The End of the Century as We Knew It — The 1990s

American Cinematographer chronicles a decade of change in the world of visual storytelling.

American Cinematographer chronicles a decade of change in the world of visual storytelling.

The 1990s marked a significant transitional point in cinematography and filmmaking in general. The decade opened much like its predecessor, the more exuberant ’80s (as discussed in last month’s issue), but as it wore on, the stories told, and their supporting images, became much more grounded and certainly more dramatic and dynamic. This is reflected in the photographic techniques that emerged during that time, as cinematographers increasingly explored how to manipulate the contrast/tonal characteristics of their images through special laboratory processes.

AC dug into this trend in the article “Soup du Jour” (Nov. ’98), a detailed analysis of silver-retention processes such as bleach bypass, Technicolor’s ENR and Deluxe Laboratories’ CCE and ACE, as well as the cross-processing of reversal film and the short-lived revival of the dye-transfer printing process.

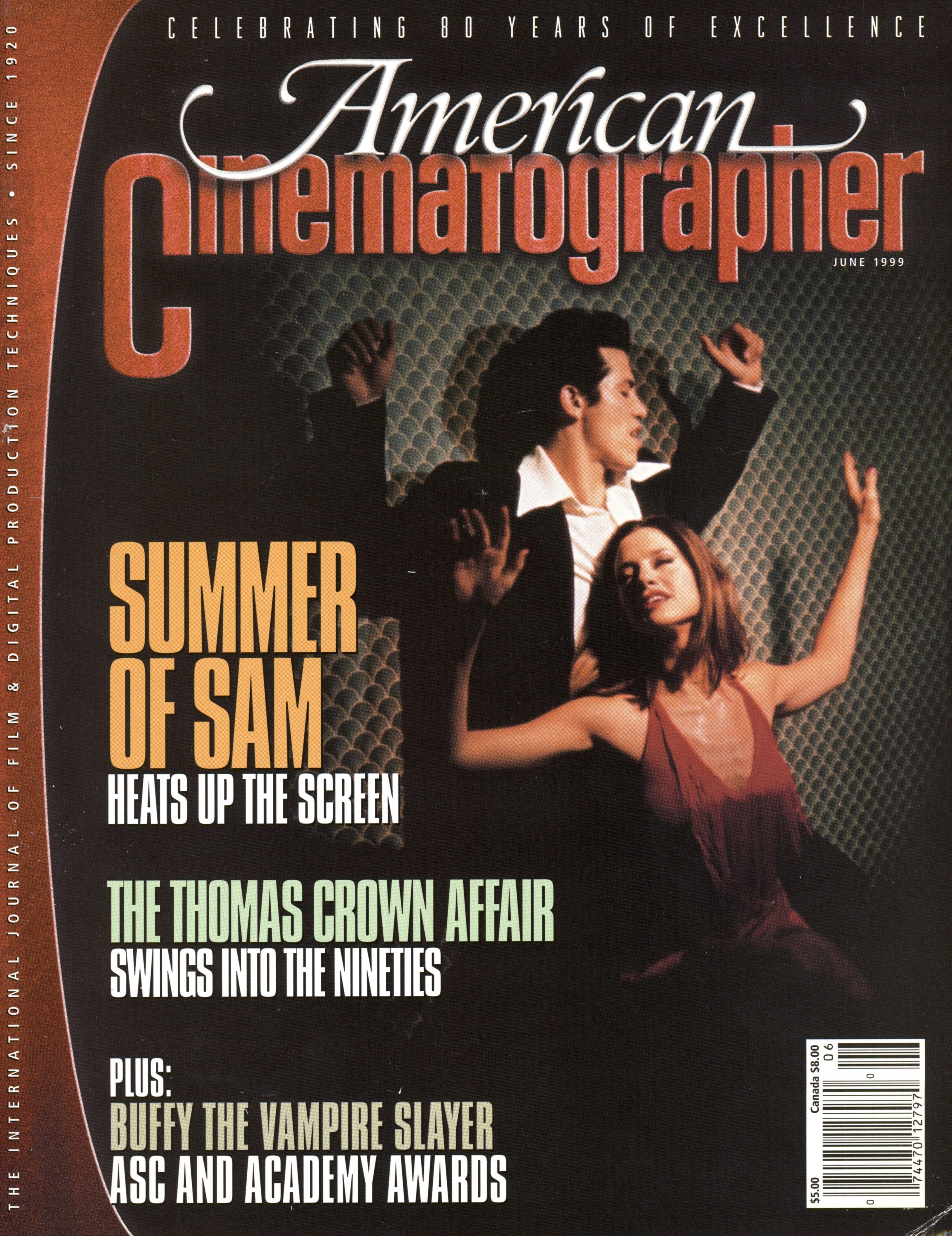

AC covered dozens of films and even TV series that incorporated these techniques, among them Bringing Out the Dead (Nov. ’99), The Wings of the Dove (Nov. ’98), Snow Falling on Cedars (June ’99), an episode of Chicago Hope (Nov. ’99), Alien: Resurrection (Nov. ’97), Bulworth (June ’98), Evita (Jan. ’97), Fight Club (Nov. ’99), L.A. Confidential (Oct. ’97), Little Buddha (May ’94), Saving Private Ryan (Aug ’98), The Game (Sept. ’97), The Rock (June ’96), Se7en (Oct. ’95), Sleepy Hollow (Dec. ’99), Ronin (Oct. ’98), Summer of Sam (June ’99) and Three Kings (Nov. ’99).

In discussing his approach to Se7en, Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC told AC staffer David E. Williams, “On the very technical side of any film, the most important thing to me is to control a stock’s contrast, or gamma curve. I usually shoot on Kodak, and when you ask for [52]48 or [52]47, you get a certain latitude, a certain curve. So I like to change the curve according to the tone of the story, or even to play with it from scene to scene.”

