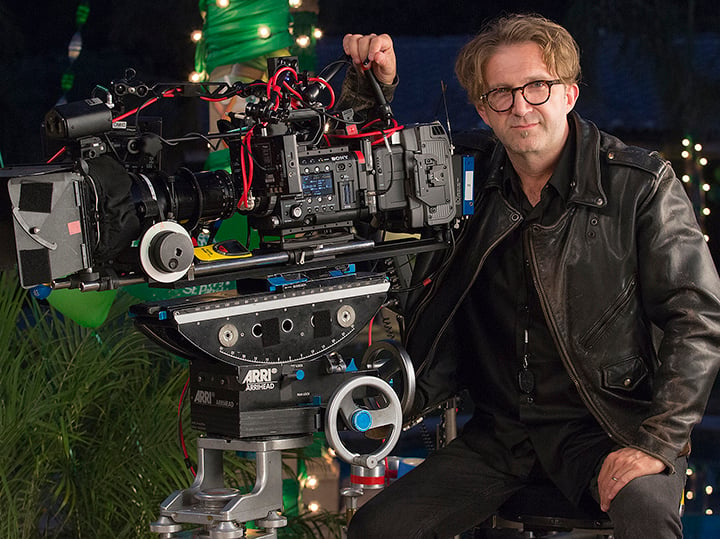

In this episode, cinematographer Steve Gainer, ASC, ASK talks about his work as curator of the ASC’s historic camera collection, which include a wide variety of noteworthy filmmaking tools, from the very first mass-produced motion picture camera to the first digital-cinema units.

As curator of the ASC’s Museum collection, Gainer blends a love of history and cinematography with a talent for engineering and communication into a truly unique experience that bridges the past and present for a whole new generation of filmmakers.

ABOUT THE PARTICIPANT

Steve Gainer, ASC, ASK’s screen credits include the films Bully, Teenage Caveman and Wassup Rockers with director Larry Clark; Mysterious Skin with Gregg Araki; A Dirty Shame with John Waters; and the very R-rated pre-Marvel Studios feature Punisher: War Zone with Lexi Alexander, as well as numerous music videos and television series.

ADDITIONAL READING

ASC Museum Camera Collection Expert photography showcases some of the unusual, unique and rare items in the Society’s archives.

A Brief History of the ASC Clubhouse Discover the story behind the longtime Hollywood home of the American Society of Cinematographers.

ASC MUSEUM MINUTE EPISODES

Bell & Howell 2709 — The first all-metal professional 35mm motion-picture camera.

Cinex 35mm Camera — A French 35mm motion-picture camera from 1925 specifically designed for handheld shooting.

Cunningham Combat Camera Model C — A unique World War II-era unit designed for use by military cinematographers under extreme conditions.

Arri IIB Camera — This 35mm motion-picture camera specifically designed for handheld shooting was used by William Fraker, ASC to shoot the film Bullitt (1968).

TRANSCRIPT

Iain Marcks: Steve, it’s so good to talk to you again. It feels like it's been a while. We’ve kept in touch, but we really haven't had any lengthy conversation in some time.

Steve Gainer, ASC, ASK: You know, we haven’t hung out since packing things up for the restructuring of the building. That was a long time ago.

Iain Marcks: Yeah, it was like 20 years ago. You, me — at first, it was you and Jon Witmer, the former managing editor at American Cinematographer, who's now at Panavision. And I remember Michael Goi [ASC], and Victor Kemper [ASC], and Izzy Mankofsky [ASC] being around the Clubhouse a lot at that time, just, you know, kind of checking in on all the cool stuff we were cataloging and photographing and packing up for storage.

Steve Gainer: Yep. And, truthfully, only now, our recent writers and actors strike has given me a certain amount of freedom and availability that ordinarily I don’t have, because obviously, I work. Let’s call it a year, almost. I have spent a lot of time, and there were certain items that still had not been unpacked, and I'm happy to let you know that we did a fantastic job, and nothing fell ill due to being wrapped up in the bubble wrap for that amount of time. And I was concerned, because it is a petroleum product. But I'm really happy to tell you that everything came out just rosy and beautiful as it was when we packed it away, oh, so long ago. You know, you were I’m guessing 11 then so...

Iain Marcks: It feels like it. No, I was in my early 20s, so I might as well have been 11. You said that you've been working, and I know that you've done some producing and directing lately, but you're still primarily director of photography, is that correct?

Steve Gainer: That's right. I'm primarily a cinematographer. And just prior to the strike, I finished an Amazon show called With Love. I had two other shows that were scheduled to go, one Netflix and one Amazon and both of them vanished into thin air once the strike was announced. So I think the entire industry at this point is, you know, trying to figure out where we are. So I’ve been you know, I've been doing a little bit of my own damage control on this end, because you know, living in Los Angeles is not free. So I have been producing and directing. And I can’t say too much because I'm NDA’d on these things, but I have been producing and directing some pilots for documentary series, which are pretty cool, which don’t involve writers or SAG actors.

Iain Marcks: You’re also a member of the Slovak Association of Cinematographers, the ASK, as well as being ASC of course. How did that come about?

Steve Gainer: I’ve shot quite a bit in Eastern Europe. I love it there. I think of it as my second home. It’s beautiful. Those countries, they’re Serbia, Slovakia, Croatia, they have fantastic deals as far as producers recouping certain amounts of their funding. And they also have really, really talented crews. I mean, I’m just blown away with the crews that are over there. And so I've shot several films over there. And I was asked if I was interested in joining and I said, “Sure why not?” Like I say, I consider that my second home. If I were a younger man, such as yourself, I might even consider moving over there. Because there's so much work, there's so many resources, it's so beautiful. And it also inspires one of my hobbies, which is metal detecting. And since since I was 12 years old, I've spent some of my spare time which of course, we don't have that much as we get older, but in my spare time, and researching historical events and taking metal detectors, which those things have pretty much improved, like digital cameras have, over the past 15 years. But they have improved so much. And I go to places and when I’m in Eastern Europe, when I’m allowed, I go to locations where Romans were, or Celts were, or just medieval people lived and I love finding their coins and buttons and accouterments. So, spent a lot of time, downtime doing that. And when you're in Eastern Europe, you have a couple of choices of things you can do with your time: you can either metal detect or drink rakia. And while I love rakia, I also love finding my way home at night. So I take a lot of my spare time and actually research and go out and find some cool Roman coins and stuff. You know, it's amazing.

Iain Marcks: Sounds like you’re a bit of a history buff.

Steve Gainer: Well, one would think. I mean, I am an authority on the history of cinematography. And I am also a collector of vintage guitars and amps, and a player as well. Here's my theory on all of this: In order to really progress, you have to have a firm understanding of history. You know, I feel like not that many people these days spend any time researching and understanding truly what's going on. In the past, innumerable wars, horrible, horrible situations that human beings have been placed in, under the dictatorship or rule of other people. Very rarely are young people, I think, really investing time and understanding that. And, you know, by not understanding that, you're not preventing that cycle from happening again, you know what I mean?

Iain Marcks: Oh, agreed.

Steve Gainer: And we can talk more about that later. And we can talk about, specifically one camera that you had an interesting question about. Well, we'll get to that.

Iain Marcks: Right, and by putting people in touch literally, with the past, you're able to make it more real.

