A Hostile Takeover in War of the Worlds

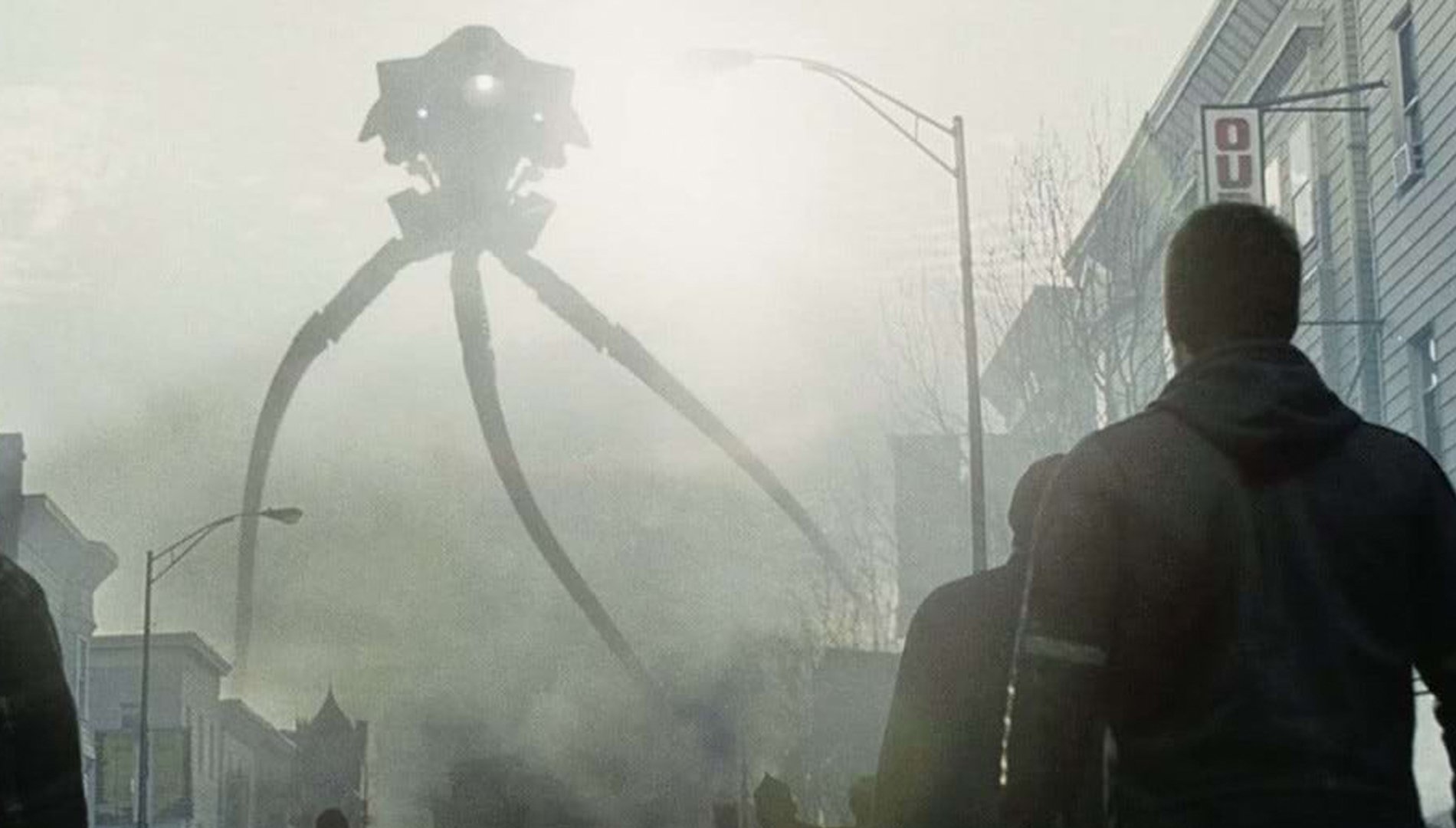

Humans combat an alien invasion in War of the Worlds, shot by Janusz Kaminski.

This in-depth look at the making of War of the Worlds first appeared in American Cinematographer's July 2005 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

Steven Spielberg’s films have often portrayed extraterrestrial life in an optimistic, positive way, but his new film War of the Worlds, based on H.G. Wells’ sci-fi chiller about an alien invasion, takes a distinctly darker view. As director of photography Janusz Kaminski, ASC attests, Spielberg wanted to amplify the horror of the story by grounding the film in the perspective of its flawed, very human central characters. “Steven puts human emotions into this film — a story that people can follow with characters we can relate to,” says Kaminski, whose work on the picture marks his ninth collaboration with Spielberg. “This isn’t a film where things are just blowing up and there’s no sense to it. Things happen for a reason, and they’re motivated by what the characters are experiencing.”

