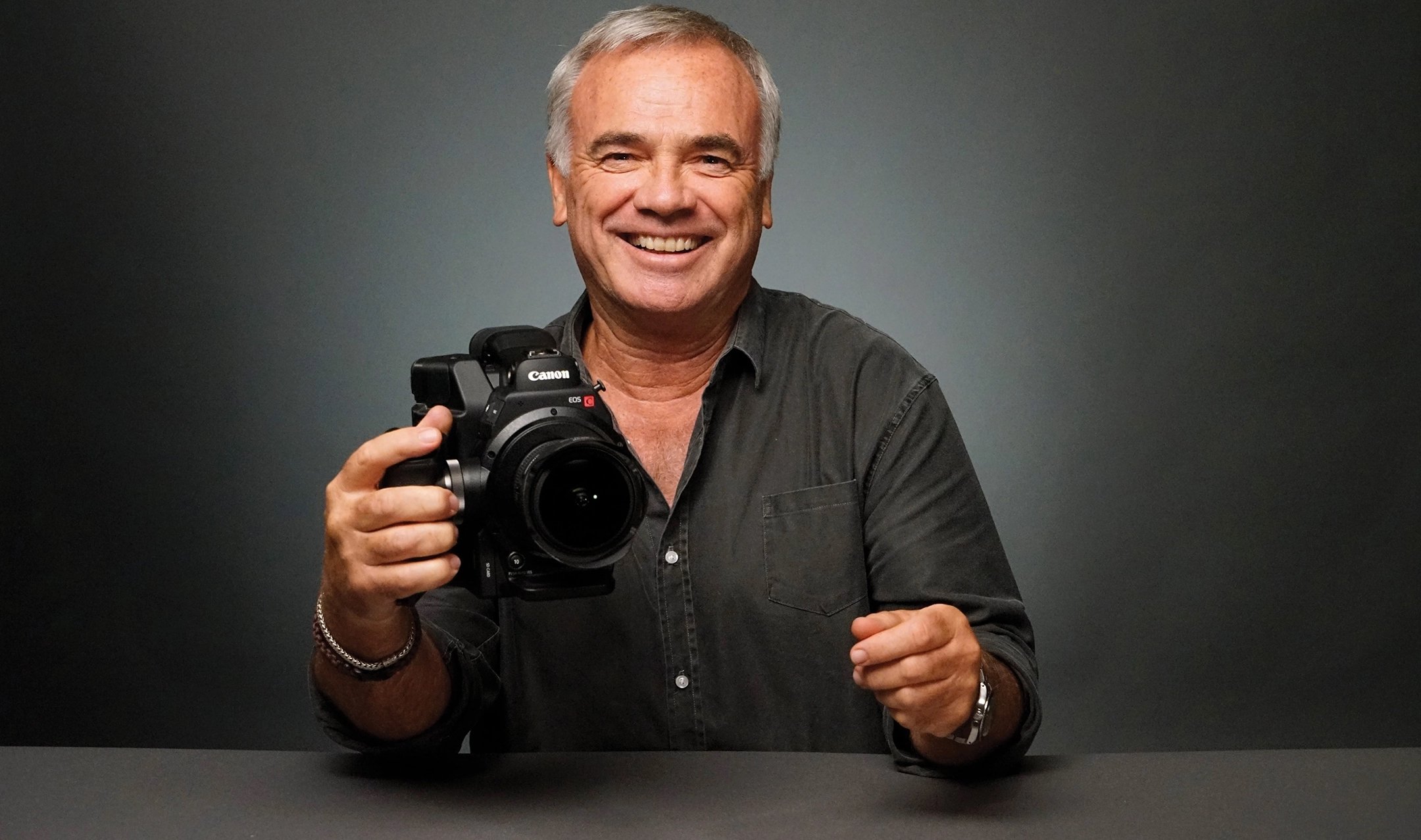

Sam Nicholson, ASC: Uncharted Territory

The visionary visual-effects innovator and entrepreneur is honored with the Curtis Clark ASC Technical Achievement Award.

Creating special visual effects — seemingly impossible motion-picture images essential to telling the story at hand — is an art form that combines daring creativity and trailblazing technology, and requires practitioners who constantly seek new challenges. For Sam Nicholson, ASC, recipient of the 2023 Curtis Clark ASC Technical Achievement Award, this role seems tailor-made.