Steve Gainer: For instance, when I was a child, I went with my family to Washington, DC. And we went to Ford’s Theater, and I saw the gun that Booth used to shoot Lincoln. Now that’s mind-blowing, first of all, that it even exists, but that I was able to put my eyes on that thing. And is that thing necessarily, you know, something that should be celebrated? Of course not. But does it bring it home that this actually happened? And that, you know, here is the device that actually did it? Yeah. And I think it's important for people to see these things like that, because it makes the event real, you know, this happened 160 some odd years ago, how in the world can you connect with that? You can’t necessarily connect with it by reading about it, you know, on Wikipedia, but if you can see, you know, Lincoln's chair, with the bloodstains on it, it becomes an immediate thing, a tactile thing. And one of the reasons that I struggle, and try so hard to preserve the history of the American Society of Cinematographers, is so that the future can see these things and can learn from these things. You know, God only knows what's going to be going on in cinematography in five years, let alone 100 years from now. But in five years, will AI be creating imagery? We don't know. Is it a possibility? Yes. So my job is to keep these things, these Pathé cameras, these Parvo cameras, these Mitchell, Bell & Howells, in pristine condition. Actually, in working condition, so that people can put their hands on them. You know, the ASC Museum, with certain restrictions, has always been a hands-on type of museum. This is not a white glove thing. And most of our cameras are functioning if you have film. So when I’m bringing students through, or when I’m giving a tour to whomever, it's important that they crank the camera. It doesn’t hurt the camera, and the camera loves it, it wants to be cranked. But to turn a camera that was used 100 years ago, 110 years ago, it suddenly makes it real. You know, we’ve all seen the images, the video images of guys cranking cameras, but we haven’t all turned the crank. And to me, it's really important to turn the crank, you know, then you get it. You're there. You're where the cinematographer was, you know, and, and your depth of understanding of the history and the meaning of cinematography is so much deeper. You know, it’s so much more important. That’s, that's my feeling. Anyway, that’s why I do it.

Iain Marcks: How did you become the curator of the ASC Museum?

Steve Gainer: Around 1998, I was shooting, shooting a lot of these things called infomercials. They are rarely seen today. But essentially, it was something that looked like a talk show, but in fact, was an hour long advertisement. You know, a guest would come on to the set and sit with the host and talk about their products. So, it was horrible. But I had to start somewhere. There I was, shooting these things, and I learned that there was this thing online called eBay. And so I started browsing it and I started seeing vintage cameras. Well, that really piqued my interest because I was very much interested in the history of cinematography. And that began by me reading a book by Joseph Walker, ASC, who was Frank Capra’s, cinematographer. The book is called The Light on Her Face. It's a fantastic book, and it inspired me and made me, you know, thrilled about the idea of cinematography. Of course, I was under the impression that cinematographer was setting lights and you know, setting up these incredible dolly moves and making art, when later I would find that probably a good 60 to 75 percent of cinematography is negotiating with producers and trying to get that gear to use and also, you know, just trying to get the gig.

So, I started buying cameras, and I started learning about the vintage gear, and I heard that there was a museum at the ASC for cameras. Now, of course, the ASC Clubhouse was the veritable temple of cinematography still is. And I went to the gate, and I pushed the buzzer and they just opened the gate. And I went inside. And I walked into the building, and it was very dark. And there were a couple of elder statesman members. I won’t mention any names, but they’re gone now. And they were, they were in the back. And I walked in, and I started looking at the cases and one of them said, “Can I help you?” And I said, “Yes, I just came to look at the vintage cameras.” And he goes, “Would you please leave?” So I left. And I was terrified, right? But I came back, you know, I figured he couldn't be there all the time. And I came back, and I came back, and I came back. And one time that I was visiting, the person who was in charge, kind of the caretaker of the building and the lawns, Benny [Toguchi], was walking past and he had a vintage lens in his hands. And he's talking to someone, he goes, “I don't know where it goes. I don't even know what camera it’s for.” And I looked, and I said, “Oh, that's a lens for the Technicolor camera.” And he goes, “How do you know that?” I go, “Well, I collect old cameras. And by the way, who's in charge of this collection?” And he goes, “That's the problem. No one is in charge of the collection.” And I said, “Wow, well, who would one speak to to find out about and getting that gig?” And he said, “Victor.” and I said, “Victor?” He goes, “Yeah, Victor Kemper.” And I go, “Victor Kemper?” And somebody behind me said, “Yes?” And I turned around, and it was Victor Kemper!

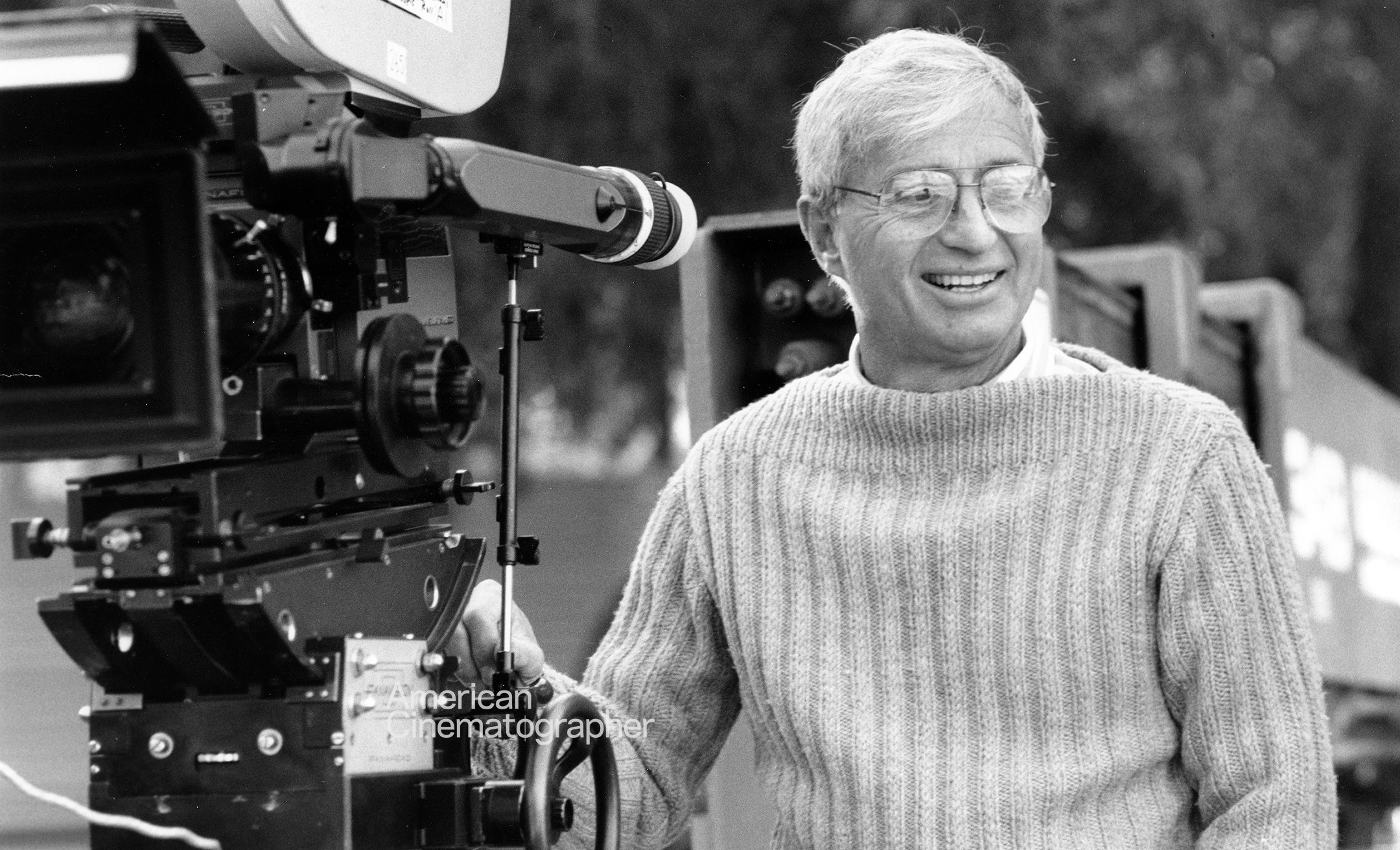

Now, Victor Kemper, who recently passed away, was an incredible cinematographer. His body of work is maddening, because he goes so far as from, you know, Dog Day Afternoon to Pee Wee's Big Adventure and so many great films. He worked, you know, all the time throughout his career. So I was in awe to meet Victor Kemper. I knew who he was. And he looked at me and he goes, “Hey, have a seat. I’ve got a meeting that I'm doing. And I'll come out and talk to you.” So I sat down, it was probably about 10am. He came back out at 5pm. And I was still sitting there and he goes, “You're still here?” I said, “Yep.” So he said, “All right, come in my office.”

