Vengeance Most Fowl Mines Classic Visual Cues

Dave Alex Riddett, BSC on illuminating this humorous Wallace & Gromit animated tale that pokes fun at genre lighting tropes.

All images courtesy of Netflix.

Stop-motion animation was for decades the only way to get non-human-shaped monsters and creatures on movie screens, from Willis O’Brien’s 1925 The Lost World and King Kong to the menagerie of mythological beings and dinosaurs brought to life by Ray Harryhausen from the 1950s to his last film, 1981’s Clash of the Titans. Computer-generated effects supplanted stop-motion for monster effects after 1993’s Jurassic Park, but a parallel province of stop-motion has survived and thrived even in this computer-dominated cinematic era. More comedic, stylized stop-motion has been popular at least since George Pal’s Puppetoon features up through the adventures of Gumby and Davey and Goliath in the 1960s and more recent features including Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas and Frankenweenie, Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr. Fox, Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio and Travis Knight’s Kubo and the Two Strings.

“We always used to say we treat a story exactly the same as we would in a live-action movie.”

— Dave Alex Riddett, BSC

The award for dogged creativity and longevity, however, has to go to Aardman Animation and their ongoing Wallace & Gromit series, about an absent-minded inventor (Wallace) and his loyal but put-upon canine companion Gromit. Beginning with 1989’s A Grand Day Out, Aardman’s features and spin-offs like Shawn the Sheep have entertained audiences in theaters and television and won both an Academy Award for Best Animated Feature and a BAFTA for Best Film for 2005’s Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit (see AC Oct. 2003). Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl is Aardman’s latest project, directed by Merlin Crossingham and Nick Park from a script by Park and Mark Burton. The story started as the tale of Wallace’s invention of Norbot, an overly helpful robotic garden gnome — but Burton and Park realized the story needed a villain and found one in the silent but deadly criminal penguin Feathers McGraw from Aardman’s 1993 short The Wrong Trousers, who reprograms Norbot for evil and inadvertently creates a marauding robot gnome army.

To capture these characters on frame by laborious frame, Aardman employs veteran Dave Alex Riddett, BSC, who began working with Aardman founders Peter Lord and David Sproxton around 1984 and soon joined Aardman in working on Peter Gabriel’s legendary “Sledgehammer” video, which saw the Aardman team animating Gabriel himself through a process called pixelation. Riddett did stop-motion animation while he was attending art school. “Animation was always an easy way into making movies, which is what I wanted to do, basically,” he says today. “I was brought up in a little village, but in the town cinema they quite often had things like the Sinbad films. I got into Ray Harryhausen very early on, so I was well aware of that mix of animation and live action. I mean, Ray is obviously a big influence on a lot of us.”

