The Chill Atmosphere of Fright Night

“The genesis of the script grew out of my idea to make the vampire movie contemporary.”

This article originally appeared in AC, Oct. 1985. Some images are additional or alternate.

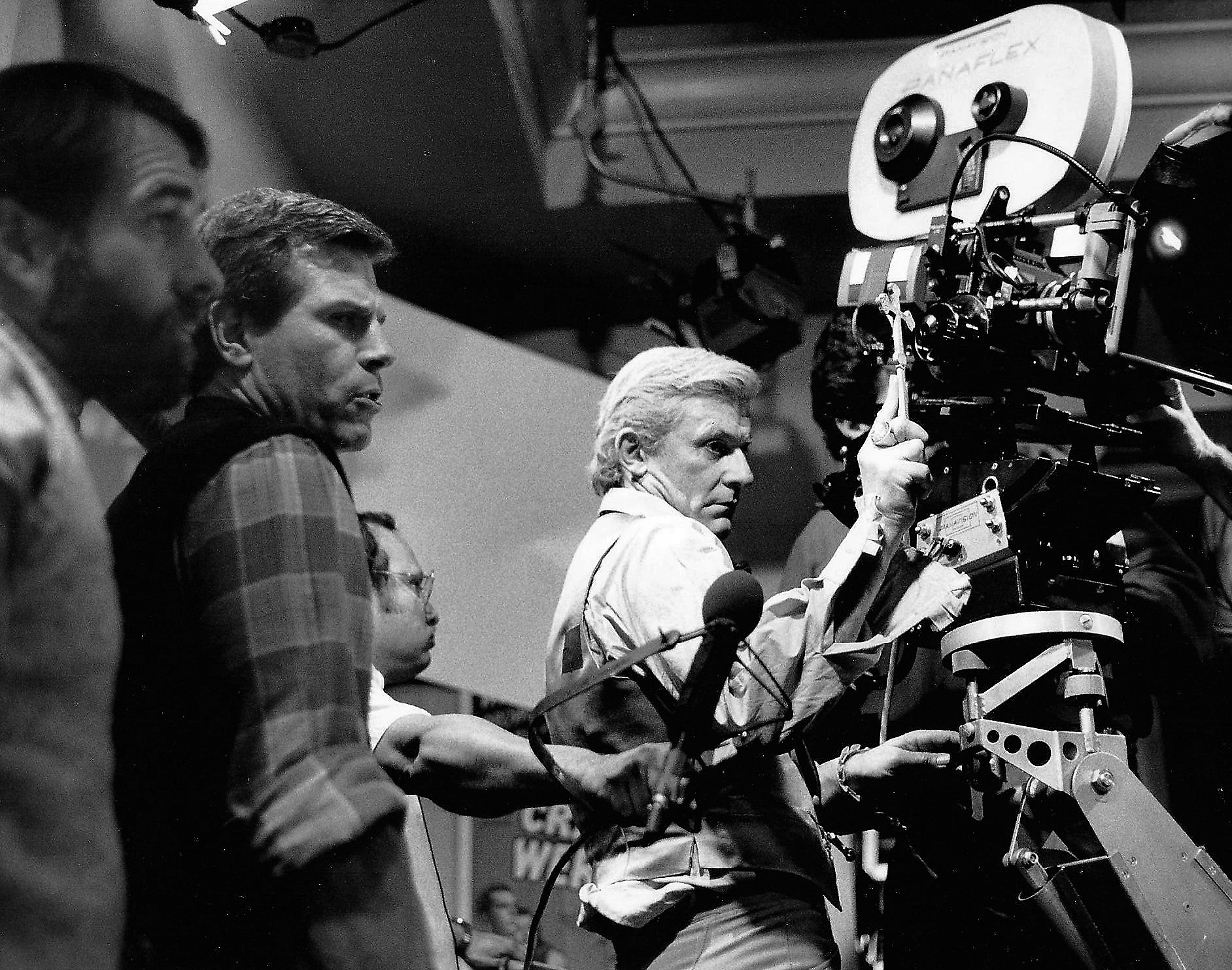

Unit photography by Ron Batzdorff

“Fright Night is a vampire movie,” said Jan Kiesser, director of photography, “but it’s a vampire movie with a story.”

