Vintage Indy in the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull

Cinematographer Janusz Kaminski updates a classic franchise: “It was a tremendous honor to follow in Douglas Slocombe’s footsteps.”

Unit photography by David James, SMPSP

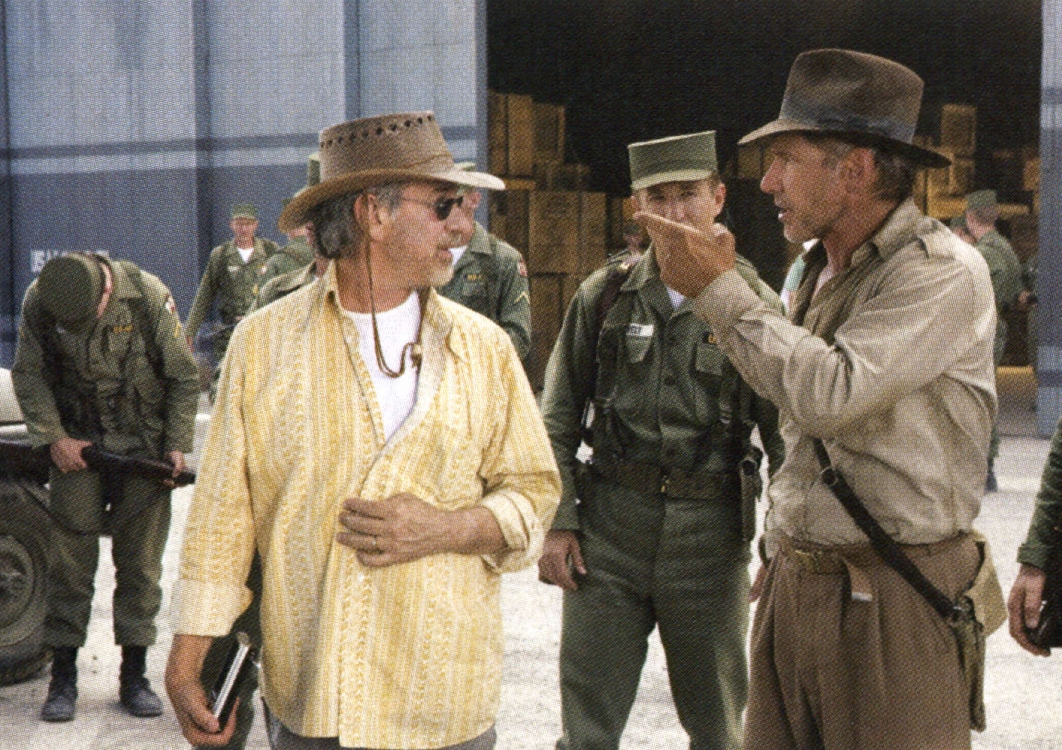

The last time we saw dashing archaeologist Indiana Jones (Harrison Ford), he was riding off into the sunset at the end of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (AC June ’89), the final film in a trilogy that director Steven Spielberg and executive producer George Lucas had begun with Raiders of the Lost Ark (AC, Nov. '81). Now, nearly 20 years later, Indy is back with a new adventure, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.

Reflecting the passage of time since the last picture was made, Crystal Skull is set in 1957, and the visual elements include ’50s Americana and sci-fi trappings. In the film, an aging Indy finds himself partnered with old flame Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen) and a young man who is possibly their illegitimate son, Mutt Williams (Shia LaBeouf). It is the peak of the Cold War, and Russian spies, led by pitiless agent Irina Spalko (Cate Blanchett), are the villains at hand.

According to Crystal Skull director of photography Janusz Kaminski, whose collaborations with Spielberg include Schindler’s List (AC Jan. ’94), Saving Private Ryan (AC Aug. ’98), War of the Worlds (AC July ’05), and Munich (AC Feb. ’06), the new picture “was a very big undertaking, much more so than the other movies Steven and I have done together. When I read the script, I was concerned with the amount of action; a lot of dialogue is delivered while the characters are fighting, kicking, riding motorcycles and jumping from car to car, so I knew we’d be covering scenes for dialogue while actors were constantly on the move. There were very complex shots, and we were also shooting anamorphic, which complicated everything even more.”

