Let Me In is a Bloody Valentine

A young boy falls for a vampire in this moody and macabre horror drama, shot by Greig Fraser and directed by Matt Reeves.

This article originally appeared in AC, Oct. 2010.

Reimagining the acclaimed Swedish vampire drama Let the Right One In for American audiences, the new film Let Me In follows 12-year-olds Owen (Kodi Smit-McPhee) and Abby (Chloë Grace Moretz), whose burgeoning romance is complicated by the fact that he is human and she isn’t. In his search for a cinematographer, director Matt Reeves wanted “someone who could find beauty in the real,” and after seeing Jane Campion’s Bright Star (AC Oct. ’09), he sent the script to cinematographer Greig Fraser. “There’s a very natural, poetic feel to Greig’s work,” says Reeves. “All of my instincts about this film were borne out and exceeded when I met him.”

When he received the script, Fraser knew of the Swedish film (directed by Tomas Alfredson and shot by Hoyte Van Hoytema, FSF, NSC), but hadn’t seen it. “I loved the script, and from that point on, I knew I couldn’t see the original until I finished our film,” he says. “Matt encouraged everyone else on the crew who hadn’t seen it not to watch it, because he wanted all of us to bring our own take on the story.”

During prep, Reeves and Fraser studied Rear Window, The Shining and The Exorcist to develop ideas about how to create a pervasive sense of dread. “When I say we watched The Shining, I mean we really watched The Shining," says Fraser. “From the word go, you just know that something terrible is going to happen in that film.” Reeves adds, “We used a sort of classical, almost Hitchcockian style to immerse the audience in Owen’s point-of-view, or occasionally another character’s point-of-view; throughout the film, you see what Owen sees married with close shots of him watching. But at certain moments, we juxtaposed that with shots that were more distant to create a feel of inexorable dread, and that was the Kubrick influence.”

Let Me In opens with a shot reminiscent of the opening of The Shining, a wide aerial shot of a snowy mountain road at night. An ambulance and police escort appear from around a bend in the road, near the center of the frame, and the camera begins a slow push in, but not on the vehicles. “It zooms straight forward without a pan or a tilt,” details Fraser. “Throughout the film, we tried to use a few of those uninflected zooms to comment on the mood of a scene rather than the action. The camera isn’t emotional; it doesn’t react to things. There are a few shots that are handheld, but for the most part, we wanted the camera to be impartial.”

The idea of a detached, voyeuristic perspective is a key visual motif in the story. Many of the tale’s characters are detached emotionally and physically. Eye contact between children and adults is rare; Owen and his mother, whose face we never really see, almost never share the same frame. The film’s intense focus on Owen’s perspective is what draws the audience into the story. “Without using literal POV shots, we tell the story mostly through what Owen sees and experiences,” says Fraser. “The uninflected zooms are used sparingly, to briefly remove us from his world.”

Through testing, the filmmakers decided that the anamorphic 2.40:1 format would suit the project best, and Fraser chose to combine Panavision’s C-Series, E-Series and G-series lenses in his camera package. Reeves observes, “You don’t usually see a film this intimate in a widescreen proscenium, but there’s something amazing about being in a claustrophobic space and still being able to take in the width of that frame. Greig and I also agreed that [anamorphic’s] shallow depth-of-field would help build a sense of mystery, a sense of the uncanny.” Fraser adds, “With anamorphic, the actors could move around the frame without us having to move with them.”

The production tapped Panavision optical engineer Dan Sasaki to develop several custom anamorphic high-speed lenses, as well as some specialty POV glass. The eight lenses Sasaki created, some as fast as Tl.4, effectively halved the amount of foot-candles required by standard anamorphic lenses. The specialty glass included a peephole lens with exaggerated fisheye distortion, a lens meant to simulate the chromatic aberration caused by cheap plastic elements in a toy telescope, and a fractured diopter for the POV of a character whose face was burned with acid. Of the latter device, Sasaki explains, “At first I thought we could under-correct the lens and make it look really ugly with astigmatism and distortion. Greig was trying to suggest how things would look to you if someone fractured your eye, so I made a lens attachment that would screw onto the front of the regular anamorphic lens. It gave the light a crystallized, faceted look, but it was very random and would redirect the light and flare.” Sasaki designed the lens with a tilt-shift bellows that allowed Fraser to compound the effect.

