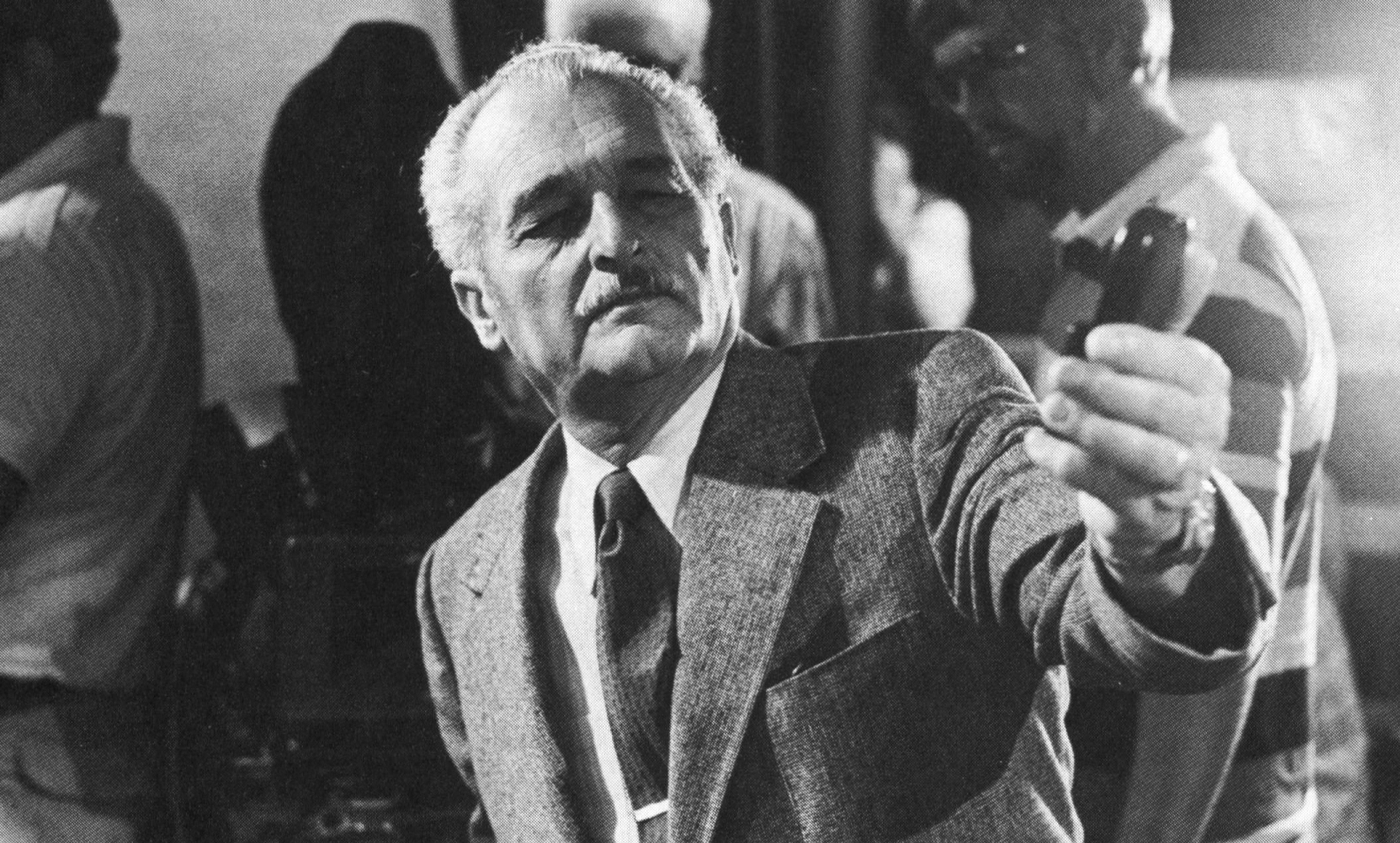

Philip H. Lathrop, ASC Steps into the Spotlight

The cinematographer is honored with the Society’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

This article was originally published in AC Feb. 1992.

