A Lifetime of Achievement: Conrad Hall, ASC

“Movies are entertainment. They are a diversion from reality. But they can also make a lasting impression about the human condition.”

This profile was originally published in AC, Feb. 1994. Some images are additional or alternate.

The ASC Lifetime Achievement Award was initiated in 1988 to recognize cinematographers who have compiled significant bodies of work which have made a lasting impression. Previous winners were George Folsey, Joe Biroc, Stanley Cortez, Charles Lang, Philip Lathrop, and Haskell Wexler. The 1994 winner is Conrad Hall, ASC.

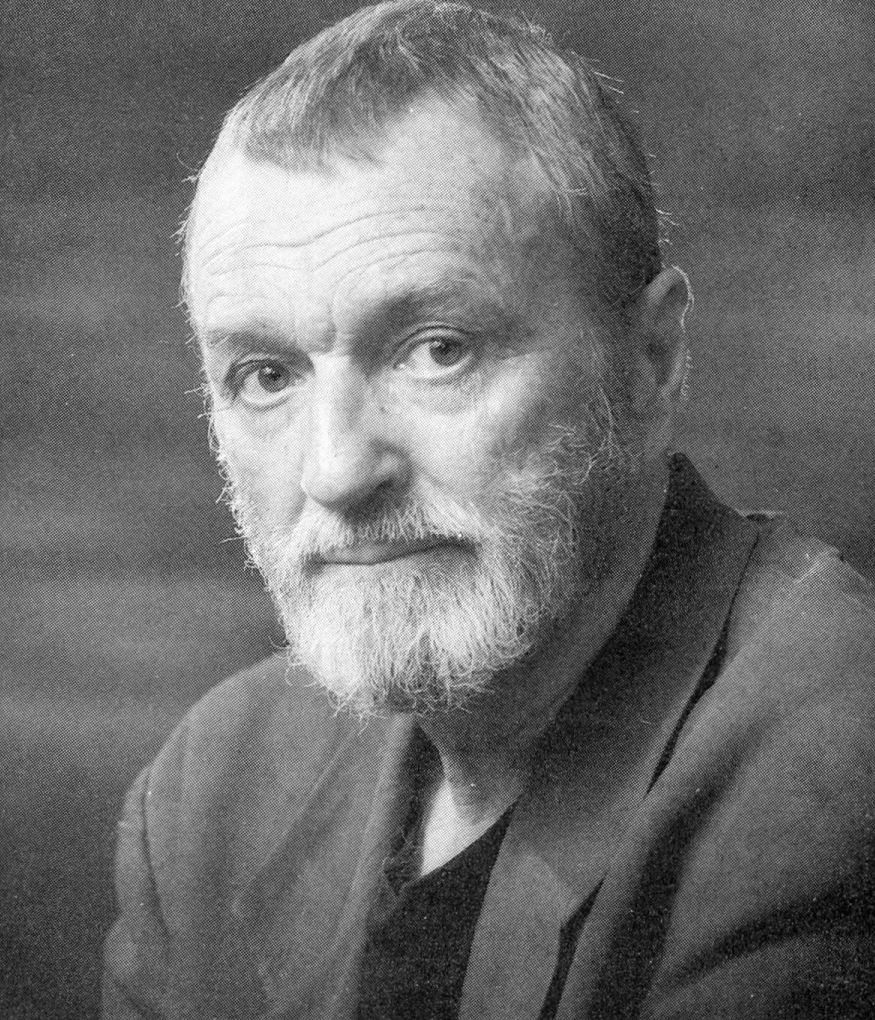

Conrad Hall, ASC was stunned when he learned that he had been chosen to receive the 1994 ASC Lifetime Achievement Award. To cinema aficionados, however, the choice is perfectly logical. Hall has spent his entire career doggedly pursuing what he terms "the happy accident, the magic moment," and his cinematic divining rod has produced some of film history's most memorable images. Along the way, Hall's uncompromising commitment to artistry — and willingness to take risks in pursuit of that artistry — has earned him the respect and admiration of his peers, who occupy filmmaking's penthouse echelon.

“Cinematography is infinite in its possibilities — much more so than music or language. There are infinite shadings of light and shadows and colors; it’s an extraordinarily subtle language. Figuring out how to speak that language is a lifetime job.”

"It took a while for me to grasp that my colleagues believe I have made an impact on the history of cinema," he says of his Lifetime Achievement honor. "Billions of people have seen and been influenced by movies in the short history of this industry. My peers say I have made a difference. That means more to me than winning an Oscar."

Still, he says, the honor somehow feels premature. How could he receive the ultimate recognition when his body of work is still evolving? "I'm too young," the 67-year-old cinematographer insists. "I hope I'm still shooting when I'm 80."

While Hall maintains that his best days are still ahead of him, he has already accumulated an impressive and influential body of work. He won an Oscar in 1969 for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and earned other nominations for Morituri, The Professionals, In Cold Blood, The Day of the Locust and Tequila Sunrise. The latter film also garnered Hall the 1988 ASC Outstanding Achievement Award for Cinematography. The cinematographer's other credits include such highly regarded pictures as Cool Hand Luke, Harper, Electra Glide in Blue, Fat City, Marathon Man and Black Widow.

Hall was in the first wave of a new generation of cinematographers who broke into the industry during the 1950s and ’60s. Given his background, however, cinematography was an unlikely vocation.

His father was James Norman Hall, an ace pilot and captain in the Lafayette Escadrille, which fought for France during World War I. After the war, the elder Hall and fellow volunteer Charles Nordhoff were asked to write a history of the unit. Searching for a quiet place where they could concentrate, the pair found solitude — and a new world — in Tahiti. Instead of writing about the Lafayette Escadrille, Hall and Nordhoff completed a novel they called Mutiny on the Bounty.

