' eyes; and a lot of mixed light in terms of color — full-blue HMI with white. We used a lot of white light to accent. I'd never done that on this scale before, and neither had Russ, but the approach was based on a couple of shots in The Abyss that I really liked, especially one scene that takes place in a control room. The scene is mostly blue, but there's a white light on, and that white accent sort of reminds you that you're looking at a blue image. A lot of people just go monochromatically blue; the eye adjusts to the blue, and after awhile it becomes sort of a black & white image with a blue filter over it, and it's not as interesting. On True Lies, I said to Russ, 'Let's take that idea [from The Abyss] and expand upon it.' We'd either fill with white in a night scene, or we'd rim with white and fill with blue."

The overall look of the film, Cameron says, is more traditional than the visual schemes of his previous efforts. The director sought to infuse True Lies wth the spirit of the James Bond films and television shows like The Man from U.N.C.L.E., but shied away from outright visual homages. "I don't believe in copying the look of other films," he maintains. "Sometimes I'll sit and drink tequila and watch MTV with the sound turned down to get new ideas for shots, but looking at other movies for inspiration is just not valid for me.

"True Lies is slightly stylized, slightly unreal, but not so much in the cinematography," he adds. "We didn't try for the vampy, unreal look of a film such as Dick Tracy, and there's really nothing in this movie like the T1000 stuff from T2. It's not a science-fiction film, so you're not going to see imagery that has that degree of surreal impossibility. The outrageousness of the film comes from the situations, which are pretty wild. With the look, we're trying to say, 'You're not supposed to take this seriously; it's a romp.' This film is more stylized than my others in the sense that you're meant to be a bit outside the movie, having fun with it. It's really a story about a marriage, and everything else is window-dressing.

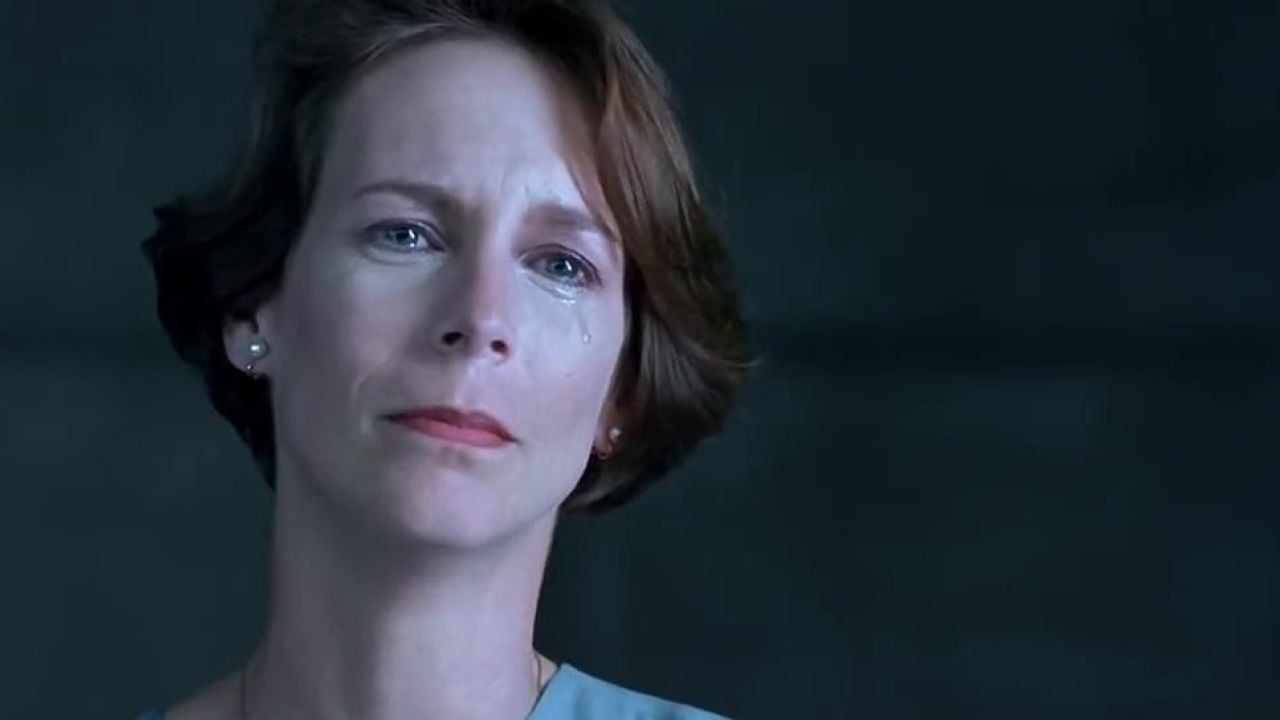

"We tried to give the domestic scenes a warmth and lightness, and then later we tried to lend them an almost black comedy feel, colder and a little more expressionistic — nothing radical, but just enough so you can feel a shift in tone. Later, in the action stuff, we went for lucidity and clearness, an almost hyper-real look that allows you to see everything without it feeling blown-out. I spent a lot of time with the printing and color timing, and it definitely came through in the release prints."