Nicholson’s creative aspirations sprang from an unlikely background in Monterey, Calif., where his father served with the U.S. Navy Office of Naval Research. “My father was a ship designer and deep-submergence expert,” he says. “He designed the first hydrofoils and was at the leading edge of technology in flying boats. We knew astronauts and aquanauts — all real achievers.”

A youthful interest in scuba diving led Nicholson to memorable encounters with oceanographer Andreas Rechnitzer (who oversaw the 1960 deployment of the Navy’s bathyscaphe Trieste as the first manned descent on Challenger Deep) and Buzz Aldrin (Apollo 11 lunar module pilot and an honorary ASC member). “Andy had been to the deepest part of the Mariana Trench, and Buzz had walked on the moon. As a kid, I thought, ‘How am I going to do something that significant with my life?’ To go to those places, I decided, you have to go to the uncharted territories.

Art, Engineering and Star Trek

Nicholson’s father encouraged him to pursue his ambitions as a fineart painter, with a backup plan to study engineering. This led to UCLA, where Nicholson gravitated to glassblowing, which set in motion his introduction to optics and, eventually, the film industry. “I’d been blowing glass for about four years, and I started looking at light and doing kinetic light sculpture as part of a UCLA master’s program,” he says. “I was projecting light through glass, making glass objects that I felt would create beautiful patterns, and capturing it on film.”