James Norman Hall settled in Tahiti, where he wed the descendant of a marriage between a Tahitian lady and an American English sea captain. The couple's son, Conrad, grew up on the island in a cloistered literary environment. He never had a camera or took a picture, and going to see movies was an exotic concept. During his teens, Hall was sent to an exclusive prep school in Santa Barbara. Afterward, he enrolled at USC with instructions from his father to find a career. But how do you measure up to a father who fought aerial duels with the legendary Red Baron and went on to write a classic novel?

Hall enrolled in the journalism program, but it was a short-lived experience. "My first semester, I got a D in creative writing," he recalls. He decided to choose another field, leafing through the As and Bs in the curriculum catalog before settling on cinema. His decision to enroll in the cinema program wasn't a frivolous one, however; movies were a relatively new art form, and Hall thought it could be interesting to get in on the ground floor.

His timing couldn't have been better. USC's cinema school was headed by Slavko Vorkapitch, a Yugoslavian writer who had migrated to Hollywood in 1922. Vorkapitch had done some screenwriting but mostly was known for the power of his visual montages. He lent his talents to several features, including I Take This Woman, Crime Without Passion, and Shopworn Angel.

Vorkapitch had an unforgiving disdain for "photoplays," which was how he characterized most Hollywood films. "He was like a surrogate father," says Hall. "He had the spirit and soul of an artist. He taught me that filmmaking was a new visual language. He taught the principles, and left the rest up to us."

The professor found a disciple in Hall. "I can still recall the thrill of shooting my first film," Hall recalls. "It was a scene of a car coming to a stop sign and then driving off. Our allotment for the semester was only 100 feet of 16mm black-and-white film. I knew exactly how I wanted it to play, but you are never sure it will work until you watch the projected images reflect off the screen. When I saw the film for the first time, I became hooked on the power of visual imagery and its effectiveness in telling a story."

Filmmakers visited the students regularly. On one such occasion, John Huston showed them dailies of The Red Badge of Courage. Orson Welles was another influence on Hall, as were many screenwriters Vorkapitch recruited to talk with the students.

After graduation, Hall discovered that a cinema school degree didn't unlock any doors in Hollywood. He confronted the classic "Catch 22" situation: you couldn't work on a camera crew unless you were on the International Photographers Guild roster, but you couldn't get on the roster without experience. Given these realities, the odds against success were nearly insurmountable.

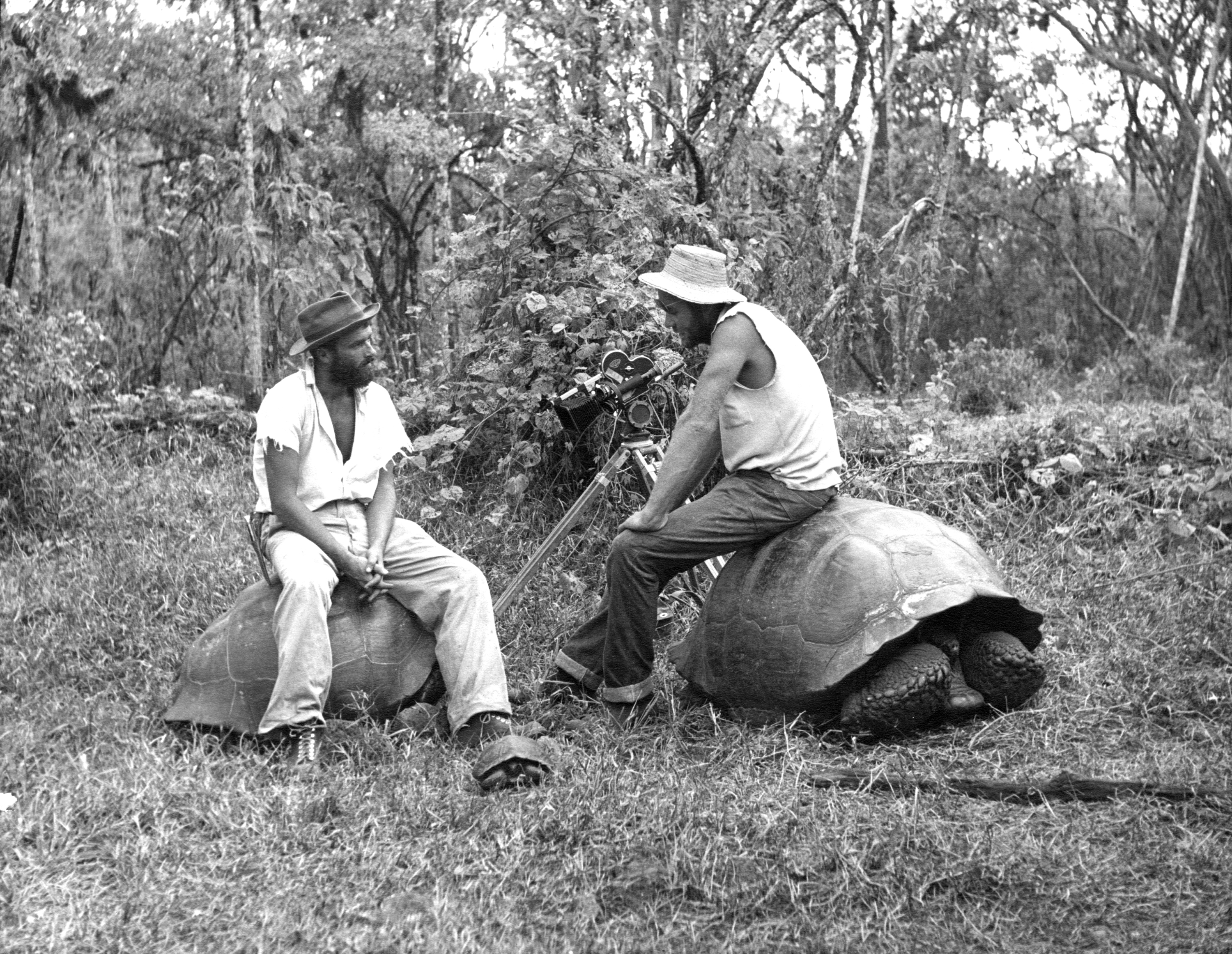

Hall was determined to beat those odds. He and two classmates, Marvin Weinstein and Jack Couffer, organized Canyon Films. The trio produced documentaries, commercials and industrial films, but there were long periods when they mainly dreamed about the future. Hall shot commercials and industrial films and did some pickup shots for features.

