Chase, Crush and Devour in The Lost World: Jurassic Park

Steven Spielberg and Janusz Kaminski team up to terrorize movie audiences with a darker, scarier sequel to Jurassic Park.

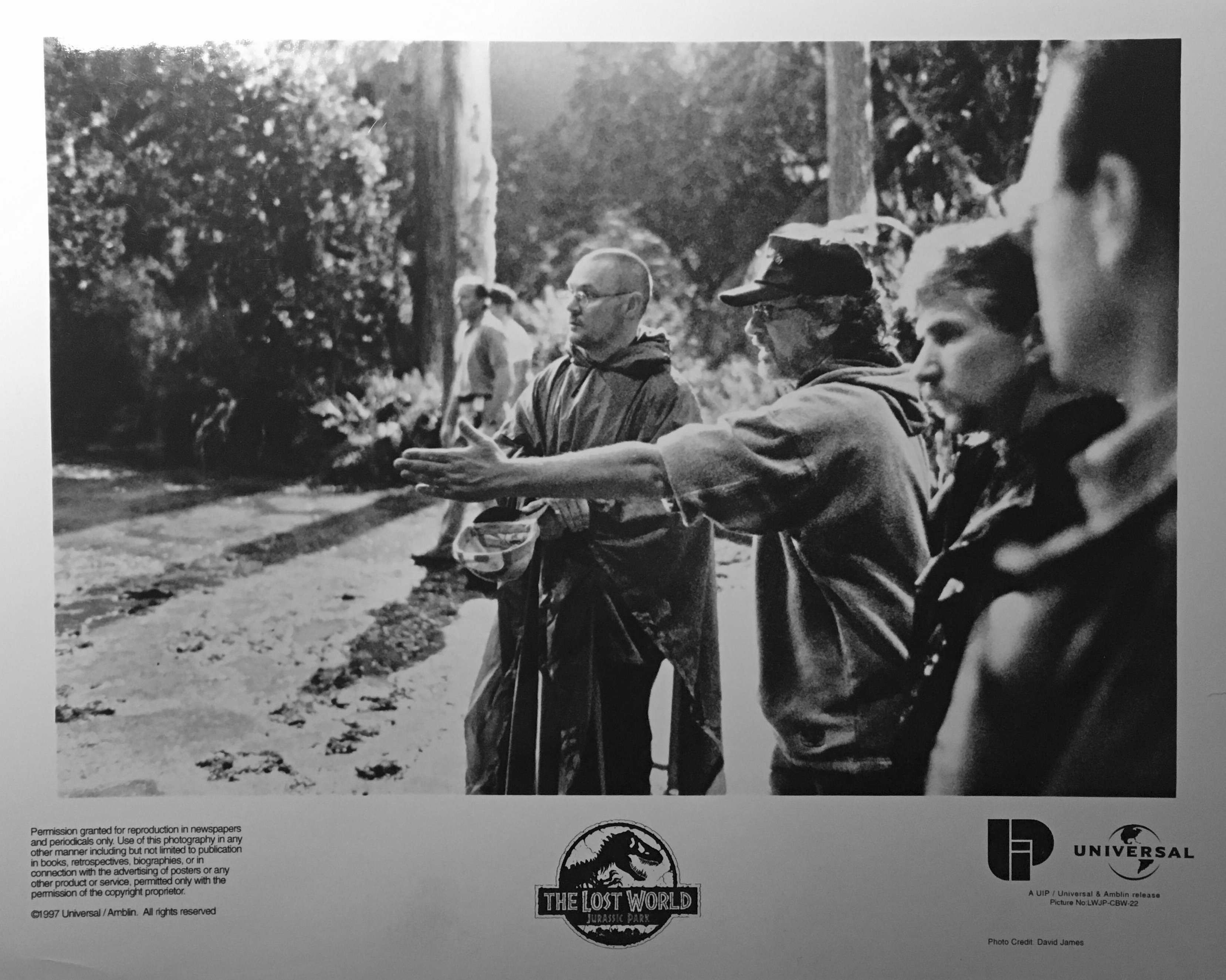

Unit photography by David James, courtesy of Universal Pictures.

For film fans around the world, the credit line "A Steven Spielberg Film" heralds the promise of cinematic spectacle. As one of the most naturally gifted and successful directors of all time, Spielberg has continually upped the ante for himself by helming a seemingly ceaseless string of wildly popular and critically praised pictures: Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the Indiana Jones trilogy, E.T., The Color Purple, Jurassic Park, Schindler's List. But with each new project, the director must confront the pressure of satisfying the viewing public's ravenous appetite for new thrills. As Spielberg himself concedes, "They expect more than I could ever possibly give them."

With The Lost World, Spielberg faces another difficult challenge: to create a compelling sequel to Jurassic Park, one of the biggest box-office blockbusters ever. It's one thing to have a monkey on your back, but a Tyrannosaurus Rex can cause some serious spinal stress. "One of the most overwhelming questions that people have asked me directly in the past few years was, 'When are you going to do a sequel to Jurassic Park?'" Spielberg says. "I've heard that for the past 15 years about E.T. as well, but I've been steadfast in my desire never to produce or direct an E.T. sequel, because it was such a personal film for me. I had a tough time saying no as steadfastly to something that is exploitable as Jurassic Park — and when I say that, I mean exploitable in the sense of pure adrenaline, excitement and adventure."

