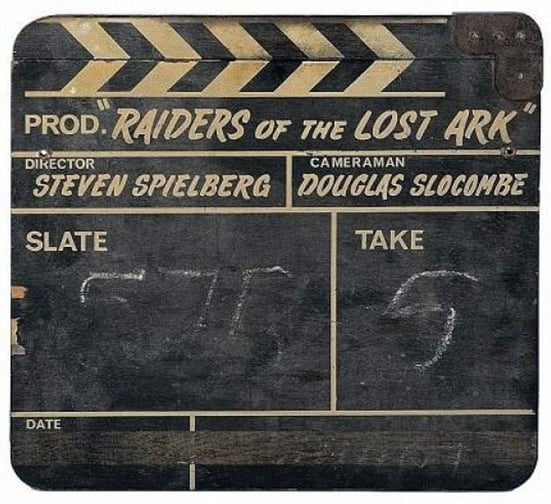

Of Narrow Misses and Close Calls: Raiders of the Lost Ark — Directing

Homage to a galaxy of Saturday matinee serial stars and their derring-do inspires a wild adventure flick with nonstop action all the way through.

By Steven Spielberg

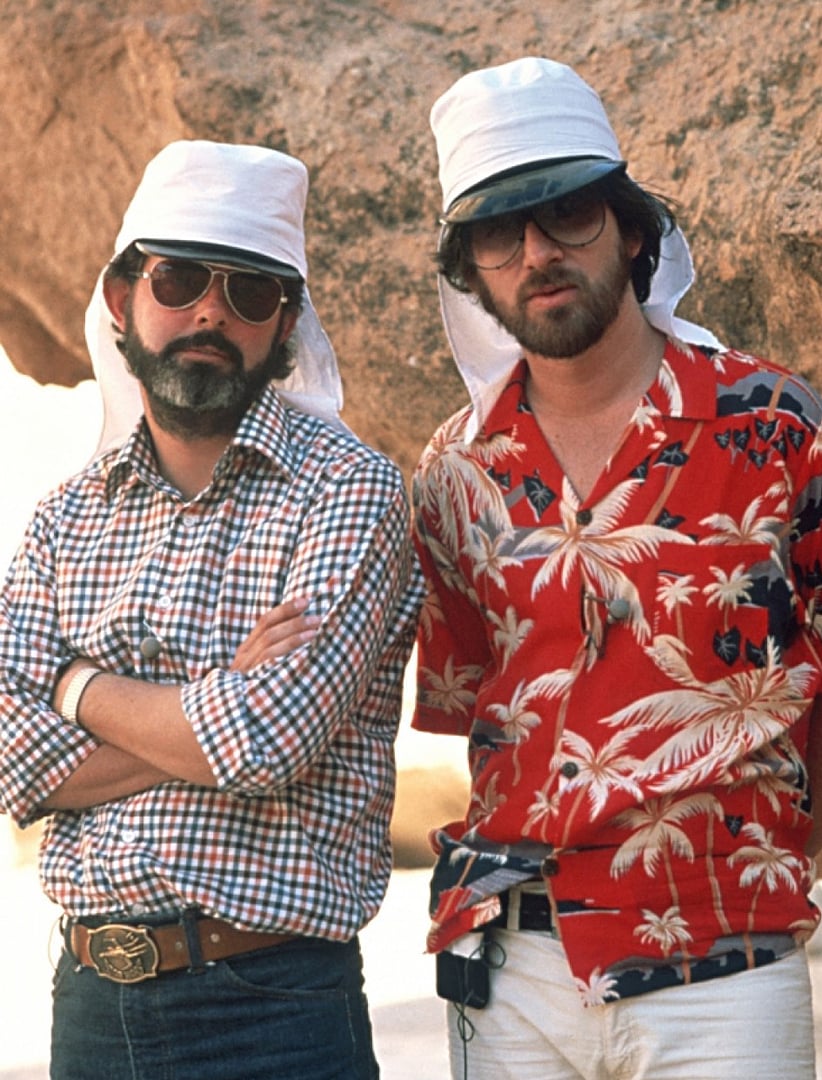

The project which eventually ended up on the screen as Raiders of the Lost Ark began with George Lucas in the early 1970s. As I understand it, he got two ideas very close together: Star Wars and Raiders. He was going to make one or the other at the time and decided to make Star Wars first.

George and I happened to be in Hawaii at the same time in May of 1977. Star Wars had just opened and George came back from the telephone, having discovered that the film, in the first weekend of its initial limited run, was a big hit.

Then he told me the story, as if to say, “... and for my next number, I'm going to…” so began Raiders of the Lost Ark.