So I sold him my bill of goods. I told him I was a collector. At that time, I was working at Paramount Pictures in the laboratory. And I knew quite a few members of the ASC from Paramount Pictures. So he goes "Well, I'll bring this up to the next board meeting." And luckily, many of those board members were cinematographers that I'd met at Paramount, so they had a trust in me from running the lab. And I was made the curator of the ASC’s camera collection. This was a long time ago, and I was, you know, overwhelmed. And on pins and needles. So I think it was probably about four months later that he called me and said "You're in," and I began the process, first of inventorying what was visible. And I did that for many months. And at that period of my life, I was shooting a ton of music videos, which meant that I made enough money that I didn't work all the time I worked, you know, a couple of days a week or one whole week, and then it was off for a week. So I had a lot of free time. And I spent that free time inventorying and organizing the collection to the point where I was convinced that I had it set up, and then old Ben Toguchi once again came to me and goes, “Hey, can I get you to help me with something?” And I said, “Sure.”

So he led me outside of the building and around back and there was a wrought iron gate on the bottom of the building. He unlocked it and opened it up. And he goes, “Look in there.” And it was like Raiders of the Lost Ark or something. There's cobwebs and dust. And there was a vent that sunlight was coming through and making a ray of light. And I couldn't believe what I saw. I saw dozens of vintage motion picture cameras sitting on the dirt underneath the ASC Clubhouse. Just sitting there. And I was like, “Oh my God.” You know, first of all, my first thought was, Where the hell am I going to put all this stuff? The second thought was, "Oh, my God, you got, you know, wooden leather covered Pathé cameras sitting on the dirt." So I was terrified that you know, termites, we have a lot of termites here in California, terrified that the termites may have had their way with the cameras. But unbelievably, because of the arid conditions that we had at that time, none of them were damaged. And it just all required a good dusting and cleaning up and maybe a little bit of Mitchell camera oil to get them running again. So, in a nutshell, that is the story of how I came to be the curator of the ASC’s camera collection.

Iain Marcks: Now at that time, what was the purpose of the collection, such as it was?

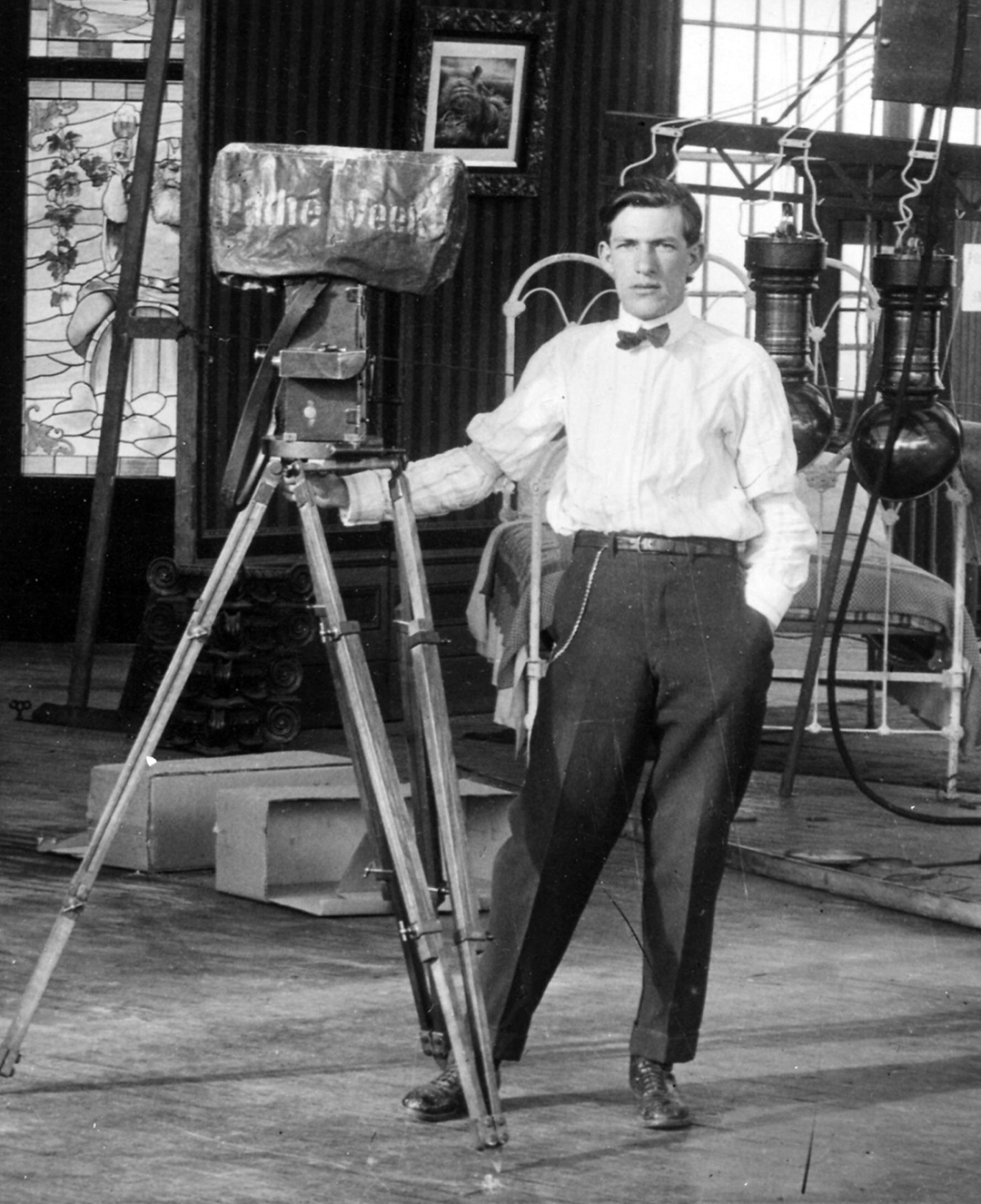

Steve Gainer: The collection began under the auspices of Arthur Miller, ASC and he started it with one of his Pathé cameras. And we now have two of his Pathé cameras, but he started with one of his Pathé cameras, and the idea I believe, much as it is today, was to build the legacy for the members of the ASC of the vintage camera gear, and you know, what I really like doing — and I think this was Arthur’s goal too; at least, I like to think it is — is provenance. To be able to say this camera was used by Gregg Toland [ASC] on Citizen Kane. That’s powerful, man. The collection that we have, most of it has provenance. And we’re able to say that, you know, it was used by this cinematographer and donated by this cinematographer, which is how by the way we get the majority of our collection, is donations, either directly from the cinematographer, or from his family. And, you know, we're a nonprofit org. So we're able to give tax certificates to the people who make those donations. So they're not really just giving it away, they get something back in kind.