“My references were things like King Kong, Godzilla, a couple of Roger Corman and Alfred Hitchcock films, and a lot of 1950s monster movies, like The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, Gorgo, and all of those other ‘chase, crush and devour’ films.”

– Steven Spielberg

The premise for the new film was dreamed up by Jurassic Park author Michael Crichton, but screenwriter David Koepp had to employ some deft sleight of hand to skirt around a few nagging loopholes left over from the original picture's story. As Jurassic Park fans will recall, genetically engineered dinosaurs were cloned from ancient DNA by short-sighted scientists on an island off the coast of Costa Rica — with lethal consequences. The Lost World reveals that more of the giant animals were manufactured on a second island, where a hurricane has wiped out the breeding facilities and allowed the prehistoric beasts to run wild.

Still hoping to capitalize on their investment, the amoral leaders of InGen, the corporation that bred the dinosaurs, have sent a group of hunters to the second island to round up some of the creatures and bring them back to the U.S. mainland, where they can be exhibited for commercial gain. Meanwhile, InGen's ousted founder, John Hammond (Richard Attenborough), has turned over a new philosophical leaf after surviving the dinosaur debacle at his theme park. In the hopes of learning more about the prehistoric beasts "for the benefit of mankind," Hammond has dispatched a team of scientists led by paleontologist Sarah Harding (Julianne Moore), who happens to be the girlfriend of chaos theorist Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum), another survivor of the Jurassic Park fiasco.

Mindful of the dangers that await his paramour, Malcolm trails her to the island, where the scientists and hunters soon square off against each other. But when the dinosaurs begin to get surly, the two groups of humans must join forces to ensure their own survival.

According to Spielberg, the new film has a more aggressive edge than Jurassic Park, a slant that is apparent in the visual style. "There are more 'land sharks' in this movie, and more lives in harm's way," he notes. "In addition, the photography on this film is much more contrasty. From a lighting standpoint, we took a sketchier approach on this film than we did on the last one. On Jurassic Park, we let the dinosaurs reflect more light, but on this movie we let them absorb more light."

Accepting the challenge of creating a distinctive photographic style for the film was cinematographer Janusz Kaminski, who received a slew of accolades, including an Academy Award and an ASC Award nomination, for his superior black-and-white work on Schindler's List. Kaminski faced the unenviable task of succeeding director of photography Dean Cundey, ASC, whose smooth integration of traditional camerawork with mechanical effects and computer-generated imagery on Jurassic Park earned him the considerable admiration of his peers. Explaining the change, Spielberg says, "I offered the film to Dean first, because I would certainly never pull a sequel away from a great cameraman. Dean has done nine movies that I've either directed or produced, but he was off preparing to direct a picture when I asked him about The Lost World.

"After Dean told me he was unavailable, I went straight to Janusz. As a cinematographer, Janusz is not 'one size fits all' — he's much more of a chameleon. He takes the stories he does very seriously, and he marks up the scripts. He tells a cinematography story on top of the writer's or director's story, and he designs the photography according to the beats and measures of the narrative. Because of that, he's going to shoot differently on Jerry Maguire than he would on The Lost World. Over the course of his career, Janusz has put together a collection of amazing and completely different looks from picture to picture."

“Working with Steven is very fulfilling, because he has brilliant ideas and he's always open to input from the people around him. In addition, you have the benefit of his stature as a filmmaker, which really helps on a movie this size.”

— Janusz Kaminski

Kaminski's association with Spielberg began shortly after the 1989 airing of Wildflower, a Lifetime television movie he shot for actor/director Diane Keaton. His work so impressed Spielberg that the director hired him to shoot the Amblin' television production Class of '61, which in turn earned Kaminski the chance to photograph Schindler's List. The cinematographer's resumé also includes The Adventures of Huck Finn, Tall Tale, Little Giants, How to Make an American Quilt and Jerry Maguire. He is currently collaborating with Spielberg on Amistad, a historical epic based upon the true story of a 19th-century slave ship rebellion.

The cinematographer says that his priority on The Lost World was to come up with a visual approach that would distinguish the film from its predecessor. "Jurassic Park was very much like an amusement park ride," Kaminski notes. "The images were brighter, more colorful and more friendly. This film is much more moody and violent. Steven was not in the same frame of mind as he was when he did Jurassic Park. His last project was Schindler's List, and I think his sensibilities are a bit darker now. The Lost World is still a popcorn movie, but it's more of a thriller like Jaws. In fact, we used many of the tricks from that movie — for instance, the camera might be locked in on someone's face, and all of a sudden the focus will rack back to a huge dinosaur's head behind them. When the person turns, we then cut back to a shot over the dinosaur to capture the fear in the character's eyes. It's very scary."

