Ghostbusters II for Laughs and Liberty

Cinematographer Michael Chapman, ASC brings a new look to this NYC-set supernatural-comedy sequel.

This article was originally published in AC, Aug. 1989

At the start of Ghostbusters II, the Busters have fallen on hard times. It has been five years since they last saved humanity from the horrors of an oversized Stay Puft Marshmallow Man, and they've been forced into performing various odd jobs because a skeptical New York City justice system has labeled ghostbusting illegal.

The law of the land soon changes, however, when the Ghostbusters discover that a buildup of negative energy in New York City has created a river of psychic sewage underneath the city. As if that isn't bad enough, they also learn that the spirit of an evil tyrant from the Middle Ages, Vigo the Carpathian, has decided to make a comeback. Suddenly, the Ghostbusters are back in business, and they must use every trick they know to stop Vigo and this river of slime from turning New York City and the world into a caldron of bad vibes, bad thoughts, and bad attitudes.

“Although I grumble and complain a lot, I still enjoy the problem solving. It would be silly to say that I don’t.”

— Michael Chapman, ASC

Ghostbusters II is, of course, the follow-up adventure to the 1984 comedy smash Ghostbusters, and once again teams Bill Murray, Dan Aykroyd, Harold Ramis and Ernie Hudson as the title characters. Also returning to do battle with forces from beyond are Sigourney Weaver, Rick Moranis, Annie Potts, and director Ivan Reitman. The sequel proved to be a reunion for Reitman and the cast, but several new additions to the ghostbusting team were made, most notably, director of photography Michael Chapman, ASC.

“I've always loved the look of Michael's movies," explains executive producer Michael Gross, “but he was actually first recommended to us by Bill Murray, who had worked with him on Scrooged. Bill said great things about him and so did our production designer, Bo Welsh, who'd worked with Michael on The Lost Boys. In fact, a lot of people told us, 'You've got to work with this guy. You'll love him. He's fast.' And he is. More importantly for us, he's also very, very good."

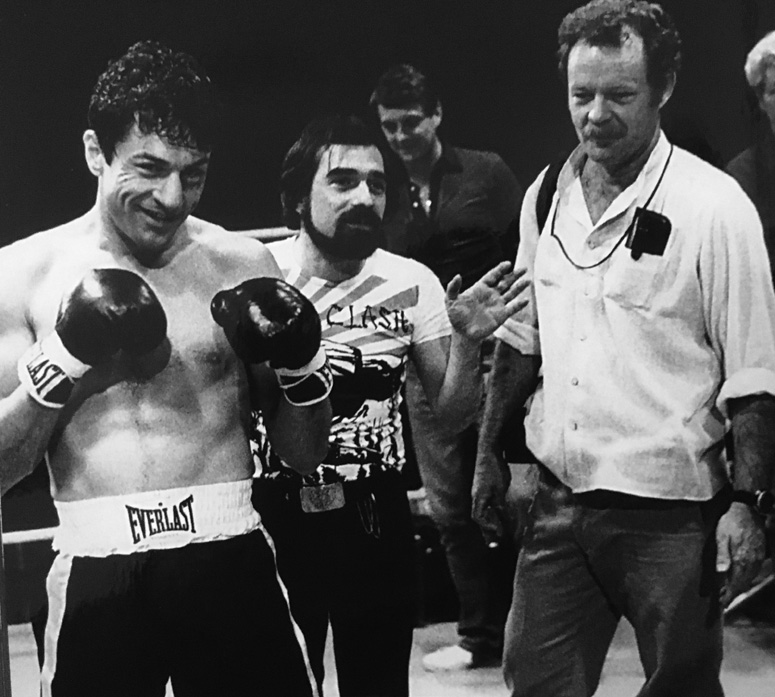

A list of movies shot by Chapman includes some of the most offbeat and interesting films made in the last 20 years. Hal Ashby's The Last Detail, Martin Scorcese's Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, Philip Kaufman's The White Dawn and The Wanderers, and Robert Towne's Personal Best are just a few of his credits. In addition, the veteran cinematographer has also directed the Tom Cruise film All the Right Moves and Clan of the Cave Bear, and, early in his career, worked as Gordon Willis, ASC’s camera operator on the classic films The Godfather and Klute.