Canyon Films eventually purchased a short story entitled My Brother Down There with the idea of turning it into a feature film. The three partners collaborated on the script. Then they put slips of paper into a hat. One said "producer," another "director," and the third read "cameraman."

Hall pulled camera duty, and the luck of the draw helped him get into the International Photographers Guild. "In order to appease the union, we made a deal to hire a guild cameraman," Hall says. "I shot the picture, but the Guild cameraman got the screen credit. I was given a credit as a visual consultant." The film was released by United Artists under the title Running Target.

Afterward, the partners went their separate ways, and Hall was allowed to join the guild.

Once in the guild, Hall worked as a camera assistant with Burnie Guffey, ASC, Ernie Haller, ASC, Hal Mohr, ASC and Ted McCord, ASC. After a year with McCord, Hall was upgraded to operator. The young operator was working on a TV series called Stoney Burke when McCord got sick; Hall was asked to take over. The next year, he filmed The Outer Limits, shooting 15 episodes of the sci-fi-series.

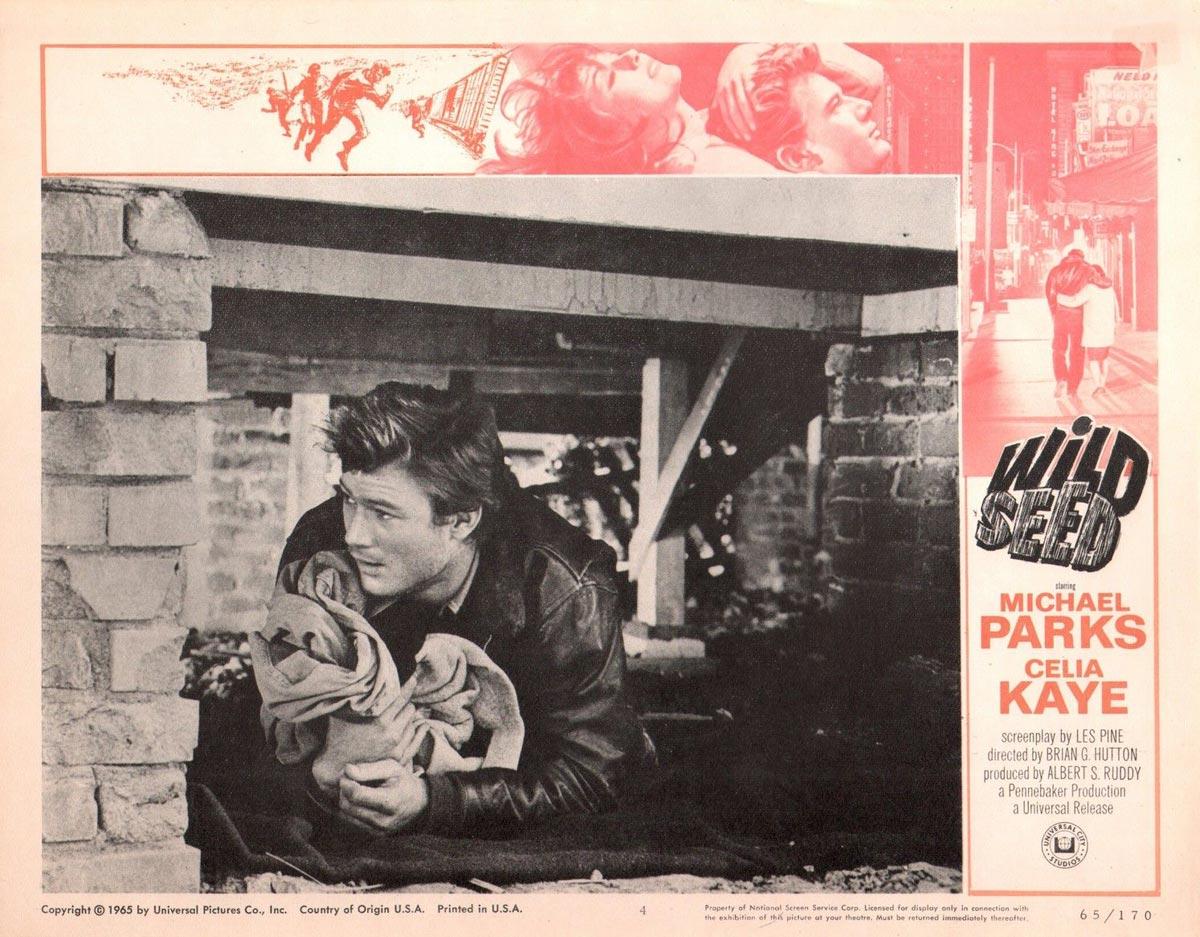

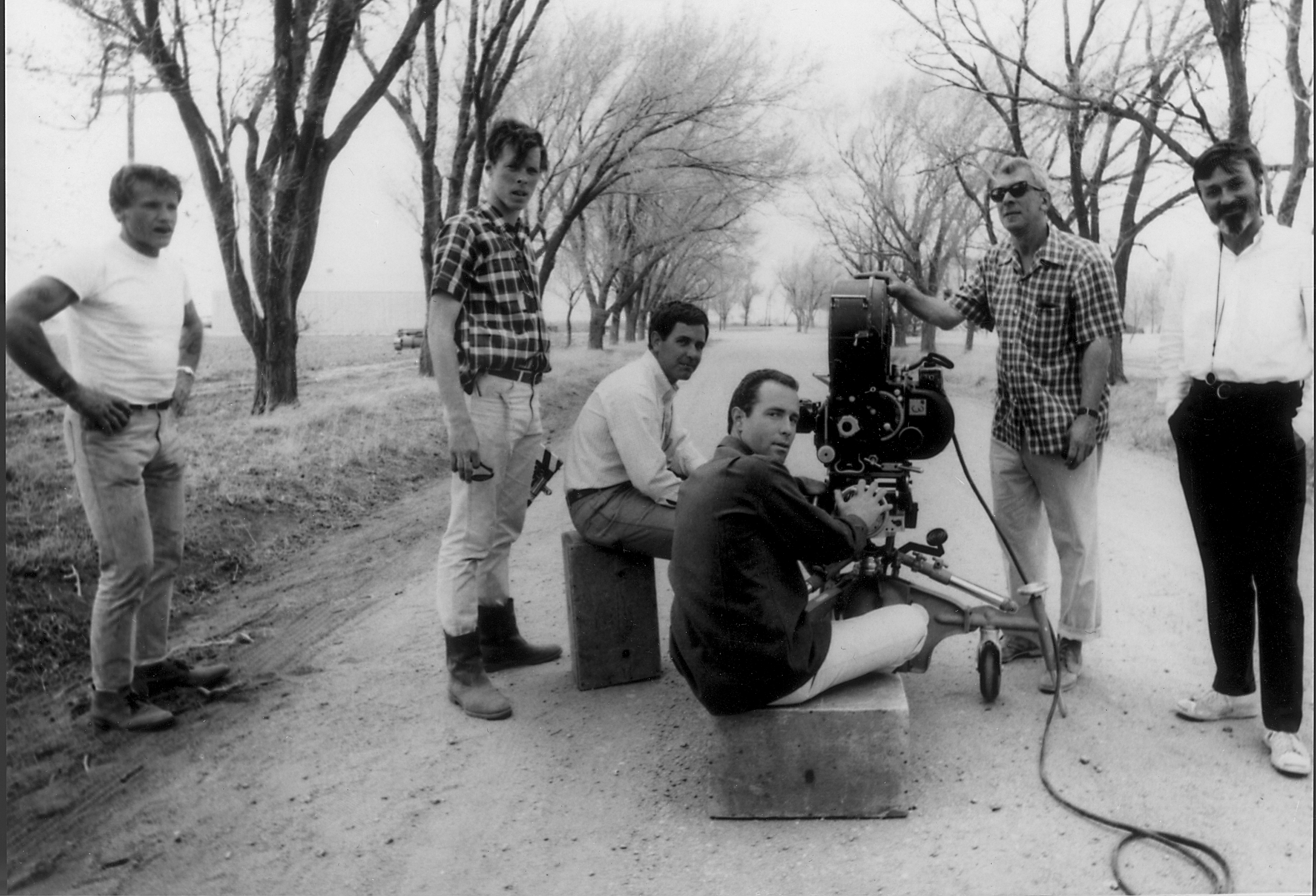

In 1964, Hall shot his first union feature, The Wild Seed. The black-and-white production was filmed in 24 days on a $286,000 budget. Recalling the harried pace of the production, Hall cracks, "In those days it seemed like plenty of time and money."