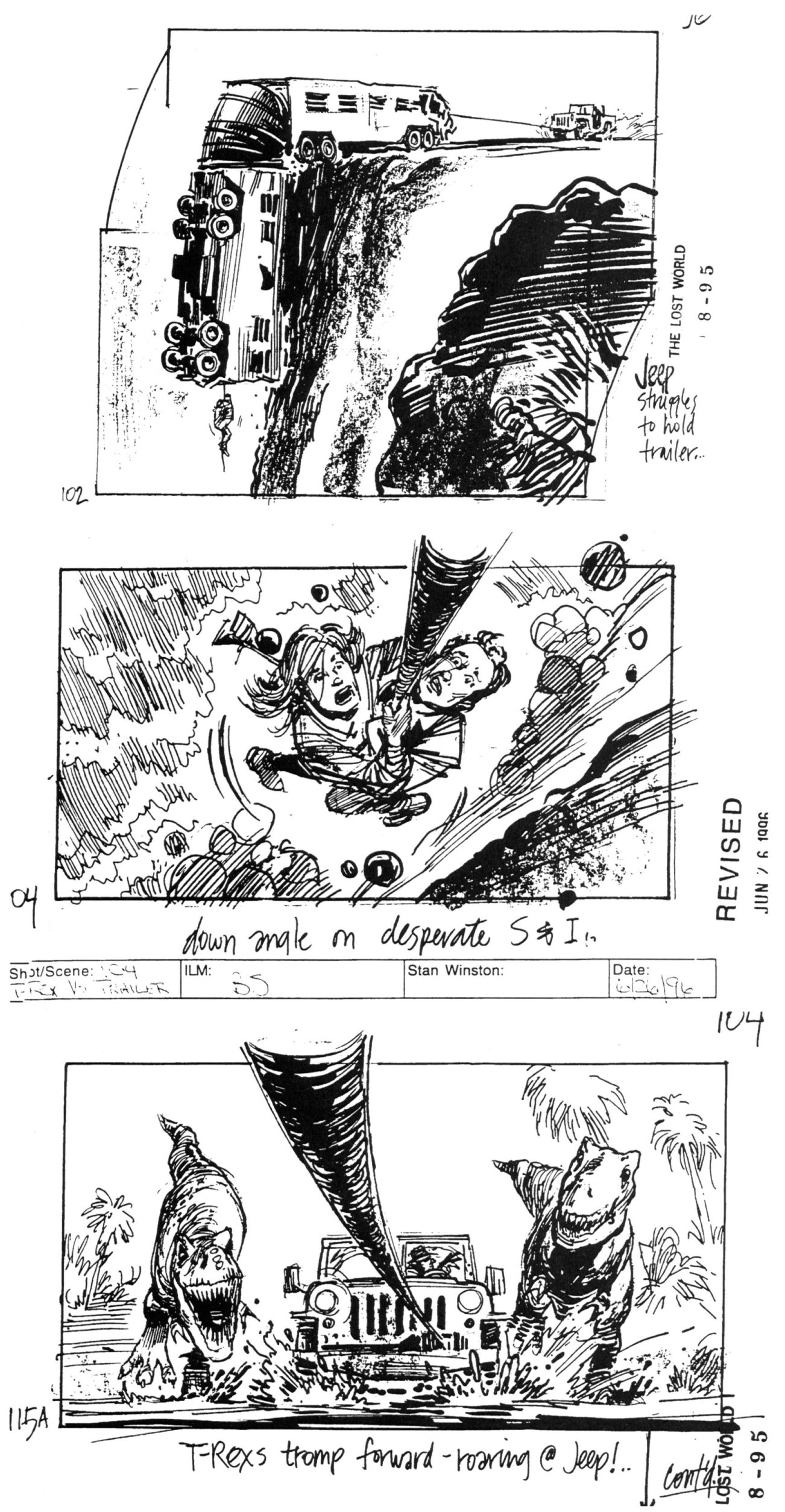

In planning the look of The Lost World, Spielberg made extensive use of storyboards, which helped him to map out the film's complex action set-pieces in a clear, precise manner. "We had almost 1,500 storyboards on this picture," he reveals. "I shot them pretty accurately. I would say that 80 percent of the storyboards are in the movie, but that's mainly because the film is one set-piece after another. You can't wing things like that, because every department needs to know, often months in advance, what to prepare for those shots. For a complicated special effects and mechanical effects movie like The Lost World, the storyboards are a priority. On a story like Schindler's List or Amistad, storyboards really get in the way of discovering how to tell the story on a daily basis. I never do storyboards for dramatic scenes, but I will do storyboards for anything involving action and logistics. When you have a sequence involving stampeding dinosaurs, you have to know where the actors are going before you consult with the effects experts about where to put the dinosaurs."

Although the director found inspiration for the film's style in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's book The Lost World, he also referenced a variety of vintage films for visual cues. "Older movies are always running through my mind," he says. "On this film, my references were things like King Kong, Godzilla, a couple of Roger Corman and Alfred Hitchcock films, and a lot of 1950s monster movies, like The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, Gorgo, and all of those other 'chase, crush and devour' films."

Kaminski says, "Steven said to me at one point, 'I want this to look like an old glossy Hollywood movie, but I don't want it to feel dated.' So that was basically the approach. We did include a lot of homages in the movie, though; there's even one shot of Japanese tourists running in front of a big CGI T. Rex!"

The cinematographer adds, however, that he had some of his own visual references in mind. "Alien and Blade Runner were the two films I looked at," he says. "The biggest compliment Steven gave me was during the shoot. He came back to the set after doing some cutting, and said to me, 'Man, it's so moody, it looks like Alien!'"