At 53, Chapman proves to be a modest, somewhat irascible sort who constantly downplays the "magic" in moviemaking. "It's very difficult to make this stuff sound more difficult than it really is. This is an industrial process. You do this and that and the other crew members do their tasks, and if everyone does their jobs right the movie comes together. In general, what people take for inspiration and art in movies is really just technical problems solved really well."

Actually, Chapman isn't comfortable with the notion of being interviewed. But, after some prodding, this perceptive cinematographer agreed to discuss the technical problems he faced on Ghostbusters II and many of his other films.

To begin his work on the new Ghostbusters adventure, Chapman first referred to the work done by cinematographer Laszlo Kovacs, ASC, in the original. "I looked at the first Ghostbusters quite a few times before we started filming the sequel," he says, “just to get down the patterns of what happens when the boys pull the triggers on their guns, and the lighting patterns when some of the ghosts appear. Then, after that, I didn't worry about it. After all, Ivan and the guys know the first movie better than I ever could — they made it. And the sequel is very much their movie. I hope I lit it well and did a good job and helped out, but it's very much their movie. They knew exactly what they were doing."

What no one knew, however, was the response they would receive when the Ghostbusters II production began last autumn on the streets of Manhattan. "When we were in New York City," Chapman recalls, "people would scream at us: 'Ghostbusters! Ghostbusters! Who are you going to call?' The streets were lined with unpaid extras just chanting and yelling because somehow Ghostbusters tapped something. Frankly, I think even Ivan and the boys are at a loss to explain it. I don't think they had any idea the first film was going to do that. Certainly Ghostbusters is a funny movie, but why it was the phenomenon it was I have no explanation for.

"My own six-year-old son is very sophisticated about movies because he has been around movies all his life and usually could care less. Well, he was desperate to come on the set and see the Ghostbusters. Not because it was a movie, but because they were the Ghostbusters. And our eight-year-old daughter was the same. They were both mesmerized by the idea of it being Ghostbusters."

In New York, the crew shot various day and night exteriors, including scenes for the film's climactic battles between good and evil. Early in the movie, the Ghostbusters discover a new form of ectoplasm — "psycho-reactive" slime which responds to positive and negative emotions. Ultimately, the busters use this "mood" slime to enlist the aid of the Statue of Liberty. They spray the inside of the statue with the slime and bring her to life. Then they take her on a walk through downtown Manhattan to do battle with Vigo the Carpathian.

For Chapman and the crew, bringing Lady Liberty to life was one of the film's biggest challenges. To accomplish this, they first spent two weeks shooting numerous night exteriors on the streets of New York. Many of these shots were designed to serve as background plates for the special effects created later by the wizards at Industrial Light and Magic.

“Any night exterior, especially a night exterior that has a lighting pattern dictated by a city — lit buildings here and lit buildings there — is not that difficult in concept," Chapman says. “It just takes a lot of manpower, lugging cables and lights. A night exterior is essentially like a set. You've got a large black background and you can do whatever you want with it. And it's made even easier if the reality of the night exterior tells you pretty much what the source of the light has to be.

“We were shooting with 5295, which is a fairly fast tungsten film. I rate it lower than most people because I want it to have a good full negative. In Ghostbusters II there was going to be optical work all through the movie and there was no telling when they might need to do some kind of extra optical work on the film. I just wanted to have a built-in safety factor so that if they had to go an extra generation, they would always have a good negative to do it with."

The end of the movie takes place around a museum similar to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where Vigo the Carpathian is trying to return to the earth by stepping out of a portrait painted of him many centuries ago. In reality, the museum seen in the film is an old customs house located in downtown Manhattan at South Ferry. “There was the customs house and then a park in front of it, and there were big buildings that come to a triangular point at the other end of the park. We had a week of night shooting and had to light four or five blocks, so we used a lot of lights. We had two Muscos, which are big portable stadium lights, plus a lot of other things.

“But you mustn't make that sound like some kind of feat," Chapman again protests, this time with a smile. “It isn't.

You aim some lights and hit something and you get an exposure. It's not brain surgery what we do — although, given the state of brain surgery, perhaps it is."

