Extraterrestrial Escapades: Men in Black

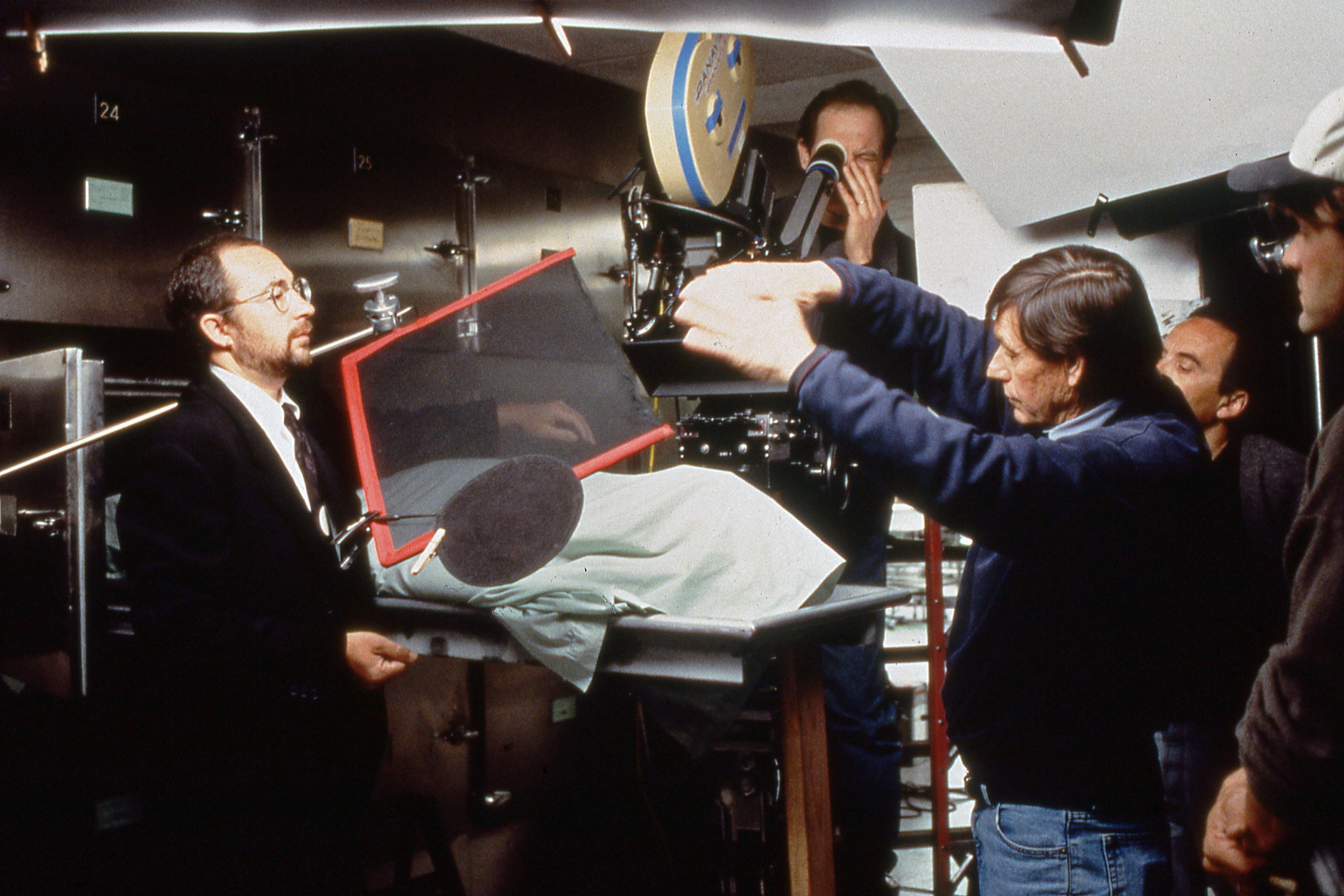

Director of photography Don Peterman, ASC helps give the term "illegal alien" a humorous twist in this sci-fi comedy.

This article was originally published in AC, June 1997.

Unit photography by Melinda Sue Gordon and Andy Schwartz, courtesy of Columbia/Tri-Star

Asked to describe his role on director Barry Sonnenfeld's science-fiction farce Men in Black, cinematographer Don Peterman, ASC replies with a chuckle, "It was a big job."

The duo had previously collaborated on the comedies Addams Family Values and Get Shorty; Peterman was first asked to shoot MIB while doing retakes on the latter film in late 1995. Though the cinematographer previously photographed fantastic beings in Splash, Cocoon and Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (earning himself an Academy Award nomination for Trek), MIB's multitude of alien characters would soon make him a virtual expert on xenomorphs.

A native of Hermosa Beach, California, Peterman began his career as a loader and assistant in the opticals department at Cascade Pictures, the same commercial house where special effects pioneers Dennis Muren, ASC and Ken Ralston also got their starts. The cinematographer's other feature credits include Flashdance (which also earned him an Oscar nomination), When a Stranger Calls, Rich and Famous, King of the Mountain, Young Doctors in Love, Kiss Me Goodbye, Best Defense, Mass Appeal, American Flyer, Gung Ho, She's Having a Baby, Point Break, Mr. Saturday Night and Planes, Trains and Automobiles.

Based on the cult comic book The Men in Black by Lowell Cunningham, MIB's premise will seem familiar to even occasional viewers of The X-Files. Known only by their initials, dark-suited MIB agents K (Tommy Lee Jones) and J (Will Smith) are part of a top-secret Federal bureau that monitors interstellar immigration. Their job: to keep their fellow Earthlings in a blissful state of ignorance by concealing the identities and activities of the nearly 1,500 aliens that live among us — mostly in Manhattan.