Veteran producer Tom Shaw, who worked with Hall on The Wild Seed and many subsequent outings, says that Hall's quick thinking and on-the-spot improvisations were a wonder to behold: "It was one of the best damn jobs I ever saw anyone do in my life. We made that film in 24 days, but it seemed like 24 minutes! And it turned out so well, I'd put it up against almost anything, even though we made it for about 20 cents. Connie did a great job with very little; at one point, we were shooting the interior of a boxcar, and both generators went out. He lit the whole thing with the reflectors, and it was beautiful. He's very inventive and imaginative. I never knew Connie before that movie, but I was so impressed by what he accomplished with no resources that I got him for the next film I worked on, The Professionals.”

Later in 1965, Hall earned his first Oscar nomination, for Morituri. In 1966, he shot Incubus, Harper and then The Professionals. Harper was his first color film, but he remembers shooting it as if it were black-and-white. "I was much more concerned with the importance of camera movement," he says.

The Professionals was his first film with director Richard Brooks and earned the cinematographer his second Oscar nomination. At the time The Professionals was being made, the industry was benefitting from an amaz¬ ing influx of talent, as evidenced by the fact that Hall's crew on the film included future photographic wizards William Fraker and Jordan Cronenweth.

Very early in preparation, Brooks cautioned Hall that he was going to be tempted to help him direct. He then pointed out, in a style befitting the film's Western milieu, that there was only room for one sheriff in town. Hall, a plain talker himself, respected the filmmaker's frankness, and the pair soon developed a fertile artistic rapport.