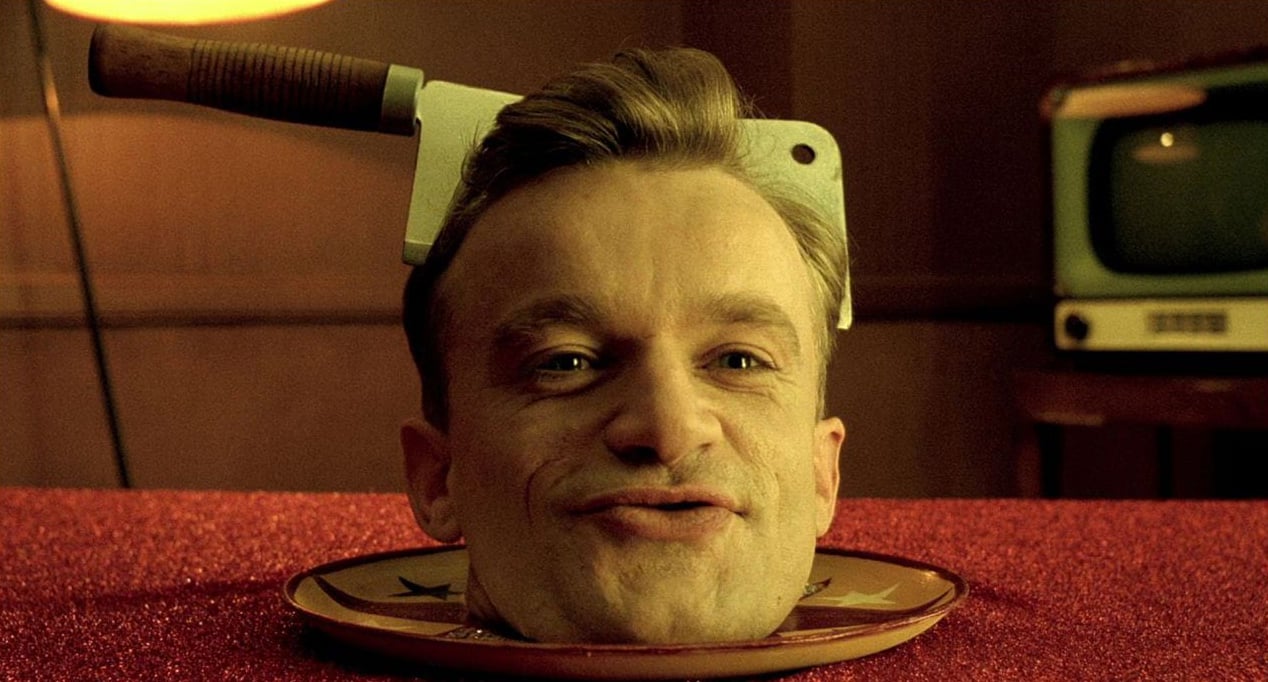

To that end, Khondji began his color work, leading to further experimentation with a silver process that called for his stock to be run first through color baths and then resouped as black-and-white, restoring silver to the negative and resulting in rich blacks while simultaneously desaturating colors. Delicatessen was the first feature to benefit from this procedure. “The directors [Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet] wanted very contrasty images — something that would put color into the world of realism poetique, a current of the French cinema of the 1930s and ’40s which was very expressionistic. So I had to increase the contrast beyond what I could get from lighting.”

As the blacks were so deepened by the silver process, Khondji would first use the Arriflex VariCon system to add detail in the shadows, while simultaneously pushing the negative a stop to saturate the remaining colors as much as possible. “We put more color back in at every step we could, while at the same time getting these strong blacks — like ink.”

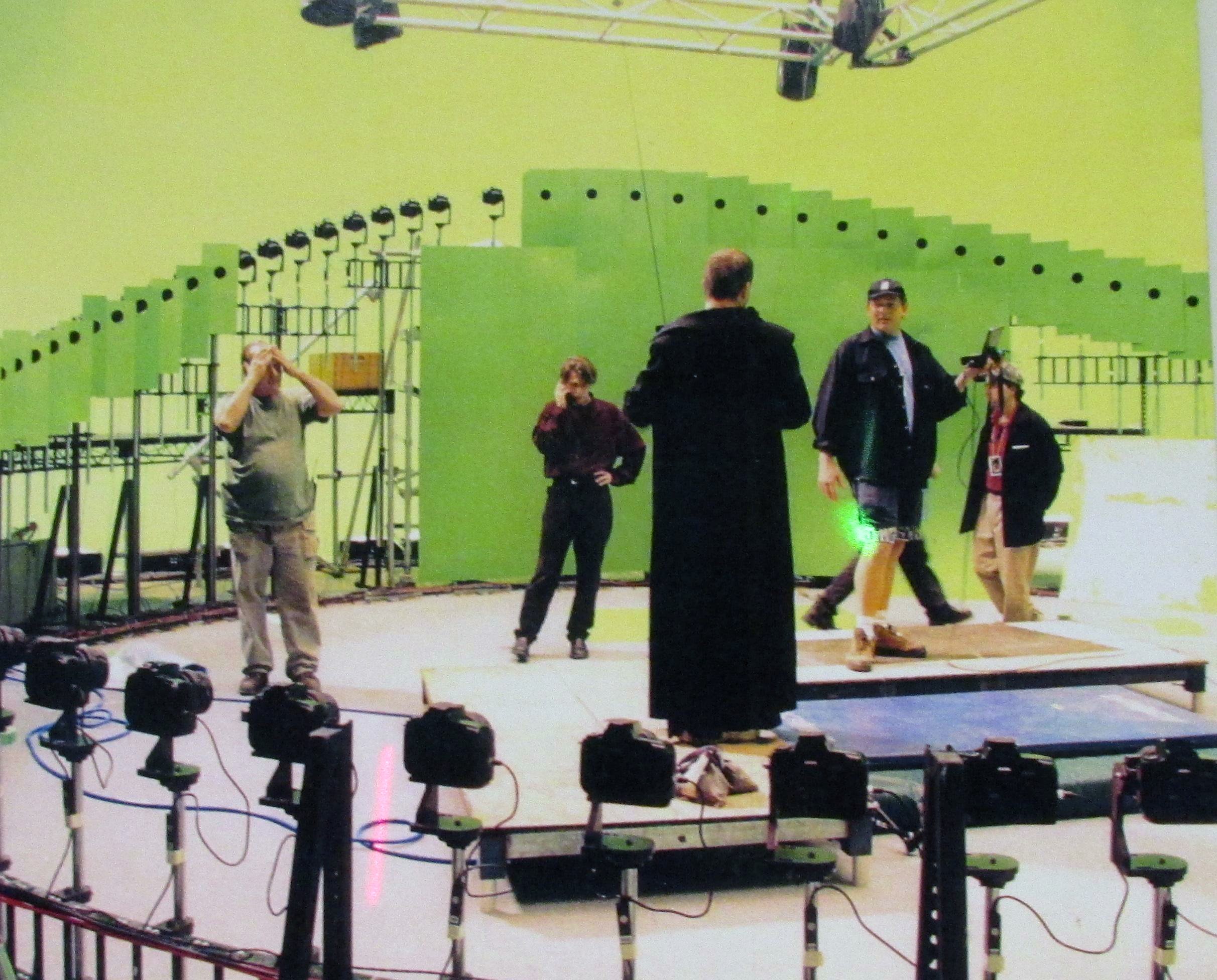

In the August 1991 issue, Steven B. Poster, ASC wrote an article detailing an early test of an HD-camera system from Japanese manufacturer NHK, and eight years later, director George Lucas and cinematographer David Tattersall, BSC discussed using prototype Sony HD cameras (incorporating the new 24p frame-rate standard) for a small scene in Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace (Sept. ’99). However, Tattersall attests that “the extensive use of bluescreen on Episode I is what made shooting the picture so very different from any other I’ve done. The sheer amount of bluescreen material was amazing.

“On sets where the bluescreens were such a large portion of the frame, light balancing became more difficult. The temptation would be to pitch for a brighter exposure on live-action foreground elements to contrast them with the bluescreen. However, if the background plate was to consist mainly of bright tones, a darker exposure would be more effective. But naturalism was always the aim, and we sought to keep the light as soft as possible.”