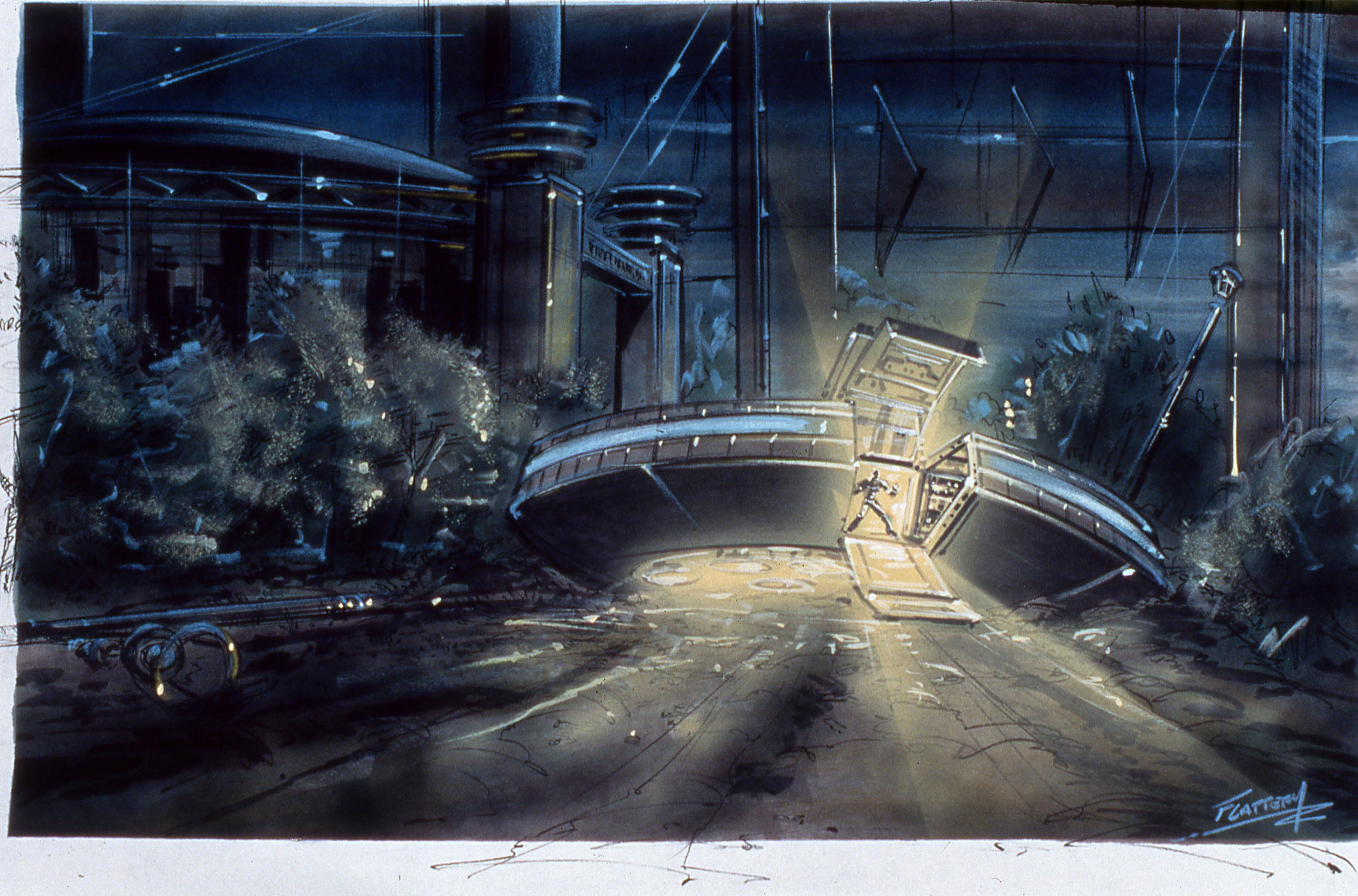

While investigating an unauthorized visitation, K and J uncover an intergalactic terrorist plot to destroy the Earth. Their nemesis, known as Edgar when disguised in human form (Vincent D'Onofrio), is actually a three-meter-tall, roachlike insect. The Ray-Ban-wearing duo eventually confront him in a showdown at the now-decrepit site of the 1964 World's Fair in Flushing Meadows, New York.

“There’s a certain mindset you have to have on an effects film like MIB in order to piece everything together and have a complete image of the film in your head while you’re shooting."

— Don Peterman, ASC

The picture was complex on both photographic and logistic levels; Peterman had to deal with complicated special effects issues (physical, makeup, mechanical and digital) throughout MIB's 17-week production. The cameraman recalls, "Fortunately, we had a nine-week prep period. We needed that time because there was a lot of New York location shooting scheduled in between our stage work at Sony Pictures in Los Angeles. Naturally, things changed all the time, such as deciding where to shoot certain scenes and where to build the sets. Until we started shooting, we didn't know whether we were going to do the night exteriors on location at Flushing Meadows or on a stage at Sony. We finally wound up building a big set on stage."

In fact, two key exteriors were constructed at Sony: Flushing Meadows and a desert along the U.S.-Mexico border. "There are so many effects in those scenes that to work in either New York with short nights or out in the real desert would have been impossible," says Peterman. "Starting in March of 1996, we shot the opening desert sequence and the MIB headquarters scenes at Sony. We went to New York in May and finished a lot of night exteriors in Manhattan. Then we then returned to L.A., where we'd also done some exteriors up in Simi Valley, and finished shooting on the Flushing Meadows stage, which we had prepared for while doing location scouting in New York."

Much of Peterman's prep was also spent with visual effects supervisor Eric Brevig of Industrial Light & Magic. "We mostly discussed when to use VistaVision, what stocks to use, and when we could get by just using 4-perf," the cinematographer says. "We also discussed angles, lenses and all that — with Barry working shots out ahead of time so ILM could match our stuff when they got into shooting miniatures and doing other effects work."

Peterman feels that the constraints imposed upon cinematographers by visual effects techniques have lessened radically since he shot the films Cocoon and Star Trek IV. He recalls, "Way back, when I was at Cascade, I did optical printer lineup and was trained to do effects work. All of that experience is now out the window because of computers, but I understand the concept of compositing layers of images — although I certainly never sought out special effects pictures because of my background. My agent had to talk me into doing Star Trek IV, which was a great experience and ultimately helped me in terms of dealing with the types of complex effects we had on this film. There's a certain mindset you have to have on an effects film like MIB in order to piece everything together and have a complete image of the film in your head while you're shooting."

Asked if working with Sonnenfeld, who was a highly regarded cinematographer before becoming a director, added an extra degree of difficulty to his work on MIB, Peterman offers, "Not at all like you'd think. When Barry asked me to do Addams Family Values, he said, 'I don't have to get involved with the photography, and I don't want to worry about the photography — I've got my own problems as the director.' He is very hands-off as far as the lighting, angles, or anything else is concerned, but he does like to pick the lenses, and they're going to be wide lenses. Barry always used wide lenses on the movies he shot, such as Raising Arizona and Blood Simple. He'll usually choose a 10mm, 14mm or 21mm, and he likes to shoot close-ups with a 27mm.

"Barry's philosophy is that you have to be in here with the camera to shoot a close-up," Peterman elaborates, gesturing to within a few feet of his own face. "Otherwise, the shot just doesn't ring true in his head. But of course when you do close-ups with such wide lenses, the subject can never actually look at the other actors. The distortion makes it seem as if they are looking in a completely different direction, which ruins the eyelines. To correct the problem, the cameraman usually puts a little piece of white tape right next to the lens, and the actor has to look at that during the shot.

"But Barry's an ex-cameraman, so we can get into all of that. I get along really well with him personally, I know his style now, and I think his approach has been the right one on all three pictures we've done together. Each is kind of bizarre and throws its comedy right in your face."