He told me he wanted to make a movie about an archaeologist who was also an adventuring soldier of fortune, Indiana Jones, and his pursuit of the lost Ark of the Covenant in a race against time and destiny with Hitler's best Nazi archaeologists. I told George sometime before this that I had always wanted to make a James Bond-style adventure thriller and he said, "I got something very similar to what you would like to do." Sure enough, there were all the "Bonding" elements, but without the hardware and the gimmickry, which is what appealed to me.

During that fateful encounter on the beach (while we were building a monumental sand castle), George finished telling me the basic elements of the story, and my tongue was hanging out when he dropped a bomb by informing me that the film was probably going to be directed by Phil Kaufman who had helped him initially with a few elements of the story. George asked me to hold my breath and he would check with Phil and see if Phil was going to give it up for something else and, sure enough, some months later George called me and said, "Are you still interested in that movie I told you about in Hawaii, because Phil isn't going to do it now?" I said, "Yes, I am, certainly." We sat down and George suggested that I select the writer. I just convinced Universal to purchase a script for me called Continental Divide by a new writer I discovered named Larry Kasdan, who had only written one screenplay prior to that called The Bodyguard. When I got Universal to buy the script — at the time, for me to produce and direct — I brought Larry in to meet George. I was very impressed with Larry, and I said, "I'd like Larry to write Raiders."

George read Continental Divide over the weekend, and on Monday we all had a meeting with George and I offered him the job. Larry began working on Raiders and, in four or five months, came back with a wonderful, but overly long first-draft screenplay. Several months after that, George and Larry did some private work on it and George helped to streamline and cut it down to a suitable length and then it was turned over to me and I began making the movie. That was in December of 1979, when I officially started on it. We began shooting in June of 1980 and finished in September 1980. It was actually the shortest schedule of completion that I've been involved with since The Sugarland Express. Sugarland took 55 days. Raiders, for all of its spectacle and expansiveness, we shot in 73 days, which I'm quite proud of.

I had grown up with serials. There was a revival theater near my house in Phoenix, Arizona, the Kiva Theater, and on Saturdays they would show a double feature and sandwich in between 10 cartoons, previews of coming attractions from 20 years past, and usually two serials. Every Saturday I would go there and I would see these old revival movies and these old revival series: Tailspin Tommy, and Masked Marvel, Spy Smasher, Don Winslow of the Navy, Commander Cody — and I always wondered why Hollywood hadn't done anything to revive the genre of the outdoor adventure; of narrow misses and close calls. It was just amazing to me that it hadn't been done before.

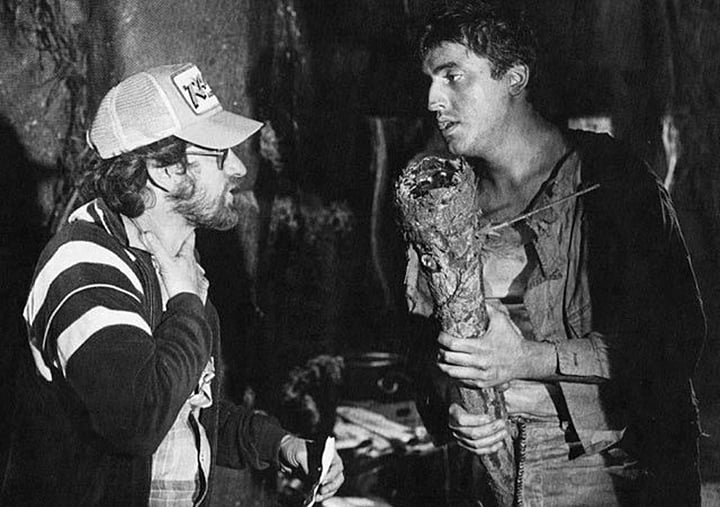

When I sat down to make the movie, George, as executive producer, was very true to form, as with Irwin Kershner on The Empire Strikes Back and Bill Norton on More American Graffiti, in the sense that he believes that a director directs and an executive producer compliments the team with positive reinforcement and George was wonderful at that.