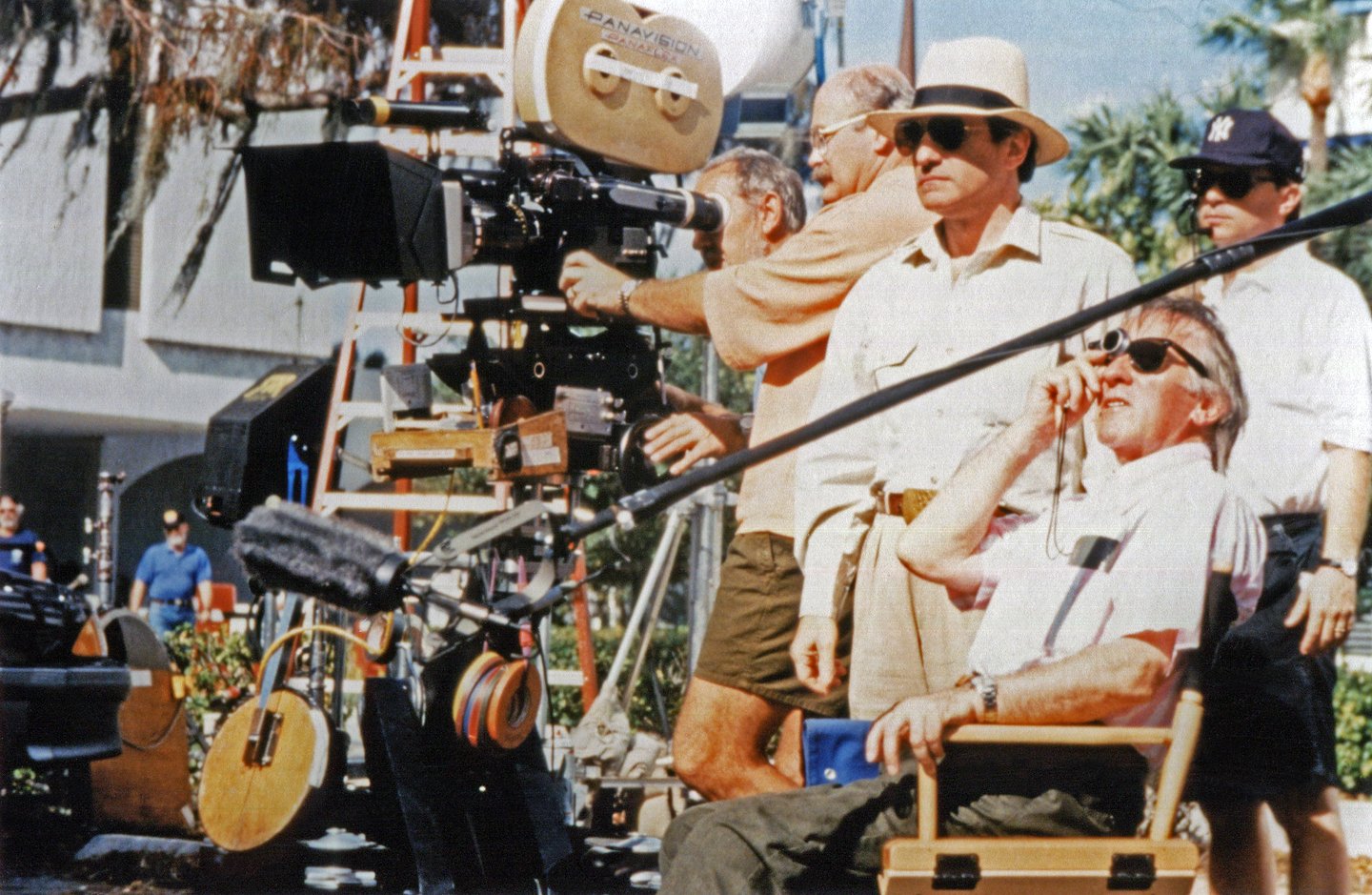

The decade also saw Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, James Cameron and Oliver Stone release some of their most influential and successful films, many of which were covered in the pages of AC.

After Spielberg and Dean Cundey, ASC flipped the visual-effects world on its head with Jurassic Park (June ’93), the director launched a new collaboration with Polish cinematographer Janusz Kaminski on Schindler’s List (Jan. ’94).

Spielberg and Kaminski rounded out the decade with The Lost World: Jurassic Park (June ’97), Amistad (Jan. ’98) and Saving Private Ryan (Aug. ’98), and their creative partnership continues to this day. “We are collaborators and friends, and we give each other tremendous emotional support,” Spielberg told Stephen Pizzello — who now serves as AC’s editor-in-chief. “Because we have so much mutual respect, neither of us wants to let the other down.”

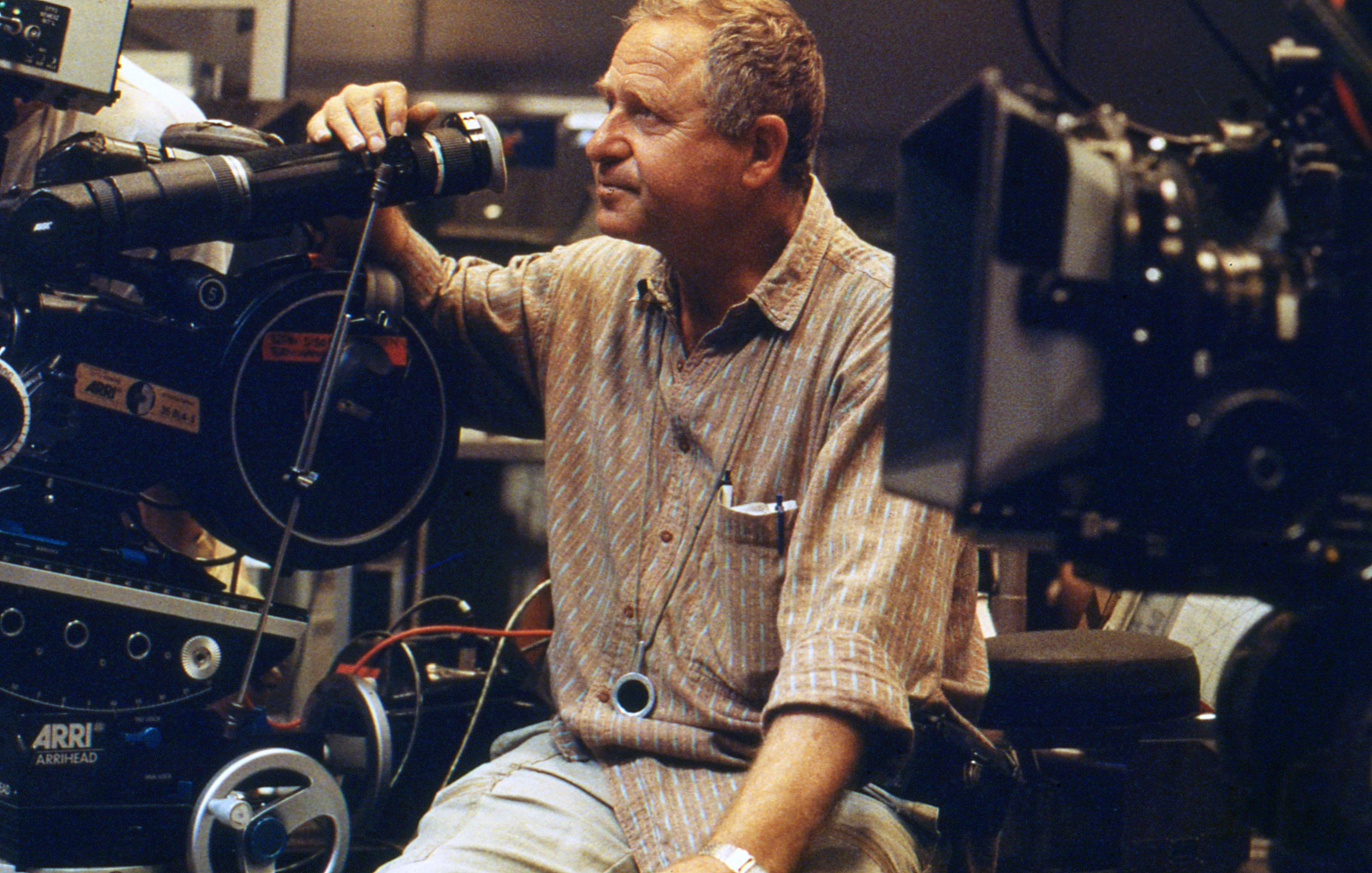

Scorsese’s output in the ’90s encompassed a range of eras and subject matter. After remaking Cape Fear with Freddie Francis, BSC (Oct. ’91), he reunited with Michael Ballhaus, ASC, BVK for the Edith Wharton adaptation The Age of Innocence (Oct. ’93). Scorsese then sparked with a new collaborator, Robert Richardson, ASC, on Casino (Nov. ’95), and they went on to partner on Bringing Out the Dead (Nov. ’99). Between those projects, Scorsese enlisted Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC to craft the lush visuals of the Dalai Lama story Kundun (Feb. ’98).