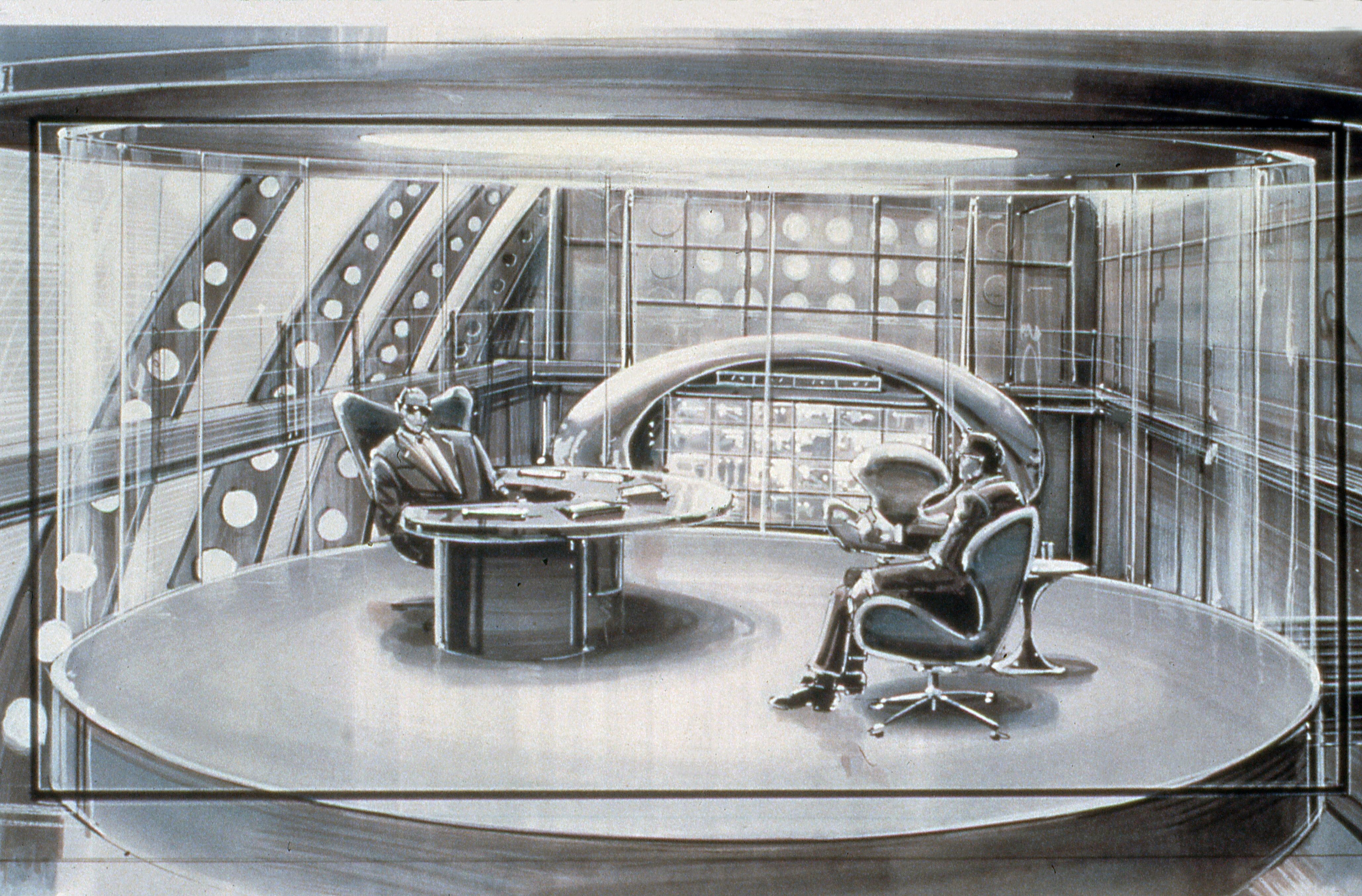

During AC's visit to Stage 15 on the Sony Pictures lot, it quickly becomes apparent that something funny (as in peculiar) is going on. Constructed within is the centerpiece of the film, the MIB headquarters — a retro-futuristic, airport-like customs area with one long curved wall consisting primarily of brightly backlit material. Dominated at one end by a huge, Jetsons-esque oval viewscreen, the immense oblong room is filled with decidedly unearthly things. Strange, chrome-plated instruments and weapons line special cubicles; one corner is filled with a voluminous glass container holding an overgrown brain floating passively in green-tinted fluid; on the far side, a pair of multi-limbed octopoid creatures operate twin control consoles.

"A lot of our prep period consisted of meetings on the rigging for this and our other two main sets.”

Fortunately, Peterman soon arrives to make sense of it all. "A lot of our prep period consisted of meetings on the rigging for this and our other two main sets," he says, leading the way out and around the structure. This stroll reveals an elaborate latticework of pipe scaffolding and 20K fixtures behind the room's translucent wall, which essentially makes the MIB complex a giant softbox. "We have 300 lights on this set alone, because we lit it for Kodak's 5248 stock. There are a lot of digital effects that will be added later, but with that stock, we could shoot in 4-perf with our Panavision cameras for most of the work in here instead of going to VistaVision." Both the Panaflex and Beaumont VistaVision cameras were operated by Stephen St. John, who also served as Steadicam operator on the show.

"Because of the depth of the headquarters set, we needed at least a T2.8 1/2 so the background detail wouldn't go mushy," Peterman adds. "Shooting with 100 ASA stock, which I was rating at 80, I spent a lot of time with my gaffer, Jeff Murrell, and the electricians figuring out how to use enough light to get that stop without burning the place up." This requirement, coupled with Sonnenfeld's penchant for both wide lenses and a 1.85:1 frame, also led the cameraman to integrate lighting into the set whenever possible.