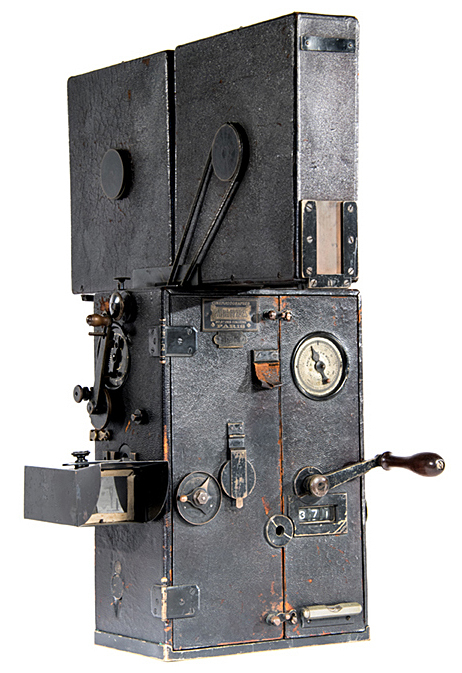

But first, Arthur Miller. And Charles Clark [ASC] actually really built the collection up, he is responsible for one of our most valuable pieces, which is our original Edison Kinetoscope. There are six of those known in the world. And we have one. Now, he also gave one to the Academy. And that is actually at the Margaret Herrick Library right now, if anyone goes there, they can see that one there, but we have one, they have one, and then there are four more that are spread around the world. So the original Kinetoscope, in case, no one knows what that is, was what Edison initially was showing his motion pictures on. He wasn't projecting originally, he was using a Kinetoscope, which is a box that has a loop of film and a light. And you can look inside, and you can watch that loop film play after you paid. Edison specifically wanted to be paid, as do we all.

Iain Marcks: Sure, you gotta get that nickel.

Steve Gainer: A nickel particularly because, you know, you do know that those theaters were called nickelodeons, and that's where that term comes from. So you know, of course the Lumière brothers in France began projecting and shortly thereafter, Edison worked with his engineers, notably W.K.L. Dickson, in order to begin projecting in the United States, whereupon the early movie theaters, a really popular one, one in particular that the Warner Brothers used, were funeral homes, they already had the chairs.

Iain Marcks: The Kinetoscope, is that still in working condition?

Steve Gainer: Absolutely. You know, I would say 80 to 90 percent of our collection is in working condition. Some things are just broken. And they're kept broken, because they were broken while in use. Other things are impossible to replace certain pieces without it being too obvious, and, you know, look like a forgery. But the majority of the cameras have been cranked or plugged in. Because we do have cameras, many cameras that were used after the hand crank era, you know, we have all the way up into modern cameras. We have a prototype of the Red camera, the Red One, we have a Panavision Genesis camera, we have an Arri Alexa, you know, we have we have the earlier cameras in the digital age all the way back to the very beginning, we have a Lumière camera, a very early one with around perforations, not the Edison perfs. But again, you know, provenance makes the world go around when we're talking about collecting. And that's been my goal, from the very beginning was to make certain that the names of the cinematographers and the films were associated with the pieces that we have.

Iain Marcks: What kinds of objects are there in the collection, other than the ones that we've talked about?

Steve Gainer: Well, we do have a small collection of projectors, though, that's really not what we're about. The cinematographer ordinarily wouldn't have that much to do with a projector. That's something that was post, basically. But we do have a large collection of cinematographers’ personal possessions, like light meters and viewing filters, and, you know, just the stuff of an everyday cinematographer. And those things changed over the years. You know, initially, cinematographers would carry, you know, paint brushes and nets that they would burn with cigarettes to burn holes in so that certain areas weren't diffused with the net, and net frames and scissors. You know, you wouldn't think of a cinematographer necessarily today valuing a pair of scissors in his kit. But in the early days, that was a very valuable tool, you know, because you were cutting mattes or nets or whatever you might need to work on your camera. A lot of things. You couldn't call Panavision, or Otto Nemenz or Keslow, and have a tech drop by set real quick. If you were out in the desert with a couple of Bell & Howell 2709s shooting, you had to know how to fix the things yourself.

For instance, I recently took in a donation of the great Elmer Dyer, ASC’s possessions. And he had all sorts of tools in his kit, because, you know, he was an aerial cinematographer. That's probably what he's the most famous for is his aerial work. He had to mount the things, you know, the grip crews back in that silent area, were not the same as they are today. Today, the grips take care of a lot of the mechanical stuff that has to happen on set. But back then, the cinematographer was pretty much on his own and had to figure out rigging and such and you know, rigging a camera into a biplane that's going to be upside down is a challenge, I would have to assume. I've never done it myself. But Elmer did it a lot. And so, you know, his ditty bag that was part of that collection, and had all sorts of tools in it. And it was, you know, kind of it was very entertaining and somewhat astonishing to see what you dragged around then.

Iain Marcks: One of the most striking things about the collection is the amount of handmade objects. One of my favorite pieces was this tin viewfinder, it was just like a thin, flat piece of metal that had been hammered into the shape of a director's viewfinder. Do you remember whose that was?

Steve Gainer: You know, I'm uncertain because that is one of the very few pieces that is in the collection that I don't think has direct provenance with the cinematographer. But it is on display in the boardroom right now. I know exactly where it is. And I know exactly what you're talking about. But we have lots of other viewfinders. You know, there was a trend back then for some photographers to put their names on their personal things with a letter punch. And so all of their viewing glasses and their little viewfinders have their names on it. And there's some very interesting pieces in there. And we do have, I would say, in the collection, probably 20 to 30 of those little viewfinders that are directly linked to cinematographers from the early days. So that's really cool.

One of my favorite handmade things is, you know, Gregg Toland, ASC was an inventor, he was clearly an innovator, in many, many ways. And on the camera that we have on display, which is [Mitchell] BNC #2, that he used for Citizen Kane. And he also used it for The Grapes of Wrath, among other films, there were several little things that he did to the camera, you know. You know, a Mitchell viewfinder, what that it looks like, he built a little eyebrow for it. No one else, apparently, until that time had even thought of anything like that, you know, as a trend back in that day, because they were working with so many hard lights, for the operator and the cinematographer and the gaffer to all have, like duckbills on, you know, so that they could get the light out of their eyes in order to see what's going on, like, like you do in a matte box, like the eyebrow on a matte box. So he had the wherewithal to think of, well, here's the viewfinder and you know, you're kind of putting your eyes up here, why not have a little piece of sheet metal that's coming up to keep the light out of your eyes. So I look at that, and I'm like, It's so simple. But this thing didn't occur until you know, 1936 or '37.

Iain Marcks: Right? It's like a cutter for your eyes.

Steve Gainer: That's all it is. But clearly, no one had thought of it until that point. And after that, then of course, lots of people had it. So he innovated a jillion things like that. If you research the archive of American Cinematographer, you can find several articles where he talks about his innovations. And I encourage people to do that.

Iain Marcks: That’s so cool. And it's a good reminder that innovation doesn't always have to come in the form of some grand technical achievement.

Steve Gainer: That's it, man. You know, the simple things are the important things, right?

Iain Marcks: That's right. Now I understand you've started working recently with Richard Edlund, ASC to co-curate the collection. How did he come to be involved? And what's he working on?

Steve Gainer: Well, this was entirely my doing. There's another person that helps me a lot. He's a director by the name of Mark Kirkland. He's Douglas Kirkland’s son, the great still photographer. Mark is a big camera collector, and is a friend of the ASC and is a kind of part-time co-curator but Richard Edlund... First of all, let's just talk about Richard Edlund, okay?