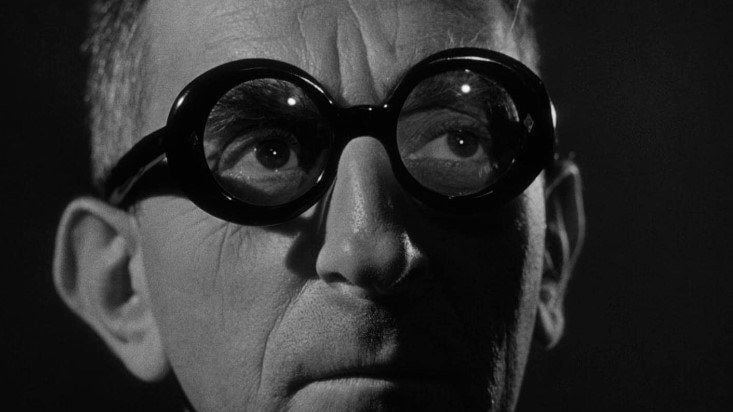

The effectiveness of the Brooks/Hall teaming was reinforced in 1967, when Hall collected an Oscar nomination for the third consecutive year for In Cold Blood. In seeking to imbue the film with an intense, documentary feel, Brooks opted to shoot on the actual locations of the true story, which recounted the brutal slaying of an upstanding Kansas family.

Hall and Brooks originally wanted to shoot the picture in a 1.85:1 hard-matte format to ensure that it would be projected properly. "I didn't want too much or too little headroom," Hall notes. "I wanted people to see things just the way I wanted to show them." When Columbia Studios objected, however, the duo opted to shoot in the 2.35:1 anamorphic format to preserve the precision at the top and bottom of the frame. Hall reasoned that if the edges of his frame were cut off during projection, the compositions would approximate the 1.85:1 ratio he had originally desired.

While the film is filled with stunning images, perhaps the most unforgettable sequence occurs when Robert Blake's killer roams through the family's dark house with a flashlight. After lighting to provide a certain amount of basic visibility for the scene, Hall lent the sequence a chilling ambiance of dread by adroitly exploiting the everchanging light levels produced by the flashlight's bouncing beam.

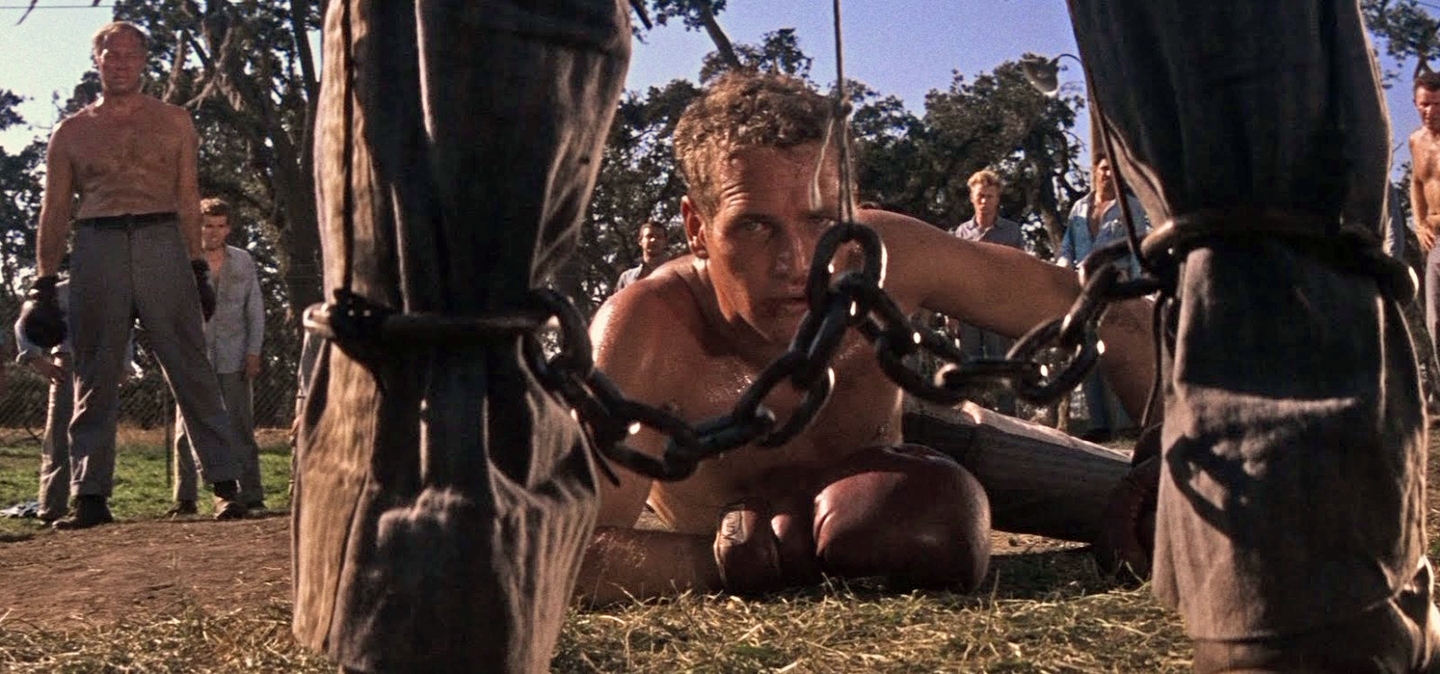

That same year, Hall added Cool Hand Luke and Divorce American Style to his body of work. In 1968, he shot the aptly titled Hell in the Pacific: the production was a logistical miracle or a nightmare, depending on your perspective. "We spent eight months shooting on a remote island," Hall says. "We took a boat for 20 miles every day, switched to an amphibious duck, and finally waded in, carrying the equipment over a reef. After all that work, I think they used stock footage in the final scene."

Hall earned the Oscar for Butch Cassidy in 1969, filming Willy Boy is Here and Brooks' The Happy Ending in the same year. On both Butch Cassidy and Willy Boy, Hall experimented with overexposing the negative and printing it back down in order to mute strong primary colors. Although he also tried using fog filters and other lab techniques to accomplish this end, he found overexposing to be the most effective method of "destroying" the color and sharpness of the film's images so that they would more closely resemble the look of real life.