Both Cameron and Carpenter maintain that those prints — struck in both 35mm and 70mm — are among the finest they have ever produced (release prints were handled by Deluxe, while CFI provided interpositives and dailies). The filmmakers reserved special praise for the quality of the 70mm prints, which were blown up from the 35mm negative. Cameron reports that his past attempts to strike 70mm prints from 35mm negative have been satisfactory but hardly spectacular. "The 70mm prints of this film are shockingly great in terms of image quality," he states. "This is the fourth time I've printed in 70, and it's the first time that the 70 prints have looked substantially better than the 35s. The 35mm prints of True Lies are very good, but the 70s look like IMAX by comparison. We ran tests side by side, and it was no contest."

Cameron attributes the startling improvement to Kodak's new 5244 EXR color intermediate stock. 5244 employs ultra-fine silver halide crystals and a new generation of advanced color couplers (chemicals which form dyes in the red, blue and green sensitive layers of color negative film in proportion to colors in the scene) to produce cleaner, sharper images with considerably reduced granularity. This clarity shows up most dramatically in the film's blacks, which Cameron describes as "bulletproof."

To best exploit the film's array of eye-popping scenarios — and to give themselves some vertical headroom to adjust tricky images ("Harrier jets don't always line up the way you want them to," Carpenter laughs) — the filmmakers opted to shoot in the Super 35 format, which was also used for Terminator 2. In order to ensure the best possible grain structure, Carpenter exposed the film's stocks (mainly Kodak's 5296 and 5245, but also some 5293) fairly conservatively.

The duo's daily working method was influenced by Cameron's use of a device called the Vid Stick, a handheld video viewfinder he designed with the help of his brother Mike. "Russ and I fell into a groove which went something like this: we'd come onto the set, talk about the upcoming scene a bit, and then I'd start setting up with the actors and block the shot with the Vid Stick. Let's say I wanted to work on a 35mm lens: I'd ask for a 35 from the primes box, stick it on the video viewfinder and switch on the transmitter; the image would go simultaneously to a deck in my hand and back to a separate video station. After turning on some lights just to rough things in, Russ would watch at the video station, or walk with me as we moved through the shot, which would usually be a tracking master, a Steadicam master, or possibly a crane shot — although I could only approximate what a crane shot would look like, because I couldn't hold the Vid Stick any higher up than about eight feet, the height of my reach. Usually I'd try to block the master, lay it down on tape, and then pick off some of the coverage at the same time. That process would give me a rough tape of what we were going to shoot for the next couple of hours, with the actors and the dialogue. If there were any questions about framing, or how the camera was going to move, we'd have it all on tape. Russ could go off to work on the lighting, using the tape for reference, while I went off to consult with the actors on their performances.

"Eventually, we'd get back together at the monitor, and he'd say something like, 'You did this twice, and the second time you popped over a little bit to the left, but I could really use the space by that palm tree.' At that point there would be a negotiating phase, during which we'd negotiate the frame line based on the video. Then we'd start shooting. This method didn't necessarily speed up the process, but it made it a hell of a lot more precise."

Understanding that most viewers will enter the theater with a "Go ahead — impress me" attitude, the production team went for broke while shooting the opening sequence of True Lies. Demonstrating espionage expertise and je ne sais quoi in equal proportions, Harry scuba-dives under a frozen lake and past an elaborate outdoor security detail at a Swiss chateau; peels off his wetsuit to reveal the tuxedo beneath; infiltrates a swanky cocktail reception; accesses a private computer in an upstairs study; and eludes capture by dancing a red-hot tango with beautiful art dealer Juno Skinner (Tia Carrere). Eventually, Harry's nonchalance backfires when he attempts to exit the premises by simply walking out the front door. When a guard asks to see his invitation, Harry must resort to Plan B; distracting the guards by detonating an explosive charge via remote-control, he races through the chateau's snowy, tree-lined grounds as Doberman pinschers and assassins on snowmobiles give chase. As Harry wends his way through the woods, guns blazing, his Omega Sector cohorts, who have monitored his every move from a nondescript van, skid along icy roads toward a rendezvous point.

This sequence alone required an impressive array of photographic tricks and special effects. The establishing shot of the Swiss chateau involved a blend of several elements: a mansion in Newport, Rhode Island served as the "chateau"; the water was photographed near Lake Tahoe; the background Alps were provided by matte artists; and the foreground pier, shot during principal photography, was enhanced by John Bruno and his corps of technical wizards at Digital Domain, Cameron's new effects company. The elements were then composited seamlessly in digital post. [Ed. Note: in-depth coverage of the film's effects appear in AC Dec.'94]

The various effects elements, recorded with VistaVision cameras, were shot at the same time as the first-unit photography. "Jim didn't want to limit the [effects] shots at all in terms of movement," Carpenter notes. "He would have the VistaVision cameras do whatever a normal production camera would do, and then the burden would be on the people at Digital Domain to make the background mattes work for the movement."