Phil Lathrop, ASC, has had the kind of career that most cameramen dream about. He has been nominated for two Oscars, has won a pair of Emmys after being nominated five times, and has worked with some of the industry's top directors, including Orson Welles, Francis Ford Coppola, Sam Peckinpah, Sydney Pollack, Norman Jewison, John Boorman and Blake Edwards.

In recognition of his outstanding career, the American Society of Cinematographers will honor Lathrop with its 1992 Lifetime Achievement Award, given in recognition of a body of work that has made a meaningful and significant impact on the art form. Lathrop is joining an elite group that includes ASC members George Folsey (1987), Joe Biroc (1988), Stanley Cortez (1989) and Charles B. Lang, Jr. (1990).

Lathrop has some 65 feature credits. The Americanization of Emily and Earthquake earned Oscar nominations. Other memorable features include Lonely Are the Brave, Experiment in Terror, Days of Wine and Roses, The Pink Panther, Cincinnati Kid, Point Blank, Finian's Rainbow, What Did You Do in the War Daddy?, I Love You Alice B. Toklas!, The Illustrated Man, The Gypsy Moths, The Hawaiians, They Shoot Horses Don't They?, Portnoy's Complaint, Marne and The Killer Elite.

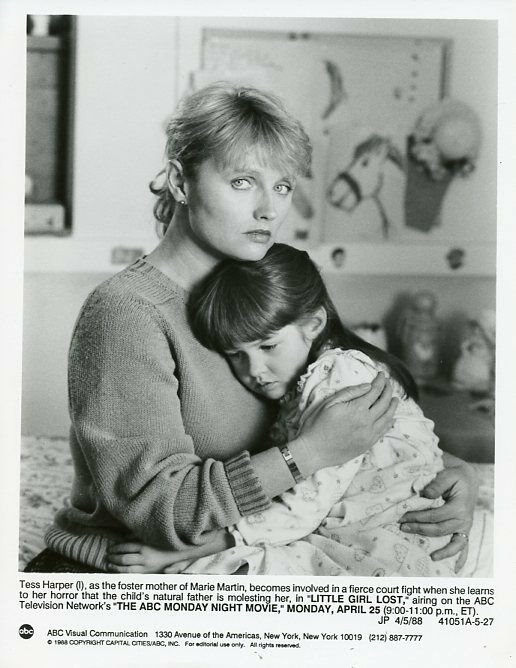

During the 1980s, Lathrop's work included eight television movies of the week. He earned Emmys for two of them, Malice in Wonderland and Christmas Snow, and nominations for three others, Celebrity, Picking Up the Pieces, and Little Girl Lost.

Lathrop was bom in Merced, California. He grew up in the San Fernando Valley when it was a rural appendage to Los Angeles. His father farmed fruit and vegetables, and his mother worked at a motion picture lab on the Universal Studios lot, breaking down dailies.

Lathrop took the first step on his career path when he was only 10 years old. He and a friend spent many weekends watching movies being made at Universal Studios and were there in 1928 when Harry Pollard was directing the original Show Boat, starring Laura la Plante and Joseph Schildkraut.

"We would run around the Show Boat set when they weren't shooting," he says. "I remember thinking that making movies must be a great way to spend your life. But I never thought that was possible for me."

Eight years later, Lathrop was working as a film loader in the camera department at Universal Studios while director James Whale was shooting a remake of Showboat, starring Irene Dunne, Paul Robeson and Allan Jones.

"There weren't a lot of jobs available when I was getting out of school," Lathrop explains. "There was still a depression. I had a friend whose father was head of the camera department at Universal Studios. He asked if I wanted to work as an assistant cameraman. It paid $50 a week. That was a fortune in those days."

Cinematographers were under contract, but crew members were only paid when they were working. Lathrop asked for a job in the camera department as a film loader. "I was getting married, so I needed a steady job," he says. He worked nights, loading cameras for the studio's contract cameramen. Milt Krasner, Joe Valentine, Hal Mohr, Woody Burdell and George Robinson were all working on the lot around that period.