FEATHERS McGRAW

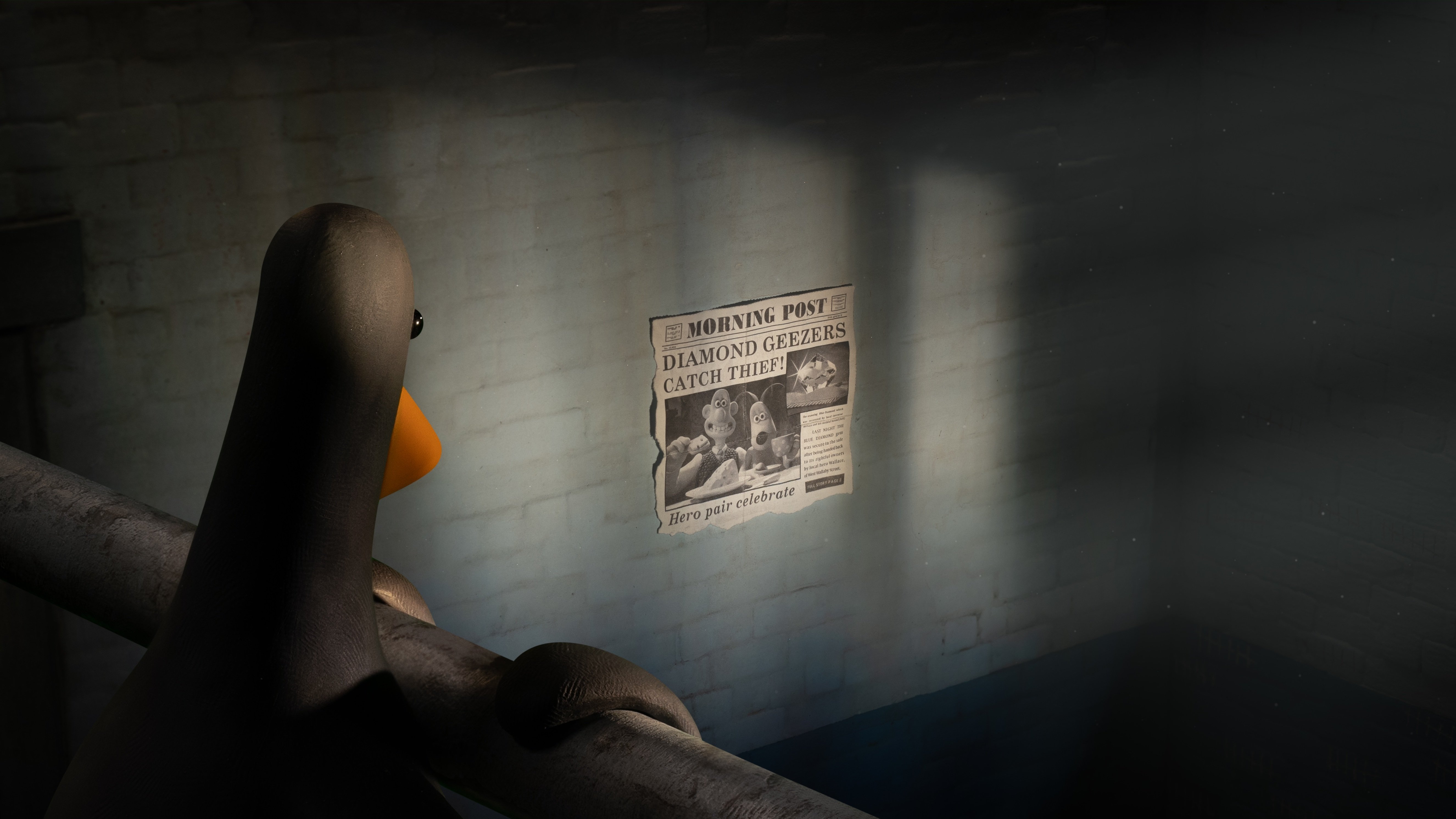

Of course, Ray Harryhausen was not noted for his comedy. Riddett has mastered the art of contributing to Aardman’s very specific, droll sense of humor with his photography. That becomes especially important in the lighting and framing of Feathers McGraw, a silent and almost completely inexpressive character with a head like a pencil point. McGraw is introduced working out in prison in a takeoff on the gripping crime drama Cape Fear, shot by Freddie Francis, BSC (see AC Oct. 1991), and Riddett used some of the visual language of film noir to photograph the character.

“It was a joy to do the Cape Fear thing there, because we get back to the noir sequence, which is quite ridiculous.”

“We create a reality and then put these weird characters into it who seemingly fit because of the way we shot it,” Riddett says. “But Feathers, we light him simply because he’s such a beautiful shape. When he's in the prison cell, I just had a strong blue light on one side, for the cells seen through the window of the prison, and then this flickering candlelight on the other side. I try to keep it that simple, really, because it's the minimum of movement that suggests great evil intent. It's like lighting to illuminate the dark inner soul, as I call it.”

Riddett says that McGraw’s basic design adds comedic impact. “He's a shape, but he has these beady eyes, which are fantastic,” he says. “And you just have to make sure that the key light just catches those eyes. You get that little spark in there. I thought on this film, I've always in the past, going back to The Wrong Trousers, and Wrong Trousers was done very simply — no rigs or anything. There are no special effects in there, and the lighting is pretty damn simple on that. I did think for this film, I might put special key lights in there to hit the eyes. But, generally, I found the way I lit the scene, [McGraw] actually picked up those little light sources — I mean, his little beady eyes, which is how you seem to read what he's thinking.”