Carpenter's own burden on the sequence involved several stages. The underwater footage was shot in a wave research tank at a facility in Escondido, California and lit with sea pars below the water and 12Ks from above (the facility's ceiling was also blacked in to keep skylight out). The interior scenes at the mansion were complicated a bit because the crew was prohibited from hanging fixtures. Carpenter solved this problem by bouncing 7K Xenons off floating silver balloons suspended from thin filament wires. Further supplemental lighting (2Ks and IKs) were hung from an aluminum grid system that was painted the same color as the walls for camouflage.

The exterior chase scene, meanwhile, combined logistical planning and some old-fashioned, on-the-spot ingenuity. "The problem with lighting for action sequences on the snow and at night is dealing with extreme contrast on the slopes — trees that would block things out, and snow that would go too hot," Carpenter says. "We shot a lot of the sequence at Boreal, a ski resort near Lake Tahoe, and the rest at Donner Pass, in California. Getting the lights to the top of the resort was very difficult. We decided to light four basic quadrants, so we had four huge, 30- foot towers assembled in the different areas, and then placed 12Ks and Xenons on top. The lights and everything else were helicoptered in. Working in the snow is like working underwater; you're up there on the side of this mountain, and you're thinking, 'I just don't want to fall and slide 400 feet on my backside.' You know that when you ask to lay a dolly track, or move a light, it will take three or four times as long as it would in the studio. This sequence was also tough on the electrical crew.

"The first unit spent three or four days there, and the second unit, led by director E.J. Foerster and cinematographer Shelly Johnson, spent about five more days. While the first unit was off shooting other scenes, the second unit blocked in the lighting for all four quadrants. Fill light was usually just bounced off the snow. Our thinking was, 'We've got the world's biggest bounce cards right here/ so we would fill by bouncing a conventional HMI into the snow. If the shot was moving, we might track the action with a Xenon light. A lot of this show was done with rear-screen projection, and some of our biggest lighting challenges involved lighting mountain roads for the rear-screen shots. We found a nice winding road up in Donner Pass, and we put our Night Suns and Muscos up along this sides. Because of the reflectivity of the snow, we were able to light huge areas for both regular production photography and rear-screen plates.

"One major difficulty in shooting snow is that if you're back-lighting snow, it will sometimes go much too bright," he adds. "That sometimes works to your advantage by giving you dramatic contrast, but it can also just blow out the scene. Jim came up with a solution that was pretty simple and brilliant at the same time: we just raked the snow at a 90-degree angle from the light, and it completely broke it up and knocked two stops off the snow. I thought that was really clever."

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of True Lies is the film's ability to top itself repeatedly as it builds toward its high-octane finale. As exciting as it is, the snow chase is just an hors d'oeuvre for the next major sequence, a truly epic crescendo of action that begins in the streets of Washington, D.C., when Harry and Gib notice that their truck is being followed by a carload of gun-toting terrorists. In an attempt to lure the bad guys off the street and into a showdown, Harry strides into a posh hotel, tracking his pursuers' movements with the help of a microscopic video camera hidden in a pack of cigarettes (the camera transmits a picture to a sophisticated pair of sunglasses, giving Harry electronic "eyes in the back of his head"). The terrorists eventually follow Harry into a hotel bathroom, but the special camera gives our hero a crucial edge in the ensuing shootout, during which the entire tiled facility is reduced to smoking rubble.

"The bathroom scene was done partly with KinoFlos set on a flicker generator, which is not the healthiest thing you can do with a KinoFlo ballast," Carpenter recalls. "We found that we were going through KinoFlo ballasts very quickly, but Jim wanted the effect that one light in the room was malfunctioning from the beginning of the scene. The site of the shootout had to be lit to a level where we could sup¬ port shooting up to at least 120 frames per second for some of the action sequences. I had 2Ks pointing down through some slots in the ceiling to build up the overall stop to the T4 that I needed for the various camera speeds, which included 22,40,60 and 120 fps. In addition to the KinoFlos, we had some standard units built into a lighting fixture directly above Arnold, because we knew that some of those would have to be shot out. After the units get shot out, the electrical system goes haywire, and there's quite a bit of stroboscopic flashing to add to the excitement. We cut a hole in the ceiling just big enough to stick a Lightning Strikes! unit down through the hole, which was hidden by a room divider; that's what gave us the variable flicker effect. We would tilt the light one way or the other, depending upon which section of the bathroom we were shooting in. I also knocked the light down a bit by putting 10K scrims in front of the unit.

"Jim wanted to get a ton of coverage for that sequence, so we were constantly moving smaller units around to edge and line the action. Ninety percent of the lighting was coming from the ceiling, but often, in order to pick out certain things visually, I had other units hidden where the camera couldn't see them. For the shot where one of the bad guys comes at Arnold with a knife, we had lights coming from the other room to highlight the spraying water and to edge the bad guy. This technique involved a constant cat-and-mouse game between Jim and me; I'd run a unit in and he'd say, 'No, no, no, the camera's going to pan over there, pull that unit out.' Or it would work the other way; when I thought I couldn't work a unit in, Jim might say, 'How come you're not lighting this?' We were always trying to guess which way the action would go."