Spielberg explained this idea further during a press day while the production was shooting on location in Piru, California. “On Saving Private Ryan [see AC Aug. ’98], I wanted to get deeper into what combat was really like from the soldier’s perspective, based on all of the things I’d heard and read about from veterans of World War II. I wanted to put the audience into that mindset. For this film, I wondered whether I could bring some of the tools we used on Private Ryan to tell a realistic story about an intergalactic invasion of the planet Earth.”

At the core of this idea was updating Wells’ setting from Victorian England to modern-day America, and populating the film with realistic characters. “The point of view is very personal,” says Spielberg. “People will be able to identify with the characters in the film because it’s about a family trying to survive and stay together while they’re surrounded by the most horrible events you can possibly imagine. Also, the film doesn’t have the stylization of Minority Report [AC July ’02] because we’re not talking about the future. We’re in the world that we all live and breathe and work and play in. We’re letting these horrendous events come into our own backyards.”

The preproduction period on War of the Worlds was unusually brief. “Steven and I read the script on the Fourth of July last year and decided right then to make the movie,” recalls Kaminski. “We got a green light in August and started shooting in November in Newark, New Jersey. So the primary challenge was figuring out how to put a film of this enormous size together in such a short time. In fact, we just finished shooting in the middle of March! And the film has more than 250 effects shots, so you can imagine the pace at which everyone had to work.”

The film’s principal character, Ray Ferrier (Tom Cruise), is a dock worker and divorce' whose children, Rachel and Robbie (Dakota Fanning and Justin Chatwin, respectively), are struggling with their new family dynamic when a devastating attack by alien invaders scorches a destructive path through their small New Jersey town. “The script [by David Koepp] is very well-written and just grips you,” says Kaminski. “It’s a continuous ride that completely involves you with the characters. There’s no confusion as to what’s happening: we’re under attack and we’re trying to survive. So you’re completely captivated by the characters and the horror of their situation.

“There are elements to this movie that are almost pure horror, whereas other parts are more like a straightforward drama,” he continues. “Consequently, when we started to conceptualize the look of the movie, I wanted to begin with some sort of grounding element. For example, when we started at the docks in Red Hook, where Ray is a crane operator, we wanted the camera moves, the lighting, the colors and the wardrobe all to underscore the reality of the setting.

“For early-morning scenes at Ray’s home, a small house somewhere in New Jersey, we made the light slightly bluish to reflect the reality of that environment. Then, as this world is invaded by the aliens, the light changes. The skies go from sunny blue to dark gray, with huge clouds and lightning. If we had to shoot that material on a sunny day, of course, we had to keep all of the direct light off the characters and create the dim light of stormy skies. Fortunately, because we knew the skies would sometimes be replaced by the visual-effects team at Industrial Light & Magic, we were able to leave some of our [light-control] equipment in the frame.”

But sustaining the feel of ominous skies throughout much of the film necessitated more than the mere flagging of sunlight. “We had to carefully plan how certain scenes would be shot,” says Kaminski, “because if the sun was in the wrong place for our purposes, we sometimes weren’t able to take all of the sun out. At most, we could use two 60-by-60s overhead, but those still only covered a certain amount of ground. Logistically, it was better to plan with the assistant director, Adam Somner, so that we could better work with the existing light. However, I must add that this was the first time I actually worked around existing light with Steven — usually we just shoot no matter what! But on this film, if the exterior light wasn’t right, we’d just go inside, shoot an interior scene and then come back out when the light was right.

“For example, in the morning, we might shoot our characters arriving at a location, then move inside to shoot the interior scene, and then, in the evening, move outside again and shoot our overcast sky photography. Sometimes we’d have to stop before the scene was finished and finish it the next day in order to get the right light. Normally, Steven doesn’t like to break up a scene for weather or lighting purposes and carry it over to another day; he likes to finish scenes off. But on this film, he was very interested in maintaining a specific visual continuity. It’s a story point that the skies are getting progressively darker, and Steven understood that if I didn’t have to fly huge blacks overhead to block out the sun, we could move faster. Additionally, if we didn’t have to replace the sky in a shot, we could save some money. So there were both logistical and financial reasons for our strategy.”