"I got to know all of them," Lathrop says. "I took care of their equipment and loaded their cameras every night. During the day, I watched them shoot. After a couple of years, Joe Valentine asked me to work on his crew." Lathrop was 20 at the time.

He started working with Valentine as a second assistant in 1938. After a couple of pictures, he was promoted to assistant cameraman. "Joe wanted to make me an operator right away because Arthur Arling was leaving his crew to work for Technicolor. But I told him I wanted to spend five years working as an assistant until I knew everything about it. That was before there were reflex cameras. There was a lot to learn."

It was close to 10 years before Lathrop got another chance to become an operator. "There weren't any opportunities," he says. 'I worked on a couple of pictures with Lucien Ballard. But mostly I worked with Joe until he left the studio. Then I worked on Russ Metty's crew as an assistant cameraman. After a couple of years, he made me an operator."

Lathrop spent nine years with Metty. "He let me work with the directors," Lathrop says. "I spoke with them and laid out shots. Russ really gave me a chance to learn. After about five years, I realized I was at a point where I knew everything about operating a camera. So I started doing things a little differently. I panned in different directions and experimented with composition. Russ gave me a lot of things to do with the camera. He helped a lot of people that way."

His last picture with Metty was Touch of Evil, directed by Orson Welles. That experience, Lathrop says, was like going to film school. "Orson laid out some terrific shots," he recalls. "People still ask me about things Orson did on Touch of Evil.”

The film starred Welles as a crooked police inspector in a Mexican border town. Its bravura opening sequence began the show with a bang — literally. One of the first shots reveals someone placing a bomb in the back end of a car parked behind a liquor store.

Welles utilized long takes throughout the film, but this first sequence stole the show. Cramming the frame with the border town's seedy ambiance, the director timed the on-screen events precisely, building the suspense to a thrilling peak.

There were no zoom lenses in 1957, so Lathrop operated the camera from a big crane. The camera pulls back and moves up above the action as the car turns and drives down an alley along the other side of the store. It stays about a block away on a long shot, as if afraid to get too close to the ticking bomb; Welles frequently used such tactics to send the audience subliminal visual cues.

As the sequence continues, uninterrupted, the car drives around another corner and overtakes newlyweds Janet Leigh and Charlton Heston as they walk down the street. It stops at a border checkpoint, where the driver showed a guard his paperwork. By this point, Welles has the audience perched on the edges of their seats, praying for Heston and Leigh to get out of the way. Just when the tension becomes unbearable, the car pulls away; as the newlyweds kiss, a huge explosion rips across the frame. For Lathrop, the sequence was a great lesson in the art of building anticipation. "It would be a simple scene today," Lathrop says, "but it took all night to light and make that shot. Orson did things on that picture no one had ever done before. I handheld the camera half the time, even on a crane, because Orson wanted visual tension and a documentary look. We used an 18mm lens a lot. I don't even know where he got it. We had it on a Mitchell BNC camera. Of course, you couldn't use the viewfinder with it because you couldn't focus it right. Half the time I was shooting blind."

When Welles was in a scene, and called for a close-up of himself, the only way Lathrop could make the shot was to practically sit in the man's lap with an 18mm lens on a handheld camera. After Touch of Evil, Lathrop felt he was ready for anything.

His first job as a director of photography couldn't have been easier. In 1958, Lathrop shot a series of approximately 50 10-minute films at Walter Lantz's animation studio. The resulting mini-documentaries were used as fillers on television.

Lathrop also filmed his first feature, The Perfect Furlough (aka Strictly for Pleasure), in 1958. The picture was part of a series of low-budget (around $150,000) CinemaScope films Universal Studios turned out with contract players, writers and directors. Directed by Blake Edwards and featuring Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh, the film was shot in widescreen format and color to lure audiences away from their black-and-white television sets and back to theaters.

"I had to put together a crew, but it was no problem because I knew everyone at the studio," Lathrop recalls. "I made a grip into the key grip, and a second electrician into a gaffer. I shot with a 25-speed Eastman color negative film. We needed 800 to 1000 footcandles of key light to get proper exposure. I had to hang 10Ks everywhere."