Having eliminated two of his three pursuers while destroying the bathroom, Harry chases the group's ringleader, Aziz, out of the hotel and through the streets of D.C. After exchanging gunfire with Harry and the waiting Gib, the terrorist seeks a quick escape by commandeering a motorcycle. Undeterred, Harry knocks a police officer off his horse and gallops after Aziz, who accelerates right back into the hotel. The pair careen through the hotel's hallways, then race to the top of the building in separate outdoor elevators. Aziz eventually eludes capture by executing a stunt that would discourage Evel Knievel himself, rocketing his cycle off the roof of the hotel, across a precipitous gap and into the swimming pool of an adjacent hotel.

"The horse and motorcycle chase is one of my favorite sequences," Carpenter says with a grin. "Basically, you're dealing with a sequence that was shot over six or seven locations, and they all needed to tie together. The beginning of the horse and cycle chase was staged in Franklin Park in D.C. It was very difficult to shoot, because when we first scouted the location we thought we'd simply use the Muscos to light everything. Being the non-Easterners that we are, we said, 'Well, when we get back here in November, the leaves will be gone and we'll be able to shoot the lights down through these trees.' But every damn leaf stayed on those trees, and it was very hard to light the park sequence from overhead. We had to wire the park and light much of it from the ground, with small units hidden behind trees, with 1200 and 2500 HMI Pars up in the trees, and with lights simulating practical light. It was a rigging gaffer's nightmare. As Arnold was chasing the cycle on the horse, we had a light on a camera car out in the street, tracking along and providing illumination to edge the characters' faces."

The hotel footage was shot at two main locations: the Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles, and the Ambassador Hotel, an L.A. "movie hotel" in which most of the stunts were staged. In order to lend the Ambassador an elegant feel, Carpenter and his crew taped individual KinoFlo tubes to the side of vertical pillars in the hallways. "The camera angle was so wide and so low that lighting from the ceiling was definitely out of the question," he says. "We also put 2Ks and 5Ks on the floor to line and accent certain groups of people or sections of the action."

Carpenter singles out Steadicam expert Jimmy Muro for his invaluable contributions to the sequence. "We rehearsed the horse until he knew what he had to do, but wasn't bored with it. We had a limited window on how many takes we could do, and usually only managed about four. It really helps to have someone as good as Jimmy, who can make those on-the-spot framing decisions when you're working with an animal who's not going to hit the mark every time."

In order to protect the hotels' floors and allow the horse better footing, the crew lined the hallways with special padded carpeting. "Since the Ambassador is a movie hotel, we could do whatever we wanted there," notes Carpenter. "But when Arnold and the horse first come in off the street, they're in the real hotel. Occasionally the horse and the stunt rider would miss a turn and knock a chunk out of a pillar. We were constantly paying for the repairs."

Carpenter's biggest practical dilemma was matching footage from the two hotels. The Bonaventure is a more modern edifice than the elegant Ambassador, and it also demonstrated what Carpenter describes as "tremendous light-sucking capabilities. We had to run miles of cable and work at several different levels to light it up; it has five floors just in the lobby area. We put sea pars in the fountain, and wherever we could we'd put big 5Ks or HMIs around corners to edge Arnold and the stuntman. We had special lighting built into the elevators; we used KinoFlos because they don't use much power and they put out a lot of light. We also edged the elevators with special twinkle lights for added visibility."

Lighting the hotel's interior was difficult, but things got even more complex when the chase reached the hotel's tinted-glass elevators, which run up along the Bonaventure's exterior. "For the elevator ride up, we had a rubber horse that was operated by a guy inside while Arnold or a double sat on top," Carpenter says, shaking his head in amazement. "He could make that mechanical horse do some incredibly lifelike movements. One of my happiest shots of the movie is an exterior shot from the top of the building, with the bad guy in one elevator and Arnold and the horse in the other. You'd think it's either a miniature or some special process, but it's just a regular production shot. The nightmare there was that the Bonaventure is a black building with black glass. We went around to as many rooms as we could and installed practical high-intensity bulbs in practical lamps to get some detail. Then we shone a mini Musco into the side of the building to pull up the basic exposure on the elevators, and to bring out the rib-like structure of the building. The catch was that wherever you put a light to illuminate the building, you'd see it in the glass. And whenever the camera moved, the reflection would bounce off a different facet of the glass. I spent several pre-production hours walking around the building, and eventually found a spot where I could put the light so it wouldn't show up. As a final touch, we put a major Musco down the street to light up the other buildings in the area, which added even more texture and detail by creating reflections on the Bonaventure's surface. The whole thing was shot with a Lenny arm hanging out over the very top of the building."

The hotel's "rooftop" was actually a set built in an aircraft hangar at California's Van Nuys Airport. "Base lighting was done from the ceiling because of the reflective surfaces," Carpenter notes. "We hung a lot of chicken coops to build up our ambient light. We also hung up a massive TransLight of the Washington area. We had to pay special attention to sags and folds that gave away the fact that it was a TransLight. That wasn't our only problem, though: the TransLight was put together in vertical slits about six feet wide that were glued to each other. They started to come apart during the shoot, and it became a real mess dealing with Washington falling apart in the background."

