Shot Craft: Tools for Camera Movement

A survey of the on-set implements frequently employed to add momentum and meaning.

A moving camera can accentuate the drama of a moment, add mystery or interest to a shot, or otherwise help tell the story. But with so many tools for achieving camera moves, how do you decide which one is best for the shot at hand?

It always starts with the script and a discussion with the director about what they envision. Then, you start to look at the tools that fit your budget and your plan. And it’s always a good idea to consult with your key grip for suggestions.

Here are some considerations.

The Cheapest Option

“Handheld” can mean the camera is on your shoulder, in your hands, cradled in your arms, propped on your hip, balanced on your knee or any variation thereof. Handheld is generally the fastest and cheapest form of camera movement, as it only requires a human and a camera.

The operator can often be improvisational in their movements as they follow the subject(s), allowing for quick execution of shots; they can rotate their body to pan the camera, walk around to execute changes in vantage point, and even transition from holding the camera over their head to dropping it down to ground level. More finessed handheld operation requires some sort of hardware to provide additional support for the shoulder, arms or hip. A good operator can isolate the camera from their body movements, including their own breathing.

Handheld can convey immediacy and energy, and many filmmakers use it to heighten tension. If a character is on the run from a relentless killer, for example, you might use handheld to accentuate their panic and desperation.

Though it’s generally advised that too much handheld can induce nausea in some viewers, there are examples of handheld-heavy productions that have been quite successful. Paul Greengrass’ The Bourne Ultimatum (AC Sept. ‘07) was shot by Oliver Wood with a great deal of handheld — sometimes aggressively so — and this gives the action thriller a documentary-like immediacy. Indeed, the Bourne films are known for this look.