Let Me In is set in the 1980s in Albuquerque, N.M., and the visuals are meant to evoke the movies of that era, when color negatives exhibited more contrast than they do today. Shooting on location in Albuquerque in the fall and winter, Fraser used Kodak Vision2 50D 5201 and Vision3 250D 5207 for day scenes, and his grip/electric team, led by key grip Kurt Kornemann and gaffer Jay Kemp, relied on the existing cloud cover for diffusion, using the snow-covered landscape as an enormous bounce. To bolster the bleak-looking light, 12-light Maxis, 10Ks and Arri T-12 Studio Fresnels were softened with Grid Cloth ranging from ¼ to Full, or bounced off muslin frames. (Only two scenes were shot in direct sunlight, which implies “a sense of merriment and happiness,” says Fraser.)

The line between day and night is the line between life and death for Abby, and the line between misery and comfort for Owen, who must endure the daily torment of bullies at school. The protagonists take refuge in the night, whose look is defined by fluorescent greens and blues, sodium-vapor oranges and tungsten yellows. “Our sodium and fluorescent sources were not corrected except in the apartment courtyard scenes where the tungsten sconces were prominent in the background,” says Kemp. “Initially, the lab [Deluxe Hollywood] was doing a slight green reduction, causing the practical on the apartment building to go a bit magenta. We countered with the addition of ¼ Minus Green on the sodiums, to slightly correct, and made the appropriate notation for the lab.”

Owen and Abby’s first meeting takes place at night in the apartment courtyard, and the pale orange glow of sodium-vapor practicals lends an almost monochromatic look to the scene. Fraser’s crew created the effect with modified industrial sodium-vapor fixtures and custom T Pars built by Los Angeles-based gaffer Phil Walker; the T Pars were fitted with 500-watt and 1K sodium-vapor bulbs. Kemp controlled the T Pars’ light with Rag Place 8x8' frames of Light and ¼ Grid and fabric grids.

In the playground scene, the light alternately hits the actors directly or bounces off the snow. “Direct light can be harsh and unforgiving, and there were times when we manipulated light to make Abby seem less feminine and Owen more feminine,” says Fraser. Eyelights were Litepanels Minis or 1x1's corrected to match the sodium vapors with a mix of Lee 147 Apricot, ½ Plus Green and CTO gels. “We used those Litepanels in nearly every scene,” notes Kemp.

The neutral tones of the playground represent neutral territory for the children, but their home lives couldn’t be more different. Owen shares a tungsten-dominated apartment with his weary, divorced mother that, for all its shabbiness, still feels like a safe haven compared to Abby’s dwelling, a fluorescent-dominated space that is sparsely furnished with second-hand odds and ends. “In addition to the color temperatures, it’s also the quality of light,” says Fraser. “Tungsten has a familiar feel to it, and fluorescent feels electric and artificial.”

Devised by production designer Ford Wheeler, the sets for both apartments were lit with large, round sources Kornemann created called Diving Bells. “They’re essentially oversized space lights that fill the room with a general ambience and can be augmented with additional lights from above and the side,” says Fraser. Sewed up by B-dolly grip Ian Hanna, the production’s Diving Bells were 15'-tall cones of Full Black Grid (or Duvetyn) with a 9'-wide base comprising two layers of Rosco Cinegel 3004 V2 Soft Frost diffusion. They can be equipped with almost any type of source; 6K space lights were used in Owen’s apartment, and Kino Flo Flathead 80s with Cool White bulbs were used in Abby’s (and in other situations where an untraceable source was needed).

“In Owen’s apartment, we used a lot of practical, and we augmented the Diving Bell with either a 3-Lite or 6- Lite Barger Baglite with a Lighttools chimera and fabric grid,” explains Kemp. “When Owen was alone, we lit him with a sodium source from the windows and had the Diving Bell overhead. By contrast, there were almost no practical sources anywhere in Abby’s apartment. Other than her eyelight, the Diving Bell was our sole source there; it was just enough to define the shape of the environment.”