War of the Worlds was shot in standard 1.85:1 with an assortment of Panavision cameras and Primo lenses, and an essential ingredient in the visual plan was the use of different film stocks and Technicolor’s ENR silver-retention process. “Most of the day work was shot on Fuji film stocks, and we used Kodak [Vision 500T] 5279 for the night work,” says Kaminski. “I adore Fuji stocks for day exteriors; the colors have a slightly more pastel quality. I used Fuji Reala 500D [8592], which is a bit grainy in a nice way, and I also used Fuji Super F-250D [8562] and Super F-250T [8552]. I shot every¬ thing else on 5279.

“At Technicolor, I’m using ENR at an IR of 75 on the prints. I love what it does to the blacks and the quality of the shadows. It does desaturate the color somewhat, but [color timer] Dale Grahn and I know each other so well that he knows he has to automatically put more color into the positive. I love what ENR does to the shadows and the highlights, but I don’t necessarily want to desaturate this picture; by putting a little more color into the print, we’ll desaturate that color somewhat [with ENR] and end up with a color level similar to what we’d have if we hadn’t used ENR, but the contrast will be different.”

As alien “tripods” begin laying waste to the Ferriers’ town, the locals attempt a mass exodus. “There’s a night sequence that we shot at a ferryboat location right on the Fludson River, in a little town called Athens,” explains Kaminski. “I didn’t use blue for that night lighting; I wanted the night to feel more neutral. Later, for the big battle, I made the night look bluer because I knew we’d have a lot of interactive explosions of warm light, so I could afford to create a heavier contrast between blue and orange. But the ferryboat was practically illuminated with warm light, and I didn’t want to create a big contrast between that light and a blue night look.”

David Devlin, Kaminski’s longtime gaffer, explains, “We rigged several hundred Par 36 Fay lights on dimmers around the hull of the ferry. That quickly became quite a lot of amperage, so we had to also bring in a couple of 1,400-amp generators and plumb the exhaust out. Underneath the ferry’s deck, we used 10 LumaPanels, 4-by7-foot 28-tube T8 fluorescent units, as ‘practical’ fixtures. You can actually see them pretty prominently in the movie, so we added some green gels to them to give them a slightly dirty look. For that sequence, we also had two BeBee Lights; one was positioned on a barge and the other worked the shore. On another barge, we had three Condors with Dinos and 20K beam projectors. The Dinos had Firestarters on them and also acted as white moonlight.”

“Janusz has really good instincts,” continues the gaffer. “When we scouted the ferryboat location, he immediately thought we had to put some lights across the water, but we were looking at about a half mile of water! We ended up placing 40-watt lightbulbs every 3 feet for about 950 feet; we put posts in the water and strung the lights across them, adding little putt-putt generators every few hundred feet to power them. The water would never have worked [as a visual element] if something hadn’t been reflected in it — it would’ve looked dead. Those lights were quite effective, and in some ways they were a better solution than just having a BeBee out there, because that would’ve created just one highlight. This way, we got a huge number of highlights and tied them into the look of the boat, which had Par lights ringed around its exterior.”