Kaminski also wanted to honor the work of cinematographer Douglas Slocombe, BSC, who shot the first three pictures. “There’s a legacy and a strong following with these movies that you have to respect, and Steven and I began our prep by watching the first three movies together,” says Kaminski. “An Indiana Jones film has to have that glossy, warm look with strong, high-key lighting. It’s suspenseful but not too dark — you always see things clearly. We also had to recognize that we couldn’t use some of the same tricks that worked 20 years ago because the audience has become more sophisticated; today, you can’t use a torch in a cave scene and have light coming from other directions. We were always asking, ‘How can we do this as well as Douglas Slocombe but make it a bit more contemporary?’

“Ultimately, I decided to forget about reality and shoot an action-adventure movie,” he adds. “I worked to create light that supports the story but doesn’t necessarily feel realistic.”

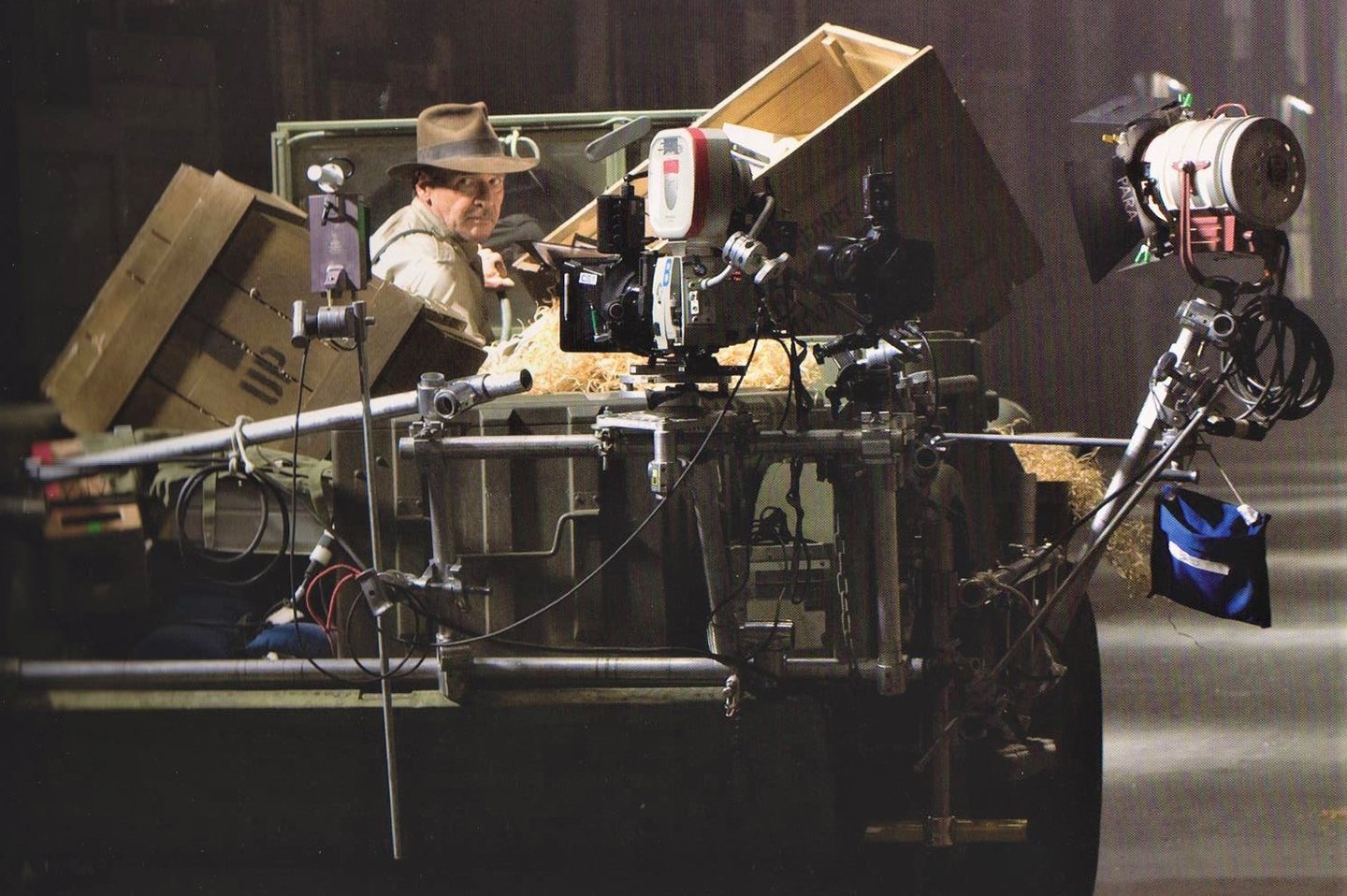

The production carried two Panaflex Millennium XLs, an Arri 435, an Arri 235, Panavision C- and E-series anamorphic prime lenses and a Primo 11:1 48-550mm anamorphic zoom. Shooting Kodak Vision2 250D 5205 and 500T 5218, Kaminski frequently softened the image with Schneider Classic Soft filters to create “an idyllic Americana look.”

Kaminski brought many of his longtime crewmembers aboard Crystal Skull, including gaffer David Devlin, camera operator Mitch Dubin, key grip Jim Kwiatkowski and 1st AC Mark Spath. Crystal Skull was primarily designed as a single-camera shoot. “Normally, we do a lot of handheld work with Steven, but he didn’t want any on this movie,” says Dubin. “However, he wanted the camera to move more dynamically than it did in the previous Indiana Jones movies, so we spent about 80 percent of the shoot on a Technocrane with a Libra head.” To film the sequence that introduces the Russian villains, the team used the Ultimate Arm, a car-mounted robotic crane.

