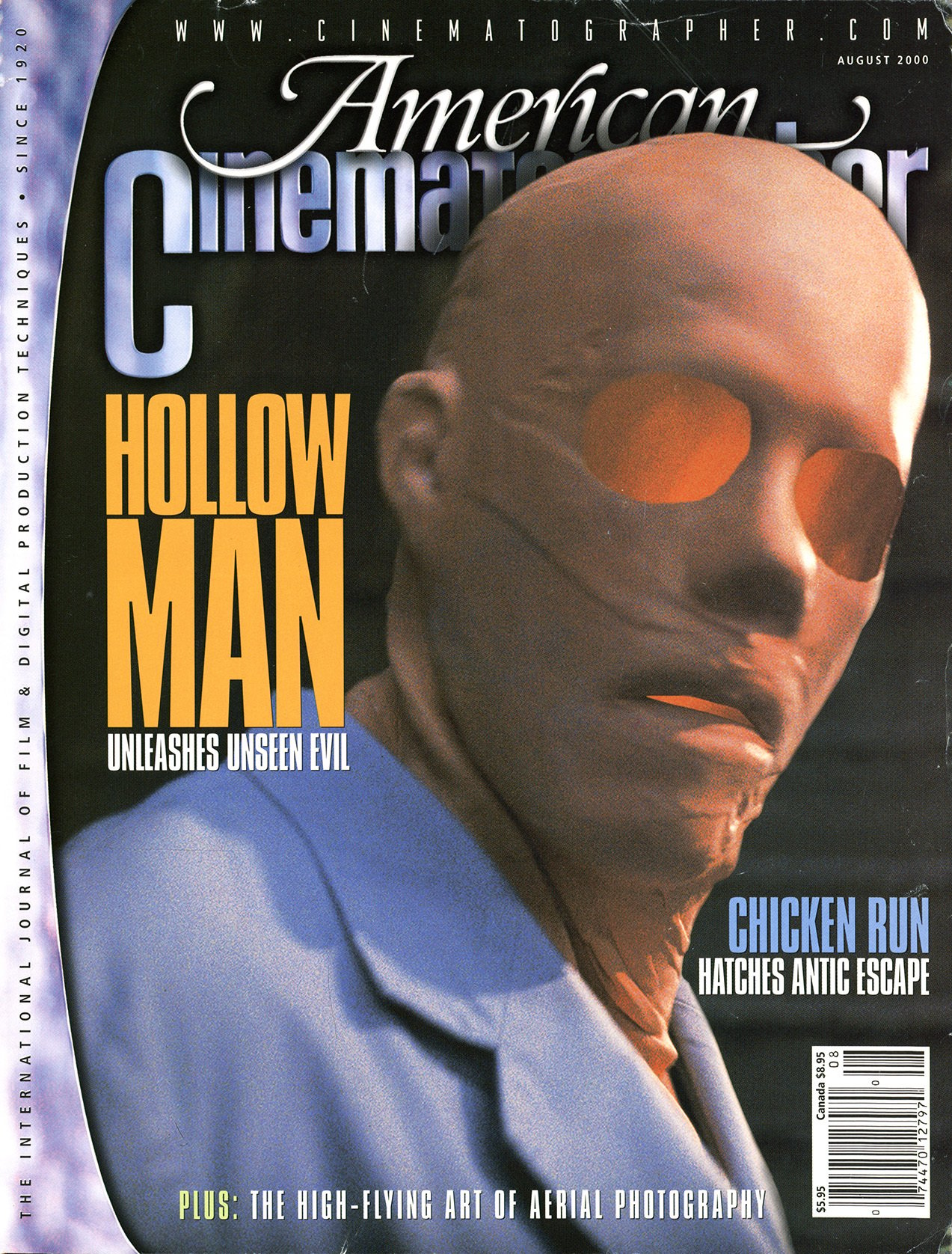

Invisible Force: Paul Verhoeven Q&A

The director imbues Hollow Man with his usual flair and full-blooded gusto.