Lathrop had a 28-day shooting schedule. He got the attention of management, partly by finishing one day early. His second film was a western called The Saga of Hemp Brown, directed by Richard Carlson, a contract actor at the studio. After that film, Universal signed Lathrop to a seven-year contract. He shot four additional films in 1958, and four the following year. The longest shooting schedule was 60 days.

Before the end of 1959, Lathrop started shooting the private eye series Peter Gunn with Blake Edwards, a show that helped change both the look and sound of television. Edwards wanted production values augmented by a distinctive score by Henry Mancini. It was Lathrop's first experience with a Panavision camera and reflex lens, and was also his first black-and-white project as a director of photography.

"Shooting black-and-white is a lot harder than shooting color," he says. "You have to know what you're doing to separate foregrounds and backgrounds, whites and shadows. You have to use light to create a feeling of depth."

Lathrop also shot the 36-episode first season of Mr. Lucky, another detective show directed by Edwards with music by Mancini. He left that show to shoot Hong Kong, one of the first hour-long TV drama series. "We built a tremendous set," he says. "It looked just like Hong Kong. There were a million fights."

In 1961, he got a call from a friend who was a production manager at Universal Studios. He was preparing a picture called Lonely Are the Brave, a black-and-white feature directed by David Miller. It was one of the first films shot in the 2.35:1 widescreen aspect ratio using Panavision anamorphic lenses invented by Robert Gottshalk.

Lathrop also shot Experiment in Terror in 1961, followed by Days of Wine and Roses and The Pink Panther during the two subsequent years. All three films were directed by Edwards.

It's not easy for Lathrop to choose favorite films from his own body of work, but he has particularly fond memories of shooting Point Blank with John Boorman in 1967. "It had an entirely different look," he says. "He made a color chart for every scene. They were never garish. In one scene the colors were desaturated. There was no color anywhere. It was like black-and-white film. There was a very warm sequence and another which made strong use of green."

That same year, Lathrop shot Finian's Rainbow. It was only the second feature directed by Francis Coppola; his first, You're a Big Boy Now, was a comparatively small film. "He had never used a crane before," Lathrop recalls, "but he was very well prepared. He knew exactly what he wanted to do. But it would probably have been a totally different experience working with him later in his career."

Another favorite was They Shoot Horses Don't They?, directed by Sidney Pollack. "It was a very realistic film even though we shot it entirely on sound stages," Lathrop says. "He always knew exactly what we could do. But he would never tell you what to do. He always asked if we could do it. There was one scene where we built a special dolly that the operator could stand on while he was being pushed around a track. It must have been going 40 miles an hour."

Lathrop also liked Earthquake, directed by Mark Robson. "Mark had great rapport with cameramen," he says. "There was always a sparkle in his eyes when he was telling you about his ideas. You could tell how much he appreciated everything you did. He was able to get everyone around him excited about the film."

He started Cincinnati Kid in 1964, with Sam Peckinpah. It was originally supposed to be shot in black-and-white. "We did tests, and were about a week into production when the producers decided they wanted another director," Lathrop says. "They hired Norman Jewison. It was his first big film. There was a rewrite which took three to four weeks. I started to think that it would be a good time to switch the film to color — but a different type of color."

Lathrop came up with the idea of using very soft earth tones— nothing bright. The story took place in New Orleans, in earthy settings, alleys, and cardrooms. He discussed it with Jewison, who loved the idea. "What can we lose?" said Jewison. "They'll never fire two directors."

Lathrop used smoke for diffusion, a technique much in vogue during the 1980s but novel in the ’60s. He also had Harrison create a new set of low-contrast filters which are still in use today. "I used a very light, low-contrast filter," he says. "Everyone thought I was doing it all with smoke, but it was a combination of smoke, filtration, and muting the colors to the point where they almost blended."