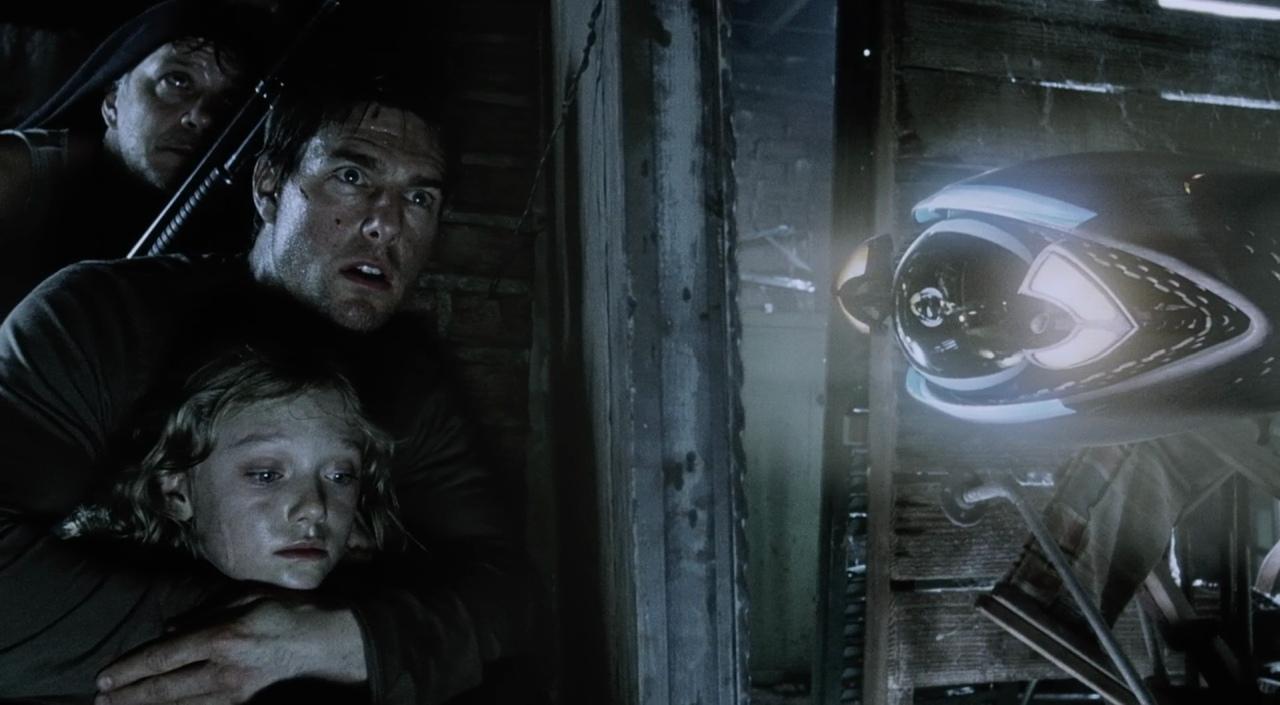

The humans’ hope that the ferry will provide safe passage quickly fades when the boat is attacked by an alien tripod that emerges from the water. “As the aliens attack, we introduce much more color into the film,” says Kaminski. “The tripods have lights and a laser beam, so they’re very colorful — you see a lot of purple, blue, green and red. On this film, I played with color a little more than I normally would. Because it’s very much a horror movie, I was able to play with the angles, quality and color of the lighting more than I would on a straight drama or action film. The movie is somewhat stylized because of the genre, so we could afford to make the lighting more stylized.

To create the interactive lighting from the attacking aliens, New York gaffer Jim Richards and key grip Jim Kwiatkowski assembled several custom rigs to create specific effects. Devlin explains, “For the ferryboat attack, we used six 7K SyncroLights for the interactive lights because of their remote-control and gel-changing ability. We mounted those on a 120-foot construction crane and controlled them remotely with a Wholehog III [Flying Pig System’s dimmer-board console] in order to emulate the searchlights from the tripods. For close-up work, we used Mole 5K beam projectors on Condors and atop the boat. This is the sequence in which we first use a lot of colored light for the alien tripods — lavender, amber, steel blue and a sort of golden yellow.”

One of the most challenging sequences in War of the Worlds was the final battle between the human army and the alien ships, which takes place in a large valley in Virginia. The sequence isn’t just a visual-effects extravaganza, it also marks a key moment in the Ferriers’ own survival. “The battle actually begins with a 17-minute sequence in a basement,” explains Kaminski. “It’s night and there are no lights, so the lighting is completely unmotivated. We had light coming in between boards and around corners, and shafts of light coming in through windows. It’s totally theatrical, but because of the type of movie this is, we knew we could get away with it.”

When Ray’s son decides to leave and join in the fighting, Ray has to decide whether to stop him or stay and protect his frightened daughter. The sequence involved location work in Virginia and soundstage work in Los Angeles, where the farmhouse and sections of the battlefield were re-created. “We started the scene in Virginia on an existing location, but it was very difficult to work there because the weather was just atrocious,” says Kaminski. “On top of that, at the beginning of the sequence, we had several hundred actors, extras and vehicles all going up the hill toward the battle. It was a huge sequence to light, so I suggested we shoot it over several days at dusk, because we only needed about three hours of shooting time to do the scene. We knew that as soon as the sun went down and the night light became non-directional, ILM would be replacing the skies and adding interactive explosions. So over the course of three nights, we used five or six cameras to capture the action. In that fashion, we were able to get the work done in about 25 minutes each day, averaging about 17 shots in those 25 minutes. We’d do one shot and then quickly move the camera to another position. The look is very interesting because it doesn’t feel like daylight, but it isn’t quite night, either.”