Unit photography by Stephen Vaughan, SMPSP

Director Paul Verhoeven says his interest in film began when he was a child in Amsterdam during World War II, after the British bombed a film lab near his home and the explosion scattered rolls of film throughout the neighborhood. “I picked them up and became fascinated with the pieces,” he recalls. His father, an elementary school principal, showed documentaries about cattle and farming to his pupils at a time when the occupying Nazi forces prohibited all other moviegoing. “Then, in 1946, American movies started to come into Holland again, and I got to see films like Gone with the Wind — what a difference that was from How to Feed Your Cattle” Verhoeven says with a hearty laugh. He went to the movies three times a week for the next 10-15 years, becoming a self-proclaimed B-movie connoisseur.

Verhoeven began making short films at the University of Leiden while earning a degree in mathematics and physics, and after he was drafted into military service he made several documentaries for the Dutch Navy. “I thought, ‘Mathematics is fine, but filmmaking is better,’ and I decided to become a filmmaker,” he says. After making several acclaimed films in Europe (including Turkish Delight, Keetje Tippel, Soldier of Orange, Spetters and The Fourth Man), Verhoeven moved to the United States.

Few of the films he has made since have been released without controversy. RoboCop, Total Recall, Basic Instinct, Showgirls and Starship Troopers all demonstrated that Verhoeven is not afraid to depict violence and sex in ways that make the MPAA extremely nervous. (Showgirls was among the very few films released with the NC-17 rating.) AC recently asked him to discuss how he brought his famously graphic style to bear on his latest picture, the sci-fi thriller Hollow Man.

American Cinematographer. How would you describe the tone of Hollow Man?

Paul Verhoeven: Dark, scary, intense. The whole story is really [inspired by] Plato’s Republic; in the second book, Plato tells the story of a man who finds a ring that can make him invisible, and describes what such a man might do with this power. The man goes to the court, sleeps with the queen, kills the king and becomes king himself. Plato says man is not just and decent because of internal morals; [rather,] he is obedient to the restraints of society. If you remove those restraints — if a man were to become invisible — he would steal whatever he could get, enter every house, rape every woman, kill all the men and basically behave like a god. That is what Plato foresaw about invisibility. I’m not sure he was right, but it is a very interesting possibility to explore.

How would you describe your approach to the film?