All of the downward shots in this sequence are actually digital composites, including the view of the street beneath the motorcycle as it leaps across the void. "The jump off the building was maybe 30 feet onto a ramp that was covered with green material," Carpenter reveals. "We shot footage of a real pool at Warner Hollywood. As we filmed the plate shot, which was taken by a distant camera on scaffolding, we were also shooting live-action footage at ground level. One of the joys of working with Jim is that he's going to extract as much footage as he can from each sequence; you just have to be aware of that and light for a lot of different purposes at the same time."

The cinematographer found himself improvising yet again at California's Hansen Dam, while shooting a sequence in which Harry and Gib humiliate Helen's would-be suitor, a used-car salesman with a penchant for tall tales. "Jim wanted to start the sequence on a tight shot of actor Bill Paxton and then widen very quickly to reveal a towering overhead shot of the entire situation, with Harry and Gib interrogating Bill near the dam's edge. Because we were on a ledge, there was no place to put our lighting for the extreme wide shot, so we had to light the closeups with a major Musco that was at least half a mile away. That was our key light; our fill was coming from another Musco light parked on the other side of the dam's spillway and hidden behind a building. The problem for me was that the [lighting! ratios didn't work out quite the way I wanted for the high overhead shot. When I came down for the low shot, the shadow of the camera was being thrown across Bill's face. So as we did the shot, both Muscos altered their lighting values — one panned on and the other softened. Necessity and fear make you do strange things. Later in the sequence, of course, we came in with lights we could control, because we were just shooting close-ups."

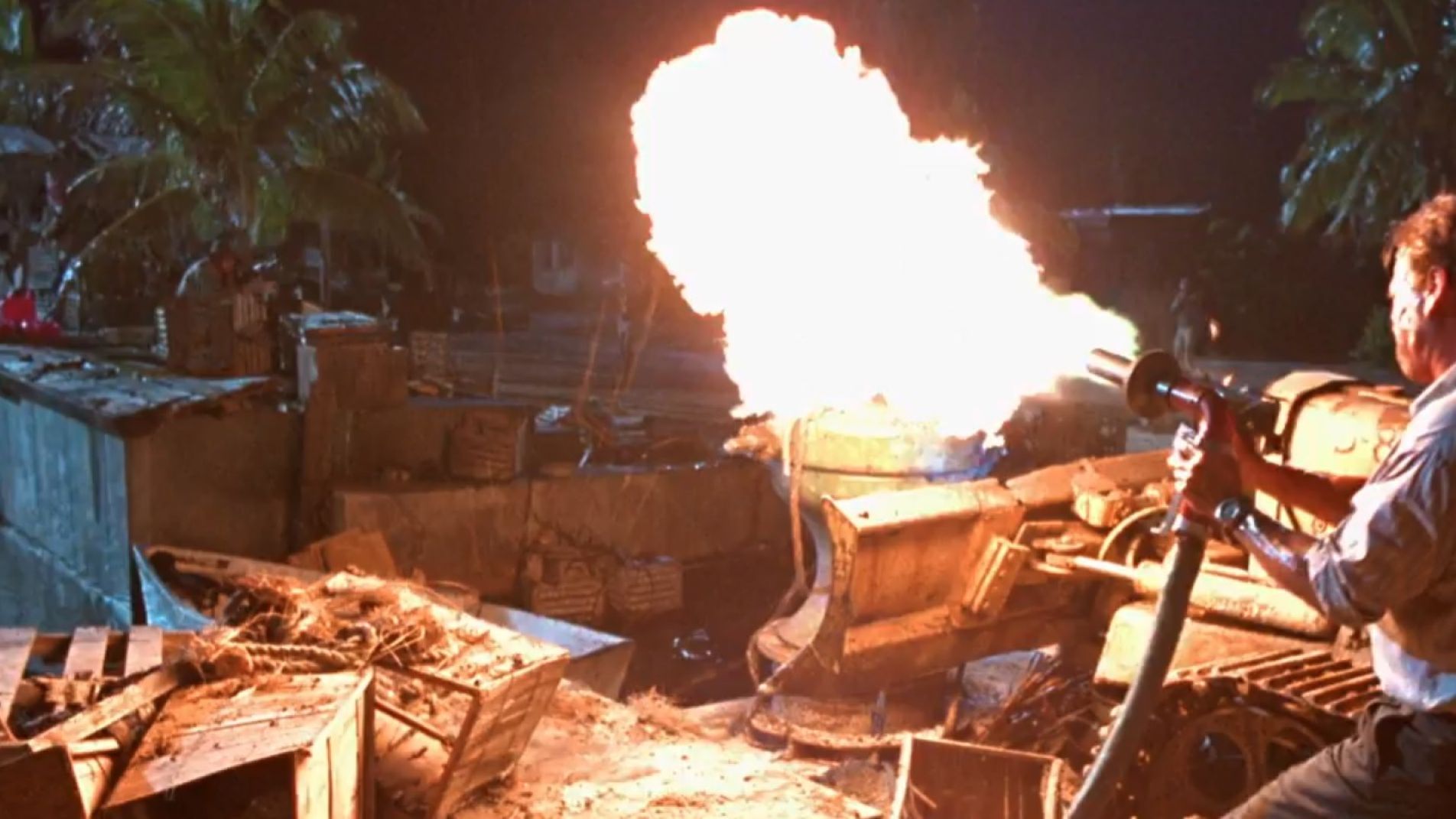

When the story's action reaches the terrorists' makeshift compound in the Florida Keys, the few remaining photographic limits are all but obliterated. Harry and Helen are held captive, but Harry eventually manages to escape amid a hail of bullets and explosions. The entire compound sequence is a virtual primer on film pyrotechnics.