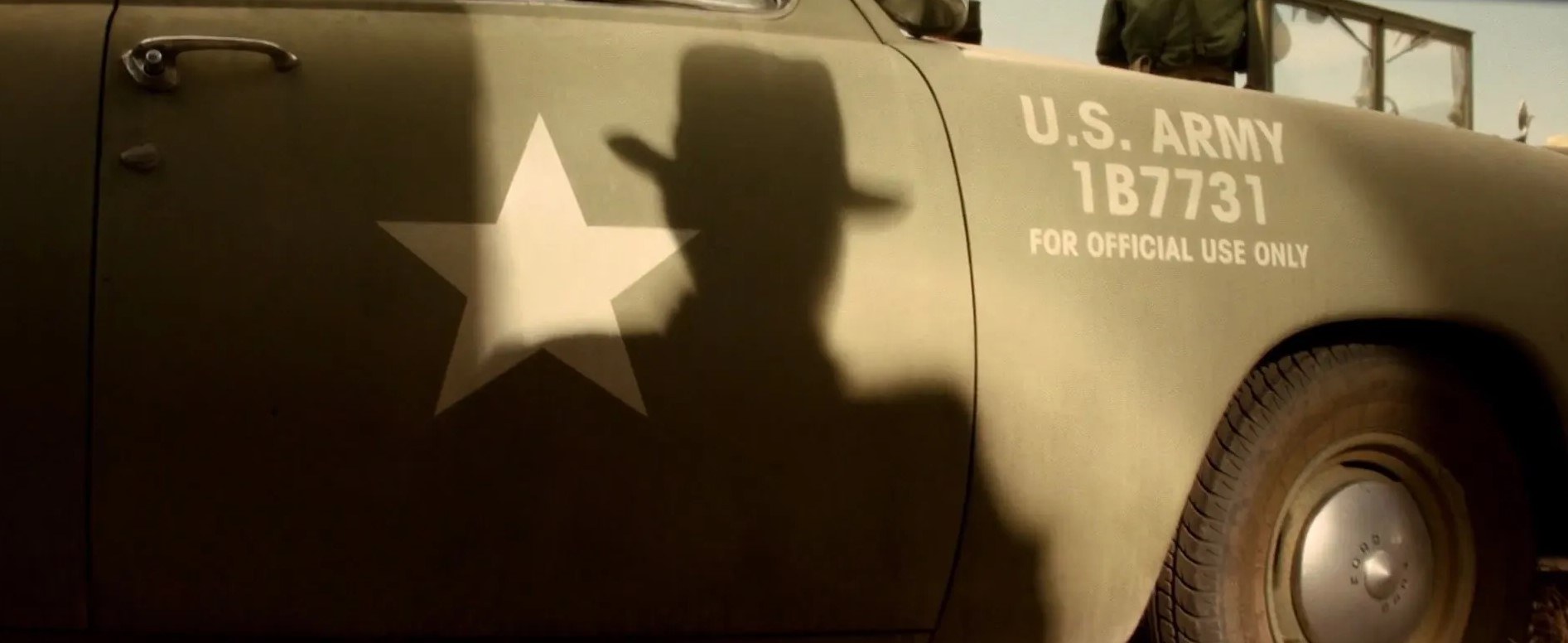

Crystal Skull begins at a secret military base in the desert, where Jones is introduced with a shot that pays homage to the noirish photography of Raiders of the Lost Ark: the camera closes in on Jones’ shoes, then pulls back to reveal his shadow on a car as he dons his signature fedora, then finally dollies around to show his face in a close-up. “It was really beautiful to be able to reintroduce Indy 20 years later,” says Kaminski. Dubin recalls, “Steven made up his mind about that shot on the spur of the moment. It was our first day shooting with Harrison, and Steven was just playing around with the shadow of the fedora and realized what a great introduction that would be. It’s spectacular how Steven can bear the pressure of the whole film and still feel free to go off on a tangent and create a great shot out of nothing but his imagination. It ended up being a very complicated 270-degree camera move, but as usual, we were all up for the challenge.”

A 4K Xenon lamp was used to create the hard shadow on the car in full daylight. “We were in New Mexico, and it was 108°, and all of our electronic lights kept shutting off because of the heat,” recalls Devlin. “So we came up with very elaborate air-conditioning and huts for all of the ballasts, and we made sure the heads and cables were out of the sun. We ended up giving a lot of star treatment to all the electronic lighting because it just hated being in that kind of temperature. Steven just smiled and said, ‘Well, that’s why we used arcs last time!”’

Shortly after Jones is introduced, he is manhandled by some Russian goons and taken into the cavernous secret warehouse that audiences last saw at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark. The set featured endless rows of stacked wooden crates lit from overhead by scoop lights. “That sequence is full of action, and the set was so large you could actually drive a car across it at 25 miles an hour!” recalls Kaminski. “It also called for a lot of smoke, and when you have smoke, you can see light sources, and the whole thing can quickly start looking too theatrical. So our lighting style was a little more frontal rather than backlit. David worked with the art department to create a great, simple overhead lighting setup.”

“We worked at a T5.6 stop, so the overhead lights needed to be super-bright, and we had to have them in the shot, so they had to read at a T16-22,” says Devlin. “We ended up using 4,000-watt practicals that were slightly oversized in relation to the bell housing, but because of the scale of the set, that’s not really noticeable. We had 120 housings made, and each contained four 1,000-watt Narrow Spot Par 64 bulbs. [Chief rigging technician] Mark Mele rigged it all up for us, and we did a lot of extra work so you wouldn’t see all those cables.”