McGraw’s introduction a la Cape Fear is deliberately over-the-top, but as we eventually discover, the character is less a notorious criminal in maximum security than an ordinary penguin on display at a local zoo. But Riddett’s noir-style lighting with its stark shadows suggests McGraw’s inner perspective of serving hard time. “When we did the Cape Fear thing, that's what I was striving to achieve with the first sequence where we see him when he steps forward from the bars,” Riddett says. “That was the first time I tried to establish that noir look. We just see him in the shadows with the bars behind him, and then he steps forward into the light. So that's the first time we see him. But then there's a little bit of his interplay with the guards, which shows his true menace. It was a joy to do the Cape Fear thing there, because we get back to the noir sequence, which is quite ridiculous. I mean, a penguin, but again, trying to keep the lighting simple on there, with nice, strong shadows on the wall behind him — evil little devil!”

Riddett used LEDs to create the effect of candlelight in McGraw’s “prison cell” zoo enclosure. “The candlelight was actually three LEDs on little wires, just slightly separated from each other, and they were programmed into the computer again so they would flick from one to the other, which just gave the flickering candlelight,” he explains. “That's a fairly simple device, but they're out of shot, of course. They wanted the candlelight to actually move around slightly, as if it's a flame going backwards and forwards, as well as flickering the shadows. So the shadows are alive as well.”

“The great skill of the animators in keeping that minimal movement is to get that sort of evil intent, or that calculation he thinks going on inside his head with just very small movements.”

A shot of McGraw loitering near what appears to be a prison wall pulls back to reveal a faux Antarctica zoo environment complete with a dome-shaped overhead cage, fake icebergs and a pool being viewed by zoo attendees. “There's a big brick wall behind which is part of the zoo building, which is where his cell is,” Riddett says of the miniature set. “Just to the right, there's a bit of open sky. And I think that's the only thing we put with the greenscreen in there. Most of that was in camera, I think. And again, it was generally quite stark lighting on that one to get because we also had that pull back. The bit of the joke is that, yeah, he's got this evil penguin in there, but when we do the pullback to reveal where he actually is, it's a pretty bright, sunny day, and there's kids playing at the front, and they're not very interested in the contents of this particular case. So he's quite forlorn within that.”

Once McGraw reads of Wallace and Gromit’s responsibility for putting him behind bars in the local paper, he draws his plans against the pair and uses telescoping pliers to hack into the zoo’s security computer and Wallace’s home computer where the coding for Norbot is stored. “The great skill of the animators in keeping that minimal movement is to get that sort of evil intent, or that calculation he thinks going on inside his head with just very small movements,” Riddett says. “But in lighting him, it was keeping it as simple as possible, and I was very pleased with the prison sequence, where he's got his little grabber going through the sort of hole in the wall. It's like that contrast between the slightly dull mixture with the guards sitting there and he's in his mood-lit cell with a candlelight flickering.”