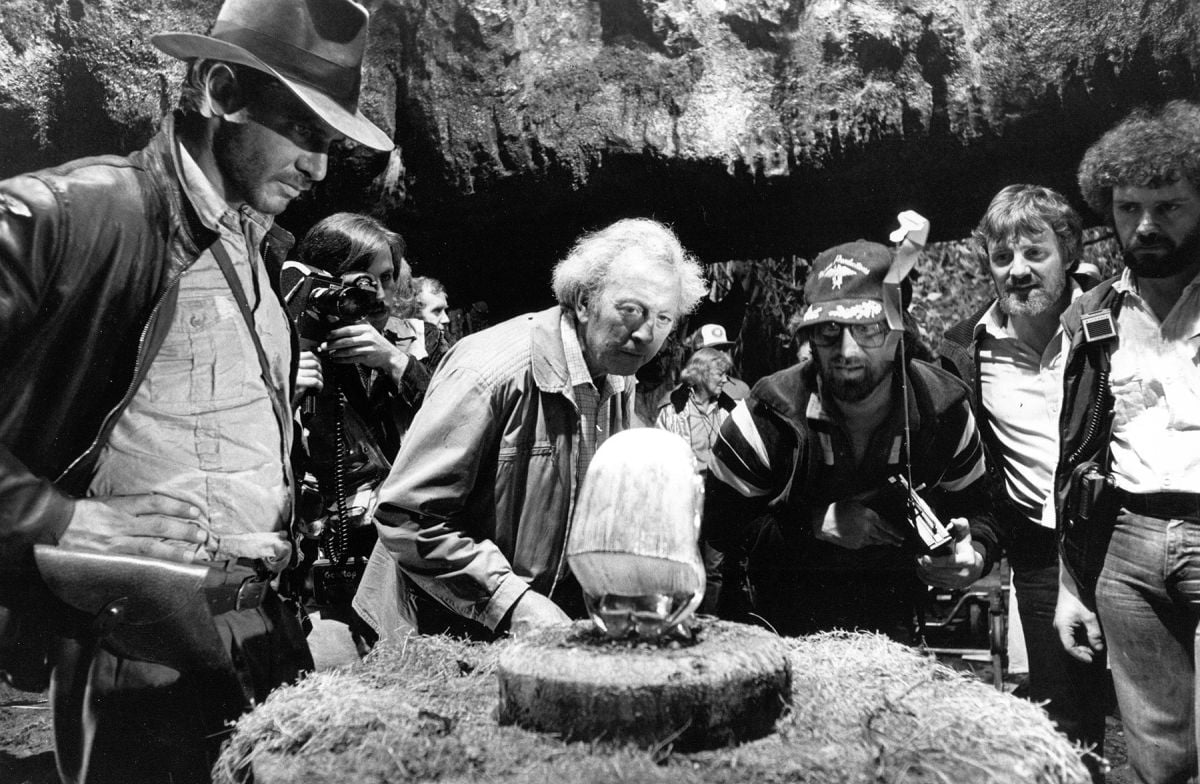

My first choice as director of photography, of course, and the first person I hired, was Douglas Slocombe [BSC]. Having worked with Douglas for the two weeks of prep and shooting on the Close Encounters India sequence, I met camera operator Chic Waterson and assistant cameraman Robin Vidgeon and Dougie in India for the first time, and that's quite a place to get to know somebody. We sort of gave each other shelter from the culture shock of working on the outskirts of India and got to know each other very well over the 12 days that we were there.

“When I went to England on my first ‘recce’ I discovered a well-oiled Star Wars machine of technicians and artisans who have been working on the Star Wars series now since 1976.”

Afterwards I told Dougie that I really wanted to work with him on a complete feature and I'm sure that he thought I was just another Hollywood director blowing Yankee smoke up the British Union Jack, so three years later he was very surprised to hear from me.

Of course, the second person rounded up was Michael Kahn, who edited 1941 and Close Encounters, plus two films I had executive produced: Used Cars and Poltergeist. Michael had been with me for five years now and is a remarkable collaborator.

I had always wanted to work with production designer Norman Reynolds who, coincidentally, just finished with George on Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back. George suggested Robert Watts, who had been with him for a long time, to be the production manager and associate producer.

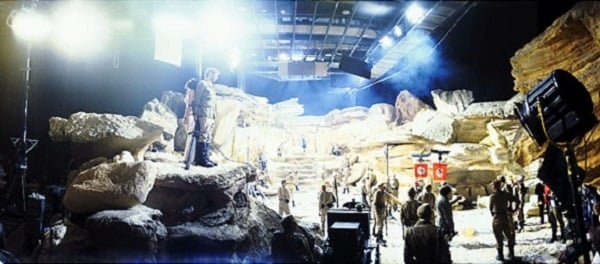

When I went to England on my first “recce” I discovered a well-oiled Star Wars machine of technicians and artisans who have been working on the Star Wars series now since 1976. They were very used to working together and we all, in concert, decided to get the same team that made Star Wars, The Empire Strikes Back and also, by coincidence, Superman. They were very accustomed to difficult locations, spectacular sets and eccentric special effects, so it came as no surprise to them when they first heard news that the script was going to take place in four countries on three continents with seven massive scenic structures and many physical and optical special effects. They had been there before.