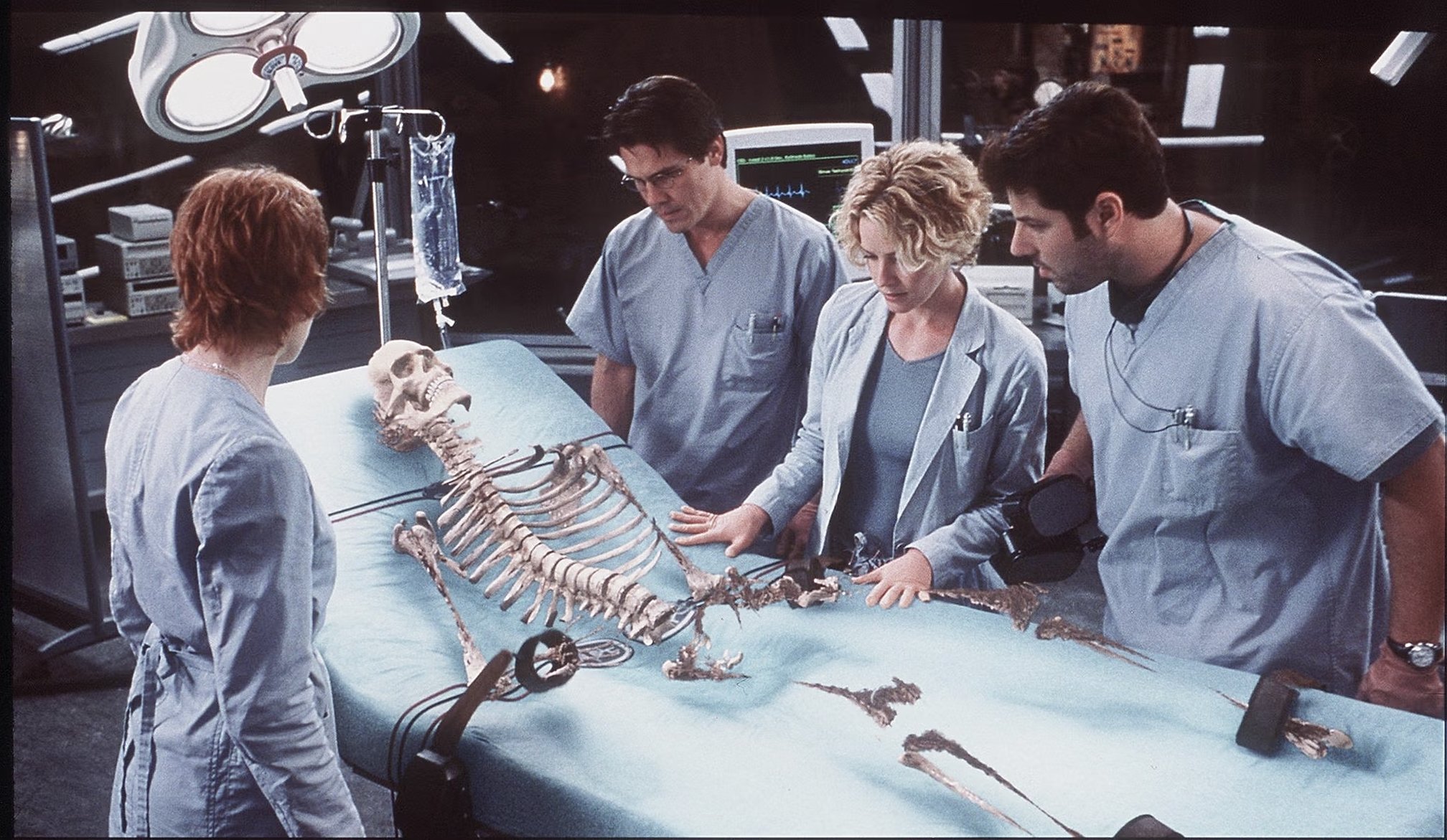

When I first read the script, I thought it was going to be easy [to shoot]. I thought that Sebastian Caine [the scientist portrayed by Kevin Bacon] would be merely a digital addition to the scenes, and that Kevin would only be there for about 30 percent of the shooting. I thought that all I had to do was shoot my plates with the other actors, then give the footage to the digital people so they could go off and add in whatever hint of Sebastian was necessary. However, when I started to talk to visual effects supervisor Scott Anderson at Sony ImageWorks, I started to realize that to do this film well, we would need Kevin on the set the whole time, whether his character was supposed to be visible or not. Of course, he is rarely completely invisible. If you could never see him at all, and you just heard this disembodied voice, that would get really boring. So we came up with pretty much every conceivable way that you might be able to see an invisible man, and I have to credit [screenwriter] Andrew Marlow for very ingeniously working those situations into the story.

[For example], if Sebastian is walking in the rain, then the raindrops are bouncing off his body; although light rays can pass through him, particles cannot, so the water rolls down his body and we see Kevin’s outline traced out in a waterfall. In order to achieve that technologically, we had to shoot each sequence twice with motion-control cameras. Kevin was always dressed in a blue or green leotard with blue or green makeup on his face, hands and teeth — he even wore blue or green contacts in his eyes. We would shoot one pass of the take with Kevin doing his thing, and then shoot the plate pass so that they could meld the two in the computer and see through Kevin; the raindrops would be a pantomime outline of Kevin performing. To create a human performance from a computer is still nearly impossible. Although we used a 3D computer model to enhance these scenes, the model was based on intricate scans of Kevin — his eyebrows and fingernails, even — and pasted on his real performance from the set. If we hadn’t had Kevin on the set — if we had nobody or a stand-in or a cardboard cutout — it would have been extremely abstract for the other actors to perform with Sebastian. It would be just like the old movies, a bit stiff and silly. Plus, when there are physical interactions between characters, it looks real because we really did it! When Sebastian is grabbing someone’s clothes or pushing them around, they react realistically because Kevin was really doing it!