The Diving Bells were primarily used for stage work, but the crew also took them on location to illuminate the arcade where Owen and Abby go on their first date. Kinos with Cool White tubes were used inside and out, the filmmakers’ tribute to the scene in Klute in which Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland make a nighttime trip to a local market. In both cases, says Reeves, “You know these two people shouldn’t be together, but you see in the way she looks at him that she’s falling for him.”

Fraser lit the arcade interior with a bright, slightly green cast, and in the parking lot, the crew rigged a Diving Bell with two Cool White Flathead 80s, creating a pool of light that looked like it was coming from the fixtures inside. Fraser notes, “We didn’t want it to look overly cool, but if we went warm, it would have felt forced. We needed that scene to be as realistic as possible.”

Abby needs blood to live, and slaking her thirst requires her “father” (Richard Jenkins) to kill someone in the night, drag him into the woods, hang him upside down and drain his blood into a plastic jug. “The most terrifying part of the script was the words ‘Ext. Woods-Night,’” Fraser quips. “This is the first time I’ve shot anything in the snow, in the woods, in the dark.

“Abby’s father is not a vampire — he’s a human with bad eyesight,” he continues. “In order to see what he’s doing, we figured he’d have to use some kind of work light.” Accordingly, the filmmakers gave Jenkins a bright camping-light practical that was modified by dimmer-board operator Theo Bott and filled with all the Cool White compact fluorescents that would fit. Kemp recalls, “It was a fairly pure source, but if we needed to give just a bit of an edge to something or extend the throw of the lamp, we used small HMI sources gelled with Plus Green.”

At one point, the father’s grisly activity is discovered, and he abandons his tools and lamp and flees into the woods. In determining how best to create night lighting on a larger scale, Fraser and Kemp considered a Musco, but they “decided it was such a broad source that it would have made the snow too bright and the trees too dark,” says Fraser.

Instead, they used more than 30 1K Source Four ellipsoidals. “We’d shape the light for every tree, or every two or three trees,” says Kemp. “We used the built-in blades to keep the light off the snow and on the trees, cross-lighting and backlighting in the foreground and mid-ground clusters. It was painstaking but quite effective.” Additionally, T-12s and 12-light Maxis lit the larger clusters of trees in the far background, and 1K Fresnels or Lekos served as keylights.

Another lighting challenge was how to create a “no-light” feel for the final scene in Abby’s apartment, a day interior in which all the windows are tightly covered. “Realistically, you’d be looking at a totally black screen,” muses Fraser. “To make the audience believe they’re looking at an image that has no light, you have to pursue a feeling of absolute darkness.” Achieving the effect involved a good deal of testing with Kodak’s Vision3 500T 5219, and Fraser eventually decided to overexpose it by one full stop.

Lighting the set called for the subtlest of approaches, with no perceptible key or fill, just a shallow-focus image on the verge of darkness. The trick was to source the light from above without directly hitting the walls. Kemp used several Octopuses, a small version of the Diving Bell that features eight Duvetyn flaps hanging off the side like tentacles; each held a 1K or 1.5K tungsten JEM Ball (going through a secondary diffusion ring, as with the Diving Bell), and Fraser could direct the light or change the illumination levels by raising or lowering the flaps.

Throughout the production, the filmmakers strove to avoid strong colors. In the digital grade, which was carried out at 2K at Company 3 in Santa Monica, Fraser worked with colorist Shane Harris to desaturate the image a bit further, but little else was done to change what was on the negative. “In a film like this, there has to be a level of honesty about the color in each scene,” says the cinematographer. “If we show the audience a 1980s school or arcade that isn’t fluorescent-lit, they’ll know we’re having them on.”

“The most saturated scenes are in the apartment courtyard, under the sodium-vapor lamps,” says Harris, who worked on a DaVinci Resolve. “For the day exteriors, we tried to give skin tones and shadows a silvery look, which we did by adding blue to those areas.” Referencing stills Fraser took on set (with a Panasonic Lumix DMCGH1), the colorist also fine-tuned the 1980s look, lifting the blacks and suppressing the mid-tones.

“Greig made the movie look exactly the way I hoped it would,” marvels Reeves. “He told me at one point, ‘The most important thing I can do is give you as much time as you need. I can light this to make it look beautiful, but at the end of the day, it will mean nothing if the drama isn’t there.’ I’ve never had a cinematographer say that to me. His respect for the actors, the schedule, and my job as the director affected the film profoundly.”