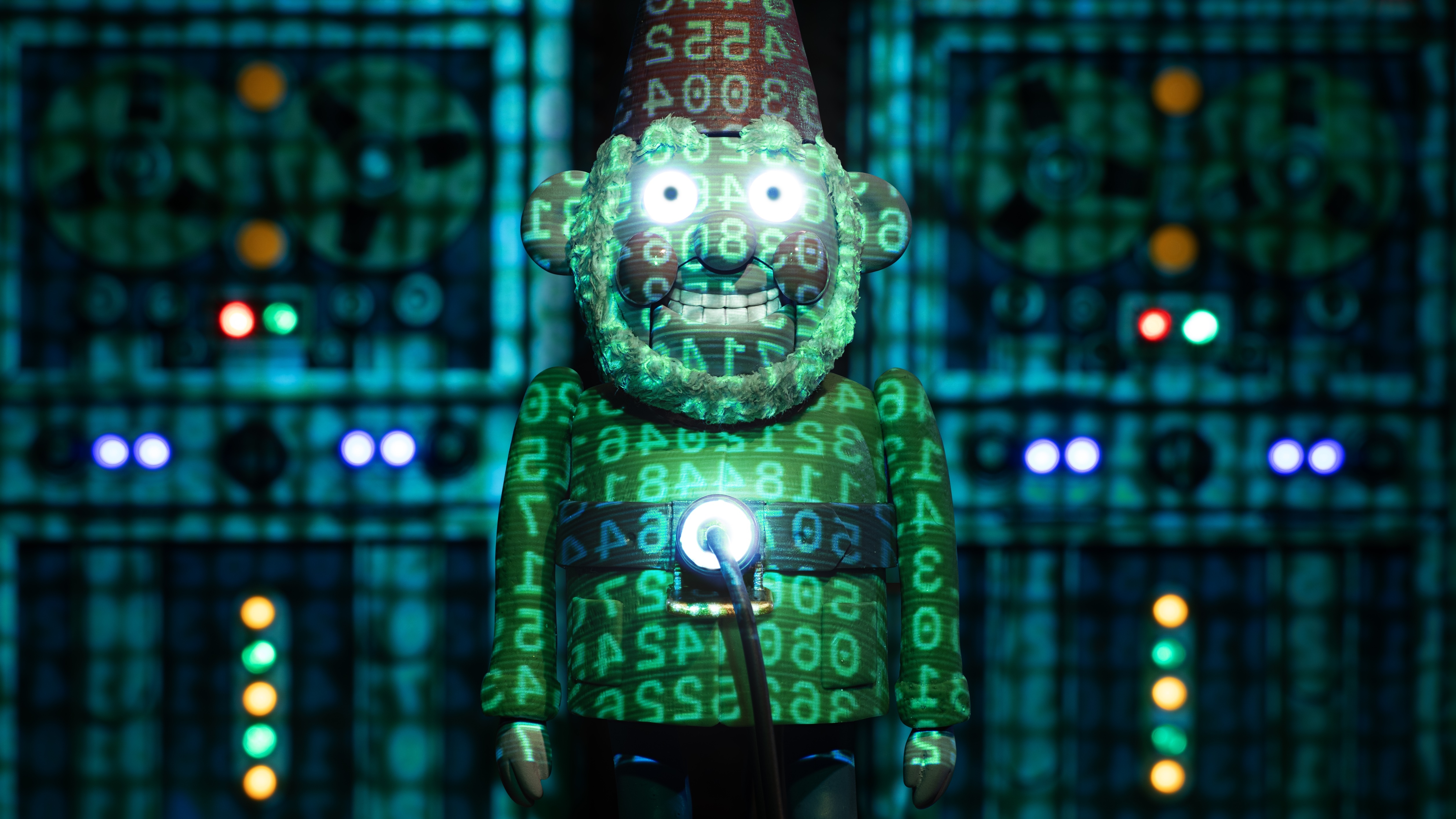

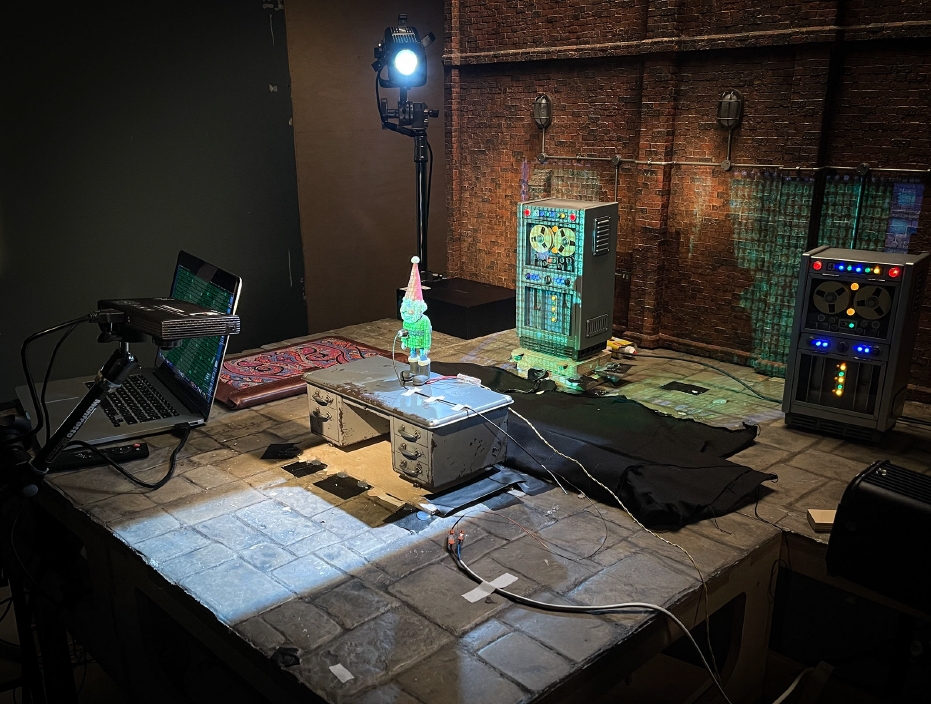

THE MATRIX SHOT

McGraw’s infiltration of Wallace’s computer system results in the malevolent reprogramming of the overzealous Norbot in a sequence that pays homage to the sci-fi action classic The Matrix, shot by cinematographer Bill Pope, with lines of familiar green code superimposed across Norbot’s body. The image is so vivid and immersive it suggests computer-generated effects, but like many of Riddet’s shots for the film, the Matrix homage was achieved entirely in-camera. “I remember when we looked at it in storyboard form, I think the consensus was that this was a VFX shot — this will have to get into effects to achieve this,” Riddett says. “And my thought was, ‘Well, no, it's numbers being projected onto a character, onto a puppet. I'm going to do it that way.’ Rather than get a bulky sort of a video projector, I ordered one of these little miniature ones, and they're remarkably good.”

“I find it so important in this work — one of the joys of it — is that it is real. There’s something real in front of the camera.”

To achieve the right look, Riddett asked an effects supervisor to make him a Matrix-esque set of computer code: “I sent a bit on my laptop and I projected it onto the puppet. And I thought the result, remarkably, was great. Then the advantage of doing it that way is that the animator, when he's animating it, it's all happening around me, it's actually there, and he's controlling it as well. So the laptop had this video on there and the animator could advance it frame by frame himself. And lo and behold, you saw it on the character. Also, you could immediately see what effect the projection had on the background. So there's numbers on the computers behind out of focus, which is almost like water dripping there because it's soft, which is something we wouldn't have anticipated if we'd done it as a post effect. I love doing things in camera, and that's a good example.”