Your visual style, which is very fluid and makes substantial use of Steadicam and dolly work, must have made working with motion control a bit taxing.

Yes, I found it extremely annoying — it is so time-consuming. It’s nightmarish, really! You shoot six, seven or eight takes of a scene, and maybe you like four of them. Then, for each of those four takes, you have to shoot a separate take for the motion-control. If for some reason that doesn’t work — for example, if the wheels on the dolly slip a bit or get stuck—you either do a lot of work in post to correct it or you have to do it all over again. It takes so much time! With a Steadicam, if you want to make a slight adjustment in framing — if the cameraman steps back and moves slightly around an actor for a better frame, for example — that same motion is diabolically difficult, even impossible, because you can’t make sharp angles on the track. They have to be curves.

The trade-off there would be spending less time on set but considerably more time in postproduction, which is often when the schedule is the tightest

Yeah, it’s a trade-off, but I’m not sure if spending more time on set was the better decision. The set is so expensive — you have 300 people standing around, and if the dolly slips and we have to go again, it kills the momentum of the shooting.

How did that affect your directorial style?

Well, when I did Starship Troopers I was more respectful of the problems that the digital artists would have in post, so I shot that film much more statically, unfortunately. There are dolly and Steadicam shots in Starship Troopers, but not that many. I didn’t want to do the same thing on Hollow Man. [Cinematographer] Jost [Vacano] was wonderful in that respect, as he is always wonderful! Jost and I have been working together for 25 years, all the way back to Soldier of Orange in 1975, and I have always tried to stage scenes for a moving camera. Back then, Jost had his own gyroscopic, Steadicam-like camera system that he invented, and we got wonderful, very smooth handheld shots. We used that all the way up to Total Recall. Jost is really keen in designing shots that have a free-floating style, which I like. For this film, he carefully constructed and planned shots, within the limitations of the motion-control, that would feel as if we were using Steadicam. Combining straight and curved track and pans, he kept a very free camera style with very complicated, regulated moves.

You’ve worked exclusively with Vacano or Jan de Bont, ASC on the 23 films you’ve directed. You’ve even spoken about choosing between the two of them much the same way a director might choose between two actors. Can you elaborate on that?

Well, I cannot use Jan anymore [because he’s a director]! [Laughs.] So that way of thinking is lost, unless I find another Jan — which I should, because I think it is good to work with a couple of cinematographers. You don’t need a new one for every movie. It’s vitally important to have a relationship and an understanding with your cameraman, and that is only built up through years of working together. In basic terms, Jost uses more blue and Jan uses more red. Jost’s work has a more matter-of-fact quality, a sense of realism. Jan’s [manner] is a little bit more [stylized] — it’s a little more elegant, a bit warmer and more romantic. With the two of them, I could go either way on a particular movie. Sometimes I chose one not so much because I thought he was better suited for a project than the other, but because the other was unavailable. I made several films with Jost that I could have made with Jan, and vice-versa. I think it would be very interesting to see the differences.

Are there any films you can cite as an inspiration to your approach to Hollow Man?

Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man! [Laughs.] Actually, I was very scared by Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein I was seven or eight, and I thought it was extremely scary.

One of the common pitfalls in a film about invisibility is the camp factor. Did that worry you?

I tried to avoid that silliness at all costs. I tried to avoid things like showing a pencil floating in the air and then being set down. I wasn’t able to avoid it completely, of course, but in general we tried to be a lot smarter in how we depicted Sebastian’s condition. The movie is supposed to be tense and scary, and those types of effects would have destroyed that feeling completely.

You’ve talked in the past about the influence Alfred Hitchcock has had on your work. Are there any sequences in Hollow Man that reflect that influence?