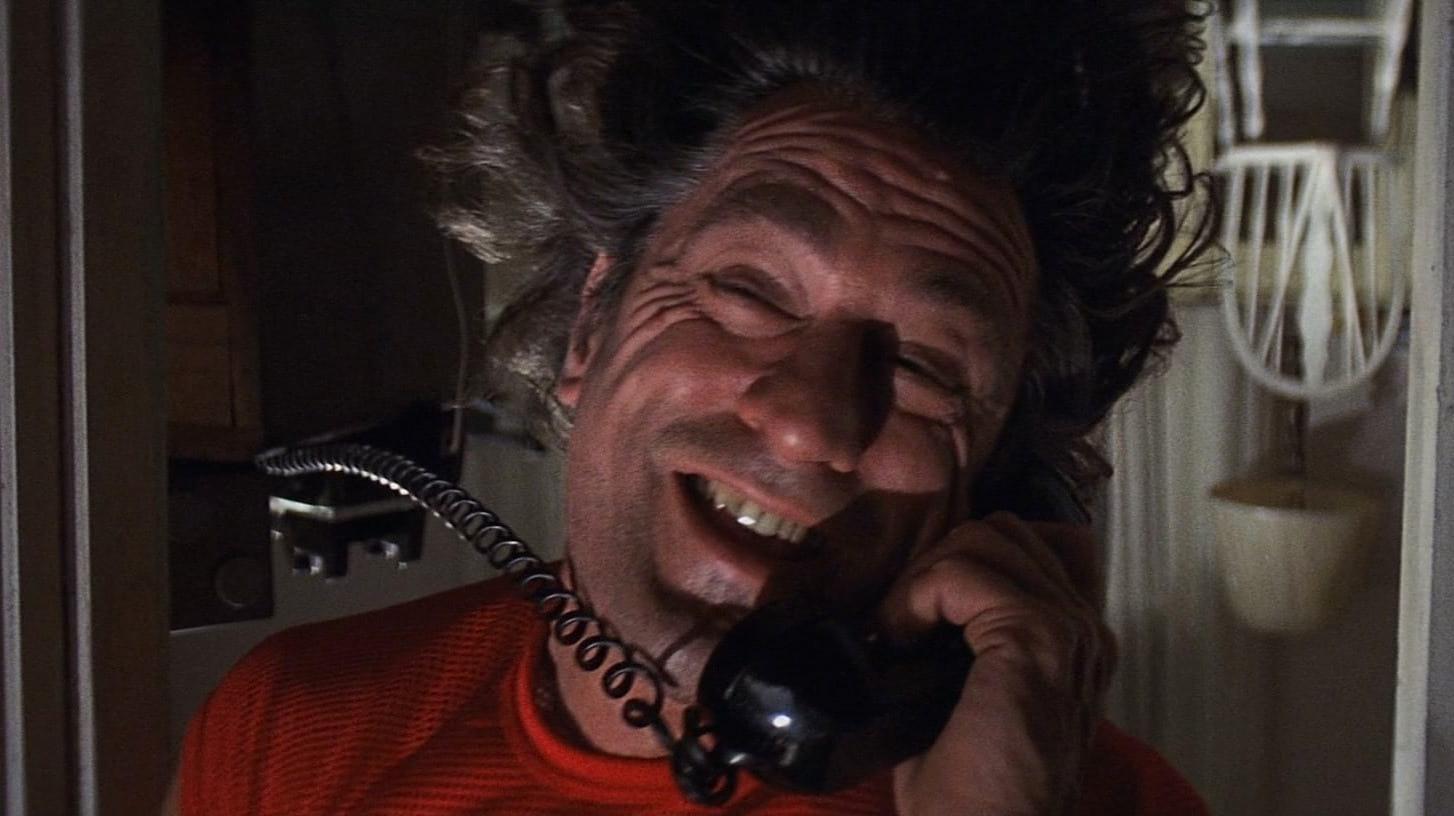

Richardson and Stone continued their already-legendary collaboration on The Doors and JFK (Feb. ’92), and the latter introduced what would become their signature visual approach to subsequent projects — mixing myriad formats, lens types, color and black-and-white emulsions, lighting techniques, and special lab processes — to render a pivotal moment in American history. This was employed to even more disturbing effect in Natural Born Killers (Nov. ’94), and the duo rounded out the decade with Heaven & Earth (Feb. ’94), Nixon (March ’96) and U Turn (Oct. ’97).

Richardson was initially reluctant to collaborate with Stone on Natural Born Killers due to the ultraviolent nature of the script — co-written by Richard Rutkowski, David Veloz and, ironically enough, Richardson’s future collaborator Quentin Tarantino, for whom he has since shot six features [starting with 2003's Kill Bill Vol. 1]. “[Bob] was in a strange place on this movie,” Stone told Pizzello. “I was in the middle of a divorce, so I was in a very difficult place myself. I felt like he was abandoning me, and I asked him to stay on because I was feeling very vulnerable. He did not like the material in its scripted form. As far as the morality of the story was concerned, I argued with him that it represented the culture we were in, and that the picture was a satire, which required us to exaggerate and distort in order to make our point.”

An equally candid Richardson conceded, “I only agreed to do this film out of love for Oliver and our relationship; he’s like an older brother. But once I began the process, it truly became a nightmare for me. Making this movie was like reading Jung’s Modern Man in Search of a Soul. The story brought up unpleasant memories from my own childhood, and those memories plagued me to such a degree that my nights were literally sleepless.”

AC thoroughly dissected James Cameron’s work with articles about Terminator 2: Judgment Day (photographed by Adam Greenberg, ASC; July ’91), True Lies (Russell Carpenter, ASC; Sept. ’94), the large-format special-venue film T2 3-D: Battle Across Time (Carpenter and Peter Anderson, ASC; Aug. ’96) and the box-office phenomenon Titanic (also Carpenter, Dec. ’97).

Discussing one of his main tactics on Titanic with AC staffer Williams, Cameron revealed how it impacted the film’s most iconic shot, in which Jack (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Rose (Kate Winslet) embrace on the bow of the ship: “Our approach to the film was to try to present, in human terms, an event that is far outside human scale. Therefore, there were only a few times when I wanted to do the big wide shots of crowds on the decks to show the greater story that was happening. I instead tried to start on a wide shot, come sweeping in on a recognizable character, and then punch in closer. That way, we’d always have a human connection. I also thought it was important to know where people were geographically, so a lot of the wide shots evolved into closer shots. This, of course, was a photographic approach that hadn’t been used on any previous Titanic films, because they didn’t have a big enough set or the visual effects to back them up. The shots that interested me the most were the ones where you saw the ship and understood its size and then came closer for a specific piece of dramatic action.

“This idea was used most importantly for a scene in which Jack and Rose are embracing at the bow of the ship. They start out as two tiny dots only a few pixels high, relative to this monstrous ship coming toward the camera, and we sweep right up to them into a pretty tight shot.”