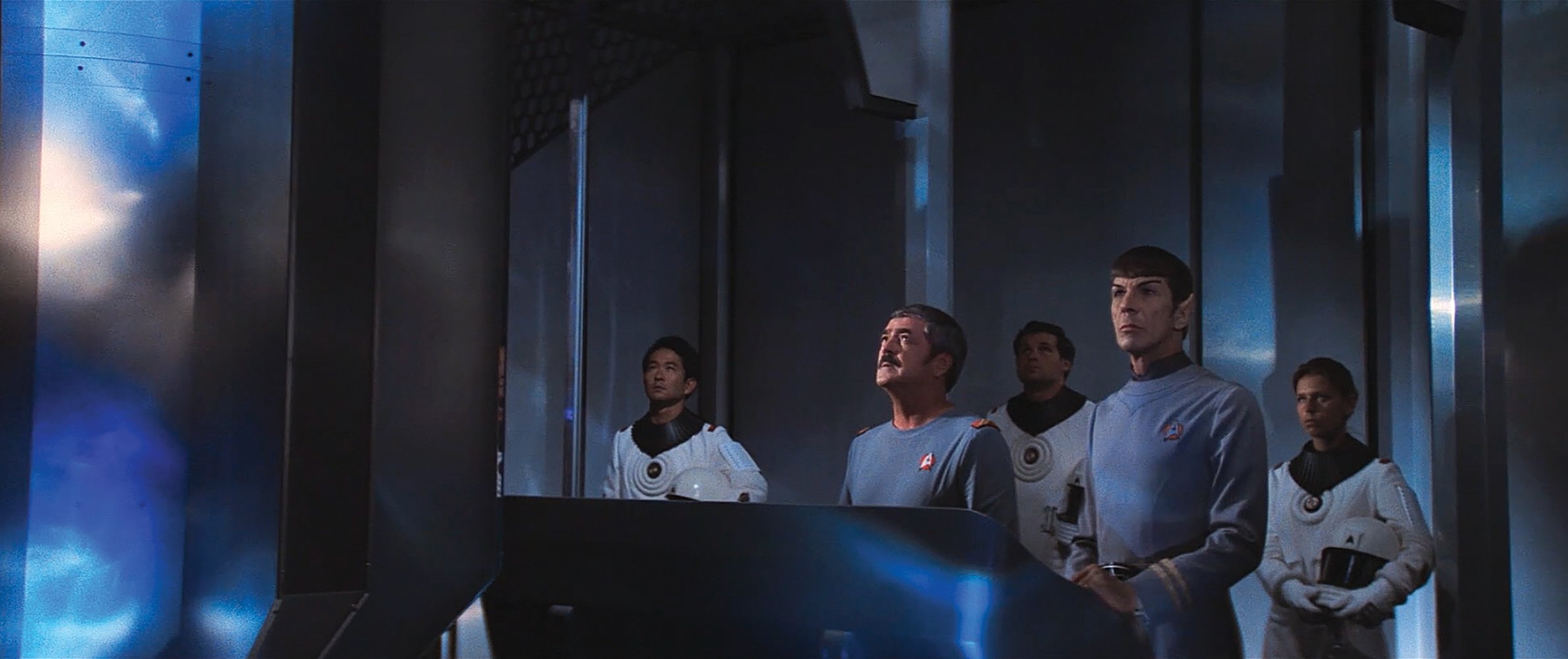

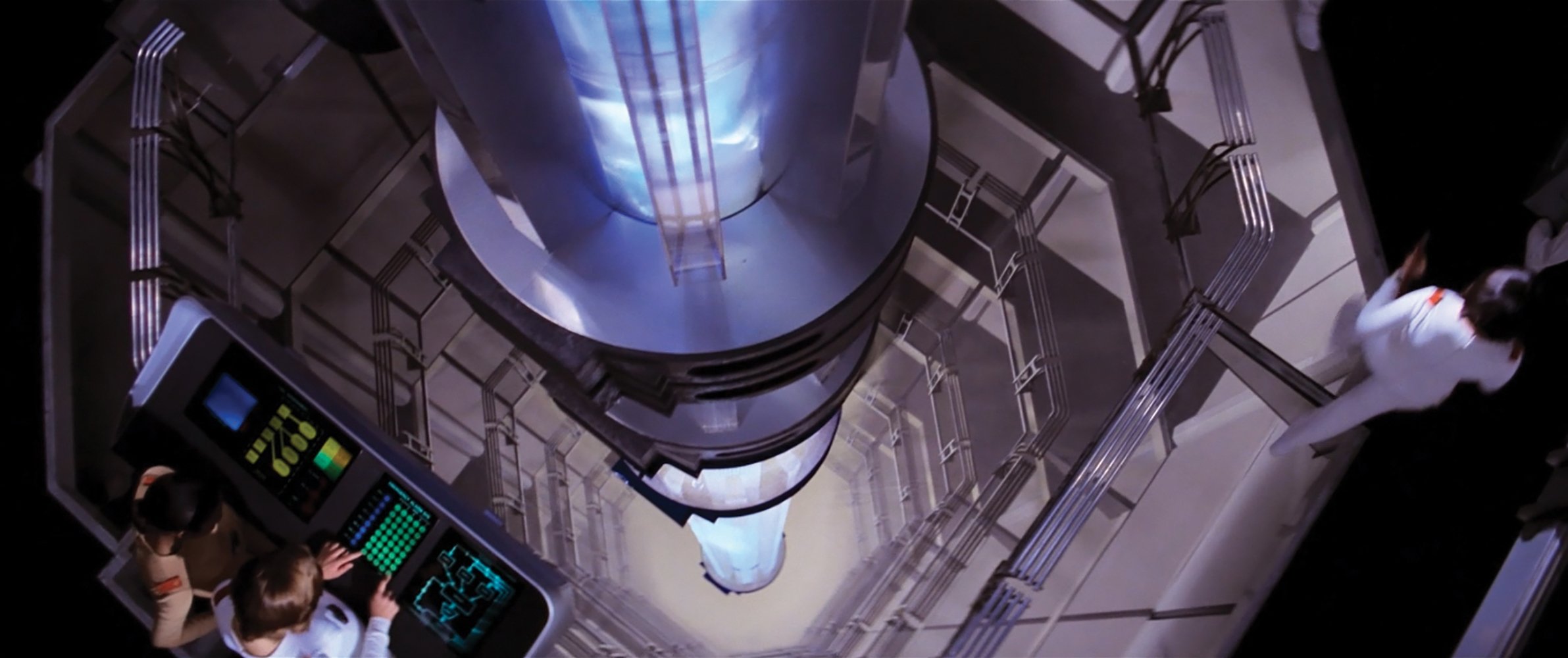

UCLA faculty, including experimental filmmaker John Whitney Sr. and designer John Neuhart, took note of Nicholson’s experiments and referred him to a new project: the sci-fi feature Star Trek: The Motion Picture (AC Feb. ’80). The picture was in production at Paramount, and a unique lighting effect was needed for scenes set in the warp-drive engine room of the Enterprise. Nicholson recalls, “I met with associate producer Jon Povill and director Bob Wise, who was a beautiful white-haired gentleman. They looked at my work and said, ‘Looks good. Can you do it big?’ I had no idea, but I said, ‘Oh, yes, sure.’ So, they gave me a few thousand dollars and said, ‘Come back in a week.’”

After creating a small model to demonstrate his kinetic-light-projection technique, Nicholson met with Wise, Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry, and actors Leonard Nimoy and William Shatner on a Paramount soundstage. Unfortunately, studio work lights swamped Nicholson’s illuminated mock-up, so he begged Povill for a second chance and threw all his resources into building an 8'-tall section of the Enterprise warp core using blown glass that was backlit to create a column of shimmering blue-white illumination. Nicholson won the contract and began six months of work with production designer Harold Michelson and the set-dressing team.