In what seems to be the latest trend in fantasy films — that of emphasizing people and script over backgrounds and spectacular special effects — writer and first-time director Tom Holland (whose previous screenplay credits include The Beast Within, Psycho II and Cloak And Dagger) wanted his film to be that way as well. “The genesis of the script grew out of my idea to make the vampire movie contemporary,” said Holland of his film. “The genre faded in the 1950s because most vampire films then were still period pieces. Nobody knew how to bring them up to date. I like to think that this picture works well in contemporary terms.”

“Photography should not be jarring. If the audience’s attention goes to the photography, that means their attention is not on the story — which is where it should be.”

Fright Night is about 16-year-old Charley Brewster (played by newcomer William Ragsdale), an avid horror film watcher who is devoted to the nightly ritual of viewing Fright Night Theater, a horror movie show in the Elvira vein that is hosted by aging actor Peter Vincent (played by Roddy McDowall), known as The Vampire Killer.

One night, while watching the show with his girlfriend, Amy (played by Amanda Bearse), Charley looks out of his second-story bedroom window to the vacant house next door. There, he sees a man — a vampire — kill a woman. Charley soon learns that their new next-door neighbor is attractive Jerry Dandridge (played by Chris Sarandon).

Charley tries to convince his friends that Jerry is really a vampire, and, at first, nobody believes him. But, as the murders of young girls continue to fill the morgue of the tiny midwestern town with corpses, Charley’s friends slowly begin to realize that he may be right. Finally managing to convince and recruit Peter Vincent: Vampire Killer, he and Charley head to the house to destroy Jerry Dandridge, vampire.

Countless vampire films have been made — from classics such as Bela Lugosi’s staple performance as Count Dracula to the early ’70s exploitation films like Count Yorga: Vampire. Unlike modern vampire films that have been produced in the last several years attempting to depart from tradition (The Hunger, Lifeforce), Holland wanted to stay true to the genre and was determined to do it. “I wanted to respect all of the conventions of the traditional vampire story — the coffin beds, empty mirror, and the like — but place them in a contemporary setting,” said Holland.

As director of photography, Kiesser’s job was to do the same thing in the look of the picture: bring traditional horror film lighting (shallow pools of light and black shadows) into the same contemporary setting.

Originally a pre-med student, Kiesser was injured in an automobile accident that forced him to drop out. Before he could return to school, however, he was drafted and was stationed in Europe. There, he became involved in photography, and in order to earn extra money so that he could travel when his tour was complete, Kiesser took a job as a projectionist in Special Services. The experience had a resounding effect on him. “I saw a different film each night for the entire six months I worked there.” said Kiesser.

Returning home to Los Angeles, Kiesser realized that he lived right in the heart of the motion-picture industry and it was at that time he decided to become a cinematographer.

His first job was at Wally Bulloch’s Animation Camera Service where he was a cartoon cameraman. “Wally was very supportive,” said Kiesser, “He was always trying to help young people who wanted to get into the business. I really owe him a lot.” Kiesser rapidly got work as a second assistant, eventually landing assignments with Gordon Willis, ASC and Haskell Wexler, ASC, as well as operating for Donald M. Morgan, ASC, on the Emmy-nominated Elvis.

His big break came when Kiesser got on as a camera operator for Academy-Award-winning cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC. “I worked with Vilmos for four years,” said Kiesser, “and he really was a great teacher. He taught me to never to be set in your ways about anything. He always told me to be open about new ideas and be willing to use new techniques.” Soon after that, Kiesser landed his first job as a full director of photography, on director Sidney Furie’s Purple Hearts. That film was followed by Choose Me, The River Rat and then Fright Night.