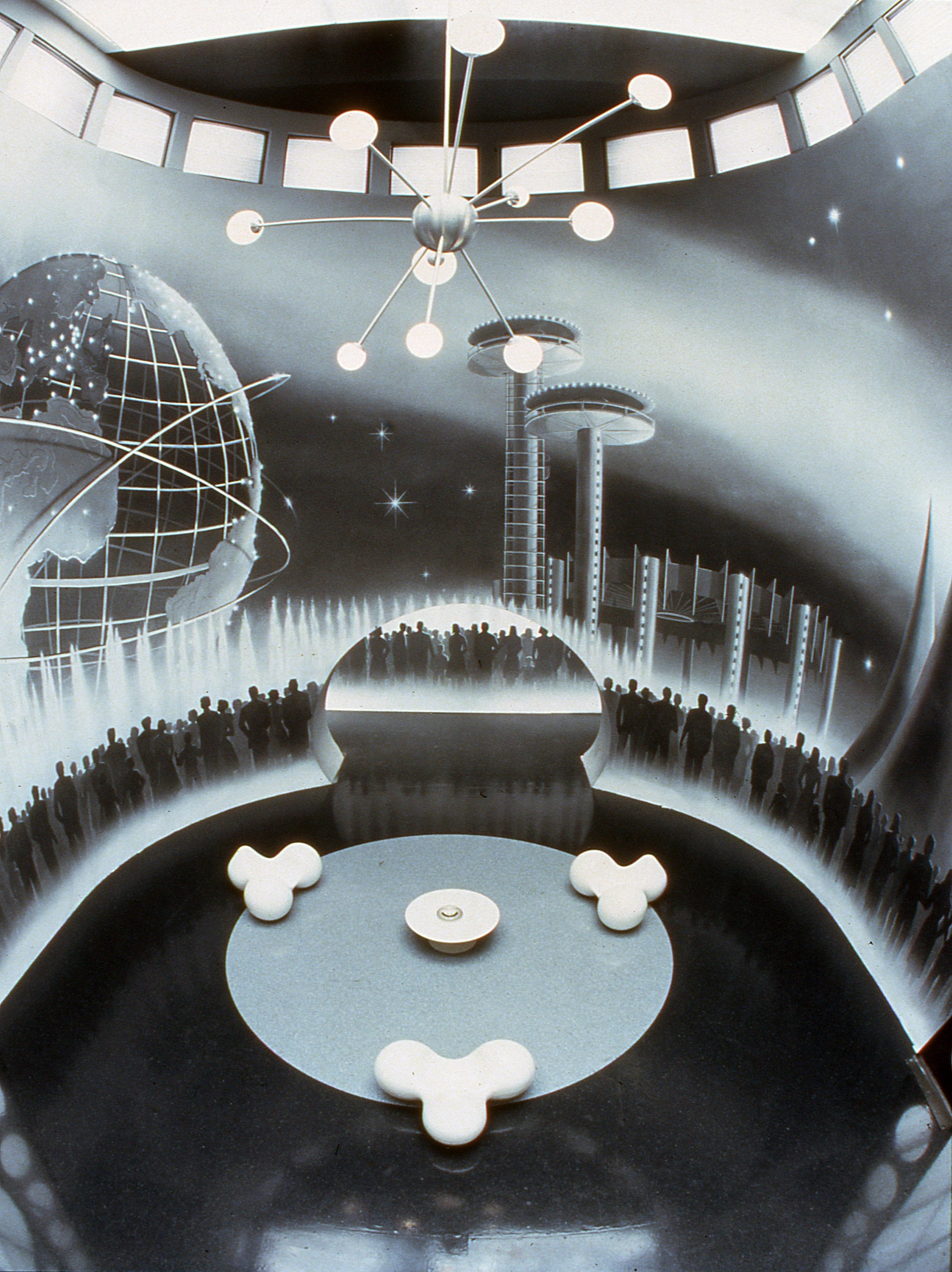

The MIB headquarters was contrived by production designer Bo Welch, whose credits include Beetlejuice, Ghostbusters II, Edward Scissorhands, Batman Returns and Wolf. "The script had some background about the Men in Black organization, which was supposedly formed in the 1960s," says Welch, who has since moved on to design the political satire Primary Colors. "I suggested to Barry that their headquarters should be sort of an Ellis Island for aliens, as designed by a prominent architect — who then had his memory conveniently erased."

Toward that end, Welch studied the work of Finnish architect Eero Saarinen, the designer of TWA's terminal at New York's John F. Kennedy Airport. "The vocabulary of shapes and materials that Saarinen used evoke a sense of space travel and an unbridled optimism about the future," Welch offers. "It would have been too obvious and clichéd to make the set shadowy and dark. I saw the Men in Black headquarters as a central, bureaucratic office; all of the government offices I've ever been in are places where you can see things. People work there. So my first idea was to create a sterile, clutter-free space and integrate this enormous light-wall into the design. Both people and the aliens would stand out well against that kind of background. It was also interesting to have a set that was nearly pre-lit with the flick of a switch."

"It would have been too obvious and clichéd to make the set shadowy and dark. I saw the Men in Black headquarters as a central, bureaucratic office; all of the government offices I've ever been in are places where you can see things.”

— production designer Bo Welch

Home to the cynical, cloistered MIB, Welch's open, almost playful design also adds yet another touch of ironic humor to the picture. Peterman explains, "We covered the light-wall with 1000H tracing paper, which is pretty thick, but the light coming through is a lot softer. I didn't want any shadows on the wall. I wanted it to burn out, so when people walked in front of it they'd become silhouettes. So while I used fill and other lighting effects in different parts of the set, the whole room was basically lit through this one wall."

Due to the intensity of the light coming through the paper, however, additional steps had to be taken while shooting with the wall behind the camera in order to avoid any flattening. Explains Peterman, "I usually backlit the actors to create a rim on them, cut the front down, and then cheated them a little bit so they wouldn't be so flat. That was the biggest obstacle. I also had trouble with the big pieces of stainless steel and chrome detail built into the set. They kept flaring out, so we had to do a lot of dodging with black 12' x 12's to dull them down and keep the light from blasting back into the lens."

This overall lighting approach also generated a substantial amount of heat on the set. As Peterman relates, "We had about 40 20Ks hitting that paper on the wall, which can get us up to about 160°F in the ceiling area. That caused the sprinklers to go off once when we were pre-lighting, but it wasn't a disaster. We ended up putting some fans up there. The only other problem we had was that Bo made the framework for the wall with this plastic tubing, which we put our paper over. Well, the heat can cause the tubes to warp a bit, but we were able to fix that at night when necessary.