Yes, quite specifically! [Laughs.] Hitchcock has been a gigantic influence on my editing, camera moves, point-of-view and camera placement. I’ve studied his films continuously. In Hollow Man, Sebastian’s apartment building is shaped like a U, with a courtyard between two wings of apartments. When Sebastian is in his apartment, he can look directly into the windows of the apartments across the courtyard. He sees a girl in one apartment across the courtyard who is very beautiful, and once he is invisible, he basically goes in and attacks her. To get the proper relationship between the apartments and the proper distance and size in the frame, I turned to Rear Window. It’s a very delicate thing, because you need the windows to be a certain distance away so that with a shot of Sebastian in the foreground, you can still see detail inside the woman’s apartment with a normal lens. However, you don’t want the windows to be too close together or it seems silly and forced. We needed a realistic distance across the courtyard. [Production designer] Allen Cameron and I studied Rear Window and basically measured the distance between the apartments that Hitchcock used. We said, ‘Okay, which lens do you think he used?’ We eventually figured out how far apart the apartments needed to be and how big the windows needed to be to tell the story and make it feel real. We stole all of those answers directly from Rear Window.

Who else has influenced your work?

In the United States, I’d have to say Steven Spielberg and James Cameron. From a more personal point of view, I’d say Paul Morrissey and his movies like Flesh and Trash — movies I would call very open-minded. Those influenced me a lot, though not so much from a technical point of view. When I made RoboCop, I studied Terminator frame by frame. [I like] Cameron’s editing style and the way he depicts action, and he’s always at the forefront in terms of visual effects. He is always trying to innovate and proceed in different directions. Spielberg, aside from his amazing movies, was a direct influence on my moving to the United States. In 1978 or 1979, when I was still living in Holland, Soldier of Orange was released for the first time in the United States, and Spielberg saw it. He called me and said, ‘What are you doing there? You should come over here, and I’ll introduce you to the studios.’ And he did! He introduced me to Frank Price at Sony [which was then MGM], and we went out to dinner. I’m not too sure the movies I made later were so much Spielberg’s cup of tea, but we all go our own way.

You’ve talked a lot about the role violence plays in your films, as well as the effects of growing up during World War II and witnessing violence.

Saying, ‘Oh, it has to do with my youth’ makes it kind of understandable, but I really don’t know if it’s the truth. That was just a way to answer the question for journalists! [Laughs.] I use violence because I like violence. I’m not somebody who backs away from violence. I like to see war movies and documentaries about war; I like to see things destroyed, I like to see the flames, I like to see shooting, and I like to do that in movies. I like to see gruesome scenes. I like to see what happens when you do something violent to someone else. I prefer to show things instead of depicting them elliptically or suggesting them — that might be a more artistic way to handle violence, and it’s what people prefer nowadays, isn’t it? Suggest gruesomeness, but don’t show it. The MPAA likes that, too! My tendency is to be ultrarealistic with these things — not necessarily with the movie itself, but with [the elements of] violence and sex. I like to see what happens to someone’s organs, flesh and bones when something violent happens. Is that because of my memories from when I was a child? I don’t know. Perhaps it comes from there, or perhaps I was born genetically violent! I’m not violent myself — though verbally I can be very violent. I’m not somebody who would ever fight or hit somebody. I would try to hit them with words.

With all of the fingers that politicians have been shaking at Hollywood in the wake of some recent, horrific tragedies, especially those involving children, do you think there will be a change in how Hollywood treats violence, or in how you handle it in your films?

When there is a problem with the economy or another cultural problem or a Presidential election, Washington always takes a charge at Hollywood. We’re in the most violent century ever — which is saying a lot — but it’s silly [to say that] people become violent through seeing violence in movies. A couple of years ago, in the aftermath of [the controversy surrounding the violence in] Total Recall, I started to study this issue. I read a lot of psychological papers and studies, and the results were completely ambiguous. There is a definite correlation between violence in films and violent people, in that violent films tend to attract violent people. But there is gigantic confusion in this country about the difference between correlation and causation! There is no evidence that violence in films causes people to become violent. The same violent American movies go to Western Europe, and viewers there don’t seem to have any violent reactions! They’re watching the same movies! The only difference between the United States and Western Europe is that in Western Europe, you cannot get a gun. That’s the only real, hard fact that you can put down on the table, because they see exactly the same movies.