Following this sequence, the film moves to the college where Jones is a part-time professor of archaeology. These scenes were shot at Yale University, and for exteriors, the production altered storefronts and brought in hundreds of period cars and extras. Soon enough, Jones, accompanied by Mutt, gets involved in a high-speed motorcycle chase. At one point, the chase winds through the interior hallway of a library, which also served as one of the production’s standing cover sets in case of inclement weather. “It was a pretty big set, about 700 feet long by 200 feet across, and it had eight large windows,” recalls Devlin. “We brought in six 15-6K Bebee Night Lights for the hallway, and they were a real benefit to us because we could easily move them from location to location for the main unit.”

Several 18Ks outside the windows helped create fill in the massive space. Kaminski recalls, “I was getting small shafts of light, but not as much as I wanted because the glass in the windows was very old and thick. We did our basic overall lighting and put some light in front of the lens to fill in the shadows and create some eye light for the actors. We made it look a little more glamorous than I normally would.”

“Overall, it was great to be part of the legacy of Indiana Jones.”

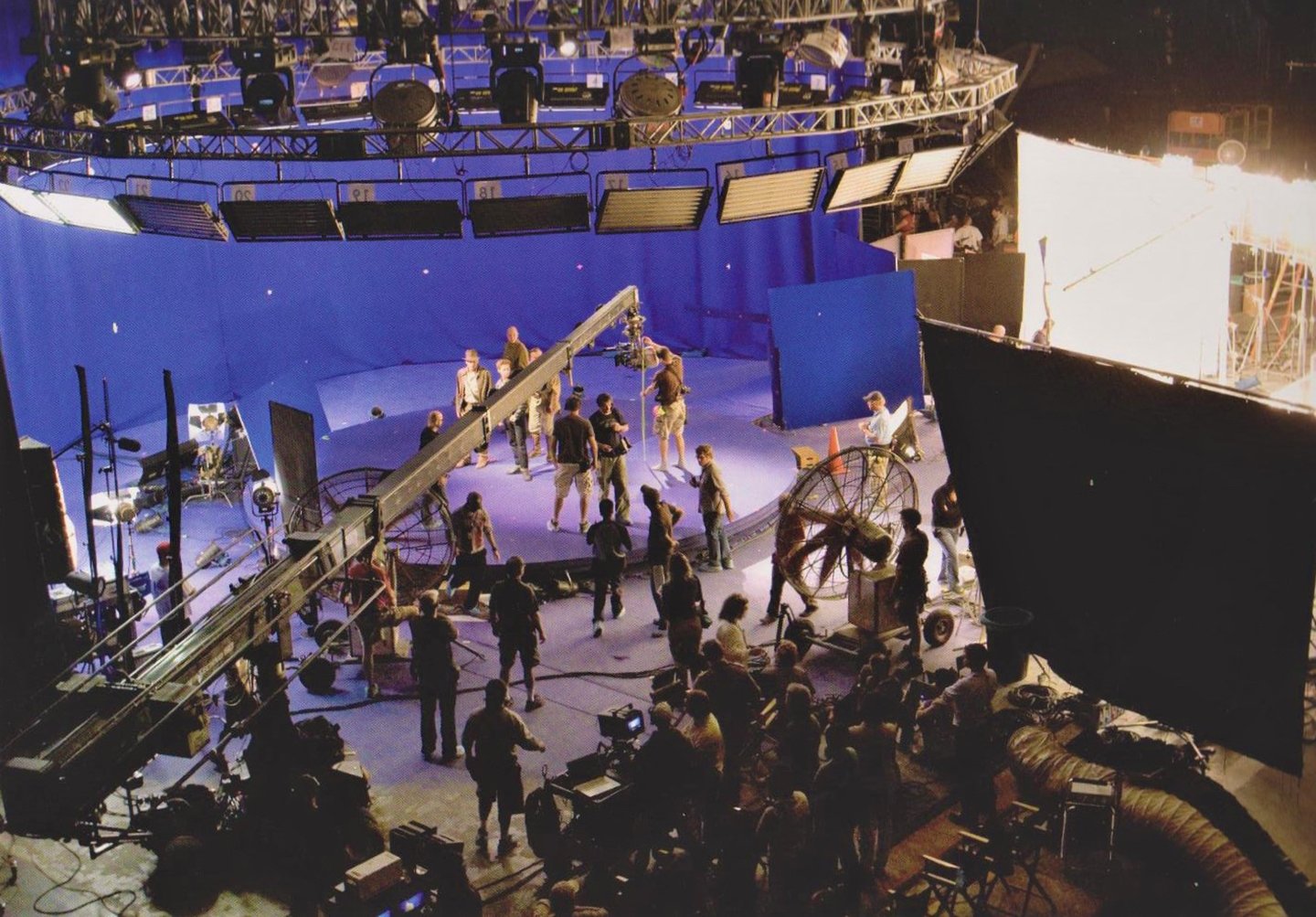

The story then shifts to Peru, where Jones and others make their way to an ancient Mayan temple that is believed to house the Crystal Skull. A car chase in the canopied jungle combines shots filmed on location on the Big Island of Hawaii with bluescreen photography of the actors and vehicles on mechanical gimbals. Kaminski captured traveling shots with a 30' Technocrane mounted on a Camera Cars Unlimited insert car and a waterproof 32' Hydrascope crane with a Wescam XR remote head. The cinematographer worked closely with visual-effects supervisor Pablo Helman of Industrial Light & Magic to maintain visual continuity. “On all of the day exteriors, it was challenging to achieve that glossy, high key Hollywood look because we were constantly trying to overpower the sun,” notes Kaminski. “I often wished I had more contrast between highlights and keys. You start using the sun as your key, and you can’t create a backlight. You’re already at a T22, so to get a stop and half over, you’re at a T40-46! Suddenly, an 18K becomes an eye light.”