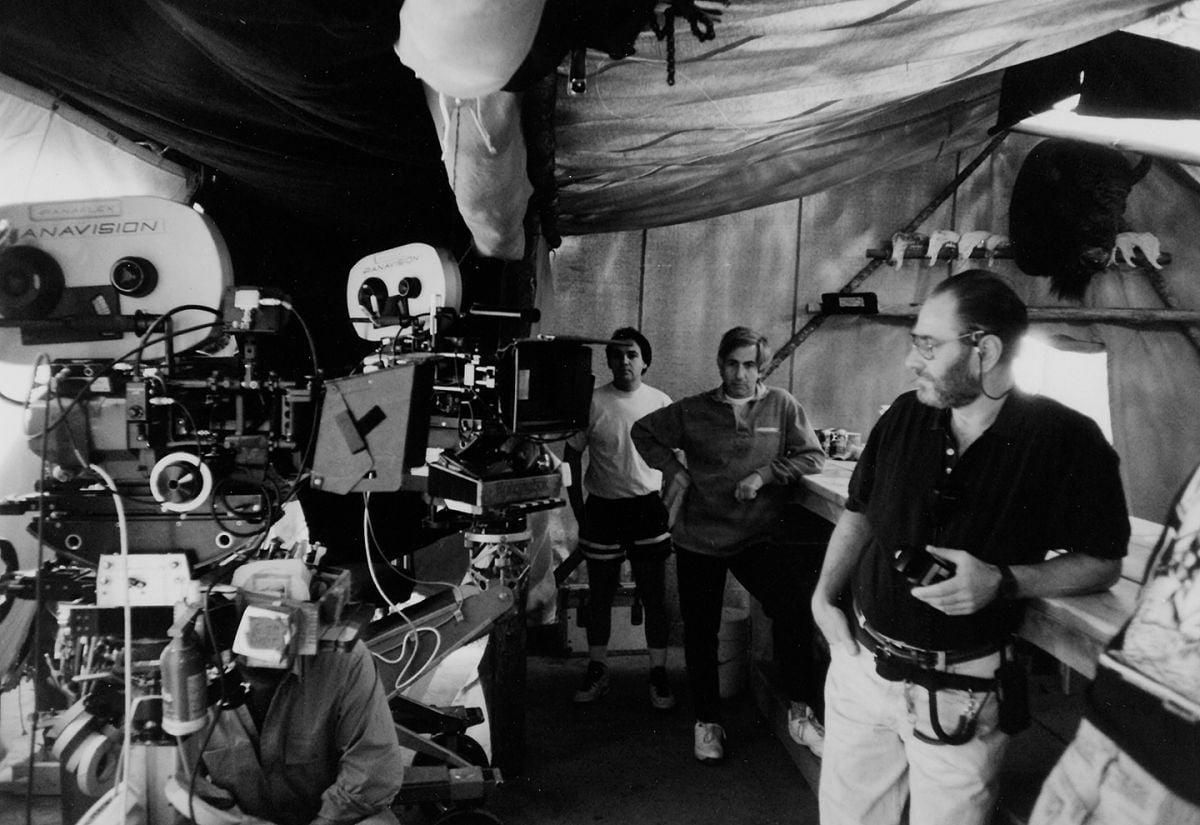

Another collaboration is that of Joel and Ethan Coen and Deakins, who began the decade with 1991’s Barton Fink and followed with The Hudsucker Proxy (April ’94) and Fargo (March ’96 — see below). In my article on Fargo, Joel Coen offered, “We always involve Roger very early. Basically, what we do after we finish the script is sit down with him and talk in general terms about how we were thinking about it from a visual point of view. Then, in specific terms, we do a draft of the storyboards with Roger — showing him a preliminary draft of what we were thinking about — and then refine those ideas scene by scene. So he’s involved pretty much right from the beginning. The style of the shooting is worked out between the three of us.”

The decade also gave rise to several new filmmaking voices, such as David Fincher and Quentin Tarantino.

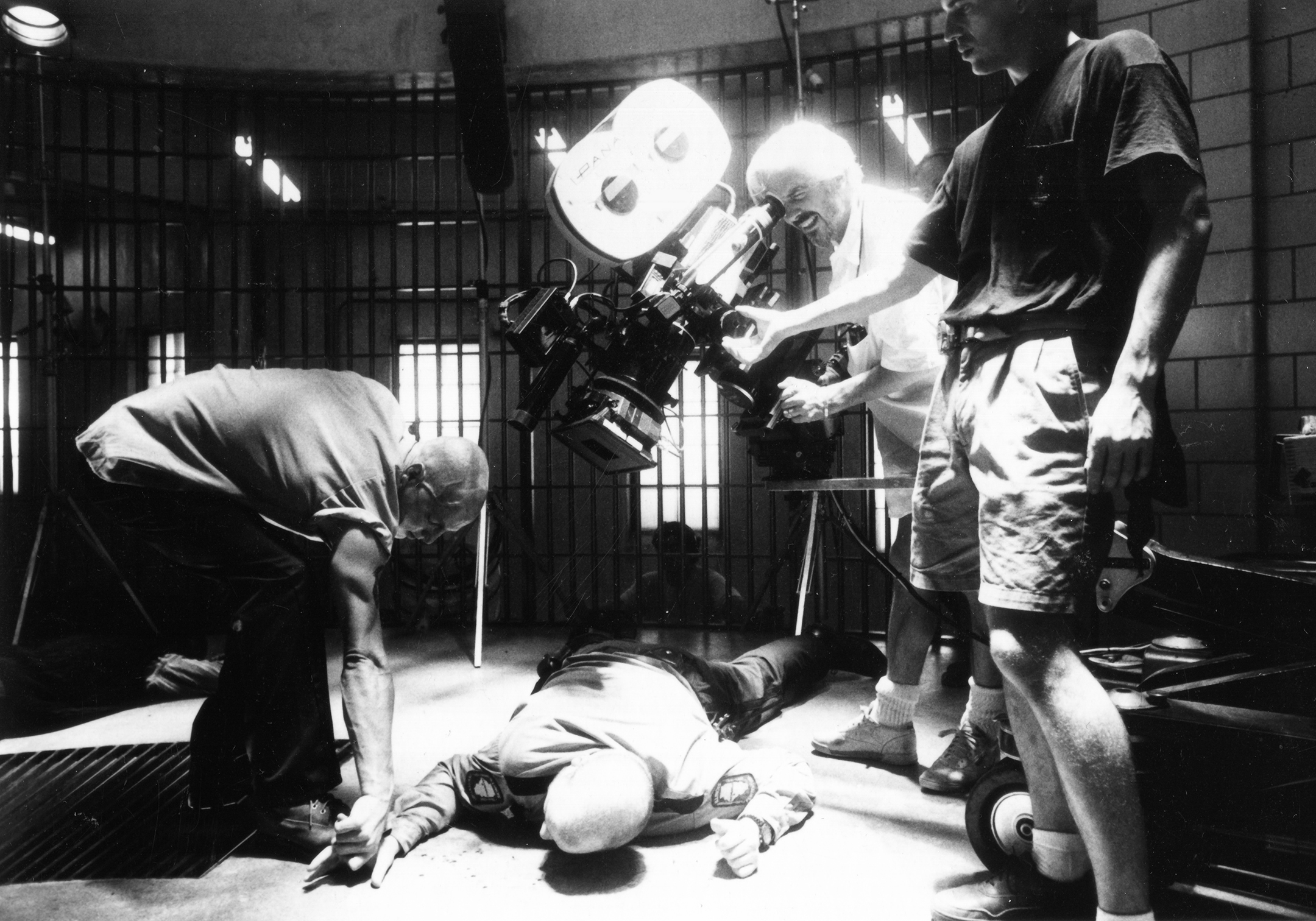

After directing iconic music videos and commercials in the ’80s, Fincher broke into the feature-film realm with Alien3 (July ’92, with VFX coverage in Dec. ’92), a film he began with Jordan Cronenweth, ASC but finished with Alex Thomson, BSC because of Cronenweth’s failing health. Fincher’s next film, Se7en (Oct. ’95), introduced French-Iranian cinematographer Khondji to American audiences, though fans of foreign cinema had already noted his bold choices on Jeunet and Caro’s Delicatessen (1991) and The City of Lost Children (1994).