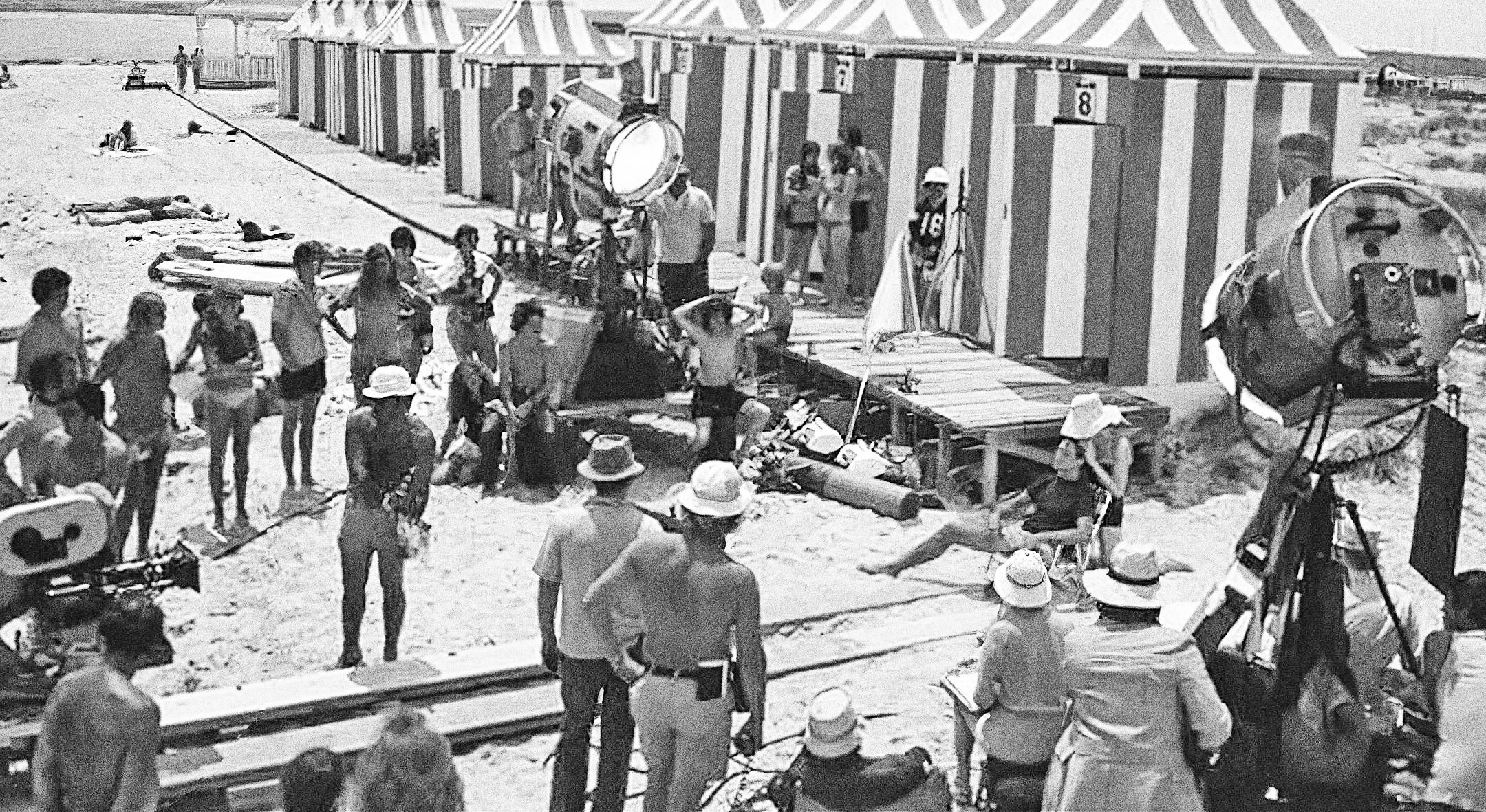

Hello, Dolly

A longtime staple in cinema’s visual language, the dolly provides a stable platform, usually on wheels, that can move a camera horizontally from one position to another. The most basic version is the “doorway” dolly, a plywood platform on casters that has a handle, enabling it to be pushed or pulled. The most elaborate dollies have such features as specialized wheels, perfectly smooth track and a hydraulic boom arm that can change the camera’s height along with its horizontal position.

Dollies provide smooth, gliding movement. In all but the simplest configurations, the camera operator rides on a seat — or stands or kneels — along with the camera. Dollies can be used with straight or curved track, or directly on a smooth floor. High-end dollies can switch from rear-wheel steering to four-wheel steering to refine moves.

Though many think of the dolly as a way to get from Point A to Point B, it can also be used subtly — and to save a take. In an over-the-shoulder situation where the camera is behind one actor looking at another, if either of the actors misses their mark, a good dolly grip will notice and adapt by dollying slightly to keep the errant actor from blocking the other. A symbiotic relationship between the camera operator and dolly grip is essential.

The slow creep-in, wherein the dolly almost imperceptibly moves closer to a character in a moment of crisis or realization, is especially effective.

On Vertigo (released in 1958, covered in AC Nov. ‘96), Alfred Hitchcock and Robert Burks, ASC famously combined a dolly with a zoom to convey the protagonist’s acrophobia. This combo has since been used by many filmmakers, notably Steven Spielberg and Bill Butler, ASC, who used it on Jaws for the moment when Chief Brody (Roy Scheider) witnesses a fatal shark attack from the beach. The camera dollies away from him while zooming in, keeping Brody the same size in frame as the background closes in on him. It’s a very tricky technique, but powerful when properly executed.

Slip Slidin’ Away

A slider is, in essence, a mini dolly. It’s usually a small platform on skateboard wheels that slides along a track, and it can be set up quickly by one person.

The track is usually 8' long or shorter, making the slider a good tool for small moves. The track is often raised off the ground by stands and it can be incredibly compact. Sliders are often used on a fairly fixed subject such as a product or a seated person, and they work great for a POV that just peeks around a corner.

Telling the difference between a dolly shot and a slider shot isn’t easy, so I’ll offer an example from a project called Terminus that I made with cinematographer Kaity Williams. Putting a slider inside a car, we tracked the camera from the back seat, shooting an over-the-shoulder of the driver, and slid to a profile shot from the front seat. The shot couldn’t have been accomplished with any other tool without gutting the inside of the car or cutting it in half.

Gimbals, Gimbals Everywhere

There are many versions of the handheld gimbal — a computer-controlled and counterbalanced multi-axis head that can not only provide pans and tilts, but also counteract any jitter or unwanted motion of the operator’s body. Gimbals are available in various sizes, for the smallest HDSLR to the largest digital-cinema cameras.