Every movie has surprises. You can make all the Jaws and Star Wars in the world, but every special effects movie has something in it that teaches you something you probably wouldn't want to do again. I keep saying to myself, after I finish a massive production, that I’m going to make my “little movie,” and I never have. I said it after Sugarland Express, which was massive in its day and its own scale. After Jaws, I said I would never go underwater and work with anything with pneumatics or hydraulics; and after Close Encounters I said, "That's it with 70mm and optical effects and matte paintings." After 1941 I said, “No more miniatures and no more multiple storylines.” And I wound up smack dab in the middle of it again with Raiders of the Lost Ark.

I really wanted to make Raiders economically and make it look like $40 million and, in fact, spend only $20 million — which was the original intended budget. The $20 million actually would pay for 87 days of shooting, but I had devised a second schedule of 73 days that very few people knew about — Paramount Pictures, for one.

That was the schedule that we ultimately met. I just found that, by not doing 15 takes on each shot, but by doing only, let's say, three to five takes, I was able to get a lot more spontaneity into the film with less self-indulgence and pretentiousness. I didn't have a lot of time to try different things, but I think I've made enough movies that involved horrendous logistics — Jaws, Close Encounters and 1941 — for me to finally receive my diploma, graduate with both honor and infamy, and get into the field where I can make a movie responsibly for a relatively medium budget that would appear to be something more expensive.

That was the challenge. That and, of course, trying to make a movie that would just rock your chairs at the steering bolts. I've always enjoyed flash and I always felt that if I could shoot Raiders quickly, there would be an implicit energy throughout the film and that, in fact, is what happened.

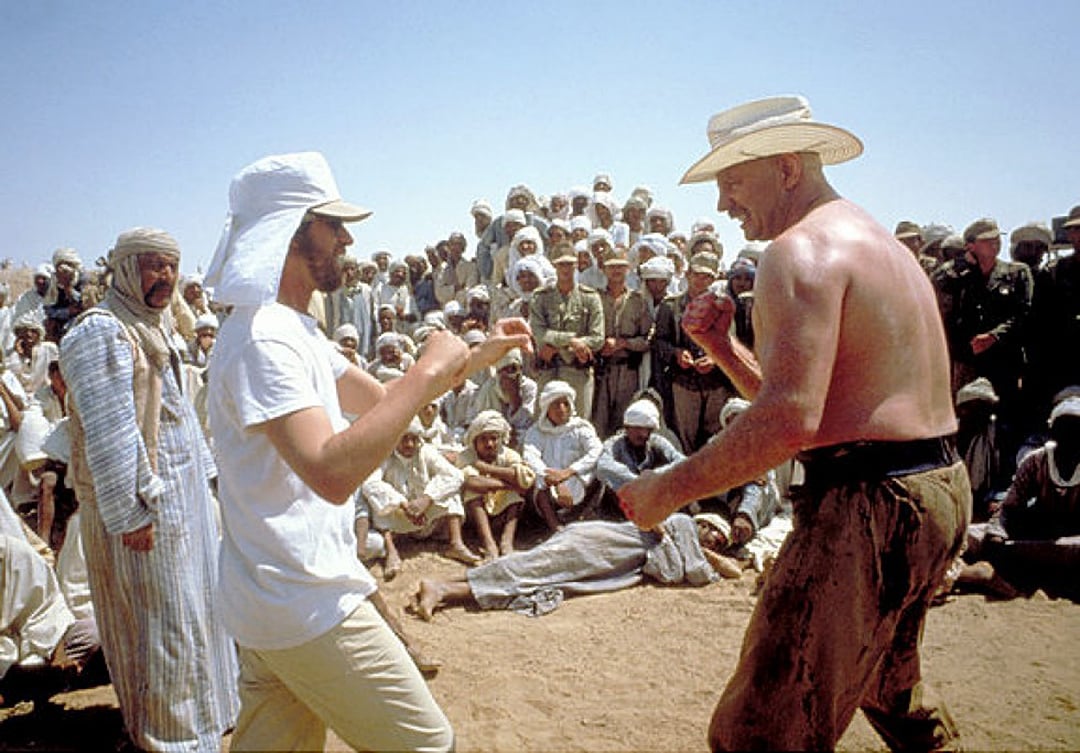

My girlfriend came down and spent a few days in Tunisia. She came at a time when we were averaging 35 setups a day, outside. She was just amazed that movies were made that way. I explained to her that this is the way they used to make movies in the silent days when they had a camera and a tripod with a crank and they would virtually put the camera down and start cranking and the minute they got what they needed, and no more, the camera would come out of the ground and go to the next position, where the cranking would resume.

It was virtually a relay race to accomplish as many exciting setups as possible before sundown made us stop shooting. And also to get the hell out of there, because none of us liked it there. It was the least enjoyable location I think I've ever experienced. The desert was a furnace and some of the local food put a majority of the group through gastric agony. George had enjoyed working there on Star Wars, but that was before the Tunisian government became film conscious and before they realized that there was big foreign potential for outside movies inside North Africa.