Ten years later, Lathrop shot The Killer Elite with Peckinpah. "Sometimes he would do a long, complex shot in one take," he says. "Other times he would come up on the crane with me. He said he liked it up there. We'd wait. He'd do another rehearsal. Finally, I'd tell him, 'We're losing our light.' I'd reload the camera with Tri-X film, and we would shoot in the last light of day."

During the 1980s, Lathrop's feature work ranged from the extremes of National Lampoon's Class Reunion to Wes Craven's Deadly Friend. But mainly he concentrated on TV mini-series and movies of the week. "You work just as hard shooting TV movies," he says. "I shoot them like features. I think of them as 100-page movies. The main difference is that you don't work as long. That way, I can keep my hand in without spending 60 to 70 days on a film."

His most recent Emmy nomination was for Little Girl Lost, which he shot on location in Dallas in 1987. "We shot 10 days out of 20 in what was an abandoned house. We repainted it and added a window and a door here and there, which gave us a source for light."

The picture took place over a two-year period, covering all four seasons. It was shot in November and December. "You just have to pay attention," Lathrop says of films involving different seasons. "You don't shoot trees without leaves if it's a scene that is supposed to take place during the spring or summer."

He created a sense of the passage of time and changes of season by altering the quality of light. In TV, he pointed out, much of this effect can be achieved during telecine transfer.

Little Girl Lost was directed by Sharon Miller, whom Lathrop had met once before; she visited a Kansas location where he was filming a skydiving scene for The Gypsy Moths with John Frankenheimer in 1968. "I didn't remember meeting her, but she told me I was very nice and answered all of her questions," Lathrop says, adding archly, "I'm glad I did because she's become a talented director."

Lathrop believes that many of today's directors are more visually literate. They know what look they want and they know how to get it, so there's more of a dialogue with the cinematographer. But even with faster films and lenses, the basic grammar of cinematography is generally the same as it was when Lathrop started his career as an assistant for Joe Valentine.

Little Girl Lost was about a foster family's attempts to regain custody of a young girl who is living with another couple. They finally find her at a school; in the key shot, the family members are standing half a block away, looking at her. Lathrop shot the entire sequence with long — 300 to 600mm — lenses which distanced the audience from the scene. "I wanted the audience to feel what it was like to be in that couple's shoes," he says.

Today's 500-speed Eastman film is 4 1/2 stops faster than the 25-speed color negative film he used to shoot The Perfect Furlough just about 34 years ago. "I shot most of Little Girl Lost at stop T4 because I wanted realistic depth of field," he says. "That only required around 25 footcandles of keylight."

That meant he could use fewer and smaller units. "I've always used as few lights as possible," Lathrop says, "Every time you add a light, you add shadows. Fewer lights means there are less shadows and a more natural look."

One night exterior scene in Little Girl Lost took place on a narrow road that was fenced on both sides. There was also a swamp on one side of the road. In the scene, a truck drives up behind the girl as she is walking down the road. "Normally, I'd do some cross-lighting, but there was no place to put it," Lathrop says. "I set a high arc about 150 yards away from the action. It was looking right down the road like moonlight. We were doing a dolly shot in the direction of the arc. The closer the camera got to the arc light, the higher the intensity of light got."

Lathrop simply calculated how much he had to alter the shutter as the camera got closer to the arc light. He marked the ground to indicate exactly where each adjustment in the shutter should be made.

"We shot this scene with about six to eight footcandles of keylight," he says. "It was the first time I shot a scene with that little key. If you are around long enough and shoot enough pictures, you eventually get to do everything."

When asked whether cinematography is an art or a craft, Lathrop replied, "It's a craft first; it's something you learn. The art comes from the script, the locations and the lighting. Its all lighting. You want to get as close to reality as possible."

Receiving the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award from his peers was a gratifying experience for Lathrop, but he admits that he was initially a bit reluctant to accept such recognition at this stage of his career. Despite his impressive credentials, Phil Lathrop is still not convinced that he has done it all.

Born in 1912, the cinematographer passed away in 1995 at the age of 82, with Little Girl Lost becoming his final credit.