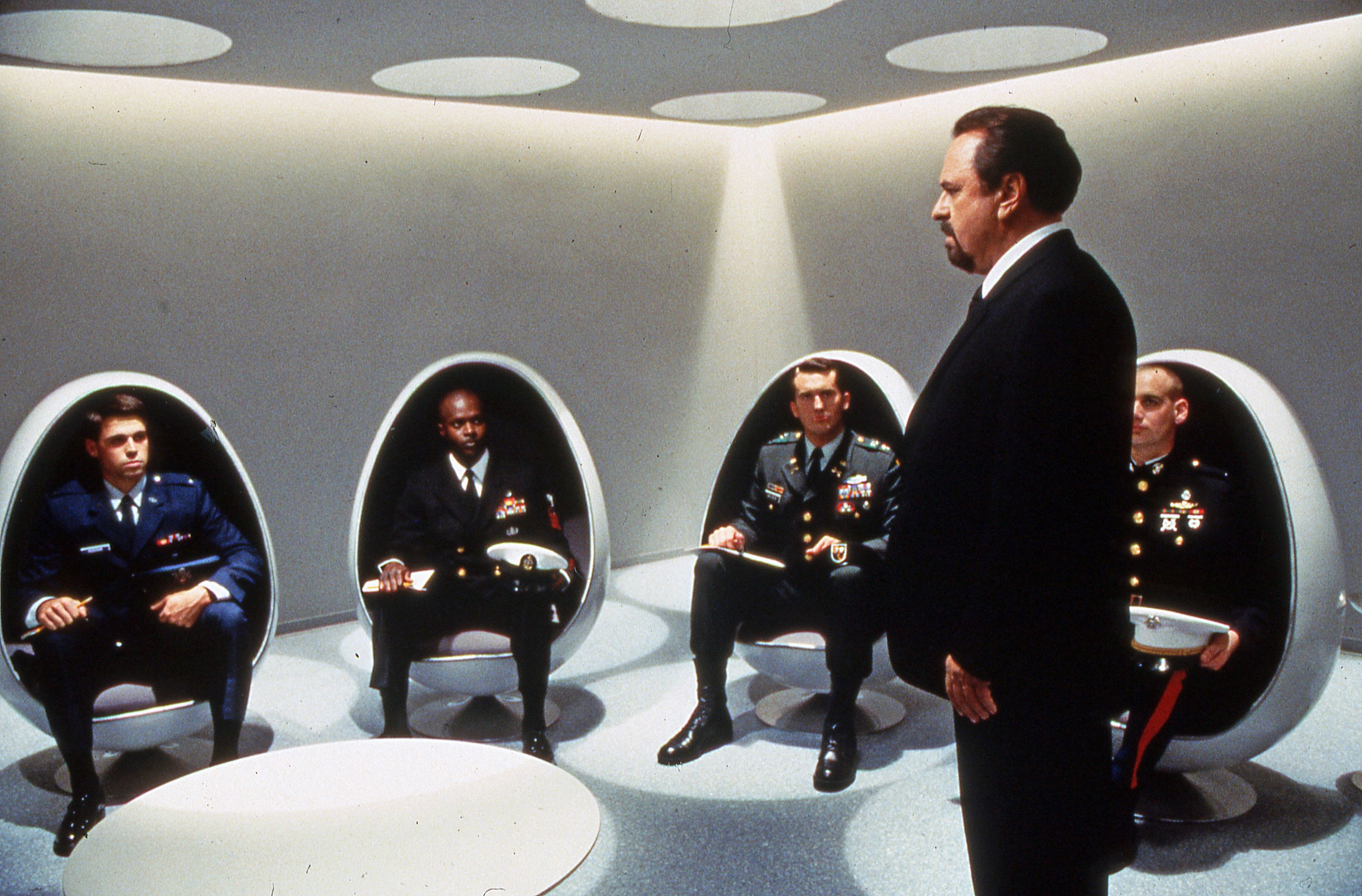

"Working with Bo is great because he creates opportunities so you can figure out what kind of lighting will work best," Peterman attests. "The lighting he imagined is very graphic, using certain shapes throughout the set. For example, there are a couple of scenes where the characters are walking down these long hallways. The lighting is built into the set as circles and lines. It's an architectural lighting dream. The halls have these 8'-wide circular skylights cut into the ceiling every 10 feet, but Bo only gave them an 8' ceiling, so these lights are right on top of the actors. Spaced out properly, they add depth and drama as people walk through them. We covered the openings with muslin and then backlit them, which created these glowing soft circles.

"Bo then had these lines of fluorescent tubes built in the walls, just along the floor, which added to the sense of perspective."

Says Welch, "It's incredibly important to integrate lighting into the design of any set, and Don was the first person I asked about certain ideas to see if they were beneficial, good-looking and doable. Those circular skylights also carried over the circle motif that I used throughout the set and the rest of the film. Circles are very futuristic and suggest all kinds of things. I really wanted the audience to imagine those skylights to be flying saucers zooming over people's heads as they walked through those corridors."

This motif was echoed throughout the various sets built to create the MIB lair, including a small room in which new recruits are tested by the agency's gruff chief. Again, the ceiling featured circular skylight openings but "instead of the muslin and diffused light, we used very hard light. From up high above the openings, I used super-hard Fresnels, so the shafts project down to make these hot, crisp-edged pools. I might have liked the effect better if they were little hotter, but to get each pool to overexpose further I'd lose some control because the lights would have to be up higher and be so much brighter. Also, because we had 25 or 30 of these circles to do, it was impossible to overexpose that much. There was just too much ambient light.

Noting the main hall's cool, institutional lighting, Peterman says, "We started out with it looking much colder. But Barry isn't really big on blue and neither am I. It's been overused and is becoming kind of a cliché. We did some tests and decided to up warm it up in the printing stage. I didn't want to have to change the gels on all of these lights! But the cool feeling is also appropriate for the room — it's a government workplace.

"To create some contrast, we also have these little halogen desk lights that we bring up really high. They're so hot that we can only turn them on just before we roll. They're about 3200°K, while the rest of the room is around 3600°K. I tried to get them about two stops over, to roughly T5.6, because I wanted the color to change on the desks, spilling onto the wardrobe and the hands of the people sitting there."

In the end, Welch and Peterman's approach to the MIB headquarters set helped keep the production on schedule. "We didn't spend a lot of time relighting," he says. "And that's what Barry wanted. We tied up a lot of lights, but he also spent a lot of time on the set floor in order to get it smooth enough for us to dolly without having to lay down track. I had to make a lot of lighting decisions before the action was blocked out, but if we'd walked in here cold and tried to light this whole set, especially using such wide lenses, we'd never have gotten through it."

Interestingly, the Modernist themes found in the MIB headquarters and other sets designed by Welch were later echoed in location work shot at the conical Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. The production designer remarks, "The Guggenheim has the same architectural vocabulary we had already been dealing with; it looks almost like a stack of spaceships. I had been looking at it since day one, trying to figure out how it could be worked into the film. In my opinion, movies that have a visual consistency are more successful, and I thought that shooting there would definitely help create that feeling."

"There were tremendous restrictions at the museum, however," Peterman recounts. "They had an exhibit going on, so they wanted to know everything about our lights, particularly how much UV light HMIs throw out. We couldn't even put lights on certain floors. We ended up primarily using fluorescents, which they loved, and pre-rigged it all the day before the shoot.

"The Guggenheim is basically a giant incline spiral. In the scene we shot there, Will Smith runs from the ground floor to the roof, with two cameras looking straight down the center from the top — starting with a 10mm and going longer for tight shots. We attached Optima 32 tubes to the bottom of the railing, which is this solid wall to the left side of the ramp, so Will was underlit all the way up. Then I turned on their house lights and just bounced some more light off the ceiling. It's all just ambience, but the interior is entirely white and we could shoot with 5293, so we had about a T2. It's a wonderful building, so it looks great, but we were only in there for about an hour."

The Guggenheim's roof was also used in the sequence, with its permanent lighting (uncorrected fluorescents) primarily illuminating the scene, augmented by ball-shaped practical lamps.

Peterman found that another time-saver was to have very close ties to his second unit, which also kept MIB's visual style consistent. As he explains, "Keith Peterman shot second unit for me on Addams Family Values; over the course that film's 128 days of production, we developed a system in which his crew would come in immediately after we got through, and shoot all night on the same sets with the same lighting. So not only would there be continuity in the lighting between shots, but we didn't have to reorder lights. I used Keith again on MIB, and it really helped." Operating for Keith Peterman was Greg Smith.