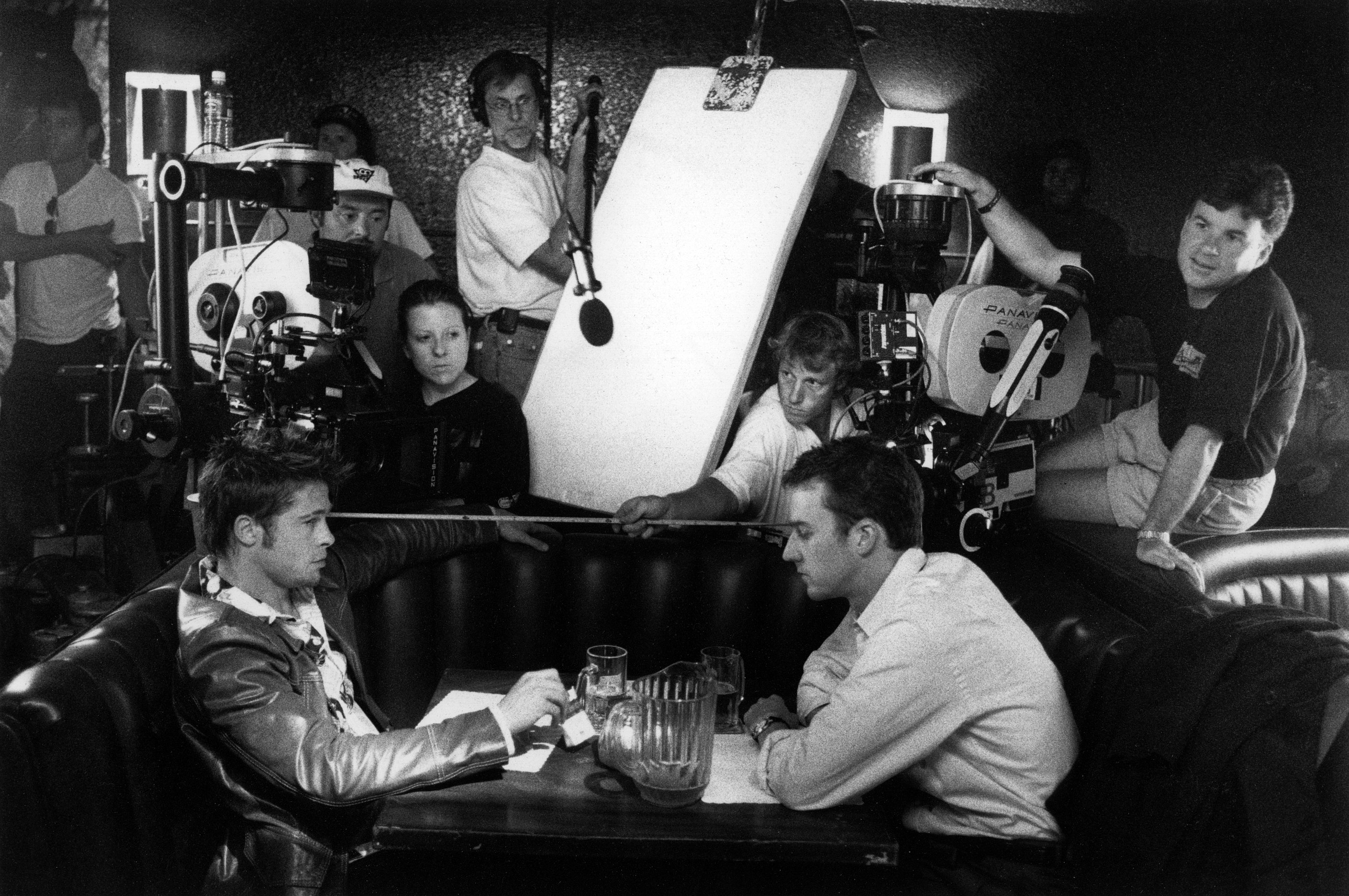

I wrote both of AC’s articles about Fincher’s final films of the decade, The Game (shot by Harris Savides, ASC; Sept. ’97) and Fight Club (the first feature film shot by Jeff Cronenweth, ASC, Jordan’s son; Nov. ’99). “I couldn’t think of a better movie to do as my first film than Fight Club,” Jeff said. “Although I knew it would be rough, I had so much trust in David as a filmmaker that I had the confidence to do the film. He has such a distinct eye and is such a talented storyteller that the visuals in his films are always a collaboration in the truest sense. His knowledge of the medium allows a [cinematographer] to go to places that other directors would either be afraid of or not understand.”

The Western’s resurgence in the ’90s was perhaps best exemplified by the worldwide success of 1990’s Dances With Wolves, directed by Kevin Costner and photographed by Dean Semler, ASC, ACS. Wolves would go on to win seven Oscars, including those for Best Picture, Directing and Cinematography.

Subsequent Westerns released that decade included Black Robe, directed by Bruce Beresford and photographed by Peter James, ASC, ACS (Jan. ’92); Unforgiven, directed by Clint Eastwood and shot by Jack Green, ASC; The Last of the Mohicans, directed by Michael Mann and shot by Dante Spinotti, ASC, AIC (Dec. ’92); and two retellings of the O.K. Corral skirmish, Tombstone (directed by George P. Cosmatos and shot by William A. Fraker, ASC, BSC) and Wyatt Earp, directed by Lawrence Kasdan and shot by Owen Roizman, ASC (June ’94). John Toll, ASC won his first Oscar for Edward Zwick’s frontier drama Legends of the Fall (March ’95), and Spinotti’s gravity-defying camerawork enlivened Sam Raimi’s Spaghetti Western homage The Quick and the Dead (1995). Closing out the decade was Barry Sonnenfeld’s Wild Wild West, shot by Ballhaus (July ’99).

With the end of the 20th century in sight, the decade also saw a proliferation of doomsday fare and disaster films, including Roland Emmerich’s Independence Day, shot by Karl Walter Lindenlaub, ASC, BVK (July ’96); Michael Bay’s Armageddon, shot by John Schwartzman, ASC (July ’98); Jan de Bont’s Twister, shot by Green (May ’96); Tim Burton’s comedic Mars Attacks!, shot by Peter Suschitzky, ASC (Dec. ’96), and Emmerich’s Godzilla, shot by Ueli Steiger, ASC (June ’98). Independent film made its mark in the ’90s, notably with Tarantino’s critically lauded festival darling Reservoir Dogs, shot on low-ISO daylight negative by Andrzej Sekula (Nov. ’92).

The director and cinematographer re-teamed on Pulp Fiction, which cemented Tarantino’s status as a new auteur, and the director closed out the decade with Jackie Brown, shot by Guillermo Navarro, ASC (Jan. ’98). Although Reservoir Dogs launched Tarantino to prominence, he felt obliged to deflect one of the primary criticisms leveled at the film by violence-averse reviewers, telling Pizzello, “Saying you don’t like violence in movies is like saying you don’t like tap-dancing sequences in movies. It’s just one of the many things movies can do. You may not like it, but to suggest that it shouldn’t be in the film is ridiculous; that’s artistic handcuffs. If you go to a comedy, you remember that you laughed and had a good time, as opposed to Reservoir Dogs, where you feel like you’ve been hit in the head with a gun butt for two hours.”

Reflecting upon the effect the movie’s success was having on his career, Tarantino added, “Reservoir Dogs has brought me a lot of attention, and I’m somewhat surprised. I’ve gone from a guy looking at others with hungry eyes to being in American Cinematographer! Success can be frustrating, though; I get a lot of offers for pictures I’d love to do, except now there are conflicts. But I’m not complaining! Sometimes I just sit down and think, ‘God I am bloody lucky.’”