The in-camera effect, to Riddett, is key to the appeal of stop-motion work. “I find it so important in this work — one of the joys of it — is that it is real,” he says. “There's something real in front of the camera. And I think if you've actually got that in front of you while you're animating, I think it helps the animator, inspires them. You certainly feel you're more part of the process — you're in command of the process. So, and I think that's part of the secret, is keeping it as pure as possible, and obviously, later on, we have used a lot of water and fog effects; the visual effects group did a brilliant job. But I say my starting point always was, let's put it in front of the camera as much as we can and shoot it here.”

He adds, “At one point, we got visited by our composer, [Lorne Balfe], who arrived to have a look around, and he saw this thing all set up there. And he says, ‘That's brilliant! I've been working with these effects films, and you never get to see it on the set, but here it is. You walk onto the set and the effects already there.’ He’s been working on top kind of films like that, and he says it's so refreshing to be able to see something actually happening in front of your eyes.”

THE NORBOT GNOME ARMY

The reprogramming of Norbot adds a sinister aspect to a character who heretofore was merely annoying. Riddett augmented Norbot’s creepiness factor by zeroing in on the robotic gnome’s face, which is only an inch or two in diameter. The Aardman team has acclimated themselves to a scale in which their stop-motion puppets are a little larger than a human hand. “The scale is always the same, and that scale was based on what's easy to animate, really,” Riddett says, picking up a puppet of Wallace. “So, while this is about nine inches tall, the animators discover what's easy to manipulate. Anything too big is too unwieldy, anything too small, that could be quite painful to animate.”