“Our first production scene had [William] Shatner coming down the three-story-high set on an elevator. Bob Wise and I were sitting there, everybody was at attention, and Shatner gave the order: ‘Scotty, light it up!’”

His first day of shooting was memorable. “Under highly secretive conditions at my home in Venice, I’d built a 60-foot-high column of light, which contained 40 or 50 light guns,” he says. “I never turned it on because I didn’t have enough power at my home. At the studio, while installing it into the engine room set, I’d turned it on for 10 seconds at a time as a test. Our first production scene had Shatner coming down the three-story-high set on an elevator. Bob Wise and I were sitting there, everybody was at attention, and Shatner gave the order: ‘Scotty, light it up!’ Bob gave me the thumbs-up, I turned it on ‘high,’ and it was amazing — this white-hot, 60-foot-high column of light. But what I didn’t understand was electronics. I’d put a 10-amp Variac on 250 amps of power, so within about 20 seconds of the first take, my control panel lit on fire. Everybody had heard this was a ‘matter-antimatter reactor,’ and I think they thought it was going to blow up. Someone yelled, ‘Save the director!’ They picked up Bob Wise in his director’s chair, ran out of the stage with him, and everybody ran for their lives. Director of photography Richard Kline [ASC] was up on a Chapman crane, and they were trying to get him out as the ‘reactor’ went into overdrive.”

Following this panic, mechanical special-effects supervisor Martin Bresin came to Nicholson’s rescue by installing a sturdier transformer, enabling production to resume with minimal delay.

Nicholson’s ingenuity earned him Kline’s friendship, and decades later, Kline joined ASC members Francis Kenny, Richard Crudo and Victor J. Kemper in sponsoring Nicholson for Society membership.

Special Lighting Effects

Nicholson’s work on Star Trek established him as a purveyor of special lighting effects, and he began servicing features, television and commercials, first as Spectrum Productions, then as Xenon Productions. In 1989, he founded Stargate Studios, which has grown into a fully integrated visual effects and virtual-production facility in South Pasadena, with satellites around the world.

With Stargate, Nicholson won a Primetime Emmy for the “Battleground” episode of Nightmares & Dreamscapes: From the Stories of Stephen King and received additional Emmy nominations for episodes of The Walking Dead, Grey’s Anatomy and Pan Am, among other projects. Recently, he served as a virtual production supervisor on such series as Our Flag Means Death and Your Honor, as well as Noah Baumbach’s feature White Noise. Stargate’s virtual-reality expertise has led Nicholson to become an IATSE spokesperson for hybrid cinema tools, exploring new paradigms for on-set imaging.

Max Headroom

Nicholson’s career has encompassed directing commercials for J. Walter Thompson; designing kinetic-lighting effects for music videos for Whitesnake, Aerosmith, Scorpions and Cher; and feature-film work that include Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (AC Oct. ’82) and Ghostbusters II.

A friendship with cinematographer and visual-effects supervisor Peter Anderson, ASC led Nicholson to establish a studio on Hollywood Boulevard, where Xenon Productions constructed a futuristic miniature cityscape that incorporated repurposed motion-control equipment for the ABC television series Max Headroom. “It was a 70-foot miniature with 20 miles of fiber optics laced through hundreds of miniature buildings. We built a motion-control gantry to fly a camera through, and each week we designed different shots. We left it up for the entire series, and every day’s dailies had to be in-camera perfect, with multi-pass motion-control on film. All of a sudden, I became ‘the miniatures guy.

“Hollywood is funny because if you have one success, you get known for that very quickly. I look at the production business as the most collaborative and educational art in the world, but it’s like going down the rapids on a very large river in a kayak — you don’t know which way the current is going to take you. So, you take risks and find solutions.”

Full Circle

As the visual-effects designer on Highlander II: The Quickening, shot by Phil Méheux, BSC, Nicholson created innovative “quickening” energy effects by manipulating laser light. “We built three white, multi-spectrum lasers into a multi-plane animation stand. We fed the lasers via fiber optics through an acousto-optic modulator, which created 16 million colors. We used galvanometers on mirrors to manipulate the light and used a stylus to draw on a tablet, and the light followed your hand, animating laser light directly onto film. An old Mitchell camera on the down-shooter photographed the raw light hitting a rear-projection screen. It was an enormous undertaking. We used that laser-animation stand extensively, including for title design. Strangely, we’ve now come full circle to where virtual production has become all about what you can pull off For scenes in Star Trek: The Motion Picture depicting the warp-drive engine room of the Enterprise, Nicholson built a 60'-tall set piece using blown glass that was backlit to create a column of shimmering blue-white illumination in-camera, which is where I started.”