Chapman, who worked with Carl Reiner on Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid and The Man With Two Brains, says that comedies do require a slightly different touch than other kinds of movies: "In general, it affects you in framing and lighting a little bit. You use a little more fill light, and you don't go in for some soul-wrenching close-up of somebody agonizing, because of course they're not. You stay back a little further and you watch them tell jokes."

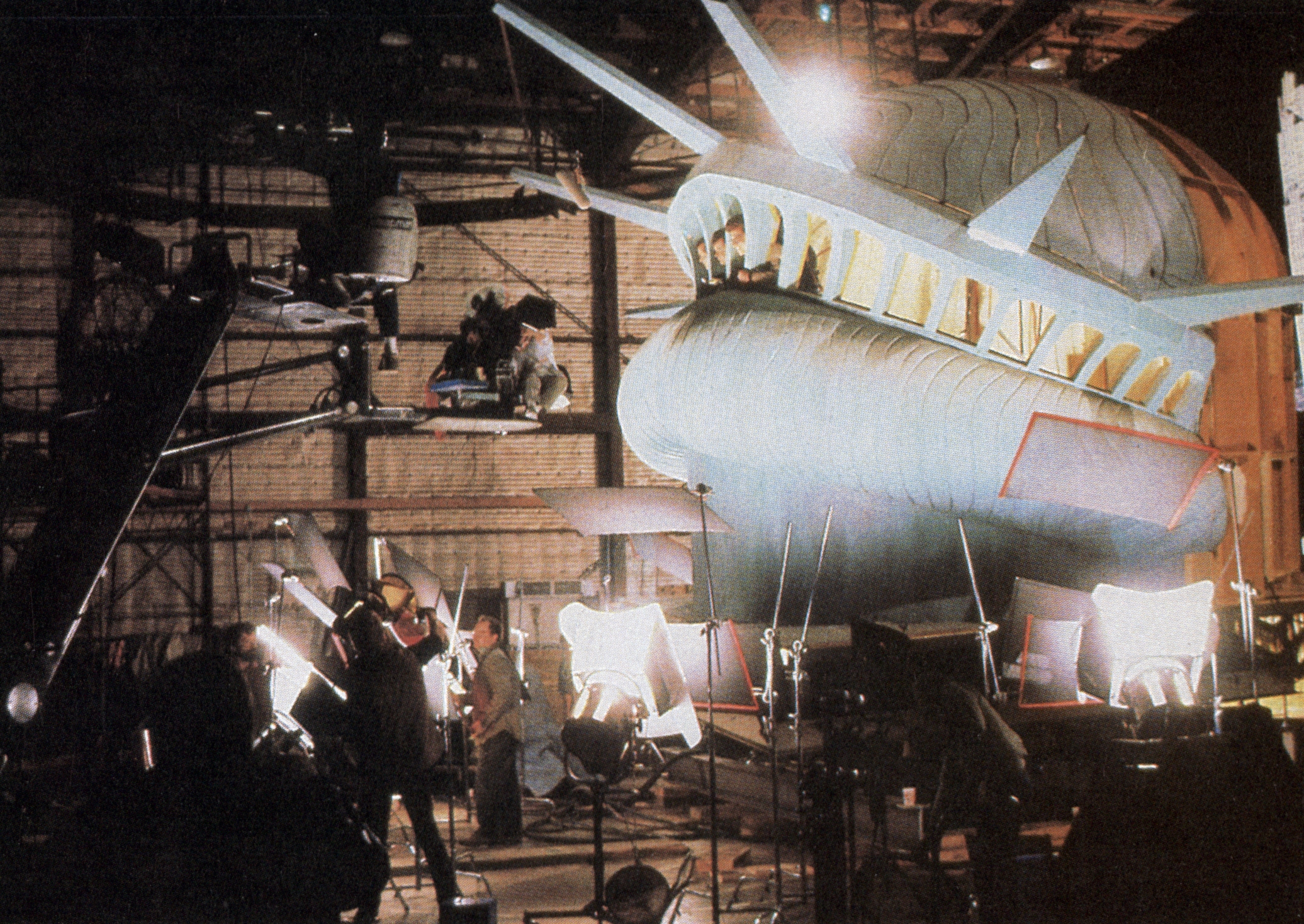

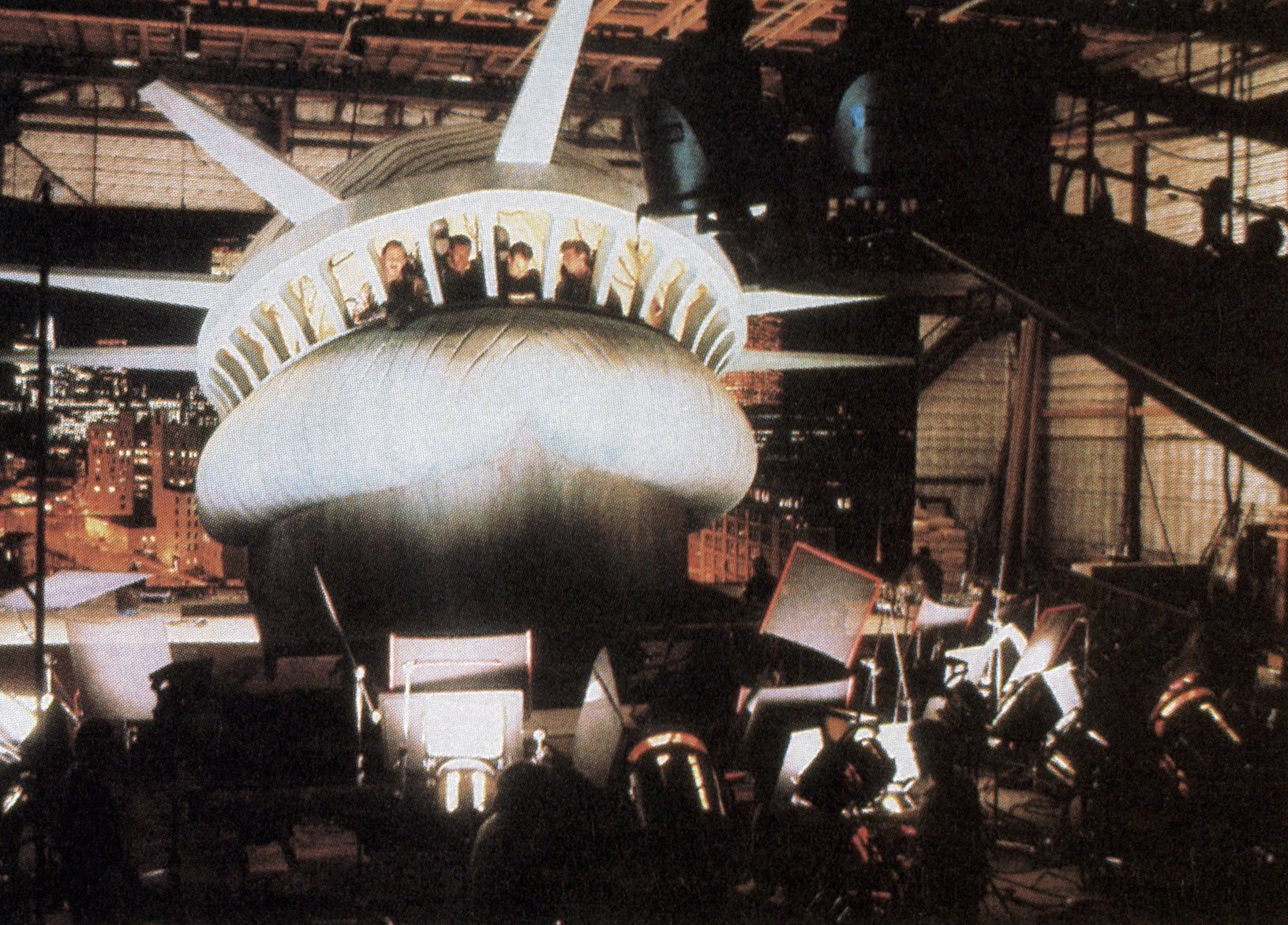

After exteriors in New York were completed, the crew returned to Los Angeles for several months of filming at The Burbank Studios. Among the many scenes shot were close-ups of the Ghostbusters inside a mockup of the head of the Statue of Liberty. In the film, these close-ups are intercut with miniatures and an actor dressed in a detailed Liberty body costume.