The second unit also ran a live video feed to the first unit site so that Sonnenfeld and Peterman could have direct input on each setup if necessary. "That way, we got a much better match than if they'd had to come back a month later to try to re-create something we'd done," says the cinematographer. "Of course, Keith knows how to light the way I do. In addition, Eric Brevig directed a lot of the second-unit footage, and Barry and I had discussed a lot of that with him in prep.

"With our schedule, we would have been dead if we hadn't had a full-time second unit. But it worked so well that we were soon about four or five days ahead by the end of the first L.A. portion of the shoot. That was killing Bo Welch, because he wasn't ready for us to go in on some sets. We had his crew working overtime because we were catching up to them. But we fell behind again by going to New York, due to the short nights with the weather."

The intense, sharp-edged lighting seen in the MIB headquarters set exemplifies the film's overall clean photographic style, though Sonnenfeld also sought a gritty French Connection-with-aliens feel for certain sequences shot in Soho and in New York's meat-packing district. As Peterman says, "To get that crispness, we've generally used Ultraspeed or regular Primo lenses and very little diffusion, although I have used a little bit on the actors. We also want to make the film contrasty, with very deep blacks, so I'm overexposing a bit and printing it down.

"On dailies, we printed up around 38, 37 or 40 to crush the blacks so we'd still have good solid blacks by the time we got to the release print stage. That's also another reason why we limited the headquarters set to just a few colors — black, gray, white and flesh tones."

MIB's final timing and release prints were slated to be done at Technicolor (under the supervision of Bob Putynkowski), and Peterman's New York footage was processed at DuArt. But the cinematographer specifically requested that his dailies for the Los Angeles portion of the shoot be done at CFI. "I feel I have control there because I've built up a relationship with Art Tostado and timer Ron Scott," says the cinematographer. "When I finish shooting each night, I can call Ron up and explain what my lighting situation was and whether I want something a little warmer or colder."

Summing up his experience on Men in Black, the director of photography offers, "Because of the slow stock and amount of light we were using, the headquarters set was definitely one of the most challenging interiors I've ever done. Since my very first film, When a Stranger Calls, I've usually been [more of a low-key minimalist] in terms of lighting. I shot that one with nothing — strictly Sun Guns and bounce cards at T1.4. Once your eye gets used to looking at things that way over the years, it becomes tough to do the kind of high-key lighting we did on this film. It really makes me admire people like Gregg Toland [ASC] and Robert Surtees [ASC], who used to shoot films all the time with stock that was rated in the range of 16 ASA. Looking at films like Citizen Kane or The Bad and The Beautiful, you sometimes have to wonder how they did it."

Peterman is currently off shooting the Disney feature Mighty Joe Young, directed by Ron Underwood. A contemporary remake of the 1948 great-ape film, which relied on Willis O'Brian's stop-motion animation techniques to bring its eponymous gorilla to life, this new picture's simian co-star will be realized with animatronics by expert creature-builder Rick Baker. Shot on the Hawaiian islands of Oahu and Kauai and in L.A., the picture is scheduled to be released in the summer of 1998.