Updated lighting technology, including tiny LEDs, has expanded Riddett’s palette for lighting miniscule stop-motion characters. “We use things called micro ellipses, which are little profile lamps, which are about the scale of the characters, really, as opposed to using enormous film lights and their image control,” he says. “They were incandescent until recent years, but now we're swapping everything around to LED sources. But it's the controllability of the lights — they have to be very controllable. Historically, we've always used theater lights like profile lights with shutters and things where you can put gobos inside them, just because they're more suitable and more controllable for what we do, this sort of precision that's required.”

Riddett even recreated the effect of light moving through a stained-glass window to add an unnerving quality to a closeup of the Norbot’s face: “One of my team lit that one, but, basically, the instructions I gave them is that it wants to look slightly macabre, and one thing that helped it for me is that the light is actually coming through a stained-glass window in Wallace’s front door. So that's the light source. That's got this very acid-y yellow light we've mixed with blues. It's quite an unusual light source, and a perfect procedure like that, where you want to make them look very macabre.”

THE HELLSCAPE

Part of the humor of Vengeance Most Fowl comes out of the shift back and forth between the sunlit and jolly atmosphere of Wallace’s house and neighborhood and the movie genre moods Riddett helps recreate, from the film noir look of McGraw’s incarceration at the zoo to ever more horrific atmospheres as Norbot reproduces himself into a Norbot army and turns Wallace’s basement into a red-hued Frankenstein’s laboratory.

The ambitious “hellscape” set features abundant Norbots hammering away on arching scaffolding and catwalks with fireworks-like sparks from welders and other activity, all adding up to one of the most memorable and gothic images from the film. The final set was such an inspiring idea that RIddett didn’t want to farm the look out to his associates. “As the director of photography, I have a big team of people, and then I have to subdivide other sequences to various people to shoot,” he says. “But in the early stages, when I was setting up and working things out, I looked at that, and I thought, ‘Right, I'm definitely keeping that one. That looks very interesting.’”

“The animation software we use is called Dragonframe, and that has the facility of taking the images, and you could actually control lights with it as well.”

Some of the design had been sketched out by a concept artist, but Riddett brought some other ideas to the table. “Something I remember from when I was at art college, and I used to travel up from the Midlands in the U.K. up to the north and Leeds,” he recalls. “I used to pass through a place called Sheffield, and the train would go through the Sheffield steelworks. This is back in the early ’70s, when we had a steel industry. The train would go through what looked like Hades. There was this massive structure with fire spitting out of it, and this is at nighttime, because the things were going constantly. And I remember as a teenager looking at that thinking, ‘Oh, God, I'd love to use that as a film idea, because it's so overpowering.’ And eventually it came around to it, when I saw the drawings there for what they thought this was going to look like, this basically ridiculous scene of industry in this small basement. I remember the steelworks being bright red and the fire and the flickering of lights, so that was a big influence on how I lit it.”

The ”Hellscape” atmosphere involves extensive backlighting, so Riddett worked with the set builders to construct a set with a great deal of transparency to it. “There's a big red light source on the back there, then lots of smaller light sources to give the flickering effect,” Riddett says. “All of it is fed into a computer. The animation software we use is called Dragonframe, and that has the facility of taking the images, and you could actually control lights with it as well. We worked out a lighting pattern, really a flickering lights left, right and center lighting the basement up, which we programmed in there and had it set up in advance and we could repeat it again.”

Riddett says the repeatability is particularly important for the removal of animation rigs used to support characters in mid stride or otherwise suspended in air. “There's camera moves on there as well,” he continues. “The camera moves in on it to start with. So the whole thing was programmed into the computer so that we could repeat it over and over again, just so the animator can be just left to it.”