The cinematographer began his pre-production planning by sitting down for detailed discussions with ILM visual effects supervisors Dennis Muren, ASC (full-motion dinosaurs) and Michael Lantieri (special dinosaur effects). "It was actually very easy to shoot all of the CGI composites, because the guys at ILM are just amazing with that sort of stuff," Kaminski enthuses. "There were times when we had a flare in the lens, and I would say, 'Dennis, there's some flare there, is that okay?' And he would reply, 'Well, it's never been done before, but let's try it!' We have some shots in the film in which we tilt down from the sun into the ground, where there are some activities going on. All along, Dennis was planning to put in a silhouetted image of a CG dinosaur.

"There were almost no restrictions in terms of what I could do, to the point where occasionally it was much easier to light," he adds. "For example, if I had a big strong backlight on a soundstage, I could flag the light so it wouldn't flare the lens, and later on Dennis would just take the flag out digitally. The man is really a genius."

In regard to the computer-aided effects work, Spielberg submits, "It helped that we were working with a lot of the same people at ILM who had worked on Jurassic Park. They really wanted to bring the dinosaurs back to life, but they wanted to make them look even more natural than they did in the first film. Because this film had more action and more CGI dinosaur shots — about 50 percent more than the first film — they were really excited. They weren't so much trying to top the first film, but just trying to do it differently without repeating anything we'd done before."