Everybody worked very quickly. They just ran around. Dougie Slocombe, who is in his mid-sixties, ran faster than everybody. When I said, "I'd like the third camera on the hill" — I'd turn around and Dougie would be on the hill with a third camera two minutes after I had spoken. I found that rather amazing. Dougie would walk around — he's never fallen off a cliff or off of a camera car — but throughout the shooting of Raiders of the Lost Ark there were dozens of cliffhangers all involving Dougie Slocombe and a sense of balance. Dougie would have his eye screwed into his contrast glass, looking up at the sun and the clouds, walking backwards and, sure enough, there would be a 350-foot drop and, sure enough, Robin or Chic, who have worked with Dougie for an average of 25 years as a team, would reach a hand out and keep Dougie from falling into Roadrunner and Coyote oblivion. When Dougie has his eye to the camera, he's in another world. He is in the land of motion picture fantasy and he doesn't realize that he's a mere mortal. He's the perfect audience.

The rest of the company — and I say this as a compliment to the English — never lost their cool, even though the prevailing temperature in the shade of an umbrella was 130 degrees in the Sahara Desert. The only relief came when the wind would pick up at around 4 o'clock in the afternoon and cool the breeze to a mere 110 degrees.

I kept thinking of David Lean, and I think what kept us going was the thought that Lean, at 60, had done this every day for a year. David Lean was our criterion for survival. At least we had hotels in Nefta and Gafsa with air conditioning. David Lean slept in tents during the making of Lawrence of Arabia. They bivouacked right out of the Sahara. And look at Lean's movies. My God, they are spectacular!

Nothing seems, on the surface, to ruffle the British. I'm very used to losing my head and watching everybody else follow, and I felt a little conspicuous jumping up and down and screaming, "We're losing the light! We're losing the light!" The rest of the British crew just sat there looking up at the sun and quite agreeing with me.

“There were certainly some physical problems, like getting that 12-foot boulder to chase Harrison Ford many times, and the flying wing that was built not to fly, but to generate danger with its deadly propeller blades.”

Raiders of the Lost Ark differed in certain ways from any of the other pictures I've made, although there are great similarities in terms of the amount of people who worked on my last four movies and the scale and size of production — which have been rather gargantuan — but technically, it differed because it didn't involve anything that hadn't been done in movies. Nobody had ever made a movie with a 25-foot mechanized shark before Jaws. So, in a way, that was a state-of-the-art movie, in terms of its physical accomplishments on the water, in the actual ocean.

In Close Encounters we generated special optical effects that had not been done before. Only Star Wars, up north in Marin County, was doing it at the same time that we were doing it down south in Hollywood. 1941 contain probably the most painstakingly genuine miniatures ever done in Hollywood and I'm not bragging when I say that I believe it's true that, with the probable exception of In Old Chicago, Raiders was a much more down-to-earth film rooted in something more attainable.

There were certainly some physical problems, like getting that 12-foot boulder to chase Harrison Ford many times, and the flying wing that was built not to fly, but to generate danger with its deadly propeller blades. That was new to me, but Raiders is much more of an earthly adventure and I kept saying, "This is great, but what if this had been on the water?" Then we would laugh and say, "Thank goodness we are doing impossible special effects on land." Another nice result was that the next day I could view the dailies without having to wait six months to see the optical composites.

But Raiders doesn't differ that much from my other large productions, because logistics are logistics and large sets are large sets. It takes longer to light them — more units and electricians — and I'm certainly used to that. And yet, a couple years ago, in an article for American Cinematographer, I said that I never learned anything new after each picture that involved complicated effects, because each situation is a new unexplored territory. I think I can say now, after four of these big monsters, that I have learned a lot, and I've learned so much from the preceding films that Raiders was much easier for me than it would have been in 1973, had this been ahead of Sugarland Express. I would have been in a helpless quandry had it not been for seven years of making movies at hard labor.

I really decided that the only way I could bring this movie in for the budget and on schedule, was to storyboard not only the sequences involving fights and chases, but also the sequences involving behavior, attitudes and dialogue. I wound up having to employ four artists instead of the usual one, starting with Ed Verreaux, who was my principal artist, and Dave Negron and Michael Lloyd and Joe Johnson up at ILM.

It took at least four artists to complete my vision of the movie in the mere four months I had of production design prep. In the interest of saving money, we didn't start prep until very early in 1980, for a June start. Now that's squeezing it pretty tight. I'm used to at least a one-year prep, and I only really had about six months to prepare the picture from production design to casting, through location selection.