Riddett even arranged to have the sparkling welding effects added in-camera. “I bought one of these miniature video projectors, and from a previous film, I got some animated graphics I did, especially for firework display,” he explains. “So I incorporated those behind the set itself. It's all back projected — I actually had animated patterns being projected onto the translucent backgrounds. So it was a sheer joy for the lighting to play with that. I think it's roughly about the same time I went to a big music festival, which I've been going to for years. I suddenly realized it was a bit like that as well. It's like one of the big rave stages, all these flashing lights going off. All that stuff is in my head somewhere, and I figured, oh, this is a chance to play with that sort of lighting.”

“What we have in stop-motion is the ability to create a new reality — on that suits those characters, because the puppets are caricatures, they are not human beings.”

THE GREAT INDOORS

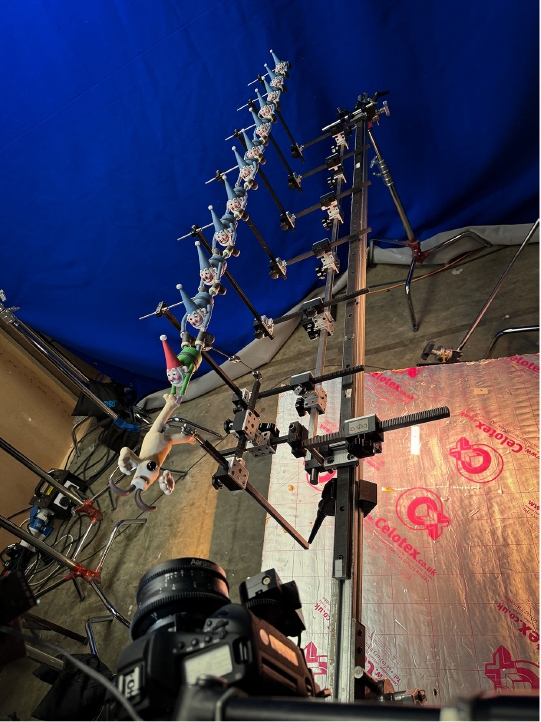

A challenge for table-top animation is reproducing the look of the outdoors while working very much indoors on a soundstage. The exterior scenes for Vengeance Most Fowl open the film up for more expansive action, which often requires elaborate rigs to support characters that must appear to be flying or falling through the air. In addition, miniature exterior sets often boast greenscreen backgrounds so that sky backgrounds can be filled in later.

“One of the first things we built together was a whole row of houses,” Riddett says. So that's very typical, the terrace streets of Northern England as a particular feature. And again, this is reusing a lot of the old sets and the old buildings there, and just building a very long street, putting a big camera track alongside it there. And that became the background for many a scene, whether it's daylight or nighttime.” Aardman keeps a vast reserve of in-scale buildings and other props that can be adapted and reused from feature to feature. “That's quite useful, because you appreciate everything has to be built and in great detail as well,” RIddett explains. “So it's nice to actually have stock items or things we can adapt.”

Riddett says that recreating outdoor lighting conditions on the soundstage is fairly simple, but the complexities of stop-motion do throw him some curves. “One key light will give you the air, the sunlight effect there, or the moon light. And there's various ways you'll filter that. Quite often, for moonlight, I'll bounce the light off a silver board, just so it's not so direct. It gives a bit more of a moonlighting look. But generally, you keep the strong key light and the fill light that generally creates the feeling of bringing out there.”

Riddett is not above using an old-fashioned cucoloris under the key light to break up the light for urban settings. The placement of lights is vital to getting shadows in the right place, but of course the complex mechanical rigs that support the stop-motion characters in some shots are not supposed to cast shadows. “We use a lot of rigs to hold the characters up, so I have to be sort of careful where we keep lights from, because we can't be throwing shadows of the rigs over other animated objects because it's difficult to paint them out,” he explains, noting that in those cases the greenscreen backgrounds help to isolate the characters and make digital tweaking easier. “Sometimes we’ll shoot with the characters actually on rigs just traveling along the road, actually in front of the whole street set,” Riddett explains. “Sometimes, for practicality, we would just fill the background separately, and then the foregrounds we’d be shooting in front of a greenscreen to hit with lighting effects to share the passing of lights and things on the on the car interior.”