In Los Angeles, a massive night-exterior replica of the farmhouse and sloping meadow (which includes a small pond) was built onstage at 20th Century Fox. “[Production designer] Rick Carter created an amazing exterior set that connects directly with the meadow scene where Ray discovers what’s really happening to the world around him,” says Kaminski. “Rick created a little lake and river and then elevated the set so there was a little bit of a slope to the land, where he then put in the farmhouse and barn. Everything was covered with beautiful green grass, and it looked so realistic and beautiful.”

Adds Devlin, “At one end of the stage, they took the floor out and built the set down into the pit, and that’s where they had the pond. From that point, they built a hill that led up to an old farmhouse. From the bottom of the pit to the top of house was probably 35 feet, so by the time you got to the high end of the stage, the set was literally built into the perms. To simulate the soft dusk feel of the location photography in Virginia, we rigged the stage 360 degrees with 70 LumaPanels, which gave us a good amount of ambient light everywhere. Even though the LumaPanels are only 5 inches deep, the camera was always just on the edge of framing in the bottom of those lights. What’s marvelous about LumaPanels is that they have louvers that keep the light contained, so even though we had fairly broad areas of light, it was kept specific to where they were aimed. That allowed the light to fall off naturally onto the backdrop without requiring a lot of flags. We were able to do 360-degree shots without camera shadows and without light spilling from one corner of the set to the other.”

To shoot the more action-intensive portions of the night battle, the production moved to Mystery Mesa, an enormous valley ringed by hills that lies northeast of Los Angeles. “That’s where we did all of our more complicated action and pyrotechnics,” says Kaminski. “Naturally, all of these different locations had to seamlessly match, and the lighting and art direction greatly contribute to that. Because we were lighting at night, I didn’t want the light to fall off into blackness. When you light a large exterior at night, you usually put a large light on one side of a hill and have it fall off into black, but for this scene, I wanted the light to continue. It never really falls off into blackness in the frame. When you look at the frame, you can see the 300 extras coming toward the camera. It’s definitely ‘Hollywood’ and ‘lit,’ but it’s literally lit for miles. The eye can see deep into the distance. That was an interesting and challenging concept that cinematographers seldom get a chance to execute — we were lighting the meadows, the hills and the empty fields. Having everything lit instead of lighting a specific area really gives you a sense of distance. People aren’t emerging out of the blackness, because the light never ends!”