The large scale head itself was an exact duplicate of the real statue, except that the glass was removed from the windows, and the whole head was built approximately 30 percent bigger so the boys could be seen more clearly. The mockup was mounted on gimbals to give it a rocking motion, and placed in front of large backdrops or transparencies of nighttime New York buildings, shot from about 100 feet above street-level to match the height of the statue. These transparencies were lit from behind.

"We had fun with the head," Chapman recalls, "although we managed the effect partly by accident. We had two big transparencies hung in front and back of the head. I didn't know at exactly what height to hang these to get the eyeline and the horizon line, so I had them hung on winches that enabled them to go up and down. I also had them on tracks so they could move forward or backward so I could get just the right amount of perspective. Once we had that we thought, 'Well why not make the backing move during the shot as if they were walking away from the backing? Since we can't actually make the head move away from the background, we'll make the background move away from them.' "

"Lighting the head itself was relatively simple," he adds. "If they were walking across the water and there were lights, all the light was from below bouncing up. If they were walking the streets most of the light was again from below from people shining lights and the lights of the streets. So it really wasn't very difficult to shoot. We had a good time. We just hung the camera on a big crane in front of the head, set the backing in motion, made the gimbal rock back and forth and let the Ghostbusters just be Ghostbusters."

Another complex physical effects sequence occurs earlier in the film when the Ghostbusters find themselves on trial in front of a less than sympathetic judge. During the proceedings, an evidence jar filled with psycho-reactive slime erupts into the ghosts of two convicts the judge personally sent to the electric chair - the Scoleri Brothers. The ghosts immediately start trashing the courtroom, convincing the judge that maybe the Ghostbusters aren't lunatics after all. He quickly reinstates the Busters' operating license so they can put the Scoleri Brothers back on ice.

"The courtroom was a big set and there were lots and lots of physical effects," Chapman notes. "It was also a little hairy because it was the first thing we did when we came back from New York so we hadn't fallen into a rhythm and gotten everything going. And those were the first big physical effects that we had. In the end, we used lots of lights, including several old time lightning boxes that make an arc. More than anything, scenes like this require a lot of labor. It's just plain lifting stuff up and getting it in the right place and being clever about how to lift it. And it's thinking ahead to make sure that you don't at the last minute realize, 'Oh, my God, I must have a lightning box up above because the ghost is shooting down."

Ghostbusters II is broad comedy, but not everything Chapman had to contend with was on a grand scale. In the five years since the first adventure, for instance, Dana (Sigourney Weaver) has had a baby boy named Oscar, portrayed in the film by identical twins William and Henry Deutschendorf.

“The babies were extraordinary," Chapman says. “They smiled and laughed, hit their marks and did everything on cue. We even floated one with little wires. He was perfectly safe, of course, but we thought he might not like it. Well, he loved it. We just floated him across the restoration studio and he had a big smile on his face and thought it was wonderful. God, those kids saved us weeks. They were amazing — almost supernaturally good."

Perhaps the greatest challenge in bringing Ghostbusters II to the screen was the production schedule itself. Columbia green-lighted the project late last summer with the stipulation that it had to be completed for release this summer. This gave the filmmakers less than nine months to complete a production filled with special effects and action.

“A lot of the energy and speed and élan of a movie comes up through the crew to the people above the line, much more than people understand," he says. “We were very, very lucky on Ghostbusters II. Our schedule was tight because of the post-production schedule and the release date, and nobody thought it was possible. The company was prepared to work Saturdays and Sundays and 27 hours a day, but in the end we didn't have to. Not just because of my crew or because of me or anything like that, but because the whole ensemble worked well together. And Michael Genne, Gene Kearney, Les Kovacs and all those guys bear a lot of the responsibility and should get the glory because they all worked very hard."

One of the last scenes filmed at the Burbank Studios was a shot of the front of the museum being sealed off by a wall of slime just before the final battle between Vigo and the Ghostbusters. In reality, physical effects supervisor Chuck Gaspar rigged a mock-up of the front of the museum with slime jets that oozed slime on cue and covered the mock-up. As usual with complex special effects of this kind, not everything went as planned, and one of the jets actually blasted one of Chapman's five cameras set up to record the event. But Chapman wasn't worried.