Adds Devlin, “For the location work in Hawaii, we established a base stop of T4.5 and then used all sorts of tools to support that, primarily Fresnel lights rigged above the insert car we were driving that lit the trees in the background. We also used a 50K SoftSun on a dimmer as a mobile light for tracking shots; on static shots, we’d just drive up and blast it into the background. To light the deepest parts of the jungle, we also needed a small vehicle that could withstand all the rocks and rutted roads. We used a Toyota truck with putt-putt generators on it and had 1.2K Pars there in different configurations. To light the actors, we used mainly Arri Fresnels, especially the 4K, which I fell in love with on this movie; it’s versatile, it looks great, and it was very reliable despite all the pounding and moisture.”

Back in the studio, Kaminski and his team developed complex mounting and lighting rigs to replicate the look they’d achieved on location in Hawaii. Devlin recalls, “My best boy, Larry Richardson, and I decided to use 5K and 10K beam projectors rigged in a ceiling and going through rotating cucalorises. We also used hundreds of Par cans on dimming cue rolls passing over the stationary vehicles in front of a bluescreen; that created a moving, dappled light on the actors and vehicles, so the ambiance appeared to change as they traveled through the forest.”

Jones and his chums ultimately survive the chase and enter the Mayan temple that serves as the kingdom of the Crystal Skull. There, they soon find themselves running down an enormous spiral staircase with mechanically retracting stairs — a practical, full-sized set built onstage at Sony Studios. The actors performed many of their own stunts as they navigated the 85' stairway, and Kaminski’s camera followed the action on a cable descender. “We had four actors running down the stairs and seven stuntpeople supporting them on wires, so there was no room to hide the lights,” notes Kaminski. “On top of that, the reset was hard because we had to lift everyone back to position. You couldn’t really walk the set; you had to go to the top of the cylinder and come down.”