Richard Edlund is unquestionably a genius. He is a living genius. He is living and breathing, and I'm happy to say, my friend and he knows so much about motion picture cameras. He's forgotten more than I'll ever know. That's the old saying, right? Also, Richard Edlund ASC invented the Pignose guitar amplifier as used by Jimi Hendrix, Jimmy Page, all of the greats. Eric Clapton. This guy invented the first portable guitar amp. Brilliant! Okay, so he did that. He also, by the way, won three Academy Awards, you know, just something beside there.

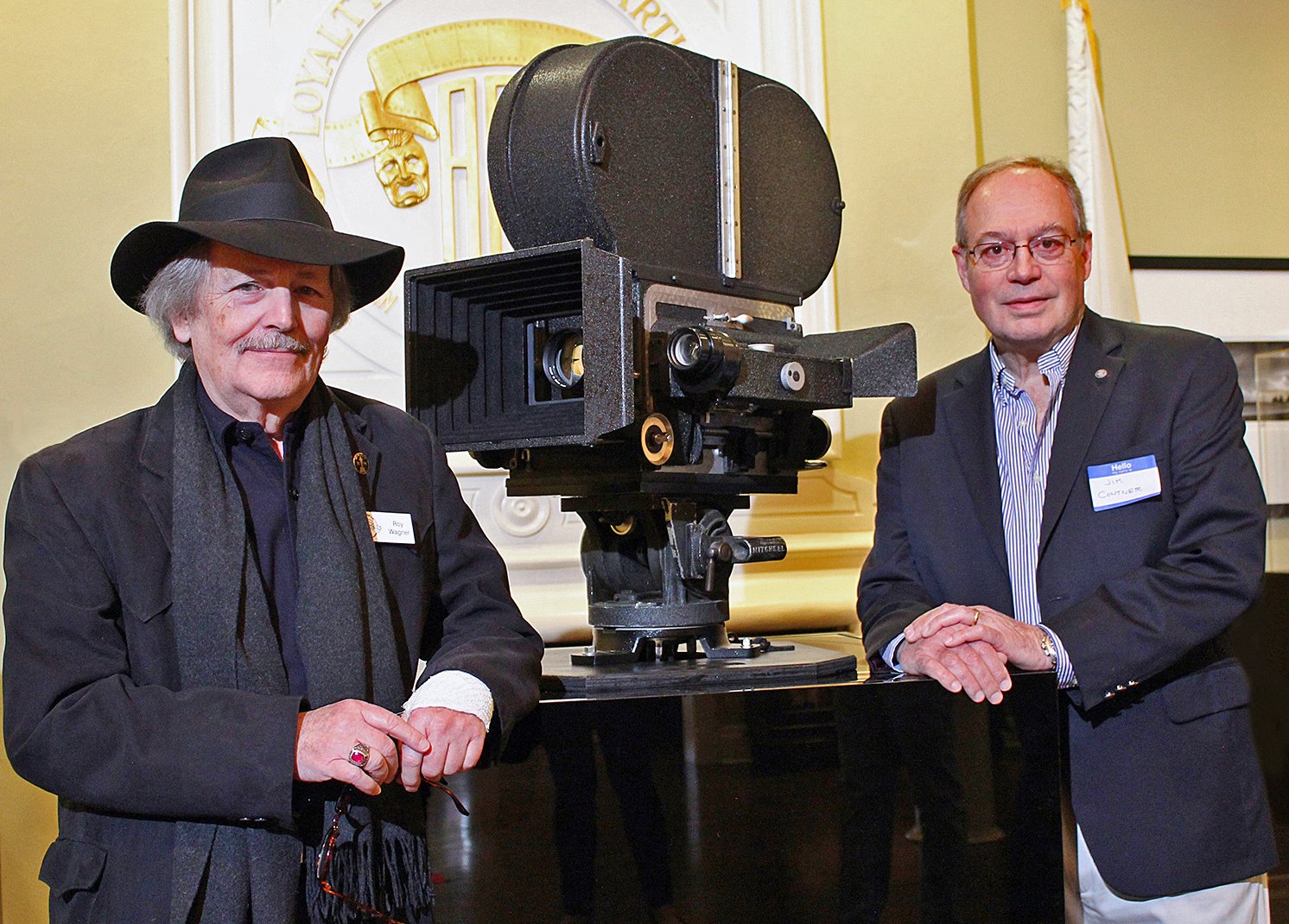

But Richard and I are friends and I've spent a lot of time with him recently, and I spent time ogling over his collection, which is lovely. Some of it’s on display at the ASC currently, including Warner Bros. very first camera they bought in 1918, in November 1918, from Bell & Howell, the 2709. And it's gorgeous. And because he is such a powerful force, for cinematography, for the history of cinematography, for history in general, I felt that it was time to bring someone like that in, and I couldn't be more proud or honored to have Richard as a co-curator of the collection with me.

It's nice to have other people who know a lot about the collection and about the history of the cameras to populate the building. And, you know, to tell people about it. That's what we're really focusing on right now. I've been working a lot with David Williams, at American Cinematographer, and with the [ASC] website and all of that, doing these little videos called the Museum Minute. And in the Museum Minute, I talk about a specific camera, show how it's threaded, and we talk about the various functions of the camera. And those are on the website. And what we're doing is creating QR codes for each camera and each thing that's in the museum. And when people go there in the future, they'll be able to train their phone or Apple glasses or god knows what in the in the future at the QR code, and the video will come up and my goofy face will pop up and say, “This is the Mitchell Standard camera that was used by Mary Pickford, and Charles Rosher, ASC, actually hand cranked this camera shooting Mary Pickford films, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. So I'm thrilled that now there's going to be a historical record that's easily accessible by visitors, and doesn't necessarily require me to be there or Richard to be there. But I have to say, my happiest times are when we're both there.

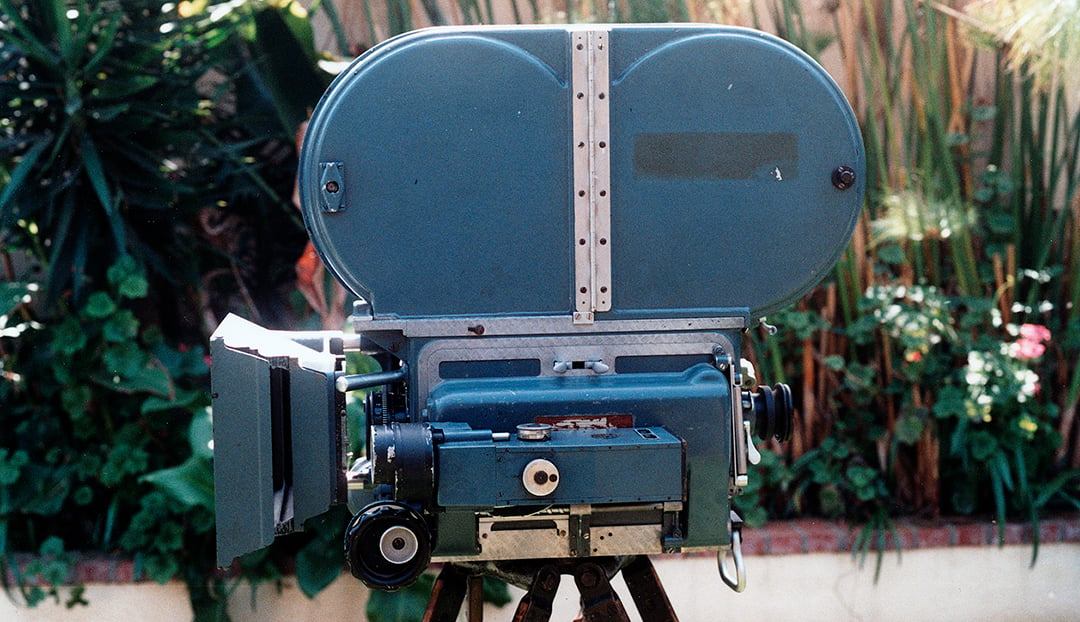

Iain Marcks: Let’s talk about some of the crown jewels of the collection. We've already mentioned two cameras in passing, the first one being Gregg Toland, ASC’s Mitchell BNC #2, which we know was used to shoot films like Citizen Kane and The Grapes of Wrath. How would you describe this camera, for those who aren't familiar with Mitchell cameras?