“I believe that the photographic style of this movie happened by itself through an interesting compromise between what Dougie loves to do and what I wanted from him.”

By storyboarding everything, I was really able to rely on only 50% of the storyboards for most of the time. What I usually do on most projects is prepare with drawings between 60% and 75% of the film. Yet I won't feel compelled to stick to every board, because I allow the boards to be my fallback design. But if I'm inspired and some divine madness hits me and I think of a better way to do something, I try to be flexible enough to drop the homework and hear the inspiration.

Certainly, with Close Encounters, the whole last 25 minutes of the special effects were storyboarded and I had to stick to the storyboards almost maniacally, because a lot of the elements had been photographed before our production unit arrived in Mobile, Alabama, and certainly a lot of the elements had been shot to fit perfectly into those pre-concepts. So I couldn't do much changing there.

With 1941 there were a lot of changes made because the on-set ideas kept getting better and better. With Raiders, I felt that I needed every storyboard to stay on schedule. I probably stuck to the storyboards on Raiders generally more than I had in other situations, because I really felt that, in my head, I had directed a pretty good movie, way back in January, February, March — and why change it in June, July, August and September? I stuck to a lot of the storyboards, especially involving the truck case which was 100% storyboarded, and Mickey Moore who substantially directed the master shots and the stunt work of the truck chase, pretty much stuck to 85% of the sketches and did a wonderful job. As a matter of fact, on each slate, they would first give the scene number and they would flip the slate around and there would be that sketch to compare it to the actual shot achieved by the second unit. That was a really good way to work. Of course, Mickey, who himself is a very creative individual, made the time to add two or three shots of his own to make the chase even more exciting.

I had never used a second unit director before and I only agreed to use the second unit director for the truck chase because it was a very extensive pursuit and covered a lot of different locations. The second unit began shooting the truck chase a week before we came to Tunisia so they were well into it when we arrived at Nefta. I directed all the sequences involving principals in the truck chase, everything involving Harrison. Everything involving wider shots using doubles, Mickey did. It was really the only way to make the chase exciting without adding an extra 15 days to the 73 I scheduled.

As part of my pre-planning of the visual style of the picture, I would cut out pictures from different glossy color magazines on fashion or art or photography and I would discuss them with Dougie Slocombe — especially in terms of the general look and such elements as cross lighting. I'd say, "Dougie, I’d love to get them against the hot window and let them go real black against it." And he would say, "That's a lovely shot and very attainable." We did that very early on.

“Dougie, more than any cameraman I’ve ever worked with, uses the sun as a key arc light, and lets essentially everything follow its route.”

I originally wanted a much moodier, almost neo-Brechtian style of light and shadow for this film. I wanted the film to resemble more, say The Informer — the film being more film noir than I eventually accomplished. But I found that the movie was beginning to paint itself out of the corner I put it in, by the kind of sketchy brightness which is Dougie's forte and I began to see what Dougie was doing. He was giving it a fuller look, not a flat look; he was giving it a very nice backlit look, but a very full backlit look and because of that he was getting amazing depth of field due to the number of lights he was using. In the dailies, of course, it looks very dark and moody and atmospheric, while on the set it looked very bright, but he was not shooting wide open, to say the least. He was stopping down. So between my original discussions with Dougie about film noir and subsequent results from our collaboration, and seeing a couple of days' dailies that looked kind of sketchy — very sketchy — perhaps film noir, and then seeing other scenes that were fatter and richer in contrast, I began to say, "Hey, this movie is much prettier in color than it is in black-and-white."

I believe that the photographic style of this movie happened by itself through an interesting compromise between what Dougie loves to do and what I wanted from him. We each came halfway and we found what will now be, hopefully, the continuing style of the Raiders saga.

There are all sorts of things that we had to consider, like the Raven Bar. I wanted the Raven to have big shadows on the wall. So Dougie gave me these wonderful shadows on the wall, but I wanted black shadows and a good way to get black shadows is not to use any fill light. However if you don't use any fill light, you can't see the eyes, and with the film as fast as it is today, one arc light, when directed against somebody, and continuing on and hitting anything other than black dubatine, is going to reflect back and fill in your shadows. The walls of the Raven Bar and Raiders of the Lost Ark were kind of cream adobe sod color and they took a lot of the key light and just sent it right back and diffused the shadows against the wall, so I didn't exactly get my Brechtian black against white on the walls, but Dougie still achieved a very classy, moody look.