In 1972, Hall collaborated with John Huston on Fat City, a raw exploration of life in the seamy world of boxing. Before the filmmakers began planning the photographic approach, Huston called Hall and production designer Richard Sylbert into his motel room to solicit their opinions on the film's subject matter. The trio concluded that the film was about life going down the drain before you could put the plug in.

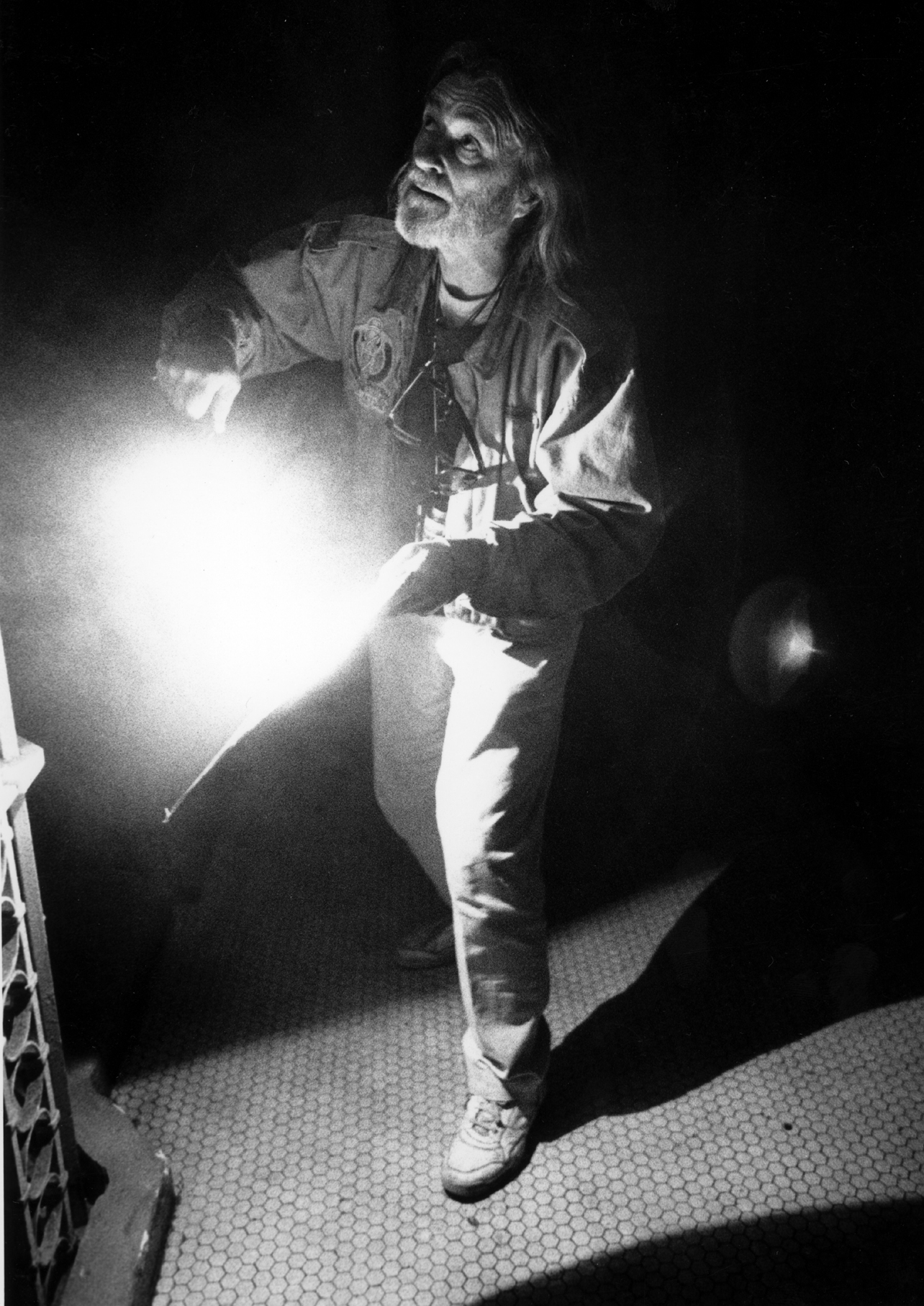

While contemplating the look of the film, Hall set up a camper/truck in the Skid Row areas of Stockton, California, where the homeless denizens were barely surviving their subsistence existence. He cruised the streets looking for examples of life "running down the drain," documenting his observations with a hidden camera. Hall, Huston and the actors studied the film and used it as a model for mimicking reality. The success of this approach is evident in the completed film, which has a grainy texture that never allows the audience to forget the harshness of the reality depicted in the story.

There were times when Hall called Fat City the film nearest and dearest to his heart. It bothered him that the film wasn't a commercial success. He felt it deserved an audience, and for years afterward, he screened Fat City at schools and analyzed why it hadn't succeeded at the box office.