(Jamie Lee Curtis) have a heart-to-heart about the state of their marriage.

"One thing I learned while shooting Hard Target is that if you're running several cameras at varying angles, it's inevitable that a few of those angles will be flatly lit," Carpenter relates. "But whatever looked flatly lit one second will look beautiful as soon as the explosion happens. So the explosions on True Lies lit themselves to a certain degree, although we tried to build up our ambient light so they wouldn't white out. We lit the entire set, which was about an acre in size, to about a 5.6, using two full-sized Muscos and a Night Sun."

Cameron explains that his approach to pyro scenes — such as the shot in which Schwarzenegger deep-fries some terrorists with a flamethrower — was developed while shooting Aliens. "The stuff I shot with flamethrowers in that film was too blown out," he admits. "In this picture, we wanted saturation in the pyro scenes, so we lit the set to balance the flames. You could never do this kind of stuff on a low-budget movie; you'd have to blow stuff up, let it go white and try to print it down. But then your backgrounds wouldn't balance; the only thing lit in the shot would be the fire."

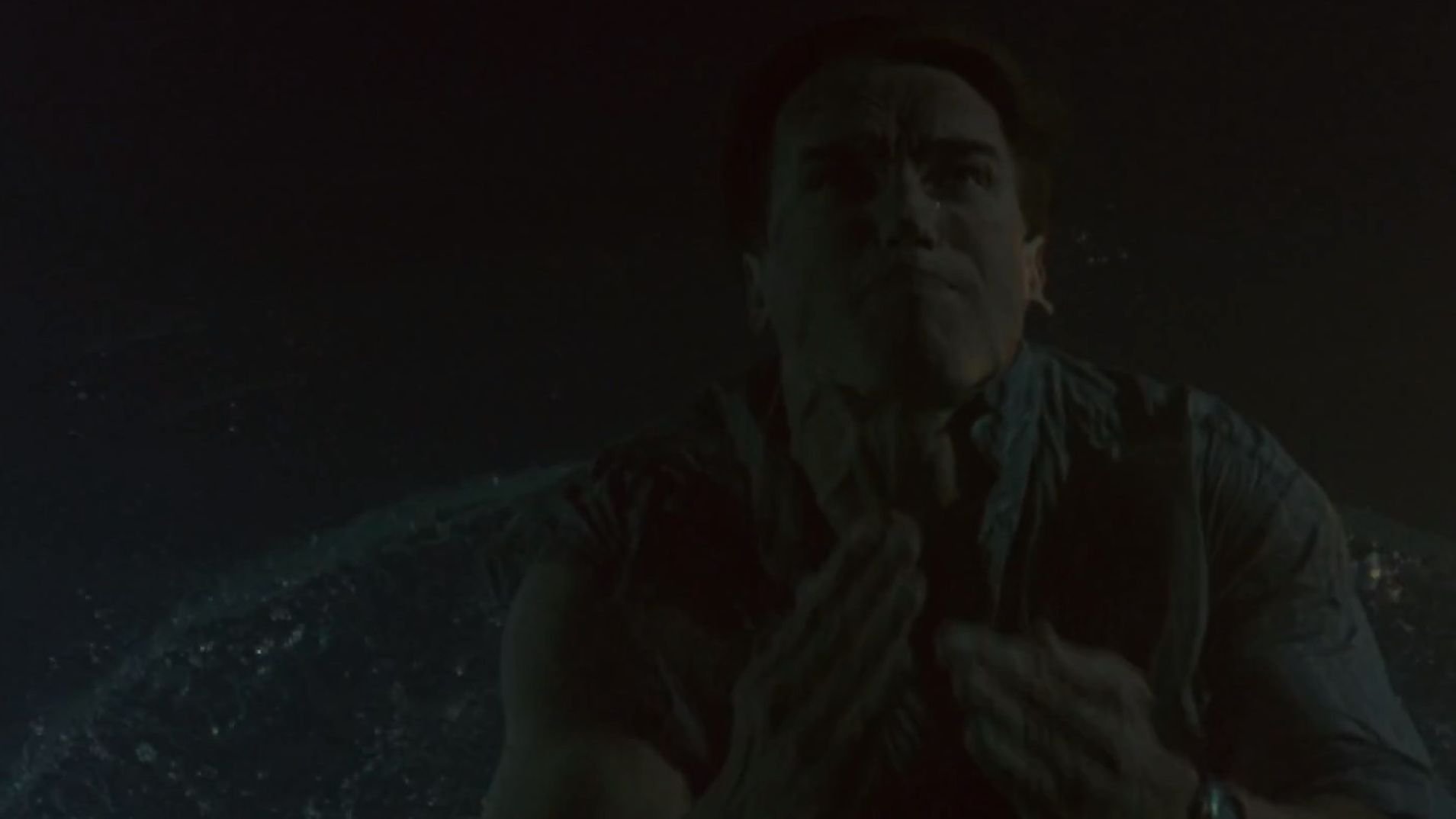

As impressive as the flamethrower footage is an underwater shot in which Harry, having leaped just clear of a fiery blast, must swim to safety beneath burning waves. Recounting the shot, Carpenter tips his hat to Schwarzenegger, who performed the stunt himself. "That shot was done in a tank in San Diego. Completely controllable flame bars were built three inches over the water, and there were safety people just off camera. We had supplemental lighting underwater so Arnold wouldn't turn into a silhouette; we wanted the audience to see that he'd done his own stunt. The flame bar didn't extend too far, and we knew Arnold could swim past it and come up safely on the other side. He was hooked up to a hydrophone so we could hear him, and if he ran into trouble we would have killed the flames instantly."

The imagery gets even wilder during the film's penultimate climax, in which Harrier jets and a helicopter attempt to intercept the terrorists' nuke-laden trucks as they traverse Florida's Seven-Mile Bridge, a section of the Overseas Highway that spans several of the keys south of Florida. "The highway sequence was a logistical horror," Carpenter recounts with a weary grimace. "The authorities closed off a three-mile section of the bridge. Luckily, we found an old stretch of highway that paralleled the new stretch, and we did all of our major stunt-work there. There was also a section of bridge that had been removed so that boats could get through. Jim saw it and said, "Hey, let's just build our own bridge and explode it!"

The director eventually decided on a more practical approach, and the section of the bridge that explodes onscreen is actually an elaborate miniature. The wreckage of the bridge, however, was built atop a barge in Miami, floated between the existing bridge sections, and sunk to the level of the water.