In the Peruvian sequence, which was actually shot on Kauai, in the Hawaiian Islands, I wanted a real jungle feeling — a walking into a kind of netherworld that we hadn't seen before. And I just love the way the sun in the morning would come through the flora, so we used so much smoke outdoors in broad daylight just to get the sunbeams, those shards, to show that it became a running gag all through the film. We would be constantly saying, "Are any shards showing yet? No? Then more smoke." And Kit West, the effects man, would go running through with his hot smoker, chasing the wind. Of course, the wind would shift and Kit, who preferred to work alone, and weighed over 200 pounds, would suddenly double-time right across a meadow and he'd pump the smoke in. Sure enough, the smoke would get there and the wind would shift again and you'd see the little figure of Kit running 60 or 70 yards across the meadow, running like Earl Campbell. This happened constantly, but with a lot of patience in Hawaii and still staying ahead of schedule we were able to get some really nice atmospheres with smoke.

“It was just a fascinating experience, working with one of the great British cinematographers for the second time. He’s such an artist, such a responsible artist, and yet he is such an eccentric at the same time.”

Dougie, more than any cameraman I've ever worked with, uses the sun as a key arc light, and lets essentially everything follow its route. I remember, in India on Close Encounters, where Dougie kept saying, "Can we choose the location according to the azimuth of the sun?" I remember picking the location that we eventually selected for Close Encounters based on where the sun was going to be, and when Doug and I went on a recce, in Tunisia, we placed the stakes for the exterior sets according to Dougie's predictions of where the sun was going to be five months hence, which I had never really done before. In working with Vilmos Zsigmond [ASC] on Sugarland Express, I found that he hated the sun. We always waited for the clouds to cover it. On Jaws, the sun was the most taken-for-granted issue. It was always out and we didn't care whether it was front, side or back, as long as the shark worked. So, really, for the first time, I became aware of how the sun could be used as a tool of great artistry and I think Slocombe used the sun on Raiders the way Vittorio Storaro [ASC, AIC] uses his amber smokey units inside to such great effect.

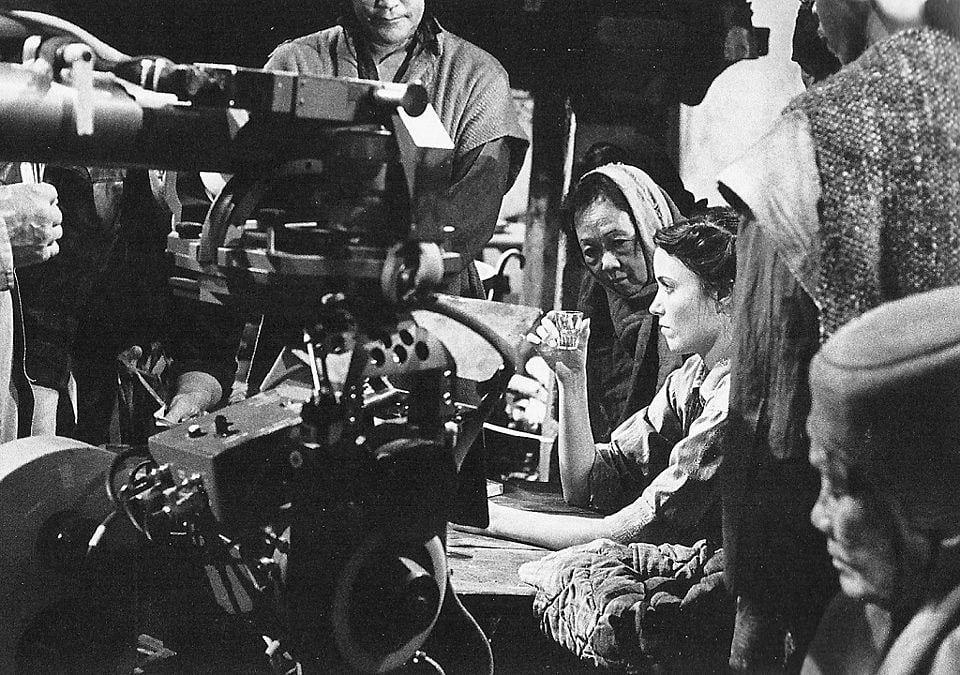

Dougie Slocombe is an amazing connoisseur when it comes to photographing women. I took Karen Allen's freckles off with makeup and then Dougie took over from there and made her look just wonderful. She was marveling in dailies how she had never appeared better in movies and, as far as she was concerned, real old-fashioned Hollywood photography. We were marveling at how wonderful Karen looked, and didn't we wish that style would come back — not for all movies, but for films like Raiders.

“Dougie is also one of the few cinematographers I’ve worked with who lights with hard and soft bounce at the same time.”