After taking an extended hiatus from feature films for much of the ’80s, Conrad L. Hall, ASC returned to form in the ’90s, eliciting gasps of awe from cinematographers worldwide for his work on Steven Zaillian’s Searching for Bobby Fischer (Feb. ’94) and then crafting innovative looks and moods for Bruce Robinson’s Jennifer 8 (Oct. ’92), Warren Beatty’s Love Affair, Robert Towne’s Without Limits (Sept. ’98) and Zaillian’s A Civil Action (Jan. and June ’99).

The decade also heralded emerging talent like Bill Pope, who essentially crafted an entirely new cinematographic vocabulary with the bullet-time technique of the Wachowskis’ The Matrix (April ’99). Pope’s ’90s trajectory included the Wachowskis’ first feature, Bound, as well as Sam Raimi’s Darkman and Army of Darkness, Amy Heckerling’s Clueless and Vondie Curtis-Hall’s Gridlock’d. “Our main goal with The Matrix was to make an intellectual action movie,” said Larry (now Lana) Wachowski. “We like action movies, guns and kung fu, but we’re tired of assembly-line action movies that are devoid of any intellectual content. We were determined to put as many ideas into the movie as we could, and purposefully set out to try to put images up on the screen that people haven’t ever seen before.”

Pope recalled, “[The Wachowskis] had seen and loved [the 1993 horror-fantasy film] Army of Darkness, which I shot for director Sam Raimi. They called me in, and we had a terrific meeting. I think they hired me because I read comics and knew what they were talking about whenever they mentioned a particular title. In fact, during our meeting, there was a copy of Frank Miller’s Sin City on their desk, so I asked, ‘Is that what you want the film to look like?’ We were all impressed by Miller’s use of high-contrast, jet-black areas in the frame to focus the eye, and his extreme stylization of reality. I had long wanted to do something that stylized on film.”

To capture the movie’s famous “bullet-time” slow-motion action sequences, visual-effects supervisor John Gaeta and his team employed up to 120 still cameras used to sequentially capture the actors’ high-velocity movements. The filmmakers used a custom laser-guided tracking system to ensure that each of the cameras would be aimed at the right “interest point” during a given sequence. “Much of what’s been done to date with the array technique has involved ‘freezing’ objects in the middle of a circle, where it’s much easier to physically line the cameras up to capture the action since it’s fixed on one little place,” Gaeta observed. “We upped the ante even further by capturing stunts that wavered all over the place. When the actors jumped across the room, we wanted to do a really dynamic crane shot that boomed up over their heads and tracked the guys through the entire stunt.”

Other ASC cinematographers for whom the ’90s were especially fruitful included Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, HSC, whose AC coverage included Maverick (Nov. ’94), Assassins (Nov. ’95), The Ghost and the Darkness (Nov. ’96) and Playing by Heart (Dec. ’98); Allen Daviau, ASC, who sat down with the magazine to discuss Avalon (Oct. ’90), Bugsy (Nov. ’91) and Fearless (Nov. ’93); Stephen H. Burum, ASC, whose AC coverage included He Said, She Said (April ’91), The Shadow (July ’94), Mission: Impossible (June ’96) and Snake Eyes (Aug. ’98); and Roizman, who was interviewed about I Love You to Death (April ’90), Grand Canyon (Nov. ’91) and Wyatt Earp (June ’94).

The decade also saw Hollywood hark back to the roadshow spectacle of yore by briefly resurrecting 70mm exhibition. Ron Howard’s Far and Away was photographed with newly fabricated Panavision System 65 cameras by Mikael Salomon, ASC (June ’92), and British cinematographer Alex Thomson, BSC utilized 65mm for Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet (Jan. ’97).

AC adopted a new practice in the mid-1990s: covering films nominated for ASC and/or Academy Awards that had not been covered during their theatrical exhibition. I inaugurated the practice in the June ’95 issue with short features about Deakins’ ASC-and Oscar-nominated work on Frank Darabont’s The Shawshank Redemption and Toll’s ASC-and Oscar-winning work on Mel Gibson’s Braveheart. In this same vein the following year, in June ’96, we covered Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki, ASC, AMC for Alfonso Cuarón’s A Little Princess and Dariusz Wolski, ASC for Tony Scott’s Crimson Tide.

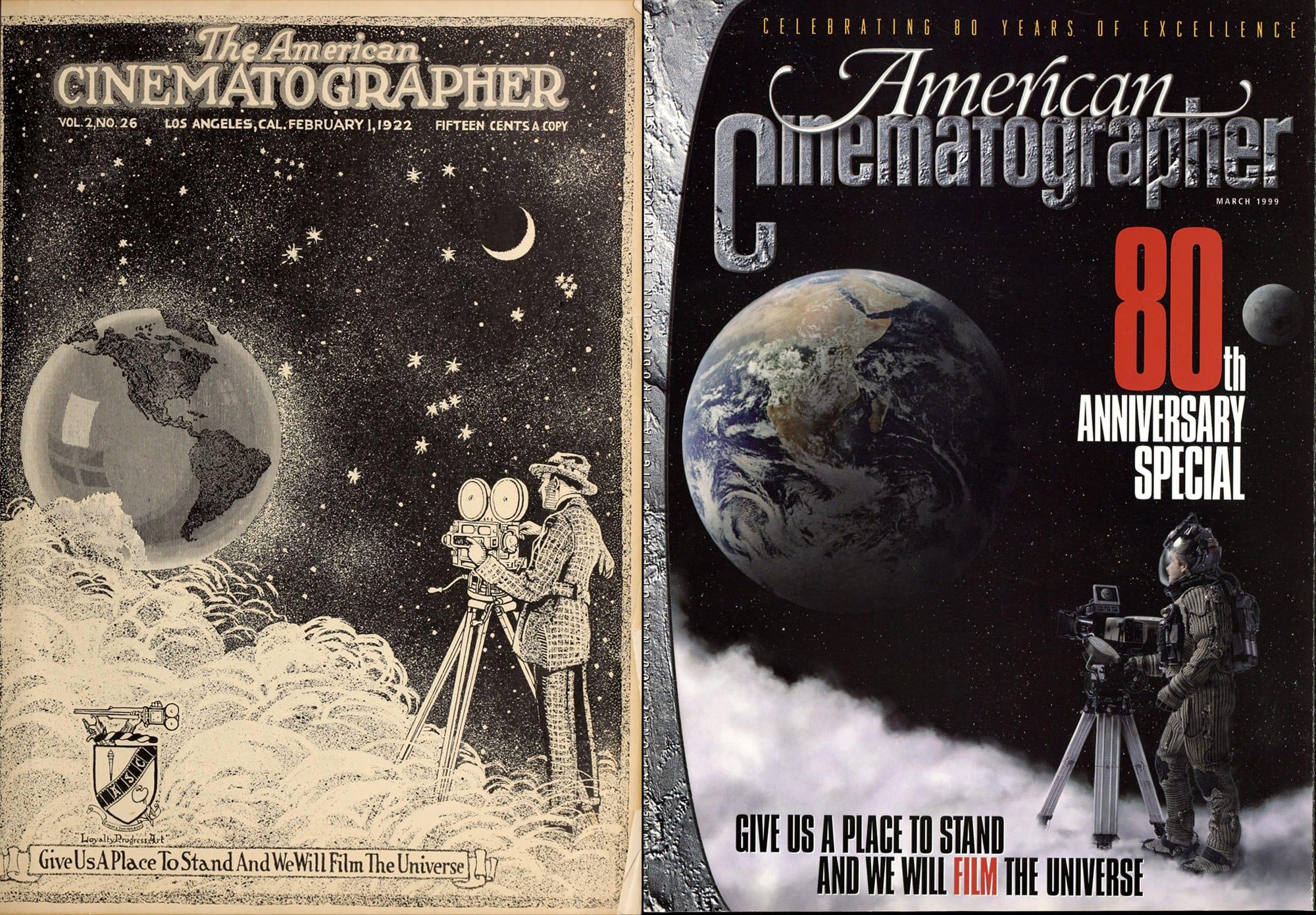

The magazine experienced other noteworthy milestones in the decade as well. The July 1995 issue saw the promotion of Pizzello to executive editor; the January 1998 issue marked a significant redesign of the magazine, with Amistad gracing the cover in its new format; and March 1999 was a special double issue (232 pages) celebrating the ASC’s 80th anniversary.