An early scene of the Norbots hitting the streets for their first job featured a lot of rigging. “When the gnomes are actually going out to do to their first job, most of that was all in camera again, with some very, very complex rigs coming out of the back of the van for the little guys coming out in the scooters and stuff,” Riddett says. “Again, it's sometimes a lot simpler to shoot with bluescreens and greenscreens and then separately. But again, where possible, you try to do it all in one, slightly more complicated for us and for the animator. But again, I think there's more fun in it that way. And it does dictate the look of it to a certain extent.”

For the climax of the film, a huge valley for a train overpass was created, where Gromit would eventually dangle on a chain of Norbots struggling to prevent him from plummeting to the valley floor and his doom. For sequences like this the 9” scale of the “hero” puppets had to be abandoned. “For certain things like the chase sequence, when in the valley, we had to build a miniature valley, a much smaller scale one,” Riddett says. “We did also build a half-scale train for the scene at the end, because it was difficult to get that sort of detail into anything really small, and anything [in the main puppet scale] would have been too big to build. But generally, we've stuck to that main scale.”

Anyone who’s watched an old Ray Harryhausen film knows that there’s often little if any camera movement during the stop-motion scenes, especially if Harryhausen’s creatures are interacting with live action people. Tabletop animation, where live action elements are not involved, allows for some movement but executing camera moves frame-by-frame is still a laborious process — but motion control and other technologies have made it easier, and Revenge Most Fowl is filled with dynamic camera moves. “We always strive to do it,” Riddett says of the moving camera. “And, obviously, in the early days, certainly Wrong Trousers and A Close Shave, there wasn't really the technology — we didn't have computer-assisted motion-control frames. But we always wanted to have good movement, and Nick is very keen on that. A lot of our films are homages to things we've seen and grew up with, and a lot of those films that we like, the movement is part of the storytelling, so even back in Wrong Trousers we had home-built trackers so we could track, we could tilt the camera around geared heads, and you just put markings on the side.”

Riddett says that most of the camera movements are carefully storyboarded but he and his team collaborate with the directors to finalize them. “The storyboards are quite animated,” he points out. “I mean, they are drawings. But I'm also in at the edit stage. They will mock-up the move the directors are after, and we'll probably refine them on the floor. And of course, the directors are there day by day with us when we're setting things up. So we can quite quickly give them stuff to look at and they can make comments about it. So they are very carefully designed.”

One of the trademarks of stop-motion has always been a certain herky-jerky quality that gave away the game for monster movies because the movement didn’t match the mass and shifting of flesh seen on a real creature. But that same quality adds a dynamism and unpredictability to full stop-motion projects, and Riddett says that CGI’s capacity to smooth out motion and eliminate errors would rob Aardman films of their character. “Certainly, I think it's a shame to smooth out some of the idiosyncrasies of stop-frame, because you also find the problems, and there's a lot of problems filming stop-frame — but I think those problems actually dictate the look to a certain extent, and the esthetic of it,” he says. “I think it's important to embrace those problems, and embrace the fact that it is real, because the audience knows that. I mean, to try and smooth everything out, to smooth the goodness out of it, I think is a shame, because it has a particular look, and I think people relate to it. They know it's for real. They know they could come along and put their hand inside the set.”

Ultimately, it’s the mix of hard-edged reality and cartoon excess that distinguishes Aardman films like the Wallace and Gromit features from CG-animation movies. “We always used to say we treat a story exactly the same as we would in a live-action movie,” Riddett says. “But, of course, what we have in stop-motion is the ability to create a new reality — on that suits those characters, because the puppets are caricatures, they are not human beings. The proportions aren't the same. So you have to appreciate that. The style is to create a reality that everybody's drawn into and convinced by, and the advantages of that is we can take it any way we like.”

That includes the shifts in cinematic style that make Vengeance Most Fowl so entertaining. “We go from these domestic interiors, which are nice and cozy, and we can suddenly segue quickly into something quite macabre, like a Hammer horror film or a Hitchcock film,” Riddett adds. “But you have to be careful how you allow for that sort of transposition. But once you've created that world and you stick to it, the world is your oyster. Then we can take it into all directions, and that desire to play with light and shape and camera moves helps tell the story.”