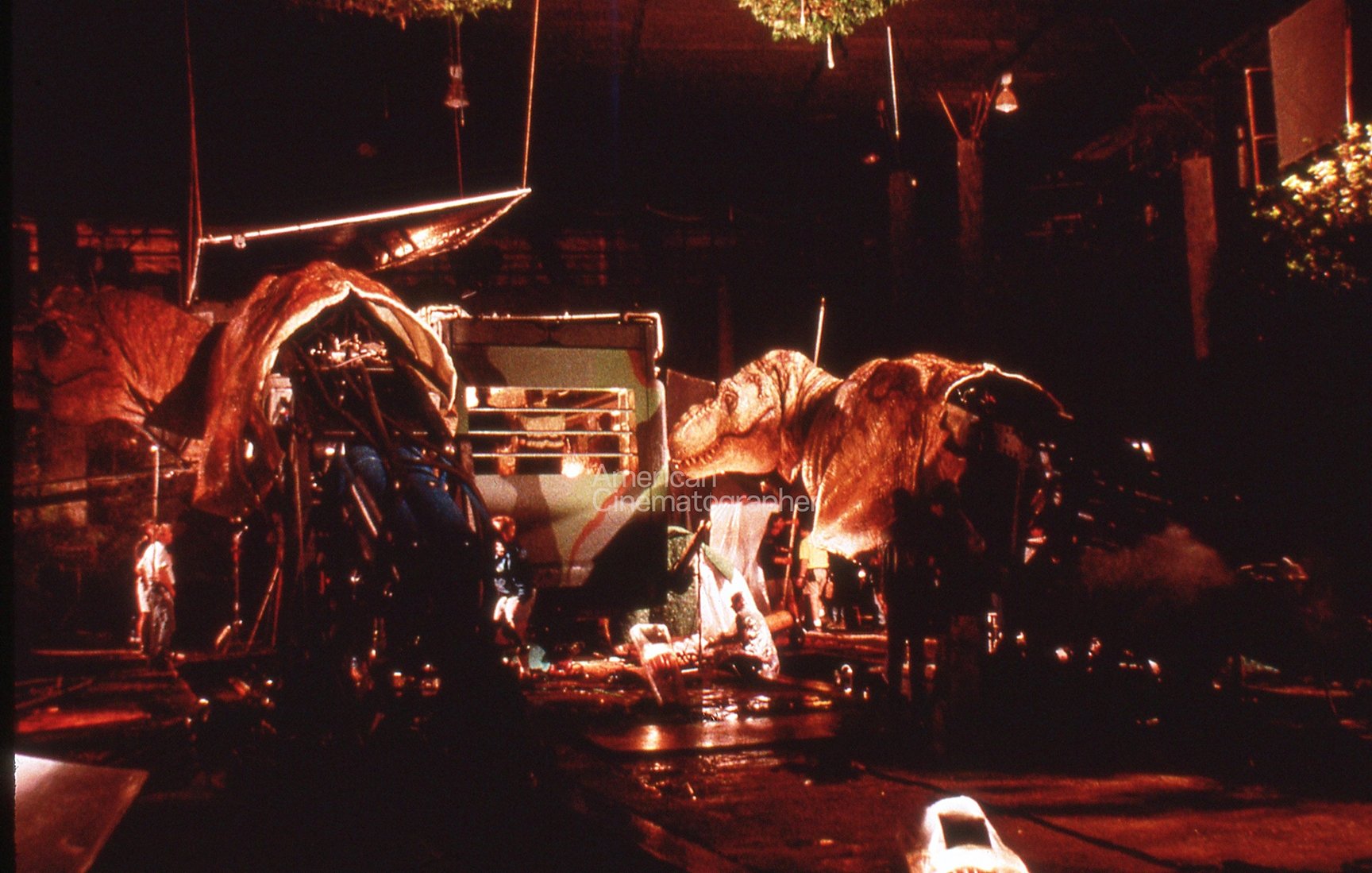

Spielberg and Kaminski also consulted closely with mechanical creature effects wizard Stan Winston, who created all of the film's frighteningly life-like animatronic dinosaurs, including a pair of life-sized T. Rexes that cost $1 million apiece. Each of the computer-controlled Rexes required a team of 10 puppeteers to operate, and could generate up to 2Gs of force while moving. "We had to find out what kinds of movements the life-sized T. Rexes could do," Kaminski says. "They looked so real that we were scared of them; in fact, they were very powerful animatronic creatures, and we were warned not to get too close to them when they were activated, because if there was a malfunction, they could literally kill someone. The T. Rexes could move very fast, and they were capable of breaking a stage wall. We couldn't use any radios or electronic devices near them either."

Kaminski and camera operator Mitch Dubin conducted a variety of different photographic tests in prep. The cinematographer briefly flirted with the idea of using Deluxe Laboratories' CCE silver-retention process, but explains that ultimately, "I realized that CCE wasn't the right process for the movie. Everything was becoming too hard-looking; it would have been a bit too much for the summer thriller audience. We didn't want to scare them too much!"

Kaminski also vetted Kodak's new Vision film stocks. "I tested the new Eastman Kodak Vision 320 stock, and the 500 as well. Based on those tests, I shot the film primarily with the 500 ASA 5279 stock. I also used 5293, which is rated at 200 ASA. The Vision stock is amazing. It's virtually grainless, and it has incredible latitude in terms of both over- and underexposures. It holds highlights beautifully.

"Every time I had a situation where I needed a bit more contrast, or when I was doing day interiors, I would use the 93," he continues. "I also used the 93 for the ILM work, because we did some of that on 4-perf. Most of the ILM work was shot with VistaVision, and at that point it doesn't really matter which emulsion you use, because there is no degradation of the negative. But when you're shooting 4-perf and start doing opticals, you can get generation loss. So for that stuff you need a really fine-grain negative. All of my night interiors and exteriors were shot with the 79."

Kaminski's camera package consisted of three Panavision units, including a Platinum and a Panastar. "We also had a Beaumont camera, which is a lightweight 8-perf camera that you can mount on the Steadicam. We used regular VistaVision for our dolly work or stationary work, and we also had a handheld Arriflex."

The film was shot in the 1.85:1 format to allow maximum headroom for the dinosaurs. Kaminski says that he photographed the entire film with Primo prime lenses, most often at the wider focal lengths preferred by his director. Spielberg notes, "I like to use wide frames to create suspense — shots where the characters are small and vulnerable in the frame, surrounded by the environment. I also like to have people's backs to the camera. In those types of compositions, the threat presents itself in every possible direction — you never know where something's going to come out of the frame to attack.

"We generally found ourselves either working with the 20mm, 24mm or 29mm lenses, or jumping right to the 85mm or 100mm for shots involving the dinosaurs and their victims," the director adds. "We didn't use the 50mm that much, because I've found that the animals always look better when the focal plane is compressed. When you shoot large animals with wide lenses, their heads are big, but their bodies could be diminished to the vanishing point, and they look kind of puny as they go off into space. It's much scarier when you use longer lenses to compress the people and the vehicles. I did the same thing on the first movie. For example, I used a longer lens to compress the T. Rex and the Ford Explorer with the two kids inside. On this film, I used a similar technique for the scenes involving our twin T. Rexes and any of the intended victims or vehicles."

The Lost World was scheduled to be shot over 72 days, but the filmmakers managed to complete production in just 66. "The pace was so hard that at the end of the week we'd all just hug each other and say, 'Whoa, what just happened to us?'" Kaminski relates with a grin. "There was a lot of energy, but that's the way Steven likes to work, and he brings it to the screen. Personally, I love working that way, but it could sometimes be hard on the focus puller, Steve Meizler, who did a great job despite the constant pressure."

The quick pace was partly due to Spielberg's decision to work without a second unit. "I enjoy doing my own second-unit work, and I mostly try to do that," Spielberg says. "On the Indiana Jones films, I always had a second unit that would take my storyboards and shoot portions of chases and things like that. But recently I've found more satisfaction and control in doing my own second-unit footage. When I farm something out to a second-unit director, invariably when I see the dailies I'll like some of the shots, but not others. Then I have to send them back for take two and take three, which costs the company more money. I've found that I can save a lot of money by shooting my own storyboards, because I know what I want and I can try to achieve it without going back a second and third time."

The film's logistical complexities necessitated careful planning and organization. Exterior footage was shot on location in Eureka, California, with some additional work at the Pasadena Botanical Gardens. Sets were shot on four soundstages at Universal Studios: Stages 12, 23, 24 and 27. "Stage 12 was where the hunter's camp was built," Kaminski explains. "On Stage 23, we built this big ravine that some characters are chased into by the T. Rexes, as well as a waterfall. Stage 24 was the T. Rex stage, where we had sets that were built around the animatronic dinosaurs. On Stage 27, we had a 'cliff' constructed for a big set-piece in which the scientists' mobile lab is pushed toward the edge by a pair of Rexes."