The Harrier jet footage presented more headaches. On days when the jets were to be used, Cameron and key personnel met at 5:30 a.m. for a military-style briefing on safety and methods. Most of the Harrier aerials were shot with a Vector Vision system mounted in a Lear jet. The trick was to carefully gauge the velocities of the various planes: the faster speeds of the Lear jet were the slowest speeds at which the Harriers could execute combat maneuvers. "We decided to use a zoom lens in¬ stead of primes, because the Harriers could only fly a limited number of missions per day, and they were incredibly expensive," Carpenter relates. "Digital Domain did some remarkable enhancement of the footage to bring it more in line with the look of prime lenses. The drawback of the expense and the potential danger was slightly degraded resolution, but Jim decided to err on the side of safety."

The highway sequence also involved a substantial amount of rear-screen work, which provided background views from the helicopter, the terrorists' vans and a limousine in which Helen and Juno Skinner engage in a backseat brawl. "I'm really proud of how well the rear-screen stuff turned out, because there was so much of it," Carpenter says. "Jim loves to move his camera in an exciting way while shooting rear-screen shots, and maintaining realistic balances was always a primary concern. I liked to overexpose the rear-screen 'exteriors' for a more blown-out, realistic feel. The most difficult challenge was when we used a plate in which the background moved a lot and the brightness levels changed radically within the shot. There were a few scenes in which the rear-screen stuff didn't line up exactly right, but we used them anyway because the action was so good. We can only hope that the audience doesn't notice with all of the other stuff going on."

Carpenter is quick to point out, however, that the sequence's most hair-raising shot — in which Jamie Lee Curtis dangles from a helicopter some 250 feet over the ocean after being hauled out of the limo, on the fly, by Schwarzenegger — was fully authentic. Cameron shot the actress' frenzied reaction himself, from the relative safety of the helicopter's runner. "She was a real trouper," Carpenter avers in a moment of profound under¬ statement. "The cable she was hanging from was strong enough to lift an elephant, but it took real guts to go through with that stunt. I guess Jim's mania was contagious."

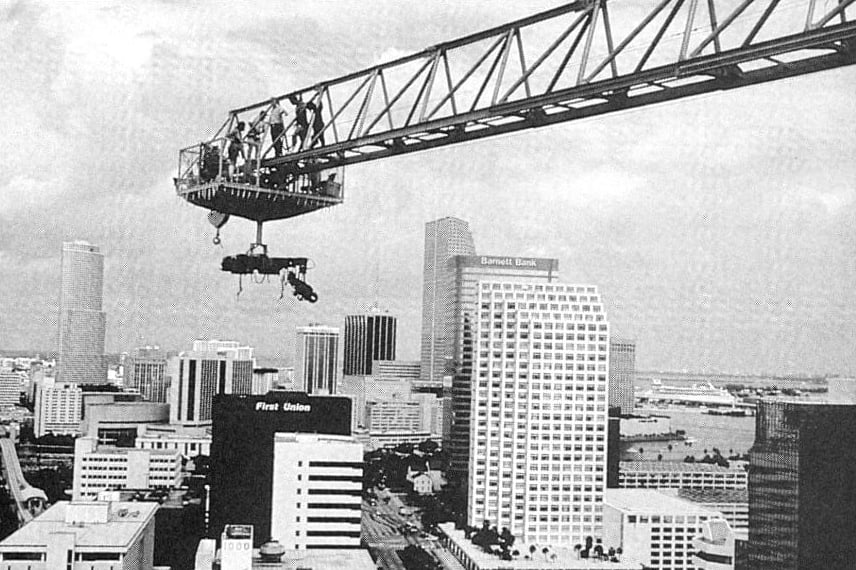

The mania reached its zenith during filming of the picture's climax, in which Harry commandeers a Harrier and at¬ tacks a Miami high-rise from which Aziz and his remaining co-conspirators are threatening to detonate the last nuclear warhead. In the process, Harry stages a daring rescue of his daughter, who has been taken hostage but helps to thwart the terrorists' plans.