Gimbals are held in one or two hands, and the camera’s pan/tilt/roll can be controlled by the operator or by another crewmember (the latter to allow the gimbal operator to concentrate purely on the camera move). Gimbals are typically used to facilitate work in tight spaces. Because they’re small and flexible, it’s even possible to design a hand-off between two operators to pass the camera through an open window and the like.

The gimbal serves as a hybrid between a dolly and handheld, as it smooths the action while an operator keeps the camera in their hands. Fast, non-linear moves are good ones for the gimbal: A character is late for work, jumps out of the car and runs into the office as the camera gives chase.

The Creator (AC Nov. ‘23), photographed by Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS and Oren Soffer, made extensive use of a handheld gimbal and a small prosumer camera to give director/camera operator Gareth Edwards complete creative freedom for each scene.

Steady Does It

The stabilizer was pioneered by ASC associate member Garrett Brown when he invented the Steadicam in the mid-1970s. The stabilizer uses a vest to distribute the weight of the camera and rig to the operator’s hips and shoulders, and a combination of isolating and damping spring joints are mounted to the vest. The camera is placed on a pedestal at the end of the spring arms and can “float” in front (or to the side) of the operator.

The pivot joint for the pedestal is positioned at the exact center of balance for the pedestal and camera (with lens and all attachments), which allows for effortless pans and tilts. There is limited up/down movement because the motion-isolating spring arms have a small vertical range.

360-degree pans are possible, and horizontal movement is accomplished by the operator moving with the rig attached. It’s also possible to tip the camera side to side, but on the traditional stabilizer, the camera does not stay upright, so the image tilts with the camera. Modern variations on the stabilizer correct this and allow the pedestal to be tilted while keeping the camera upright, which can provide greater height adjustment of the camera from the operator’s feet to above their head in a single shot.

The stabilizer is used for a countless array of moving shots, but it is especially popular for walk-and-talks, following action, or long “oner” shots that incorporate complex choreography of camera and talent.

The stabilizer’s large size tends to give it a smoother, more drifting/floating feel than a gimbal, but it also makes it harder to use in tight spaces (though some operators are wizards). The stabilizer is better suited to extended and graceful moves.

A famous use of Steadicam, the first stabilizer — detailed in AC’s August 1980 issue by Brown himself — is Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, shot by John Alcott, BSC. The floating camera following young Danny (Danny Lloyd) as he pedals his Big Wheel through the halls of the Overlook Hotel lends those scenes an incredible eeriness.

Cranes Are Flying

The crane has by now formed its own visual vocabulary in cinema. Placing the camera on the end of a long shaft with a fulcrum positioned far from the camera (with physical weight added to the short back to counterbalance the arm, camera and any additional payload) allows for the camera to move in an arc from ground level to as high as the specific crane configuration will allow — some as high as 100'.

Originally, the crane had to carry the camera, operator, assistant and sometimes the director. Thanks to remote heads and remote monitoring, that’s no longer necessary. Eliminating the need to place humans on the end of the crane shaft has also enabled longer and more compact cranes (and safer sets).

Small (6'-12') cranes are often called jibs. Some cranes can telescope along the shaft to adjust the length of their arm. Although cranes are often used to achieve high shots or large differences in height during a shot, if you have enough room in your shooting area and a telescoping crane, you can use it as a “dolly on steroids.”

Some cranes are also mounted to rolling platforms, motorized platforms and even cars. A remote-operated crane attached to a vehicle has become a staple for photographing other moving vehicles. One of the most common applications for the crane is a transition shot starting high on an establishing view of a location and slowly dropping into the scene.

A particularly astounding crane shot appears in Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946), shot by Ted Tetzlaff, ASC. It starts from a second-floor balcony and drops down to the hand of Alicia (Ingrid Bergman) and a macro shot of a key in her clenched fist.

Up and Away

Filmmakers seeking bird’s-eye views or other aerial perspectives can use drones, planes, helicopters and even hot-air balloons. Drones allow for a wide range of shots, including some formerly accomplished with helicopters and cranes. Incorporating gimbal stabilizers into the cameras on drones or helicopters makes them very powerful tools for transitions, establishing shots, following a fast-moving object such as a car or horse, and, of course, tracking another aerial object.

A recent extraordinary example of air-to-air photography is Top Gun: Maverick (AC June ‘22), directed by Joseph Kosinski and photographed by Claudio Miranda, ASC, ACC. The dog-fighting sequences of real jets being chased by camera jets are jaw-dropping.