"Yes, one of the cameras got covered with slime but cameras are pretty rugged these days," he says. "You can wash them off and they're all right. It's not a good thing I think to be sentimental and worry about cameras. They're just pieces of metal and you can do whatever is necessary to them. The only thing about breaking them is that it costs a lot of money and Panavision gets mad, but other than that they're just pieces of metal with glass in them. They're not anything sacred and you mustn't take them too seriously."

Chapman has been putting cameras at risk for more than 25 years. He grew up in New England, mostly around Boston he says, and then attended Columbia University in New York City. "They didn't have any film school in those days. I studied American history and literature. In those days you didn't actually have to major in anything so I sort of took whatever interested me.

"Like many people in the days before film schools I just fell into movies by accident. Movies are the last refuge of scoundrels. I just happened into being an assistant loading magazines into cameras. I had a wife and child, and then two children, and I had to make a living. So I started out as one did in New York, almost entirely doing commercials and documentaries and things like that."

In the early 1960s Chapman worked at a commercial house where Gordon Willis was also working, and the two became fast friends. Then, when Willis set out as a director of photography, Chapman served as his camera operator.

"I was operator on his first dozen or so movies. We did everything together for about six years. The Godfather is the most famous, and I guess the best, of what we did. Klute also had some fame. We did whatever came along. He was the hot man in New York at that time. If you were going to go to New York and you had some pretense of style, you tried to get Gordy. People wanted Gordy, and I came along as part of the package."

Chapman and Willis worked together for six years before separating on The Godfather, Part II. Unlike the original Godfather, the sequel was a Hollywood film, and while Willis had his union card in Hollywood, Chapman did not. So he stayed on in New York City and soon after got his own assignment as a director of photography on Hal Ashby's The Last Detail.

"I had operated Hal Ashby's first movie — The Landlord — with Gordy, so I knew Hal," Chapman explains. "When he came east to do The Last Detail, Haskell Wexler was originally going to do it and I was going to operate. I don't remember the details, but for various union reasons, Haskell couldn't shoot it in the east or in Canada, so Hal turned to me and said, 'Well, why don't you do it?' So I did. I owe a lot to Hal because he gave me my first job as a DP.

"Of course, I was terrified," he adds. "I think everybody is on their first feature. You just think you're a total fraud and that you're going to be found out any second. You're so amazed when you get through the day, and when you see the rushes and there's an image there. You just barely get through one day. After weeks and weeks you begin to think, 'Well, maybe they won't fire me and I will get through this.' But this was rather a big deal for me because it had Jack Nicholson and was a Bob Towne script."

Chapman's fears were unsubstantiated, and he next went on to serve as director of photography on Philip Kaufman's The White Dawn, a circa 1896 Arctic adventure about three stranded whalers who are rescued by Eskimos.

"We shot The White Dawn in the real Arctic on Baffin Island north of Canada. We were based in a place called Frobisher Bay where there had been a very small American Air Force unit. God knows what they were doing there — they were going to protect us from the Eskimos or something. But they had left and abandoned some barracks, which we dug out of the snow, refurbished and lived in. We were out there months and we also camped out and lived out on the ice.

"We had cameras freeze less than you think. We took a lot of care and did all the things you had to do, and we were very lucky. This was before Panaflex. Panaflexes would have frozen, I know, but we had an old studio Panavision camera, PSR I believe it was called, and it was marvelous for some reason. It just never did break down. We had pan-Arris and they broke down a lot, but the basic camera never did. The dogs ran away with it on a sled, it got dropped on the ice — amazing things happened to it — but somehow it never broke down. It was a wonderful camera. Every month or so a guy from the Panavision office in Toronto would struggle up to the Arctic somehow and maintain it. We were lucky. That film was hideously difficult, but also exciting."