Dubin recalls, “The centrifugal force kept banging the camera into the wall. It took a lot of work to set the descent speed — too fast and it would hit the floor, too slow and it would miss the action. Jim Kwiatkowski did a great job figuring out how to rig the camera.” Devlin notes, “That set was complicated to light because it was like a big toilet-paper roll made out of steel, and the only lighting could be from the top. We wanted it to get darker as they move down the stairs, but we also wanted to be able to control the exposure. For the overall toplight ambiance, we used 25 12-light MaxiBrutes wired directly into a dimmer with Socapex multicore plugs. We alternated between Medium and Very Narrow bulbs. Roch Dutkowiak, our dimmer-board operator, could selectively turn on the longer-throw bulbs as the actors ran deeper into the cylinder. We also used T5 beam projectors to highlight the rocks and the jaggedness of the stairs.”

Deep inside the temple, Indy and Mutt find themselves in cobwebbed caverns, sets that required an enormous amount of light to create the signature crisp, deep-focus look. “Your perception of light really changes in a set like that,” notes Kaminski. “We were shooting our ‘night’ interiors at T8 to T11. You couldn’t really trust your eyes because when you walked onto the set, it would look very, very bright. We were shooting 5218 and using HMI lights, so all of a sudden, we were putting on an 85 filter.

“If you don’t trust your light meter, you’ll be surprised in a bad way the next day in dailies,” the cinematographer continues. “If you’ve got something at a T2.8 to T4, it’s going to go completely black when you’re shooting a T8 because suddenly that’s 3 stops underexposed.”

Fantastical sci-fi elements come into play as the true nature of the Crystal Skull is revealed — the temple walls and chambers transform to reveal the item’s extraterrestrial origin. This sequence comprises shots of the actors in a set built onstage at Warner Bros. and shots of the actors on a 35'-wide turntable in front of bluescreen that were captured at Downey Studios. “We used Icon 2,500-watt moving yoke lights that were programmed to embellish the spinning sensation in the room,” says Devlin. “We had a piece of truss mounting created in a circle the size of the set, and we used Atomic strobe lights to add a flashing crescendo effect. We also used 28-bulb LumaPanels and chose three different bulb colors; that allowed us to create some pretty radical color shifts as the room comes apart.”

Except for the few weeks the filmmakers spent on location, Kaminski screened dailies at Technicolor in Los Angeles throughout the shoot; Terry Hagger was the dailies color timer. “I haven’t done a movie yet where I didn’t watch dailies, and usually they’re printed,” says Kaminski. “While we were on location, we viewed projected film dailies.”

The cinematographer supervised Crystal Skull's digital intermediate (DI) at EFilm, where he worked with colorist Yvan Lucas. It was Kaminski’s first feature-length DI since The Terminal (AC July ’04). “I see a great advantage in digital timing because I can control the secondary colors, particularly in people’s faces,” he notes. “On this movie, I was constantly fighting different tonalities between the principal actors. With the DI, you can play with tiny changes in red, green and blue in order to conform the flesh tones; you would never be able to do that photochemically.

“I think DI technology has improved immensely, but the trick is to work with someone like Yvan, who really understands conventional timing,” continues Kaminski. “He works on a machine [EWorks] that allows him to apply conventional controls; he’s got red, green and blue, and he’s got points. It’s the same language as photochemical timing, and that not only made me comfortable, it also allowed Terry [Hagger] to be part of the process. This is the first time that the digital image I see matches what I’m getting on a film print, and that’s great.” Taking stock of his contribution to the Indiana Jones mythology, Kaminski muses, “It was a tremendous honor to follow in Douglas Slocombe’s footsteps and continue the visual style he established. At the same time, I was happy to be able to create my own interpretation of the material, because this movie takes place 20 years later. Overall, it was great to be part of the legacy of Indiana Jones.”

2.40:1 Anamorphic 35mm

Panaflex Millenium XL; Arri 435,235

Panavision E-series, C-series and Primo lenses

Kodak Vision2 250D 5205, 500T 5218

Digital Intermediate

Printed on — Kodak Vision Premier 2393

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.