Nicholson’s journey to the virtual realm was built on a career’s worth of creative partnerships. A prime example was when Star Trek: The Motion Picture visual-effects designer Douglas Trumbull invited Nicholson’s collaboration in the 1990s to film elements and write computer code for interactive CD-ROM games. Stargate’s television work introduced Nicholson to Volker Bahnemann — former CEO and president of Arri’s U.S. divisions, who invited Stargate’s participation in emerging digital camera technologies — and to associations with Sony and Canon.

“It’s critical for anyone trying to predict the future of any process, like cinema, to understand the technology from an engineering standpoint,” Nicholson says. “This goes back to my father, who insisted I study engineering as well as art; those disciplines are at the core of cinematography. It is the responsibility of the cinematographer, visual-effects supervisor or virtual production supervisor to find the right blend of art and technology. Once you’re comfortable with that, you can throw away the sheet music. And that’s when your work starts getting good.”

Virtual Production

An early breakthrough in virtual production came with Nicholson’s work on Star Wars: Underworld, a proof-of-concept test for Lucasfilm that was shot on a partial greenscreen stage with live digital-environment playback. That led to Stargate’s suite of virtual-cinema tools, which integrate visual-effects design with an on-set camera and lighting interactions. “These are all hybrid technologies,” says Nicholson. “They combine all the experience that you have on set into lighting technology and code. My perspective on the industry is unique because I got into production from the point of view of, ‘What can you achieve in real time on set?’ Virtual production is like a theatrical performance. We now have an incredibly complex set of tools such as Unreal Engine and DaVinci Resolve, and powerful technologies that you can bring to set, like LED screens, spatial tracking and kinetic lighting. The challenge is to seamlessly integrate these technologies and do it in real-time.

Nicholson manages virtual and in-camera elements using Stargate’s ThruView system. “It uses custom code that combines kinetic lighting, tracking and image control on multiple screens. The reason we call it ‘ThruView’ is that it turns LED walls into ‘panes of glass’ that feel as if you are looking through them rather than directly at them. When we move a ThruView-enabled LED screen, the image changes on the screen to match the appropriate camera angle. It’s like building a giant, three-dimensional, multiplane animation stand on set, moving image planes around inside a volumetric, image-making machine.”

What’s Next

Stargate’s educational outreach has included teaching virtual production for the ASC Master Class program — and to members of IATSE Local 695, which includes production sound, video engineers, video assist and projection engineers. “The unions are working to integrate new technologies such as LED playback and volumetric lighting,” Nicholson says.

“There are brilliant artists in the ASC that I’ve always looked up to, and, in turn, I’ve had the privilege of influencing many young people. That’s why I believe education is so important.”

“I’ve been collaborating with Kino Flo on a new light based on kinetic lights we built at Stargate,” he adds. “Pixel-track lights have an image on them, and they respond to the image. It’s a light, but it’s pixel-addressable, and it’s tracked to the original image — when an object goes into a tunnel, the light goes out; or if it passes by a streetlight, the object acts like a streetlight illuminating the actors. Now, is that a light, is it playback, or is it a visual effect? It’s a lot of things!”

Nicholson sees the future of virtual imaging in the work David Stump, ASC conducted with Lytro Cinema’s light-field image capture, which enables calculations of depth and focus in 3D space. “Everything coming out of cameras today is flat imaging,” says Nicholson. “With imaging arrays and artificial intelligence, we’ll be able to calculate true depth and depth mattes. At that point, bluescreen might become obsolete.”

Though Stargate’s accomplishments have led to collaborations around the world — and a forthcoming studio in Mexico City — Nicholson says he was surprised and “humbled” to learn he would receive the Curtis Clark Award. “There are brilliant artists in the ASC that I’ve always looked up to, and, in turn, I’ve had the privilege of influencing many young people. That’s why I believe education is so important. What better thing can you do than light creative fires in people? It’s the people you meet and the opportunities for new artistic collaborations that excite me. I can’t wait to see what’s next. And I’m so grateful to the ASC for this tremendous honor.”

You can watch the entire ASC Awards ceremony (including Nicholson's tribute reel and acceptance speech) here.