Creating MIB's Eclectic Array of Aliens

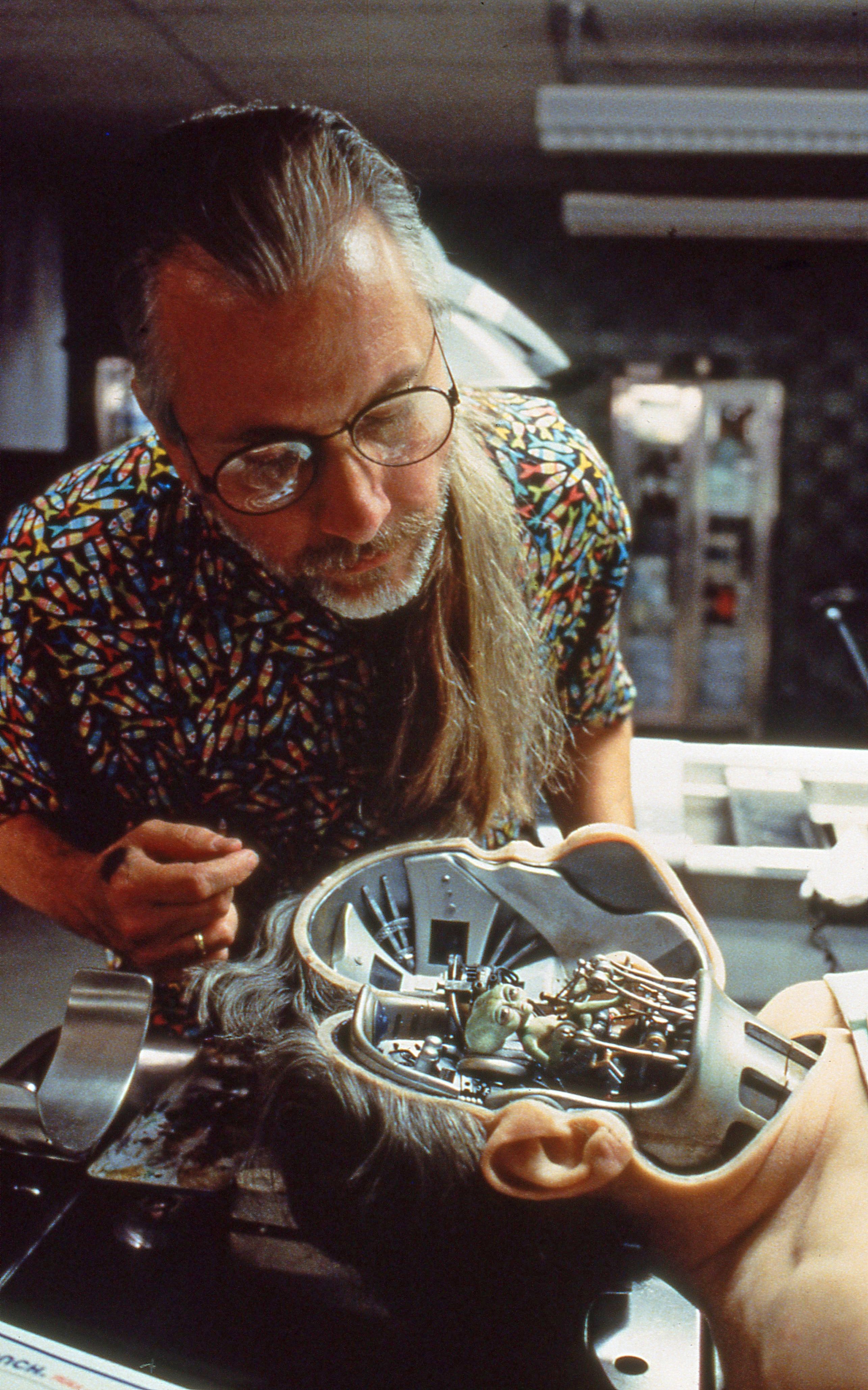

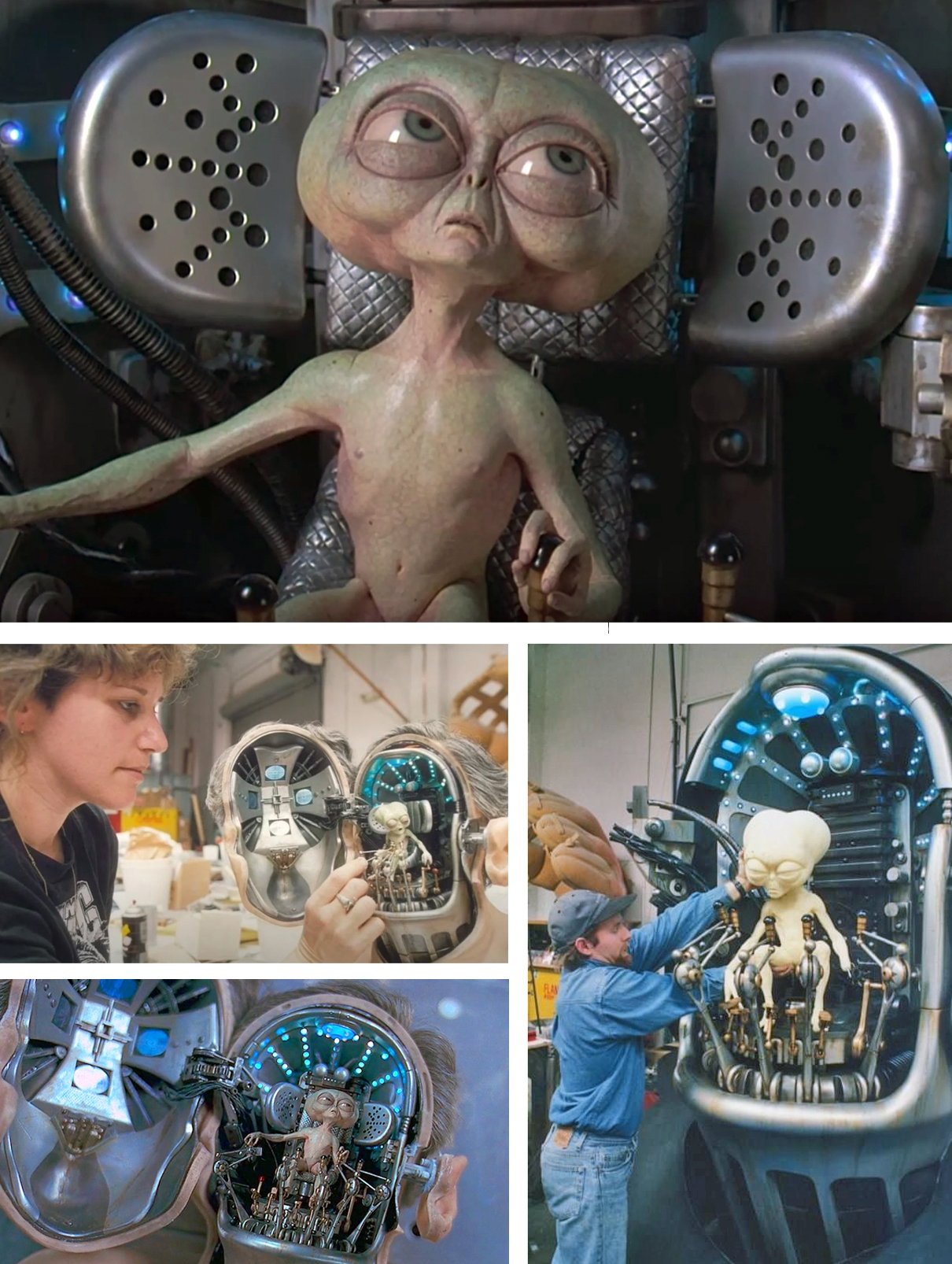

Men in Black’s multitude of otherworldly species was of realized by ace makeup effects artist Rick Baker, a recent Academy Award winner for his efforts on The Nutty Professor. But unlike his very human (if exaggerated) creations for that picture, MIB recalls Baker's spectacular creature work in such films as An American Werewolf in London, Harry and The Hendersons and Gremlins 2. In all, the artist and his company, Cinovation, created nearly a dozen distinctly different aliens for MIB, using every method available: prosthetics, rubber suits, animatronics and huge mechanical puppets.

Baker presented hundreds of alien designs to director Barry Sonnenfeld, executive producer Steven Spielberg, and producers Walter F. Parkes and Laurie MacDonald, often recombining various elements to concoct something that satisfied everyone. As Baker relates, "They rarely agreed with each other, so there was a lot of mixing and matching going on, such as, 'Steven really likes the neck on drawing A, Barry likes the feet on 3C, and Walter likes the torso on D15, so draw one that looks like that.'"