The filmmakers' new approach on The Lost World is most clearly evident in the picture's lighting style. While Kaminski did deploy large, soft lighting units for general key and fill, he augmented the look with a variety of more direct sources, including two very rare types of units — a pair of old-fashioned "sun arcs," and a vintage set of T-5 beam projectors. These unusual tools were tracked down with dogged determination by key members of Kaminski's lighting crew. Expert gaffer David Devlin recalls the quest: "We really played a lot of things in backlight, and we used these old sun arcs pretty extensively. We first heard that we were doing the project while we were still working on Jerry Maguire, and one day Steven visited us on the set and told us how much he wanted to use sun arcs, which he had previously employed on 1941. I'd never heard of these lights before; they're old searchlights that were used during World War II, and maybe even before that. They're basically arc units that project a beam similar to what you'd get with a Xenon light, but these use carbon arcs that feed right through the front of the lamp. They also have a mirror made by Bausch & Lomb that's right behind the flame — the quality of the light is beautiful, and the mirror really focuses the beam. It's a very interesting look.

"The problem was that these lights were in extremely short supply. At one time there were 30 or 40 of them, but they slowly died out in America. In the 1950s, movie companies would send them out on location projects like The Good Earth, and they'd just mysteriously vanish. I started looking all around for them, and I heard rumors that there were some in China. I even began searching for them on the Internet. Finally, my best boy, Larry Richardson, actually came across a pair of old, decrepit sun arcs at Sony. Steven agreed to have the units refurbished at Universal, and we used both of them on the picture."

Although the sun arcs proved to be effective as backlight sources, their sheer bulk — 275 pounds apiece and 43" in diameter — limited their usefulness in certain situations. This led the filmmakers to hunt down a set of T-5 tungsten beam projectors, which create a strong, searchlight-type beam. The production rented the only set of T-5's existing in the U.S. from ETC, a Hollywood-based manufacturer of theatrical lighting instruments. "The lights once belonged to Universal, but about 10 years ago they sold them to ETC, and they've been kicking themselves ever since!" Devlin states. "We had literally every one of these lights that was available in Hollywood."

The T-5 units proved to be invaluable in a variety of different ways. Says Devlin, "They're a bit like tungsten Xenons, but the look they create is more organic, because they're not computer-designed lamps. A Xenon has a hole in the back of the reflector where the bulb goes through, and you can see where that hole is because the reflector is so well-designed. The result is a beam that can sometimes look a bit like a doughnut. The T-5's utilize a mirror, which is not as precise and creates a smoother beam. In addition, the Xenon uses an arc bulb, which tends to jiggle, whereas these lights have tungsten filaments and a mirror; they create a very steady source with a hard, sun-like punch."

Kaminski and Devlin sometimes used as many as 20-25 of the T-5's while shooting night exteriors. "When we set them up one after another, they gave us a kind of broken pattern of light without using flags or cutters," Devlin explains. "On this film, the camera never stopped moving, which made it difficult to control the light in certain situations, because you can't just use huge flags all the time. That's where the T-5's really saved our skins. You can just set them up in a ring within a stage and sprinkle the light around without having an overall backlight everywhere. The look they created helped to give this film the more gritty feel that Steven and Janusz wanted, and they also allowed us to work really fast, which is the name of the game when you're working with Steven."

Elaborating upon his use of the beam projectors, Kaminski details, "I would stack a batch of them together and use them to outline the T. Rexes. To give the dinosaurs a key light, I used big soft sources. I had these huge softboxes built, which were covered with 12' x 12' sheets of muslin. I would shoot the light off the foamcore and into the muslin to create a beautiful soft source on a large scale. We had built the sets on Stage 24 around the T. Rexes, because we couldn't move the animatronic animals. We had our beam projectors and Dino lights hanging all around the stage, because Steven sometimes likes to change things and shoot from another direction."

Approximately 75 percent of The Lost World was shot on soundstages, but both Spielberg and Kaminski prefer location work. Says Spielberg, "If you're looking for reality, it's a lot easier to use God's light and just augment that with HMIs or arcs than it is to create that look 100 percent artificially on a soundstage. No matter how realistic the lighting looks on a soundstage, it still will look like a stage compared to the real thing. Personally, I like to be outside — or in practical interiors — as often as possible."

In creating "natural" environments on stage, Kaminski found himself "constantly making small improvements. I realized a few years ago that when I go on location to shoot night exteriors, I tend to light things a bit brighter to show them off. I light the forests and I light the environments to show that we're on location. I tend to do the same thing on a stage, but in that situation you have to be a lot more careful, because you're photographing an artificially created set. The moment you start lighting things brightly, it starts to look more fake. The lighting ratios are much different on the set than they would be on location. For example, sunny day exteriors are less contrasty on location and more contrasty on stage, because that helps to sell the illusion that you're in a real outdoor environment.

"On Stage 12, I had four Dinos facing each other on both the north and south wall. On the longer east and west walls, I had eight on each side. David Devlin put frames of muslin in front of the Dinos to create the effect of big softboxes, and we shaped the light with flags. So we had these big multiple units all around the stage, and depending upon the angle and direction of the camera, I would turn on the north bank or the south bank. I would get this really beautiful soft backlight. Working with a 500 ASA emulsion, I would get a stop of T2.8. I shot the whole movie at 2.8 because it's a good stop for night exteriors — about 70 percent of the movie takes place at night, in the rain. Depending on the situation, the fill light would be 1.4 or 2, but no more, because at that point it starts to look unrealistic."