“There was an early decision on this picture that we needed to show the contrast between Jerry Dandridge as a creature of the night and Charley Brewster as a creature of the light,” said Kiesser, “I was going for a definite difference and to accomplish this we used warmer colors on the ‘good guys’ and cooler colors on the ‘bad guys.’ Charley, for instance, is always in an orange backlight, while Jerry is always in a cold, blue backlight. Sometimes it’s more subtle than others, but it is always there.”

Although seeking contemporary lighting, Kiesser wanted to make sure that he remained true to the genre. “We watched a lot of old vampire movies,” said Kiesser, “as well as other films such as The Prisoner of Zenda which has stunning black-and-white cinematography by James Wong Howe, ASC. But one of the best, and most interesting pictures we watched was Val Lewton’s The Cat People, photographed by Nick Musuraca, ASC. The great thing about that picture is that there were so many shadows and pools of light and dark that a whole lot was left up to the imagination — which is really terrific. Although I like to have details in the shadow areas, we went for The Cat People ‘look’ on Fright Night. We tried not to show everything.”

Pre-production on Fright Night began in October of 1984, and principal photography began at Laird Studios in Culver City on December 3, 1984 — the same studio where Cat People was filmed in 1942.

According to Kiesser, Holland made excellent use of storyboards. “Tom really did his homework. He came in with the entire picture boarded in these rather crude drawings, but at least they showed what he wanted — and he knew what he wanted.”

“Tom had some definite ideas about some very specific things,” said Kiesser, “like using the Louma crane for certain shots.”