Steve Gainer: Well, the Mitchell BNC camera is a relatively large, quite heavy motion-picture camera. If you think of, you know what most people think of an old time movie camera with the Mickey Mouse ears magazine, it's that camera housed inside of a metal and composite blimp so that it's quiet so that you can shoot sound with it. Because you know, the early cameras that were during the quote-unquote Silent Era made a lot of racket, and it didn't matter. But when sound became a thing, they shoved cinematographers first into a booth, and then shortly after that, cinematographers began demanding that, you know, some sort of silencing blimp be manufactured for the camera. Ultimately, the Mitchell camera came along and made their own BNC: blimped noiseless camera.

That camera, which like I said, weighs quite a lot. [Camera] #1 was a prototype, and #2 was purchased by Samuel Goldwyn. Now, Samuel Goldwyn was a mentor for Gregg Toland ASC, who began his career as a camera assistant for Sam Goldwyn. And I actually have in my own personal collection, a bunch of Greg's contracts with Sam Goldwyn. And he actually was in the beginning working for $75 a week, and at some point, graduated to $150 a week as a camera assistant. And then, you know, of course made more, but not that much more, you'd be shocked. Of course, that amount of money back in the 20s was quite a bit more than it is today. So when I became the curator, I made it a point, I said, There are two cameras that I must find for this collection. One, the camera used to shoot Citizen Kane, because it is arguably one of the most famous and revered motion pictures ever. And two: the camera that Billy Bitzer used with D.W. Griffith. The Toland camera was a lot easier. I asked around, all the aged members of the ASC at our monthly meetings, and finally ran into a guy named Sol Negrin [ASC], who was a lovely man and actually was one of the people who voted me into the ASC as member. Sol Negrin had used the camera when he was shooting the television show Kojak.

Iain Marcks: That's my grandma's favorite show.

Steve Gainer: Right? So he had used the camera and he knew that there was a gentleman by the name of Burgi Contner [ASC], who owns that camera. So I had that information. Well, I started asking around about Burgi Contner, and another of our members, a good friend of mine, Roy Wagner, ASC, who was also one of the people who voted me into the ASC as a member. And he said, “Hey, I know Jimmy Contner, Burgi’s son. He's a director/cinematographer. So we reached out via Roy to Jimmy Contner, and the camera indeed was still in their possession and was in storage doing nothing. We suggested that it be put on display at the ASC, to which he agreed, and then sometime later, actually turned his initial loan into a donation to the ASC.

So I got the camera, had it here. This at one time was not a guitar studio, but it was a machine shop for me. And I had a vertical mill and a lathe and all sorts of things that could rip your fingers and other digits off. So ultimately, I got rid of that, brought the camera here. And it'd been utilized as a rental camera and had been painted blue. It had the original Mitchell black crinkle finish taken away and a blue like epoxy type of a finish, kind of a bowling ball type finish had been put on it. So I removed that finish. Then I took the camera to Ken Stone, from Stone Cinema Engineering, in Pine Mountain, California, and said “Ken, I need you to un-reflex this camera.” The camera somewhere, probably in the late 60s had been reflexed. You know, the early cameras, you didn't look through the cameras like in a modern day camera, you look through, you can see the image you're shooting. It wasn't that way. You could maybe look through and focus and frame, but then you had to move that tube out of the way and put the film in front of the lens. And so you would look in a parallax viewfinder on the side.

But this camera had been reflexed, meaning that it had had a pellicle prism placed inside of it. So that when the film was exposed, it was blocked. But then as the shutter came around, it would open and you could see through that prism, through the lens. And that was not original. So Ken Stone removed that. And he is such a mechanical genius, he made it so that you can't tell that it was ever that way. And then came the great challenge of finding black crinkle paint, which had been outlawed in the United States, because it seems that it was a carcinogen. It's a different story for a different day, but I definitely did some covert work with the camera in the trunk of my car and me crossing borders in order to make that finish happen. So then that camera came and is now hopefully now and forever on display at the clubhouse.

And as I said, the second camera that I was looking for, of course, would have been a Pathé camera that Billy Bitzer had used with D.W. Griffith.

Iain Marcks: Before we go on to that, when you embarked on this journey of looking for these two cameras, how sure were you of their actual existence?

Steve Gainer: I wasn't. There was no guarantee that I was going to find these things. It's just that I was realizing, you know, cameras aren't like a broken dish that you immediately kind of toss into the trash. Well, I mean, some people probably try and glue them back together, but the majority of them are thrown into the trash. Cameras aren't that way, you know, because they hold a certain intrinsic value. And I had a suspicion that these things existed, especially since I realized after viewing the collection of the ASC that there were many, many cameras that existed I had no idea still existed. Lots of 'em.

Iain Marcks: Like, for instance?

Steve Gainer: In our collection, we have a Hahn Goerz camera, which is an incredibly rare German hand-crank camera, we have a Russell camera, which is a Bakelite bodied hand-crank camera that's incredibly elusive.

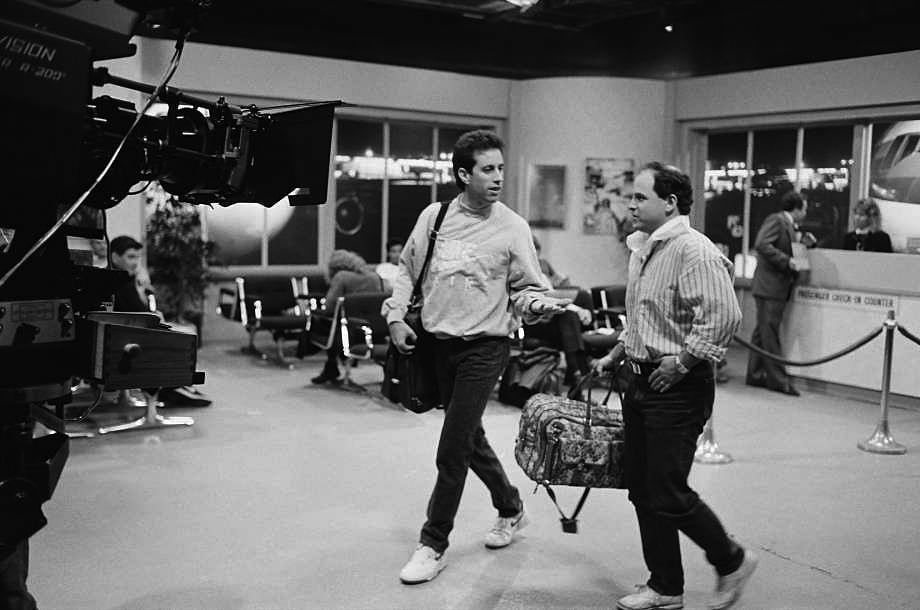

We have many, many things that are just, you know, unusual, aside from the regular cameras that you see out there like Mitchells and Bell & Howells, and you know, there are a lot of Pathé cameras out there, and a lot of Debrie Parvos. I mean, go on eBay, and you will find a Debrie Parvo, they're always for sale for three or four grand, but I just had a feeling especially with the Toland camera, because it was a Mitchell BNC, and we weren't that far away from those cameras still being used. I mean, when I worked at the Paramount lab in the ’90s, they were still using those cameras to shoot the multi-camera TV shows. So they still existed. So it was simply a matter of putting the pieces together and not alerting a lot of people to their existence, because clearly, there are lots of other people out there that would love to get their mitts on those cameras.