Stage 12 served as the site of a major night exterior sequence in which a pair of the scientists sneak into the hunters' camp to cut their fuel lines and punch holes in their vehicles' tires. The sequence involved a large dolly shot which tracked the actors as they crawled under some jeeps, sabotaged the fuel lines, and then crept past the hunters' tents. "As they're going through, one of the lead hunters is staging a big conference with his associates," Kaminski relates. "We worked from the idea that the hunters had brought a lot of equipment with them, including practical fixtures to light their camp. I set up these portable lighting units that are often used for highway repair work. Each unit had its own engine, and consisted of four mercury-vapor lights attached to a small arm. I had four of those, and I placed them in four different parts of the stage. I kept them uncorrected to create this very dirty blue tone, and I pointed them straight down to create these ugly spots of light. Then I lit the backing and the trees, and also the tents — I put a bit of warm light in the tents and then backlit them a bit as well. I wet everything down and added a bit of fog, and it started to look very real without being too pretty. I also lit the jeep interiors with fluorescents so we'd have a bit of green light coming from underneath the vehicles."

One of the film's biggest set-pieces is a sequence in which a pair of T. Rexes attack the scientists' mobile lab — a pair of equipment-filled camper trailers that are connected by an accordion-shaped rubber umbilical section. As the Rexes batter the two-piece lab, one half of it is pushed over the edge of an oceanside cliff, where it hangs and threatens to pull down the rest of the vehicle. To make matters worse, scientists Sarah Harding and Ian Malcolm find themselves hanging from the dangling end of the lab. A third member of the island expedition attempts to rescue them, but his heroics are jeopardized when the angry Rexes reemerge from the nearby jungle.

Filming of the sequence began on location in Eureka, then continued on Stage 24, Stage 27, and even atop a parking structure at Universal Studios. Shots that involved the trailer and CGI dinosaurs were filmed on Stage 27, while the close-ups of the animatronic dinosaurs were executed on Stage 24. For more shots of the hanging trailer, the crew added a rocky facade to the exterior wall at the Universal parking structure and dangled the trailer from a 95-ton crane; this setup was later duplicated on Stage 27, requiring the production to cut a hole in the stage roof to accommodate the crane.

"We had to shoot that sequence in a variety of different places within one week, using different trailers," recalls David Devlin. "In order to keep the lighting continuity, all of the interior lighting of the trailers was duplicated with the help of a computer program designed by the rigging gaffer, Brian Lukas. The inside of the lab is filled with practical lighting, computer screens, ultrasound machines, and so on; as the trailer is smashed, all of these things go off at certain times. Brian's program was controlled with a computerized dimming board, which enabled us to duplicate any circumstance exactly. The result is like a miniature light show inside the trailer."

A long stretch of the scene was filmed in one continuous take with the help of a 26'-long Chapman crane arm outfitted with a remote head, which tracked the scientists' would-be rescuer as he pulls up in a jeep, attaches a rope to a tree, and runs through the trailer to feed the rope down to Harding and Malcolm. "The whole move was very intricate, and it required extreme precision by the crane operator, the focus puller and the actor," Kaminski says. "As the actor was running through the trailer, the camera was following him very fast; if he stopped, the camera would have knocked him over, because we simply didn't have the ability to stop such a heavy piece of equipment instantly. Also, because we were shooting with a 21mm lens, we had the problem of trying to keep the dolly tracks out of the shot. The track was built into the stage, and we built another piece of stage over the track to cover it. As the camera moved, the grips and other crew members cleared the stage parts so the dolly could get through."

The filmmakers confronted a variety of technical difficulties while shooting the trailer sequence. During the continuous crane shot, Kaminski discovered that a piece of electronic equipment inside the trailer was creating interference. "Every time the camera reached a certain part of the trailer, the remote-control focus would slip and lose focus. We had no idea how to fix it, even after about 15 takes. We were about to give up when we decided to try a remote-focus mechanism provided by our Steadicam operator, Chris Haarhoff. We mounted it on the camera, and for some reason it didn't interfere with whatever was happening. All in all, it took us about nine working hours to get three good takes. It was very grueling."

Adding to Kaminski's headaches was the fact that the scene was supposed to take place in pouring rain. "We were constantly pointing the cameras straight up into the rain towers," he recalls with a grimace. "Gallons of water were being poured onto the lens, so we were having problems with the lens fogging and the rain deflectors dying on us. Steven was saying, 'Dammit, this never happened on the first one! We were pointing the cameras straight into the rain, and there were no problems!' I wound up calling Dean Cundey to ask him if he had ever pointed the cameras straight into the rain. He told me, 'No, we were always at a bit of an angle.' The problems were only happening when I was pointing straight up, because there was simply no way to get rid of the water.