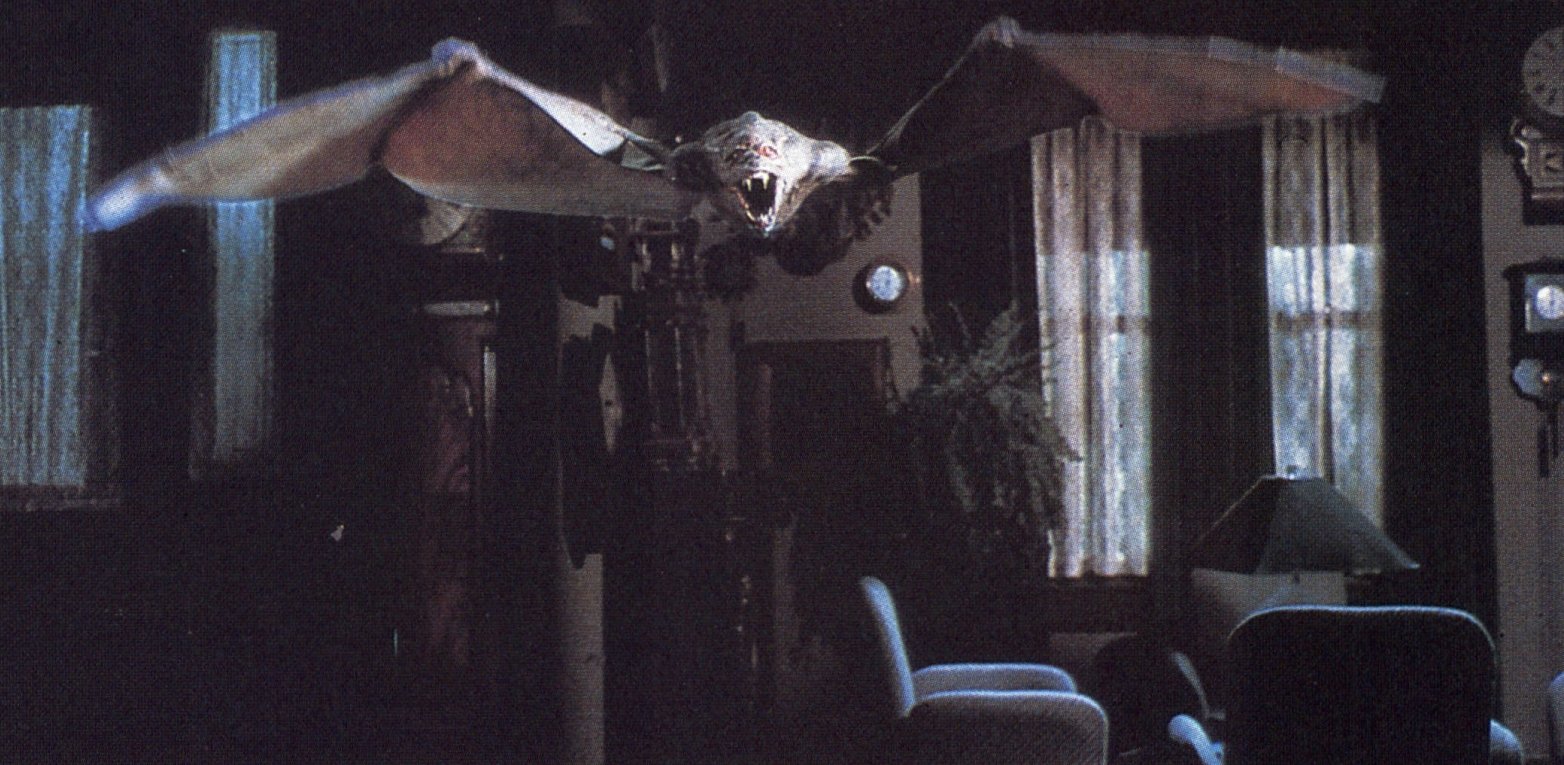

Early in the film, Charley sees Jerry Dandridge kill a young woman in the second-story bedroom of his house. Looking down into the yard of the Dandridge house, Charley sees Billy Cole, Jerry’s “live-in carpenter” and partner in ghoulish crime, carrying a plastic bag with a body in it out to a car. Thinking this is his chance to prove Dandridge a vampire, Charley runs downstairs and goes outside to get a closer look. As Charley watches from the bushes, a bat swoops down from the roof of the Dandridge house and changes into Jerry when it reaches the lawn. “Tom knew that this shot would be perfect for the Louma crane,” said Kiesser, “Jerry’s point of view is perfectly portrayed by the crane.” According to Kiesser, Holland wanted to use the Louma much more, but time prevailed, permitting only two Louma shots to end up in the final film.

Exteriors of both Charley’s and Jerry’s houses were photographed on the Disney backlot while downtown Los Angeles served as other locations. For the night work at Disney, Kiesser used arc lights on Condors as his moonlight source. The entire film was photographed on Eastman 5294, but, because some of the shots were going to later serve as plates for optical effects work to be done by Richard Edlund, ASC, at Boss Film, Kiesser had to work at a high footcandle level. “For this picture, I rated the 5294 at a base rating of 200 ASA rather than the base of 320 ASA as given by Kodak,” said Kiesser, “Since some of the camera negative was going to be used with 70mm over at Boss, we needed not only to minimize grain and contrast, but we also needed a properly dense negative. Rating the 5294 at 200 ASA seemed to do that. Also, we were working with an aperture of .4 most of the time, which meant we sometimes had a 200-foot candle key. That’s a lot of light going around.”

Another bonus of working at the slower rating was the increased color saturation and the rendition of good, solid blacks that both he and Holland felt were necessary to the look of the picture. By rating the 5294 at 200 ASA, Kiesser found he was able to print in the high 30s (at MGM, a 50-point print scale is utilized — the higher the number, the denser the negative. A 30 is a very dense negative for exterior night work on 5294).

During the course of the film, both houses are shown to change in relation to one another. As the film progresses, the Dandridge home, increasing its evil, changes until it looms over the Brewster house.

In order to depict these changes, Kiesser did several things. “The lighting of the exterior of Jerry’s house goes from a rather ordinary blue, moonlit look, to a decidedly eerie green look with dry ice fog pouring off the outside.”