I didn't want those cameras clearly for personal gain. I wanted them to go into the museum to be seen by cinematographers and up and coming cinematographers for learning purposes. You know this, this is what we do. When we look at these old things we learn. We learn about the past, we hear the stories about the past, and build a comprehension of what it was to make films then versus what it is to shoot films now.

Iain Marcks: It's really amazing how the Mitchell camera was an industry standard almost 100 years ago, and the design of it was robust enough to be converted for an entirely new era of filmmaking, even up until the turn of the century.

Steve Gainer: It’s still in use because the guts of the Panavision film cameras, you know, the Gold II or the Platinum, those cameras, if you open them are basically identical to Mitchell, they have the same type of movement. They might have an extra, you know, pulley or something in there for the film to roll on to make them a little bit quieter. But if you look at the movements between Mitchell NC or BNC cameras, and the Panavision Platinum camera, they're essentially identical.

Iain Marcks: And because Panavision started out primarily as a lens company, if you wanted to use a Panavision lens, you were putting it on a Mitchell camera with a Panavision mount.

Steve Gainer: That is correct.

Iain Marcks: And I'm sure someone there at some point was — was it like the 1960s? I was looking up information on the Panavision R-200 — sometime in the 1960s, they just decided to grab those guts and make their own camera, which is amazing. You know, like Wayne Kennan, ASC used it to shoot Seinfeld in the 1990s.

Steve Gainer: I know. Well, those cameras, you know, the Super 200s, they look like a Mitchell BNC because they are. They refined it of course. Panavision, if nothing else, has always been fantastic at refining the tools that we use as cinematographers. You know, the lenses, the cameras, the gear heads, you know, they really, really, really made life easier and more effective, more productive for cinematographers in their designs. I hope I don't take anything away from the great glory that is Panavision by saying that, basically they used a Mitchell camera, but they were wise enough to know that this design was practically as good as it could possibly be with the exception of making it a little more noiseless and maybe improving upon the gearing and giving the cameras more versatility, more options.

You know, you can't handhold a BNC camera, but you can handhold a Panavision Gold II. It's not that comfortable, but you can, because it's still a pretty heavy damn camera, but you're no longer having to use an Eyemo as a handheld camera or an Arri IIC, both of which are fine cameras but don't offer the options that the Panavision Gold II would have offered, you know, an operator. And you know, the viewing systems in the Panavision cameras are probably the greatest achievement, they really improve the viewing in those cameras, well over the pellicle situation in the reflexed Mitchell cameras. Even in just the viewing tubes, you know, you have several sizes of viewing tubes, you have a handheld with a little short guy, you have the big one that you're going to use on the dolly that has the eyepiece leveler adjustment, which, those are great achievements. And I think they won a bunch of Academy Awards over the years for their scientific achievements, because they did great things. But yeah, that camera exists today as one of the greatest achievements in motion picture cameras, the other of course, being the Arriflex cameras, which are also extraordinary in their own right,

Iain Marcks: Right, I think the last 35 millimeter Arriflex camera to be produced was the 435 Extreme, which came out in 2004.

Steve Gainer: I used the 435 a ton on music videos. You know, that's an MOS camera. But before that we were using the BLs you know, the BL and then the 535 was a redesign entirely, you know, a beautiful camera, such a gorgeous camera.

Iain Marcks: It's hard to imagine 35 millimeter cameras getting any better, not to compare Panavision to Arri, but just the basics of 35 millimeter camera technology, unlike digital camera technology now where you know, a newer, quote-unquote better camera comes out practically every year. But it makes me wonder if maybe this is what it was like 100 years ago, when cinematography itself was still in its infancy.

Steve Gainer: The biggest breakthroughs were from the Lumière camera, which had a 50 foot magazine, that was also an optical printer and a projector all in one to the Pathé camera, which had a 300 meter magazine, let's call it 400 feet, but a 300 meter magazine and you know, a footage counter and an adjustable shutter, and things started appearing in front of the cameras like vignetting irises and all of that, to the Bell & Howell 2709, which was a metal body camera with absolute precision, which had registration pins that were built into the movement. And the film was literally pushed onto the pins. So there was zero tolerance, there's absolutely no way that the film is going to move in the gate once it's there.

And then from the Bell & Howell 2709 to the Mitchell camera which, its greatest innovation was the rack over viewing system. You didn’t have to, as with the Bell & Howell camera, in order to change lenses, you did have a turret on the front, you could turn the lens, but then you had to move the camera over on a dovetail where you had to push the matte box out, move the camera, turn the turret, look through the viewfinder focus and set your frame. And then you had to do that in reverse, you had to slide the camera over, turn the turret back so that the lens was in front of the film, and pull the matte box back. Whereas with the Mitchell camera, all you had to do was rack over the camera body. So that's a gigantic innovation. It saved a jillion hours of shooting time and actually probably saved 100,000 cinematographers’ jobs because they didn't forget to push the matte box back in, which happened a lot with a 2709. According to some of the things that I've read, a lot of shots were ruined because as they're doing the 2709 process, and they're in a hurry, and the director is going, “let's go, let's go, let's go,” they would forget the last step, which is to slide the matte box back in, you're not looking through the camera, grab the shot, and then look and go, “Oh my god, the matte box is out there.” It's in the shot. So that happened.

But you know, these innovations happen. You know, to your point, your earlier point, film camera innovations are probably over, as far as 35 millimeter goes, mostly because of economics. I mean, there just aren't that many shows that are driving the process. You know, there aren't that many people shooting 35 millimeter film that they're like, “Wow, we need to reinvent this incredible Panavision or Arriflex camera.” It's just not a fact anymore. If that were the only business in town, I dare say they probably would have made some more achievements. Maybe with the newer materials that exist today, carbon fiber and they would have been able to make lighter cameras, perhaps certainly, you know, the video taps would have all been maybe 4K video taps. Who knows? But as it stands, I don't think they're really going to spend a great deal of engineering and money and R&D into redesigning those cameras when they work fantastic. And it's not like the film stock itself is changing in such a way that it requires those movements to be altered or redesigned. And I will say this, I recently taught an ASC masterclass on film, and I shot with some hand crank cameras. I shot with our Mitchell camera and I shot with a Pathé camera. And I'm happy to report that those images are just as gorgeous and stunning as ever, you know, they were really really fascinating. To see something shot with the Pathé camera projected onto a big screen now, it was kind of mind blowing.

Iain Marcks: Speaking of which, the one you really wanted for this collection was Billy Blitzer's 1911 Pathé studio camera. What makes it so special?