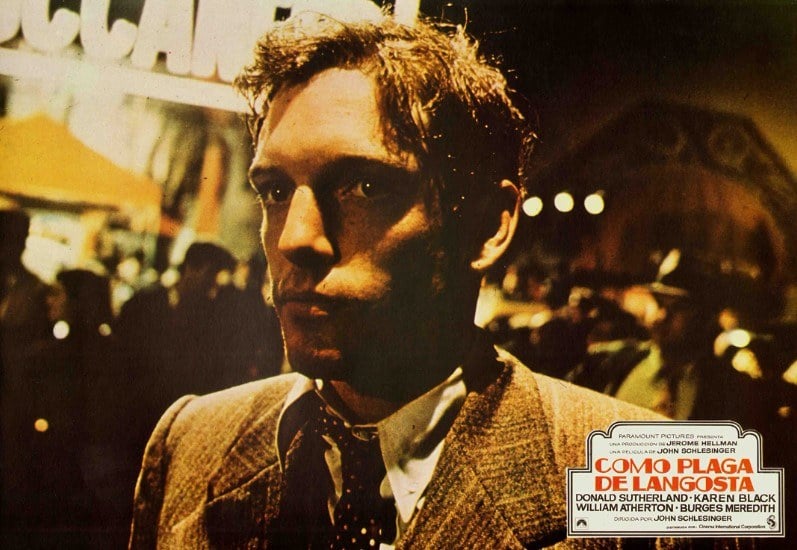

Hall shot four other films during that period: Electra Glide in Blue in 1973, Smile and the Oscar-nominated The Day of the Locust in 1975, and Marathon Man in 1976. On the latter two pictures, Hall made the acquaintance of director John Schlesinger, who recalls the collaboration fondly: "Connie is one of the very best cameramen I've ever worked with, although he can be quite a cantankerous character at times. He's very critical and very involved with the entire process of filmmaking, so he certainly keeps directors up to the mark. He's committed to excellence, and he has a great knowledge of what the camera can do. We had a wonderful time on Day of the Locust, which was an absolute joy to make. Connie and I discussed the look in great detail before shooting and decided to balance the darkness of the story with a hot, muggy background glow. One of Connie's greatest attributes is his ability to find and convey the mood of a story. Many cinematographers will simply set up the lights and let it go at that, but Connie really attempts to get at the heart of the subject matter."

While working on Marathon Man with Hall, however, Schlesinger noticed a change in the cinematographer's demeanor. "He seemed less happy on that picture; I think he was getting antsy about wanting to direct his own films. I detected a restlessness and impatience in him, but he still did an excellent job."

Marathon Man ended Hall's string of 18 films made over 12 years. He would not shoot another feature for 11 years. Determined to pursue other avenues of endeavor, Hall formed a commercial production company with Haskell Wexler, ASC and directed and shot hundreds of ads. His shooting was experimental at times, and it also gave him an opportunity to observe other cinematographers at work. But to many, the move was like Bach eschewing symphonies in favor of country music.

Hall says that he spent much of his self-imposed "sabbatical" writing an original script, as well as another based on the William Faulkner novel The Wild Palms. As Schlesinger had sensed, he was determined to direct his own film, to control the filmmaking process from beginning to end. His longtime wish may finally be granted in the near future; Hall recently struck a handshake agreement with producer Scott Rudin in which he promised to shoot Searching for Bobby Fischer if Rudin would give him a deal on The Wild Palms.

[While Hall did shoot Bobby Fischer, he never direct The Wild Palms or any other feature]

Looking back on his long hiatus, Hall reflects, "In some ways, it was the best time of my life. I have no regrets. I was very happy sitting alone at a dining room table, writing a script. It was something I had to do. It's something I still have to finish. Photography is a very important part of my life. But at heart, I am more than a cinematographer. I'm a filmmaker."

Hall adds that he also managed to enhance his knowledge of photography by collaborating on commercials. "Every cinematographer I worked with had his own way of solving problems," Hall says. "I directed many commercials shot by George Folsey. He would call for innumerable lights until, finally, the gaffer would say there was nothing left. With all of those units, George was always creating simplicity. The complexity of his lighting was never apparent in the images. He lit with little simple strokes of light. Others used broader strokes with bigger and fewer units. If you paid attention, you learned by osmosis. The truth is that every experience, every feeling, and every film you see becomes part of the sensibilities you apply to making a movie."

Hall returned to the world of feature films in 1987 to shoot Black Widow, a lush film noir effort. Robert Towne, a director he'd wanted to work with, then got Hall interested in shooting Tequila Sunrise. Unfortunately, the studio had agreed to shoot the picture with a non-union crew, precluding Hall's participation. The cinematographer instead accepted an offer to photograph the Christmas comedy Scrooged, but personality conflicts led to his dismissal from the picture.

Hall was back on his island in Tahiti, "watching the coconuts fall," when Towne called to report that the Tequila Sunrise film company had finally signed a union contract after five days of shooting. The director entreated him to return to work on the picture, citing an aesthetic conflict with the original cinematographer, who had supposedly told Towne that he didn't want to continue on the picture. Mindful of professional protocol, Hall told Towne he would only take over if the other cinematographer gave him his blessing. After having lunch with the disgruntled cameraman, Hall finally agreed to take up the reins.

"I didn't know what Robert was thinking, but Casablanca was on my mind," Hall says. "I saw Tequila Sunrise as a romantic picture with complex, bigger-than-life characters. There was a lot of fog and wet streets. It reminded me of the contrast characteristic of the romantic black-and-white films made by Old Hollywood."

“Everybody knows that he’s great, but in some weird way, I still think he’s underrated.”

— Robert Towne

The film's colors are lush and deeply saturated, but Hall approached Tequila Sunrise as he would a black-and-white film. He interpreted daylight exteriors on the seashore as glaring white light, and nights as lush, pure blacks. Much of the film involved night exteriors shot on yachts, docks, a bridge, and other similar locations.

Hall watched and listened while Towne led the cast through rehearsals. Then they discussed how each scene should be visualized. Hall used a "quiet camera" with very little movement, even on the longest dialogue scenes. He would shoot over someone's shoulder, and then inch in closer until he brought the audience into intimate eye-to-eye contact with the character. The cast provided the motion, and he probed the darkness with the aid of fast Primo lenses and the 500-speed Eastman 5294 film.

Whenever possible, Hall lit from practicals. In one restaurant scene, he simply cut the backs off of lamp shades on the set and replaced them with diffusion material. Hall augmented the ambiance by lighting through sheets of bleached muslin, creating a very soft, non-descript light, seemingly emitted by the practicals.