TECH SPECS

2.40:1

Anamorphlc 35mm

Panaflex Platinum, Millennium XL

Panavision lenses

Kodak Vision3 250D 5207, 500T 5219; Vision2 50D 5201

Digital Intermediate

Printed on Fuji Eterna-CP 3513DI

THE CAR

On a quest for blood to slake Abby's thirst, the vampire's guardian (Richard Jenkins) hides in the back seat of a car and attacks one of its occupants at a gas station. The crew exploited a roofless prop car to capture parts of the sequence.

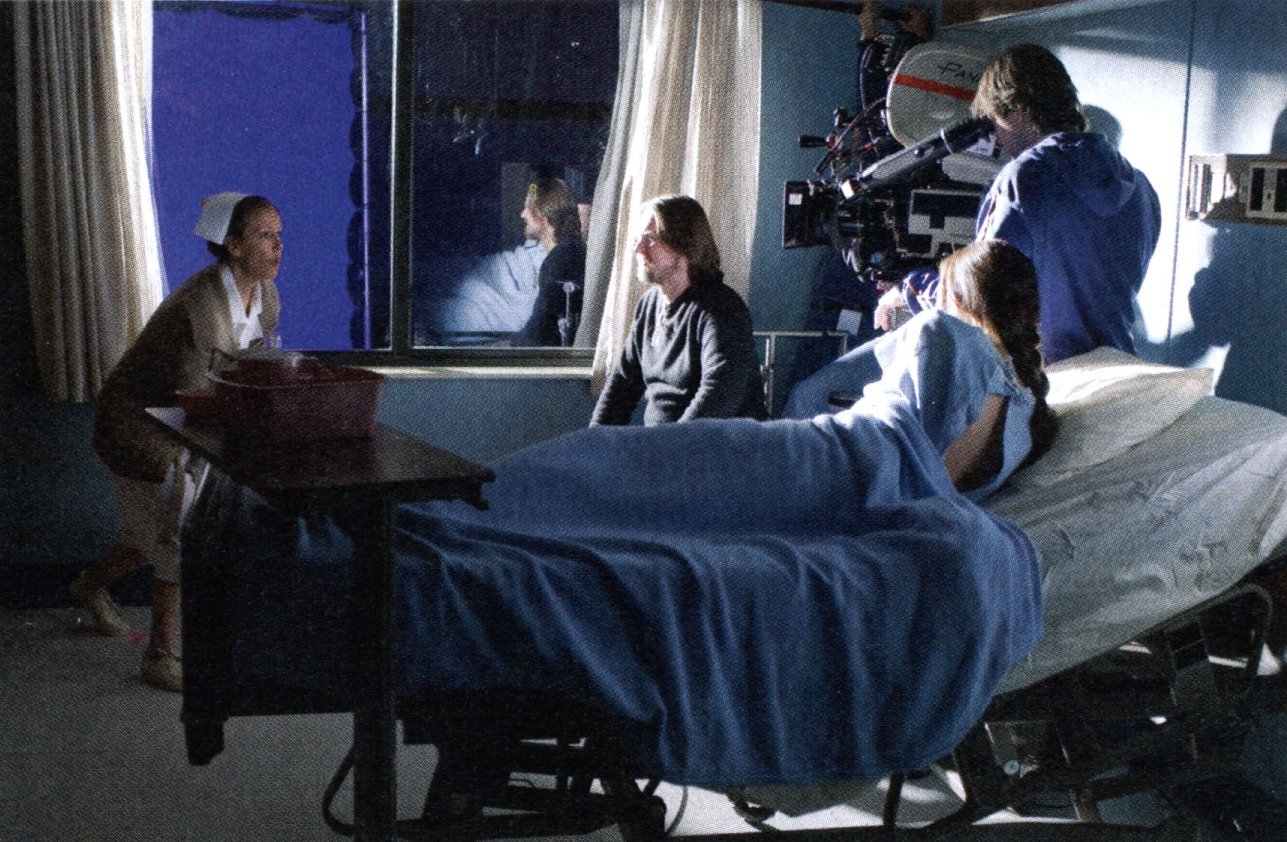

THE FIRE

After being hospitalized, a victim of Abby's begins transforming into a vampire, but bursts into flames when an unwitting nurse allows daylight into the room.