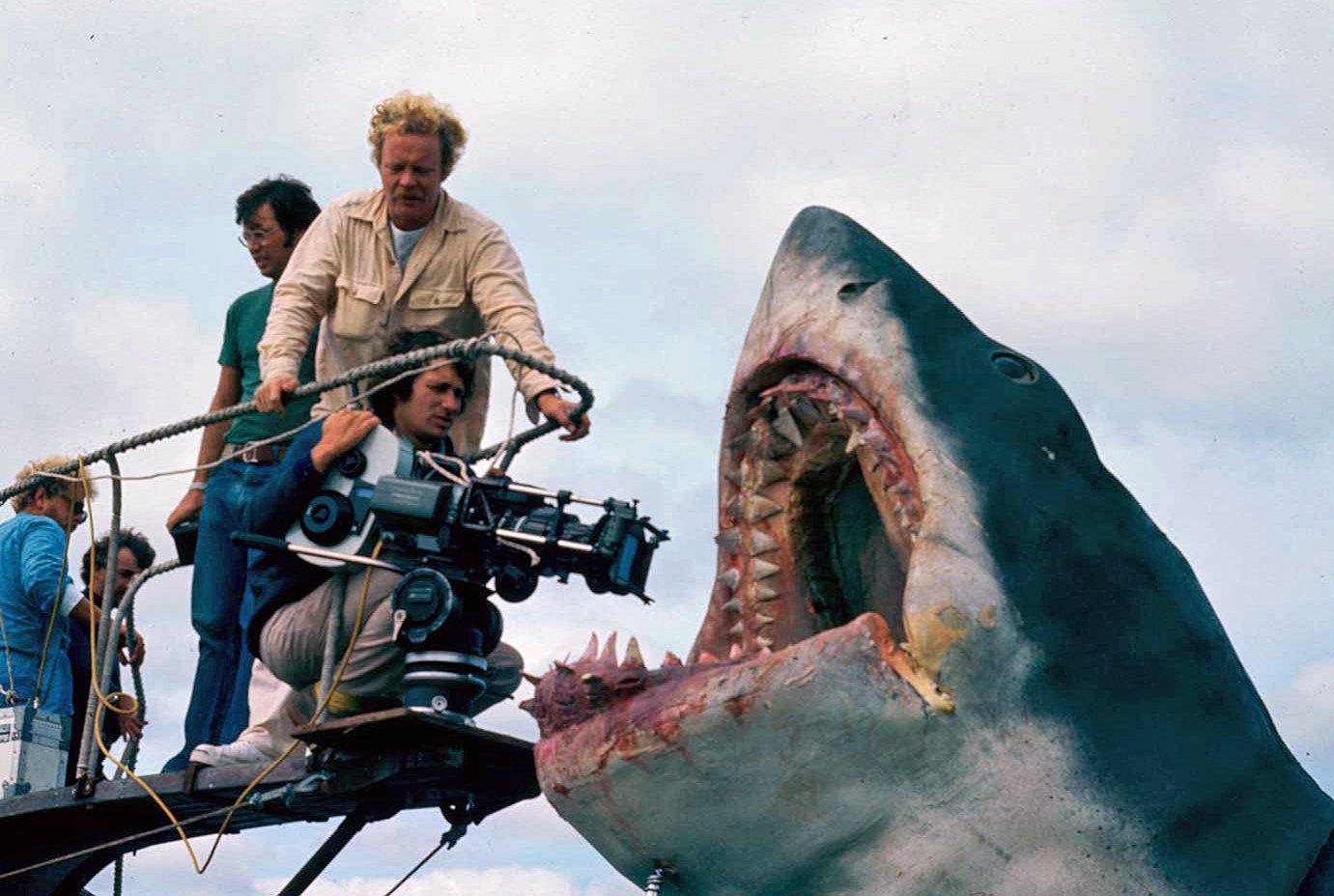

Returning to New York to thaw out, Chapman found the film scene relatively quiet, so he took a camera operator position on another unusual project — the original Jaws.

"Jaws was marvelous fun," he says. "The shark always broke down so we were being paid to be on the garden spot of the East Coast and lie in the sun and dive for clams and things like that while they fixed the shark. Once the weather got warm, Jaws was really a lot of fun. And frankly I'm rather proud actually that it's really well operated. Once they go out into the ocean, it's pretty much a hand-held movie, and that's difficult to do."