Also planned in the early discussions of the visual look of the picture with production designer John DeCuir, Jr. (son of veteran designer John DeCuir, whose recent credits include Ghostbusters), were actual physical changes of Jerry’s house. “We wanted to really build parts of Jerry’s house bigger than Charley’s house and show it physically looming over,” said Kiesser, “Unfortunately, budget prevailed.” However, the effect is not lost as Kiesser accomplished the same look during principal photography. “We put the camera up on a crane with a 24mm lens,” said Kiesser, “and we got the same sort of distortion.” On film, Jerry’s house appears to stretch up and over Charley’s house in the background.

Another device used was the Panatate. Similar to the type of device used for spacewalking scenes in 2001: A Space Odyssey, the Panatate rotates the camera on the axis of the lens. Like the Louma crane, the Panatate was used to denote Jerry’s point of view in the sequence where he crawls down the outside wall of his home to look through the window at Peter Vincent and Charley. The shot begins upside down and then rotates to the right side-up as it looks through the window. The effect is both disorienting and chilling.

One of the sequences shot on location in downtown Los Angeles is Evil Ed’s demise in the alley. A friend of Charley’s who ostensibly refuses to believe in vampires, Evil Ed wants to take a shortcut through a dark alley. Charley tries to stop him, but Ed goes through anyway.

The alley is filled with pools of light, dark shadows stretching in every direction and atmospheric clouds of steam and fog. “We used a number of different things for smoke and steam effects,” said Kiesser, “We used smoke cookies, a unit called an oil cracker, regular moll fog, and even dry ice. However, we primarily used steam for the alley sequence where Evil Ed runs into Jerry Dandridge.”

The other sequence shot in downtown Los Angeles was the Club Radio scene. Built in what used to be Andrews’ Hardware, Kiesser said the main thing that attracted the production to the abandoned, gutted, building were some of the architectural features inside. Not much work was needed to transform the cavernous building into the throbbing Club Radio.

“The interesting thing about the Club Radio sequence,” said Kiesser, “was the use of spotlights.” Blues, purples, pinks, yellows, and greens all pulse and move to the beat of the music inside the club. “We had the entire place rigged with HMI spots that could rotate in any direction and then they were hooked up to a computer and programmed for certain moves to the beat of whatever music we used for background.”

Amy, Charley’s girlfriend, is seduced by Jerry on the dancefloor at Club Radio and taken back to his house. Charley rushes to Peter Vincent’s house and convinces them that they have to save Amy from the clutches of the vampire. Finally agreeing, the frightened Peter Vincent and Charley head to Dandridge’s house for the final confrontation and the climax of the picture.

As they approach the house, green light and dry ice fog pour from it like a ghostly, evil presence. Together, Peter and Charley enter the house and fight Billy Cole (Jerry’s assistant zombie) and defeat him. At that moment, Jerry appears and dawn begins breaking.

Chasing Jerry down into the dark basement, where the windows have been painted black to prevent sunlight from entering, Peter manages to get him out of his coffin bed. At this point, the interiors of the basement are lit cold and blue, denoting that the evil Jerry is still in power. But then, Charley begins breaking out the black glass, causing great shafts of sunlight to enter. To achieve the effect of bright morning sunlight, Kiesser used the extremely bright Xenon Skytrackers and placed them outside the windows of the basement set, pointing in. Specific windows were broken out in a certain order, creating a pattern of shafts on the set.

Finally, Jerry is cornered by the shafts and destroyed by the light. The final shot of the picture, shows Charley, Peter, and Amy in a very warm light, denoting their triumph over evil.

“I usually come in with a pre-conceived notion of what I want to accomplish with a scene,” said Kiesser, “and that usually evolves as I watch the scene unfold with the actors. What I want to do with a scene usually never changes, but how I accomplish it usually does. I like to play a realistic source, but it is really relative to the scene itself.

“Photography should not be jarring. If the audience’s attention goes to the photography, that means their attention is not on the story — which is where it should be. That doesn’t mean that a picture can’t look pretty. But you have to tell the story.”

Cinematographer Jan Kiesser was later invited to become an ASC member, and would go on to shoot just features as Some Kind of Wonderful, Georgia and Fido, as well as television series such as Falling Skies and The Flash.

You'll find our complete story on the film's visual effects and creature work here.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.