Steve Gainer: Right? Well, you know, I am a historian, and I believe in preserving history. And it is a fact that D.W. Griffith changed filmmaking entirely. Before him, they were cranking out one-reelers at best, you know. And before him, many of the innovations that he and Bitzer utilized, maybe had been tried but hadn't been perfected, you know. So certain things like in Intolerance specifically. In Intolerance, the giant dolly booming shot, people have never seen anything like that before. You know, the camera starts well up over the set. And as it pushes in and gradually drops — that was mind-bending for people in the theaters. You know, before Griffith came along, people couldn't even understand really how medium shot existed because, where's the person's legs? Griffith brought all of these innovations into the cinema dialog. He made these things everyday. Now, while some of his choices of subject matter, most specifically The Clansman, which was a racist, awful book that he renamed The Birth of a Nation, a pretty darn horrible topic for a film, let's be honest. That being said, we can't ignore the innovations that he created. We can damn him for his content, but let's not damn the process. Now. While Bitzer’s camera may have shot what was unquestionably a racist topic film, it also shot dozens of other films, you know, before Karl Struss [ASC] and other cinematographers took over Bitzer with Griffith. That camera was used, I mean, it did work on Intolerance, it did work on Broken Blossoms, it did work on Way Down East, right? It did work on all these other films. So I felt that because it had helped innovate so many things in the history of cinema, that it was a valuable piece and deserved to be on display.

Iain Marcks: You said you wanted people to be able to learn from the ASC’s camera collection. But, what has curating it taught you about the art and craft of cinematography?

Steve Gainer: So very, very much. I'm really, really fortunate that I've been able to spend the time that I have with the collection, and not only with the collection, but with so many members of the ASC because I'm there quite a lot. Being around all of those people, obviously, you know, it's like osmosis, you just you soak it in. I've had conversations with cinematographers over these many long years now, like Conrad Hall [ASC], what a treasure, like Vilmos Zsigmond, [ASC, HSC]. These people like Vittorio Storaro [ASC, AIC], these people I've sat with, and I've had conversations, and we've talked cinematography, and at the same time, we've talked the history of cinema, and I've been able to show them things in the collection. And they've had recollections of all you know, “I know about this thing.”

And this was used in such and such a way, in that regard, I have learned a great deal, but simply in understanding the mechanics of the mechanisms, not to be redundant, themselves. Just understanding and looking at progress, and how things evolved. You know, the evolution of cinematography is kind of stunning, because we went from it not being anything at all, not existing, to people being entertained by it, and in a short manner of time. And so much so that it became a multi billion dollar business, who knows, after 100 years, a trillion dollar business that it's been, and is still here, you know, we're still out there telling stories. So to me getting to spend my spare time, it's not just about having the old cameras and cranking the old cameras and hanging out with them and all that, it's about respecting the art and craft of cinematography, and how it's changed. And it's kind of afforded me a set of goggles to look at how it's currently changing, how it has changed so much over the past few years.

One could say that at the birth of HD, the images weren't necessarily super great. They kind of sucked. But at a certain point, we as cinematographers were very often required to use these cameras, because the budget suddenly couldn't support the use of film. We can't, you know, processing and telecine. They're telling us “No, you can't do that anymore. It's too expensive.” Well, gee, six months ago it was no problem, you know, but now it is.

Well, cinema is changing again. And even as we speak, it's changing. And it's very exciting to view all of this. I guess I'm a fortunate person in the time that I was born, because I'm able to have worked in film, worked in HD, you know, I've been able to utilize all these tools. I had the hot lights. Now I've got LEDs, right. I had to use process trailers, and now I have volume walls. And all in the same career. That's kind of crazy. You know, when you think about it, if you're a baker, and you make bread, you're probably using basically the same techniques that were used 2000 years ago, right? So that hasn't evolved in the same way that cinematography has. And that's an important thing to keep in mind. It's important also to look forward and say, Where are we headed, and I'm gonna leave that to everyone else's point of view. But I think there are some strong indicators of where cinematography may be headed in the short term and the long term. And I think it's important for people, just like we've evolved over the past, to pay attention and look at what's about to happen, and be a part of it. Don't be a victim of it.

Iain Marcks: Right, it's like to know where you're going, you have to remember where you've been.

Steve Gainer: It’s important to look at those changes that have happened over the evolution of cinema. You know, if I'd been a guy, if I'd been a guy that said, Well, you know, sound, “I'm not ever doing sound, it's never gonna happen,” right? Or “I'm not gonna shoot color, the color is not gonna be great,” right? Or “I'm not gonna shoot in HD, it's never...” Well, at each of those times, you have to evolve and you have to roll with it. You know, if you're going to be successful in this industry, you have to be willing to take a chance and stick your neck out.

There was a time when someone would say, Okay, do you want Panavision or Arri? Do you want Zeiss or Cooke? Do you want Kodak or Fuji? And then one day, and I remember this very clearly, this one day, the producer said, “Okay, so you're shooting on the Red One.” And I was like, “I am?” And there was no book, you know, no great resource to immediately absorb all the information in the world about a Red camera in order to make it perfect. It was something that I learned as I evolved, and I had to take a chance. And, you know, this is something — luckily, I'd spent time in post situations where I understood what a waveform was, you know, and, and a vectorscope, for that matter. And so having spent that time in there, I knew, luckily, where my exposure probably should be, in order to have adequate exposure for whatever the final product was going to look like, which I had no idea because I'd never used it. And at that, in the very beginning, there was no DIT, you know, no one to say, “I think you're a little thin, you might want to open up a third,” you know, none of that. Just, oh my, I'm shooting with this new whole new system. And I feel like in my heart of hearts, that we're approaching a similar time.

And again, everyone else can build their own opinions about what's going to happen in the future. But I will say this, if there's anything that you can learn over time, in both cinematography, and just the general history of film is that expense will drive what the final product is, budget will drive that if people are able to discover less expensive ways to end up with a similar product — don't wanna say better, necessarily, but a similar product — they probably will do that.

Iain Marcks: Other than the clubhouse in Hollywood, is there any place people can go, where they can see pieces from the ASCs museum collection?

Steve Gainer: Currently, at this very moment, we have Billy Fraker [ASC]'s Arri IIB camera that he used on Bullitt. And they have a display in the Transportation Museum at the Smithsonian of cars from the movies. And they have the Mustang that was used in Bullitt. And Billy Fraker, ASC’s Arri IIC is at the car currently, and will be there for the next eight years. I think it's wonderful to be able to, you know, its provenance, right? It's able to reconnect those things, the car and the camera, because they made some compelling images going over the streets in San Francisco with that car and fantastic shots. And Fraker was, you know, kind of a pioneer in that sort of stuff.

And there is a display at the Academy Museum currently and for the next year of The Godfather, and I helped the folks at the Academy Museum curate the camera aspect of that collection, we got the proper Mitchell BNC camera with the proper Worrell gear head with the proper dolly, so that it looks exactly like the camera system [Gordon Willis, ASC] used on The Godfather. Whether or not that's the exact camera, we can't be for sure, because we haven't been able to locate the camera reports. But there aren't that many CSC BNCR cameras that exist, so the odds are good that it is actually the actual camera that worked on The Godfather. We can't be sure about it.

Iain Marcks: All right. So for now, if you want to see most of these pieces, you have to go to the clubhouse, but you can't just walk in and start cranking the camera.

Steve Gainer: You need to contact me if you really want to get the nickel tour. There have been people who've managed to get in and look around, but you don't get the stories and you don't get to turn the crank. But you know, for everyone out there, if you want to go to the ASC website and dig around, you'll find those Museum Minutes and you know, if you do happen to find yourself in Hollywood, and I don't happen to be working on a film or television series, I'd be more than happy to show you around. Come in, check things out. It's a great place to learn. And it's also, you know, just a fulfilling place to be because it is the temple of cinematography. There's nothing like walking through those doors realizing that all of the greats have walked through those doors at one time or another.

Iain Marcks: Year after year, that feeling never goes away.

Steve Gainer: We can now say basically century after century at this point, you know?

Additional episodes of the ASC Museum Minute are currently in postproduction.

American Cinematographer interviews cinematographers, directors and other filmmakers to take you behind the scenes on major studio movies, independent films and popular television series.

Subscribe on iTunes