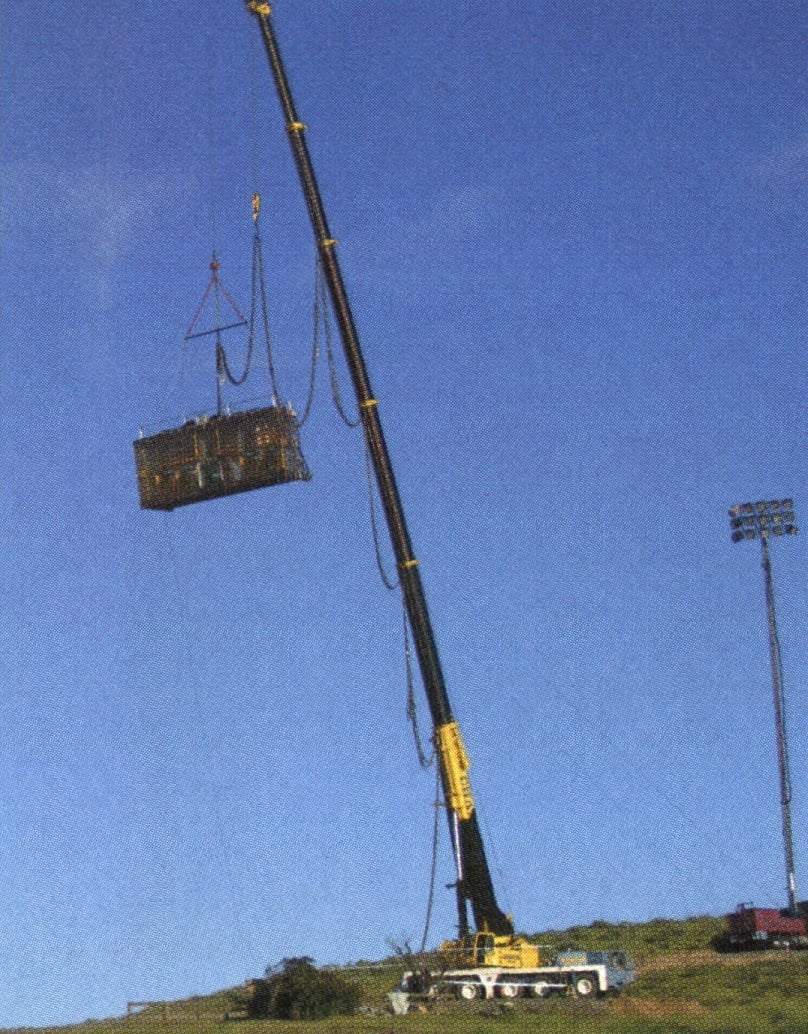

For special lighting effects, rigging grip Charley Gilleran’s crew built several massive lightboxes and suspended them from construction cranes. “When David hit a button, we’d get a huge burst of bright light that was yellow, blue, purple or whatever,” says Kaminski. “It felt like the battle was happening 500 feet behind us and we were just getting the residue lighting, which illuminated the actors watching the battle.” Adds Devlin, “At Mystery Mesa, we had six 15-head BeBee lights and three construction cranes that each had two different custom lightboxes on them: ‘Box A’ had six 36-light Dinos with 1,200-watt Very Narrow Spot Par Firestarter bulbs in them, as well as four 500K Lightning Strikes units. Those acted as interactive lighting sources for explosions and fire effects. ‘Box B’ had four 36-light Dinos with the same Firestarters and four 20K Mole Beam Projectors, as well as four 500K Lightning Strikes.

“We had different boxes because we wanted different kinds of throw,” Devlin continues. “The 20Ks have a wonderful throw; we designed those boxes to throw light about 700 feet. The other box had to throw 500 feet at the most, and the Firestarters were perfect for that. However, because the 20Ks have such large filaments, they’re a bit slower when you try to flicker them. They worked quite well, but in hindsight I think I would’ve gone with just Firestarters, because their ability to flash on and off quickly is pretty incredible. Lightning Strikes units supplied wide, instantaneous flashes but with less effective throw.”

The lightboxes were suspended from three 165-ton cranes with 196' extensions that “enabled us to get high enough to stay out of frame as much as possible,” says the gaffer. “Even though most of the sky was replaced, we tried to keep the lights out of the lens so we wouldn’t get flares. In addition to the big cranes, we had five 80-foot Condors loaded with whatever Lightning Strikes units we had left. Those needed to be mobile so we could move them in for close-up work.”

Kaminski shot the battle on 5279, and with such a vast area to light, he chose to color his lights by gelling fixtures and applying corrections in the lab. He explains, “As the battle unfolds, you see explosions of various colors. The U.S. Army has decided to fight the aliens with artillery and missiles, so there’s a lot of action creating different colors. That allowed us to create various interactive lighting effects — red explosions, green explosions and blue explosions — as well as lots of firelight.” Devlin elaborates, “To create the interactive effect of fire and explosions, we needed to warm up the Firestarters in our lightboxes, and because the BeBees we were using for overall ambience were HMIs and we didn’t want them to be too blue, we needed to warm them up as well. However, we knew that adding Full CTO and possibly more to all of those fixtures would make us lose almost a stop of light. Therefore, Janusz decided to shoot the Mystery Mesa battle clean and have the lab time in the 85 filter we desired. That way, we gained a stop, which helped the BeBee lights kick ass from up to 1,200 feet away. We did, however, apply some enormous swatches of Vi CTO to the front of the lightboxes to warm up the Firestarters, and we made individual gels for the Lightning Strikes.”

Kaminski notes that the expertise of his key crewmembers and their familiarity with one another was integral to the success of the War of the Worlds shoot. “Having David Devlin, Jim Kwiatkowski, [A-camera operator] Mitch Dubin, [A-camera first AC] Steve Meizler, [A- /B-camera and Steadicam operator] George Billinger and [B-camera first AC] Mark Spath helped me move through a movie like this with the necessary speed, because we didn’t have to invent a language or relationships. After several years of intensive work together, I don’t have to be very specific with them when we talk things out, and that certainly makes my life much easier.”

Unit photography by Andrew Cooper, SMPSP; Frank Masi, SMPSP; Frank Connor and Miles Aronowitz.

Tech Specs

- 1.85:1

- Panavision cameras

- Primo lenses

- Fuji Super F-250D 8562, Super F-250T 8552, Reala 500D 8592;

- Kodak Vision 500T 5279 ENR

- Process by Technicolor