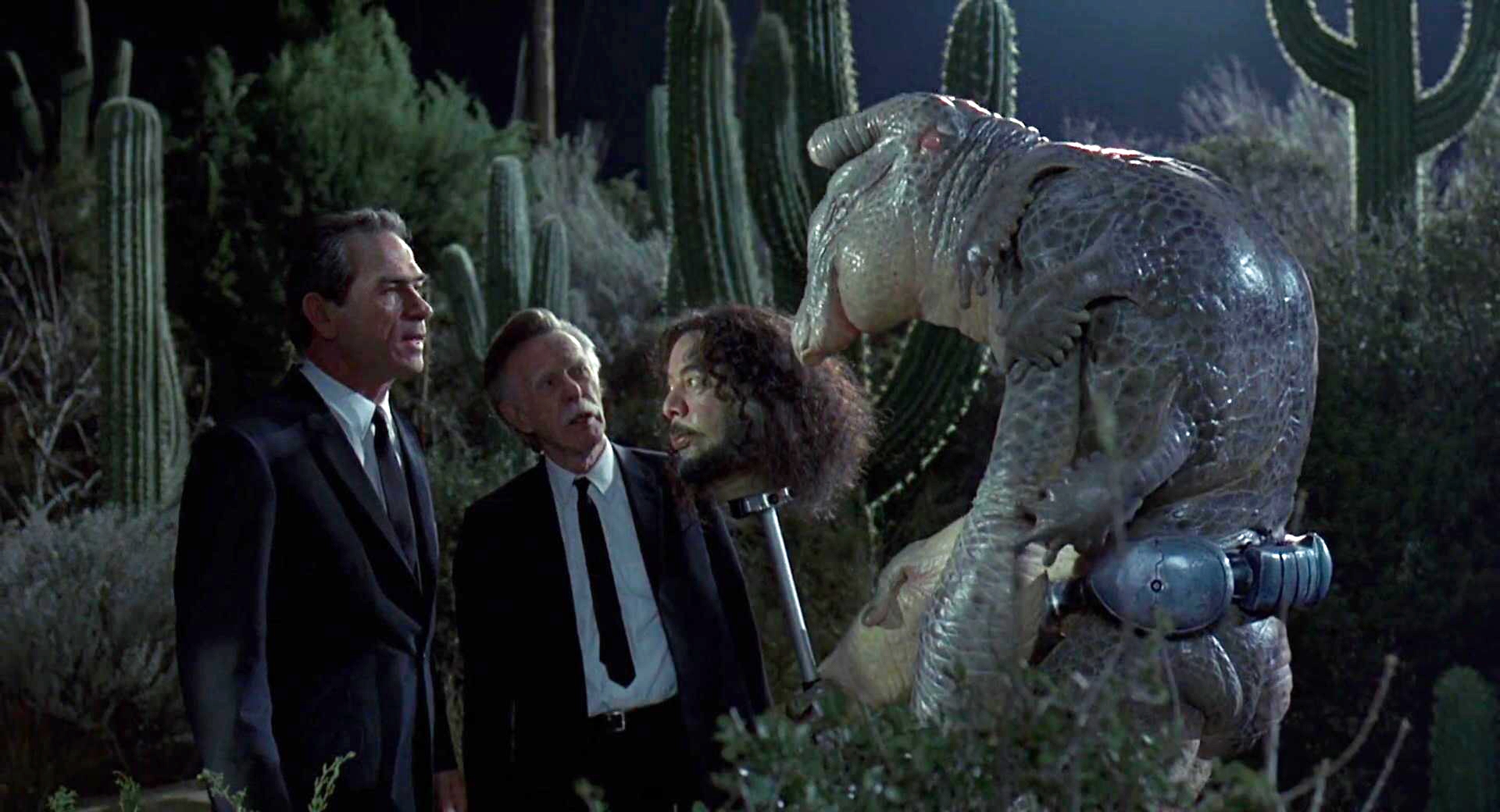

Regularly relying upon logic and extrapolations from real-life nature to design his effects, Baker sometimes found himself at creative odds with Sonnenfeld's wry take on the film's extraterrestrial-oriented comedy bits. One example is a scene involving Mikey, an extraterrestrial "illegal alien," who attempts to sneak across the U.S.-Mexico border. The humorous slant is that Mikey has simply concealed himself under a poncho, with a highly articulated fake human head protruding out of the neck hole, in his attempt to pass for a typical, if somewhat misshapen, Earthling.

In reality, Mikey was portrayed by an actor in a sophisticated animatronic costume wearing leg and arm extensions, with three interchangeable mechanical heads offering a wide range of movement. However, as Baker explains, "The character was played by a real person until the MIB agents rip the poncho off him and reveal that it's really an alien holding this head on a stick. We made a replica of the head of the actor who played Mikey as a human. It which was radio-controlled and as realistic as we could make it, but it just had a stick coming out of the bottom.

"Barry said he wanted Mikey's disguise to be crude, and I said, 'Well, then why isn't the head crude? It should look more like a ventriloquist's dummy." But Barry said, 'No, I want the head to look perfectly real, but I want just a stick coming out the bottom.' And I kept arguing the logic of this. I said, 'Instead of a stick, why don't we have a control apparatus with levers worked by this weird froglike hand so you could see how the head was controlled?' 'No, no, no, I don't want that.' 'What if there were wires coming out of the head that plugged into the belt of the alien wearing it and you could assume he controlled it that way?' 'No, no, no — I want a stick with a head on it!' I just thought it was weird."

One of Baker's most unique characters for MIB was Edgar (Vincent D'Onofrio), a 12' space bug hidden inside a human skin who undergoes a progressive deterioration throughout the course of the film. "I don't know how the alien fits inside," admits Baker, "but we went for this ill-fitting look, as if this dead human skin was stretched over a form that wasn't right. In the script, they had him adjust his neck a little bit to smooth the skin out, but I thought it would be cooler if he grabbed onto the back of his scalp and stretched his face really tight against this alien form underneath. So we went from this droopy, baggy, weird face to this really tight, stretched-out face."

Baker's concept could only work with the cooperation of a very patient actor. Thankfully, D'Onofrio allowed the makeup maestro to pull and push his skin in countless uncomfortable ways before applying the prosthetics, so he could then stretch the makeup to the max. Baker explains, "A silicon gel-filled appliance was glued to his face and ran to the top of his head, where he could actually grab it and physically distort his face into something that was quite hideous."

Baker also created two animatronic talking versions of Edgar in giant bug form, but script rewrites demanded that the creature fight the MIB rather than discourse with them. "Edgar was one of those designs we went on and on with," Baker says with a sigh. "I don't know how many drawings we did, but the design they eventually approved was a real mix-and-match hodgepodge of 47 other drawings. I thought it looked like something that would never live and didn't deserve to!

"When the Edgar bug finally came out of Vincent D'Onofrio, he had lengthy dialogue to deliver with this ridiculous bug mouth, so we built two big mechanical bugs that talked. I kept saying, 'It's going to be ridiculous when we hear a normal human voice coming out of this giant bug monster, but they said, 'No, no, he has to talk!"'

Somehow, that notion changed before any scenes involving Baker's mechanical puppets were shot. "Movies are ever-evolving things," he notes philosophically. "Unfortunately, the way they make films these days, they get a release date and then constantly rewrite the script through the course of making the movie. Meanwhile, we have start designing and building our stuff in preproduction because it takes a lot of time to do right. The night before we were going to shoot the scene with Edgar, they rewrote the scene again. At that point, Barry said to me, 'I don't think we're going to use this.' I was quite disappointed. But I'm sure it was ultimately the right decision for the film."

Baker's Edgar design ultimately became a 3-D template for animators at Industrial Light & Magic, who cyber-scanned a scaled-down maquette of the bug-like beast for their CG model. ILM also created a CG Mikey for one shot in which he "attacks" U.S. Border Patrol guards.

The last-minute addition of a sequence depicting newly arrived extraterrestrials checking in at the Men in Black headquarters also forced Baker to do something he'd never done before: subcontract. He hired Steve Johnson, Bart Mixon and KNB Effects to flesh out the scene with seven additional creatures. "I felt that there needed to be something like the Star Wars cantina scene, because the story explains that there are hundreds of these aliens on Earth," Baker remembers. "Unfortunately, the scene's a throwaway and it never became what I'd imagined. There were probably 10 aliens, but you see maybe six of 'em."

Despite the disappointments, Baker concludes, "What I really enjoyed about Men in Black is that we did at least one creature with just about every technique I've ever used."

— Ron Magid

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.