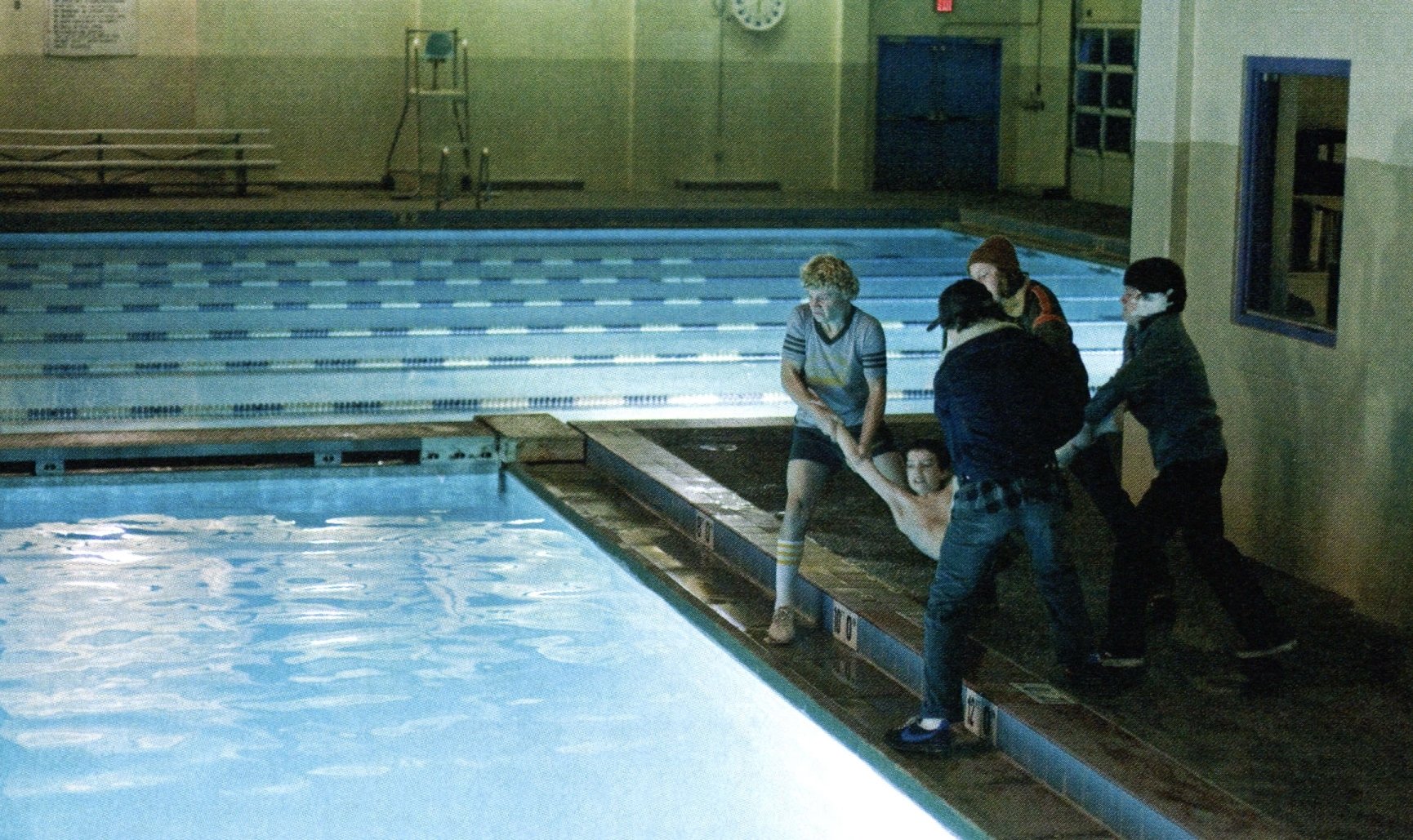

THE WATER

Underwater cameras were used to capture Owen's distress after he's thrown into a swimming pool by a group of sadistic bullies.

Both Fraser and van Hoytema were later invited to become ASC members.