"What was good about Michael was that most of Jaws, especially the work out at sea is hand-held," says Steven Spielberg. "I don't think anybody has ever realized that. This was before the Panaflex or the Steadicam, and I don't think anyone has ever fully appreciated what talent and strength it takes to handhold a movie on a pitching boat in six foot swells and keep the horizon completely horizontal across the frame by presuming you're a gyroscope. That's exactly what Michael Chapman did on Jaws, and I think he made a great contribution in so doing."

After the highly successful Jaws, Chapman was able to shift back into the role of director of photography on Martin Scorcese's Taxi Driver.

"Taxi Driver was one of those lucky accidents. A lot of people who became extremely expensive later on were, for various reasons, all together at one time and rather cheap. It was a real low budget movie. It was made for only two or three million dollars. It was just one of those things that happened where everybody's interests and energy and age — we were all a lot younger — came together at the right time. We were all people who knew something about New York and had genuine emotions about New York both pro and con. And it was one of those things that worked out. After a while we knew we were onto something. The dailies were pretty spooky stuff, they really were."

Chapman went on to work with Scorsese on The Last Waltz and Raging Bull. "Raging Bull was long and intense," he says. "It's a wonderful movie, but, I guess, for myself, I prefer Taxi Driver. Not the photography, because the photography is quite primitive, but as a movie it seems to me Taxi Driver will last forever."

In 1983, Chapman decided to try his hand at directing with the Tom Cruise film, All the Right Moves. "I was quite pleased with it" he says in retrospect. "I didn't think it was Shakespeare, but I thought it had a certain uniqueness to it because of the location (Johnstown, PA) and the way it looked, and some of the acting I was really very pleased with. I also thought Jan De Bont [ASC] did a marvelous job of shooting it. Again, it's just a little high school football movie, but we did a few different things, such as lose the big game, and it was lost in the middle of the movie.

"Everybody should direct one movie, because no matter what the subject, you're so excited that you're going to direct a movie that you do actually get emotionally involved with it. I was lucky enough in All the Right Moves to be emotionally involved in the story. It was kind of a valentine to my two older sons because I had been divorced when they were kids. The film is partly about fathers and sons, and that meant something to me."

Clan of the Cave Bear was Chapman's follow-up project, a film he prefers not to talk about. His disappointment with Clan forced him to rethink his desire to stay a director.

"After Clan of the Cave Bear, my services as a director were not that much in demand," Chapman admits in a matter-of-fact tone. "And I found that short of a movie about something that I really passionately believe in, then directing seemed like a job like any other. The director is involved with every aspect of the process, which is fine. I don't mind that. It's just that a lot of other people are involved in almost every aspect of the process. But when you're the cameraman nobody's really involved with it but you, the director and the lab.

"The way movies are made in the United States today, one of the most free things you can do is be a big-time director of photography," he adds. "If you have a track record and a certain history behind you so people aren't going to say you're an idiot, you have far more autonomy than all but the very biggest directors. You see, all the people working on a movie set think they know how to direct, think they know to write, and think they know how to edit. But they know they don't know how to shoot. They know they don't know how to go out there and figure it all out. So if you have brought in projects that look pretty good and you're known for not making many mistakes, you have a kind of autonomy that even a director doesn't have."

With Ghostbusters II now in theaters, Chapman is following it up by working as cinematographer on a new comedy [Quick Change] being co-directed by Bill Murray and Howard Franklin in New York. For the time being, Chapman says he will continue working as a director of photography unless he finds a project that he really wants to direct.

"Movies have been very good to me and I have no complaints," he notes in retrospect. "I have been working as a DP for a very long time so some of the blush is probably off the rose, but I do still have fun. I enjoy the process in a certain grumpy kind of way. I enjoy making movies, making them fast, and doing them well. And, although I grumble and complain a lot, I still enjoy the problem solving. It would be silly to say that I don't. And I enjoy those occasional moments when something slightly beyond problem solving seems to occur, almost by accident. Those moments are perhaps not too frequent but they do happen, and when they do you realize why film is the great art form of the 20th century, and why you are privileged to be a part of it, however small."

Chapman was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2004.

Access every issue of AC and every story from more than 100 years of coverage with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.