"Contrast is what makes photography interesting," he says, "and there is more than one way to create it. You can flat-light someone and keep the background dark. You can cross-light the cast and keep strong shadows on their faces. Or you can backlight the cast and use more somber and gentler light to bring out their skin tones."

He used all of these techniques while filming Tequila Sunrise. Sometimes he used a light net or a Superfrost filter on the camera lens. For night exteriors, he generated thousands of cubic feet of fog. Then he backlit characters and modeled their faces with very soft light, and used strong cross- or front-light to create contrast between the actors and background.

A twilight shot of swings in a park has always generated much interest among cinematographers, who invariably ask Hall how many nights he needed to get it right. Hall relates that he shot the sequence like a commercial; the swings were portable, and the crew merely shifted their positions so the setting sun was always in the right place.

Recalling the Tequila shoot recently, Towne credited Hall with both creative genius and unflagging dedication. "Everybody knows that he's great, but in some weird way, I still think he's underrated. He's a man with the passion and enthusiasm of a kid; he has the generosity, simplicity and insightfulness of the rarest gifted people. I would never bother to tell Conrad what kinds of shots to make; he would just say to me, 'Tell me what you see.' He'd listen and then say, 'OK, I've got it.' He really understands where the dramatic fulcrums are in the scene. He's also uncommonly sensitive to the performances of the actors: he knows when somebody's 'on' or 'off,' and he innately understands where people should be in the frame.

"One of my favorite memories from that shoot involves Connie," Towne adds. "We had 40 nights on the movie over a 66-day schedule, and it reached a point where he was so exhausted it looked like he was asleep during retakes. He was sitting in a chair, and his head was just jerking back and forth from fatigue. I thought to myself, 'Well, I shouldn't bother him, the retakes are going badly anyway.' Then, after the third take, he suddenly opened one fish eye and said, 'I don't know why the f—k you're bothering to shoot this; it's just as bad as it was the first time.' Even in his sleep, he knew it! Finally, on the fourth take, it got good, and his eyes opened as if by magic. The man is uncanny."

Hall's experience on Tequila Sunrise reignited his passion for photography. His subsequent films included Class Action, Jennifer 8 and Searching for Bobby Fischer. A third-time remake of Love Affair, starring Warren Beatty and Annette Bening, is still in postproduction.

“He makes the camera a privileged viewer of the narrative; there's only one place for the camera as far as Connie is concerned, and that’s the right place.”

— Bruce Robinson

Bruce Robinson, the director of Jennifer 8, says of his time with Hall, "It was the best creative relationship I've ever had. He wouldn't ever let you make a mistake from a technical point of view; he truly knows everything there is to know about filmmaking, and he's very generous with that knowledge without ever making you feel as if you're a poor relative. He makes the camera a privileged viewer of the narrative; there's only one place for the camera as far as Connie is concerned, and that's the right place. While we were working, I said to him at one point, 'How do you know where to put the camera?' And he replied, 'I point the camera at the story.'"

On Bobby Fischer, Hall lent a guiding hand to first-time director Steve Zaillian, who reports that the veteran's ideas on the filmmaking process made a lasting impression. "Since it was my first directing job, I had a tendency to want to plan everything out, and I did that for the first few weeks. But Connie taught me the value in being open to the unexpected. When we showed up on the set, he'd ask me what scene we were doing that day, and then he'd force me to tell him what I thought it was about. And we wouldn't even talk about how to shoot it until we'd seen a rehearsal. It was a little scary to work that way, not knowing exactly what we were going to do, but it was also exhilarating. His approach to the film was his approach to life: whatever you're working on at the moment is of paramount importance, regardless of its relative size or scope. If I were to direct another film, I'd feel lost without him; I depended on him that much."

Hall confirms that his own approach to cinematography is primarily instinct-driven. But those instincts are based on a lifetime of impressions stored in his visual memory. He frequently compares himself to a river fed by many small streams that represent the different experiences in his life.

Analyzing the contemporary world of cinematography, Hall notes that rapid improvements in technology are changing the art itself. "With today's fast films," he says, "you can light the way your eye sees the scene. You can abuse the film and create subtleties in contrast with light and exposure, diffusion and filters. That's what makes it an art. Cinematography is infinite in its possibilities — much more so than music or language. There are infinite shadings of light and shadows and colors; it's an extraordinarily subtle language. Figuring out how to speak that language is a lifetime job. You are always a student, never a master. You have to keep moving forward."

While Hall appreciates the new creative options presented by technological advances, he has also noted a few detrimental side effects. In his opinion, the worst invention in modern filmmaking is video assist. "There are a lot of directors who are knowledgeable about images, and others who aren't," he says. "In the latter scenario, video assist interferes with the collaborative process. You have two dozen people looking at an image on a monitor and saying, 'What if we tried this?' Suddenly, everybody has an opinion."

Hall's ire is not fueled by a desire for control, but by his perception that such toys could drain the passion from the art form. In explaining his position on the issue, he limns a creed that filmmakers everywhere should take to heart.

"This isn't a job for me," he says. "It never has been. It has always been a way of life. I realize that every picture isn't a work of art. But you still have an awesome responsibility, because you are helping to create something which might influence the thinking of millions of people. Movies are entertainment. They are a diversion from reality. But they can also make a lasting impression about the human condition."

Hall was later nominated by the Academy for his work on Bobby Fischer, and again in 1999 when he reteamed with Steven Zaillian for A Class Action. The following year, Hall won the Oscar for American Beauty, and then won his third Oscar with his tenth and final nomination, in 2003, for Road to Perdition. Hall passed away on Jan. 4, 2003, at the age of 76 just weeks before the Oscars ceremony. The award was presented posthumously, accepted by his son, cinematographer Conrad W. Hall.