"In terms of the lighting, it helped to put backlight on the rain; if you don't do that, you'll have a hard time seeing it. As the trailer was being pushed toward the edge of the cliff, I lit its interior with bluish-green fluorescent units. It created an interesting effect, because the fog headlights on the trailer were very warm. The strong tungsten backlight that was outlining the edge of the cliff, the trailer and the rain was a little bit bluish; I only used a ¼ blue on the tungsten beam projectors. I didn't want to go too blue and get too clichéd with the night exteriors. So you've got this slightly blue backlight; a strong bluish-green light coming from the trailer, which is glistening from the backlight; and these warm headlights. It's a very pretty picture, but at the same time it's a very dramatic and suspenseful sequence."

Water again posed a problem during filming of a scene in which several scientists are chased through a ravine by a T. Rex, and must save themselves by taking shelter in a small cave behind a waterfall. The shot was executed on Stage 23 by Steadicam operator Haarhoff. "Chris used the Beaumont camera mounted on his Steadicam," Kaminski says. "He was running in front of the imaginary T. Rex, and in the course of the shot he had to go right through our manmade waterfall, which made the whole thing pretty intricate. The problem was to make the shot without the water affecting the stability of the Steadicam. Michael Lantieri, who is a special effects genius, overcame that difficulty by building a little rain-bar that looked like a huge waterfall, even though it was only giving off about a two-millimeter sheet of water. Just as Chris was going through the waterfall, a grip would extend a flag for a split second to cut off the flow. We later did a matching shot where Chris filmed toward the waterfall from inside the cave as the T. Rex's head popped through.

"It was a night sequence, so realistically there should be no light in the cave," Kaminski adds. "But I lit it in a stylized way, with some backlight illuminating the water in a very ominous way. This huge mechanical head then comes through and starts sniffing around. My thinking was that there might be some strong moonlight backlighting the water, which then would create a soft source illuminating the cave. Of course, when the T. Rex's head comes through the water, we were able to get some shafts of very hard light into the cave as well."

Although Spielberg generally uses Steadicam very sparingly on his films, the director estimates that close to 50 percent of The Lost World was shot with the stabilization system. "Usually, I'll only do one Steadicam shot per movie," he notes. "In Schindler's List, it was the shot that introduces Oskar Schindler in the nightclub at the beginning of the story. I think we used no more than three Steadicam shots in Jurassic Park. But The Lost World is a movie about chasing and being chased, and there's not enough dolly track in the world for all of the acreage we covered. The Steadicam proved to be a very useful tool."

Equally valuable to the filmmakers were Kino Flo fluorescent fixtures. Kaminski says that his extensive use of fluorescent units represented a new experiment for him. In addition to using them to light the interior of the scientists' lab, the cinematographer found that the Kinos lent an interesting ambience to bigger setups as well. "I'd always wanted to use fluorescent fixtures, but I never had the right movie to do it on," he says. "At first, I was a bit hesitant to use them on The Lost World, because I didn't really know how to use them. But David Devlin and the key grip, my longtime friend Jim Kwiatkowski, had worked with them on other projects, and they guided me along very nicely. For example, I might set up a fluorescent tube and start flagging it, but David would tell me, 'Don't flag it, because the minute you start flagging a fluorescent tube, you're narrowing the angle of the light and making it a very hard light. Instead of narrowing the angle, take the fixture further back, because the light's falloff is really fast. If you think it's too bright in the background, don't worry about it, because the falloff is immediate, and it falls off into the shadows really nicely.'

"What's interesting about the fluorescents is that they photograph much brighter than the meter tells you. I might be shooting at 2.8, but the meter would tell me that the light was at 1.4. So I'd think, 'Wow, I'm two stops under. How will it look?' But David and Jim would say, 'Don't worry, it'll look great.' And it always did. With tungsten light, if the meter says two stops under, I know it will be two stops under. But fluorescents are different."

David Devlin elaborates: "Because it's a gritty film, we used a lot of cool white and green tubes, but we also used a lot of other colors as well. One great thing about the Kinos was that if we changed our minds about a color, we could just change the type of bulb without losing the output. If you put a lot of red, green or blue gel on a tungsten fixture, it changes everything, including the quality of the light. We could go from a yellow to a 'super blue' or to 'digital green' to a cool white or even a Kino 32 bulb. Again, it's a quicker way to work."

Devlin adds that the Kinos helped the filmmakers add some drama to shots of the big animatronic dinosaurs in motion. "The hardest thing about lighting the dinosaurs was that they were so big," he testifies. "In prep, I didn't realize just how big they were, and what that meant. Just a turn of the head can move it eight or nine feet, so you have to light for more of a distance. In the first film, they would usually put up a big soft-light that would carry from one spot to another. But if you use a big soft-light, it almost lights things too much, and you can lose some of the drama. On this film, we'd space out Kino Flos and flag them so they would work from position to position during these big moves. Something as subtle as that can make things much more dramatic than if you just have the dinosaur moving through one big, soft light; it moves into the light rather than just passing through it."

Looking back on the shoot, Kaminski offers an enthusiastic assessment of his relationship with Spielberg. "Working with Steven is very fulfilling, because he has brilliant ideas and he's always open to input from the people around him," Kaminski says. "In addition, you have the benefit of his stature as a filmmaker, which really helps on a movie this size. At one point, Steven said to me, 'Hey man, this is a Cadillac with white trims.' And it truly was — I got anything I wanted in terms of equipment and additional crew."

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.