To make the plane look like it was flying in the shots that weren't digital composites, a mock plane was placed on a major gimbal system that was constructed atop a 22-story building in Miami's business district. "The building had to have a small enough area on top so that you couldn't see it when we shot across the plane and down," Carpenter explains. "But that also meant that we had very little room for crew, cameras and lighting. A massive scaffolding structure was erected to support the crew around the plane, and we had to reinforce the top floors of the building to support the weight of everything. For our lighting we had a Lightmaker brute, which has the power of nine 1200-watt HMI units. For fill, we used a little Condor that had very limited movement. As for the cameras, we had a mini-studio in the air. On the perimeter of the building we had a Lenny arm with a camera on it. We used the big yellow crane you see during the climax as a camera platform, and we hung a Technocrane from it in a basket. The Lenny was operating from a level six feet below the crew, and the Technocrane could get anywhere. By cutting between those two moving cameras — one moving on an arm from below the plane, and one moving from above — we could create the illusion of movement.

"Because the weather changed so much, and because of the moving cameras, I couldn't get the lights to where I wanted them ideally. I was very often working from just below the level of the cameras and shooting fill light up into the actors' faces whenever I could. That was a tough go, because we really wanted to serve the camera movement more than the lighting in that situation. The weather was variable, and the sun was always moving, so we were trying to keep the background correct. A lot of that footage was supplemented with rear-screen projection and TransLight photography."

The sequence reaches its high point when Harry and his Harrier suddenly hover into view outside the building's windows, to the shock of the terrorists. Seconds later, he obliterates the entire floor — and the terrorists — in a fusillade of gunfire. "When Arnold shows up outside the windows in the plane, he's in front of a huge TransLight backing on a stage. There were lots of imperfections in the TransLights, so we helped it as much as we could with the lighting, and Digital Domain smoothed everything else out later. The plane itself was on a hydraulic lift.

"The later scenes in which the plane crashes into the building were also done on stage. I tried to overexpose the TransLight as much as I could to take the curse off the fact that it was a backing. The window glass had a three-stop exposure loss, so I was also trying to find an expo¬ sure level that would serve the shot before the glass breaks and then also work for the shot after¬ wards, when you've got three stops of hot light coming in. Luckily, that sudden burst of light dramatically served the purpose of the story.

"The shot of the plane shooting out the windows was a miniature, and it was combined with interior and exterior shots that were done on a stage," he concludes, a bit winded from the discourse.

Looking back on his trial by fire, Carpenter is quick to praise the efforts of his crew, who toiled beside him every step of the way. "On a project this huge, you need the talents and support of a lot of people. I had to rely upon the crew and the rigging people to a large extent, because they'd seen the sets before I had," he notes. "I'd like to salute a few guys in particular: rigging gaffer Steve Cohagan; gaffer Rick West; key grip Lloyd Moriarty; B camera and Steadicam operator Jimmy Muro; operators Michael St. Hilaire and Paul Babin; and focus pullers Mark Jackson and Chris Moseley. These people were constantly thinking about potential problems and bringing them to my awareness. What got us through the day, though, was knowing that Jim would do whatever it took to realize the movie without compromise. When you have that commitment from the director, you know that you're in good hands. We all had to cross the Himalayas together."

For his part, Cameron remains, as always, an unrepentant adrenaline junky. He maintains that he felt no special pressure to outdo himself after the mega-success of Terminator 2, or to make people forget the box-office failure of The Last Action Hero, which also combined action and comedy. “I just keep doing it the way I do it and hoping that people will respond to different material and different characters," he says. "When your usual method is to run with the hammer down at all times, you really can't change; there's no headroom! I've been giving 100 percent since the first Terminator film. To me, the process would not change even if I did a smaller picture. Some days on this film, I went in and shot a little, quiet dialogue scene with a few closeups and a couple of laughs. On other days, we'd go in and shoot two Harrier jets and a helicopter landing on a bridge. And anybody who says they're not twisted up in a knot before a day like that is a sonofabitch liar. No matter how many times you do big stuff, you're always apprehensive, because you have a great responsibility to get the work done safely."

"But then again," he concludes wryly, "if the shoot's not exciting, the film's not going to be exciting."

Carpenter was invited to join the ASC in 1995 and honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2018.

For more on his work, check out these pieces on Titanic, The Calling, Jobs and Avatar: The Way of Water.

Second-unit cinematographer Shelly Johnson was later invited to join the ASC as well, and his credits include Jurassic Park III, Captain America: The First Avenger and the World War II drama Greyhound.