The issue’s cover was a recreation of a 1922 cover illustration that showed a cinematographer filming the Earth from above the celestial clouds and featured the motto, “Give us a place to stand and we will film the universe.” For the 1999 update, Williams, then AC’s associate editor (who now serves as the magazine’s web director and associate publisher), posed as the intrepid, space-suited cinematographer.

Ever since video was invented, the same question has always come up: How can we make this look like film? This possibility was one of the things we were most interested in testing. I am, however, beginning to believe that making video look like film is not ultimately desirable — that these are two separate mediums and should be thought of as such. There is a need for both styles, and the two can definitely work side by side without one trying to dominate the other.

Motion-picture images, shot at 24 frames per second, have an elusive quality when viewed by projecting the film on a screen or when electronically transferred to 30-frames-per-second video using a flying-spot scanning system. This quality is almost impossible to duplicate using any other type of imaging system. Even film shot at 30 fps for direct transfer to video loses much of this “artistic look.” Dramatic or narrative productions, as opposed to real events, need to be presented in such a way that some visual information is left up to the imagination. If this condition is not present, the image conveys a more immediate quality and doesn’t allow the viewer the ability to use imagination in following the storyline. A similar difference exists between radio or audio drama and visual drama. Telling a story with sound [alone] allows the audience members to completely use their imaginations to create the images in their minds. Standard 24-frame motion picture still allows for the perception of some of this mystery.

From “Fielding the Dream: HDTV’s Tryout,”

by Steven B. Poster, ASC (AC Aug. ’91)

“Steven has always employed a certain mood, or those ‘Spielberg touches,’ but this movie has a completely different style than his previous films. Schindler’s List was shot in a very crude technical manner. We were kind of aiming toward imperfection, little so-called ‘flaws’ that might be considered mistakes, such as handheld shots in scenes that would normally be shot on the dolly. Often we would set up the Pee Wee dolly and then have the operator, Raymond Stella, hand-hold while sitting on the dolly seat.

“I approached this movie as if I had to photograph it 50 years ago … How would I do it? Naturally, a lot of it would be set on the ground where the camera was not level. We weren’t making dutch angles and shots like that; that was not the purpose. It was simply more real to have certain imperfections in the camera movement, or soft images. All those elements will add to the emotional side of the movie. When people go to see this movie and expect to see a Steven Spielberg blockbuster, they will find something else — a dark and unobtrusive tone.”

From “Schindler’s List Finds Heroism Amid Holocaust,”

by Karen Erbach (AC Jan. ’94)

Asked why he is so drawn to mob-related subject matter, Scorsese muses, “I find these types of stories inherently dramatic. Even the ancient Greek playwrights always said that the antagonist is more interesting than the protagonist. Let’s face it, the bad guy is more interesting than the good guy! My attraction to this material also goes back to where I grew up, and being familiar with a certain kind of lifestyle. When I was 8 or 9, I saw that lifestyle around me in the streets, and I recognized it as another, more rebellious way of living, rather than settling into the norm or the mainstream.

“That’s a pretty big subject,” he asserts. “I find these characters and their lives to be almost a microcosm of the outside world of politics, government, and so on. It’s like the old line from The Threepenny Opera, when Mack the Knife makes a speech as he is about to be hanged. He asks the people, ‘Why are you hanging me? Ultimately, what’s the robbing of the bank to the founding of a bank?’”

From Casino article “Ace in the Hole,”

by Stephen Pizzello (AC Nov. ’95)

When AC assigned me to cover Fargo for the March 1996 issue, I was particularly excited when I was informed that the Coen brothers, known for their reluctance to speak with journalists, were willing to discuss the contributions of their frequent partner-in-crime, Roger Deakins [ASC, BSC]. In preparing for my interview with the directors, I purchased the published screenplay edition of Barton Fink/Miller’s Crossing at Book Soup in Los Angeles.

The book featured a foreword by the Coens’ longtime editor, Roderick Jaynes, who proceeded to eviscerate the brothers for their infuriating shooting method and the dearth of coverage it yielded. When I spoke to the Coens by phone, I mentioned this curious editorial, only to hear a cackle of laughter from both of them. They explained that “Jaynes” was a fabrication, a fictitious name created for the editing credit on their films, which the brothers actually cut themselves. However, I didn’t feel quite as foolish when Jaynes received an Academy Award nomination for editing Fargo!

— Christopher Probst

American Cinematographer: Do you think the relationships between directors and cinematographers is going to change in the digital age? For example, will it still be important to light the actors and the sets properly, and to get everything just right [at the moment of capture]?

Lucas: Oh yeah! The camera’s still extremely important. It’s just that now, there are a lot more resources available to fix things if they aren’t quite right, to extend “magic hour” if you want to, or to design the look of the film more meticulously than before. As [cinematographers] get more into the digital age, they will find that the essence of what they do — which is to frame a shot and to make sure the lighting is beautiful or appropriate — will always remain the same.

But it seems that framing and other techniques won’t matter as much, because you can alter those things later on if you want.

Lucas: You can alter them, but somebody has to decide what that framing is going to be, and the art of the frame still has to be determined … Aesthetic decisions still have to be made, and the fact that you can change things later just gives you more freedom. You can come back the next day and say, ‘After seeing the sequence, I think we would have been better off if we were in 10 percent [closer] on this shot.’ Or, if you want to pull back or move the characters over a little bit, you can rearrange things. Movies are shot in an unlimited number of impossible conditions, and you don’t always have the control over the situation that you’d hoped to have. Sometimes people don’t quite hit their marks, or the lighting isn’t quite right, or you have two or three cameras and one of them wasn’t framed up like you thought it was when you walked away from it. Now you can adjust all of that, and you don’t have to live with mistakes.

From “Master of His Universe,” an interview on

Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace

by Ron Magid (AC Sept. ’99)

During the 1990s, achievements by talented female cinematographers were covered in articles detailing productions shot by Maryse Alberti (Incident at Oglala, Crumb, When We Were Kings, Velvet Goldmine), Christine Choy (My America … or Honk if You Love Buddha), Roxanne DiSanto (Young Goodman Brown), Sue Gibson, BSC (Mrs. Dalloway), Judy Irola, ASC (An Ambush of Ghosts), Ellen Kuras, ASC (I Shot Andy Warhol, 4 Little Girls, Summer of Sam), Teresa Medina (Female Perversions), Nina Menkes (The Bloody Child), Claudia Raschke (The Last Good Time, No Way Home), Tami Reiker, ASC (High Art), Lisa Rinzler (Dead Presidents, Three Seasons), Nancy Schreiber, ASC (Visions of Light, Nevada, Your Friends & Neighbors), Sandi Sissel, ASC, ACS (Camp Nowhere), Mandy Walker, ASC, ACS (The Well) and Lisa Wiegand, ASC (Shopping for Fangs).