Dougie would take at least twice the time lighting Karen as he would Harrison. Now, this is nothing against Harrison, because my image of Harrison was always Fred C. Dobbs out of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and — 5 o'clock shadow and the kind of grumpy and grizzled view of everything. Where Harrison was concerned, Dougie would say, "We're ready." And I would be amazed at how quickly I'd be back on the set shooting with Harrison, but where Karen was concerned, I would be on the set pacing for a long time, saying, "Dougie, how are we coming?" Dougie would smack his lips together — smack his tongue, which was characteristic of Dougie — and he would say, "Oh, 10 minutes." I'd always hear 10 minutes for Karen — 10 minutes meaning half an hour — and with Harrison it would be five minutes meaning 15, which I think was part of Dougie's charm.

Dougie always managed to be a little bit off on his estimates of lighting by saying 10 minutes. Even on shots that I knew would take an hour, he would always say 10 minutes, because it would placate me for 10 minutes and he knew I would be sitting off in a corner somewhere leaving him alone to light and do his thing. I'd be off talking to the actors and preparing something else, and I'd come back in 10 minutes and say, "Are we ready yet?" He'd say, "Ten minutes." Then I'd go away for 10 more minutes and it was a ritual we shared all through the shooting that still brought us in 12 days ahead of schedule.

He is wonderful with photographing women. Then I recalled how well he made Vanessa Redgrave and Jane Fonda look in Julia, and how marvelous he made everybody look in The Great Gatsby. Of the remaining great British cinematographers Dougie is the greatest and at the rate he is going, he will be the greatest for many decades to come.

It's interesting that there are so many different schools of thought and philosophy about lighting. Dougie uses a lot of small units to light brightly and yet sketchily. He uses a fill light unit called the "Basher" — which I would walk around turning off and he would walk around turning on — and at times it became another running gag. At the last moment, Dougie, feeling a little bit insecure with the amount of fill light, would get the Basher and actually hold it and walk around the camera during a camera move with the Basher on everybody. He will put so much diffusion in front of the Basher that you could hardly see the difference in dailies, although it is there and that is the difference between a great artist and just another director of photography. He uses it to really wonderful effect, and yet it became a running gag with us because I love heavy backlighting with very little fill, especially when I am looking for a kind of heavy, down mood. Dougie likes his down moods a little on the lighter side.

It was just a fascinating experience working with one of the great British cinematographers for the second time. He's such an artist, such a responsible artist and yet he is such an eccentric at the same time. In a way that you would never imagine.

For the sequence with the snakes, in the Well of Souls, the big dilemma there was the torches. At first there is motivation for light because they take the great stone off the top, and they look down 50 feet to the floor covered with a carpet of snakes.

I wanted a lightning storm to occur then so it would be easy to motivate some lighting mysteriously edging the snakes as they crawled and slithered and consumed each other and laid eggs and were generally acting horribly. But then what happens when Belloq, the French archaeologist, seals their doom by sealing the tomb and they are trapped in this huge snake pit with torches going out one at a time until only one remains? Where does the light come from? It was a problem that Dougie and I dealt with over a period of a couple of weeks, trying to rationalize how we could still see the 30-foot jackal statues and the hieroglyphics on the walls when we were down to one torch. We decided together that we would just take license and provide an "invisible movie light" that Hollywood invented 40 or 50 years ago and that comes in handy for such situations. It is what I like to call "nothing ambiance."

It was a kind of nothing ambiance that I think every director is faced with at one time or another when you have no light source motivation. You don't have windows, you don't have cracks in the doors, you don't even have a keyhole. You're trapped in a black room, so where does light come from? It is a really interesting dilemma. Dougie chose to do it with very, very soft bounce light for overall ambiance, which gave it a no-light look. I'm specifically referring to the scene where the jackal statue falls over, or there is no light because Marion's torch goes out, and before the jackal statue breaks through the wall and allows the second source of soft light to filter through the catacombs, a very soft blue light.

“The cinematographers whom I admire most are the ones whose style I can’t recognize from film to film.”

Dougie is also one of the few cinematographers I've worked with who lights with hard and soft bounce at the same time. He really varies his light. Sometimes he'll soft bounce or hit with a Basher through about a half-inch of diffusion someone in the foreground who is in a softer part of the set, and yet someone near a harder window in the background will come in with the full force of a direct arc. Just the contrast between those styles within the framework of also using warm light and cool light and mixing the two can be exquisite.

I know Storaro works this way, and I know that Derek Vanlint worked that way with Ridley Scott on certain portions of Alien, but I haven't seen that style used very often — mixing a whole variety of tones and atmospheres in one shot. Life is like that, but so often cinematographers find something that works successfully for them (as do directors) and use it again and again. I know that I have to concentrate on changing my style from film to film or often I'll be tempted to repeat techniques or approaches that have proved successful before.

The same thing holds true for cinematography. The cinematographers whom I admire most are the ones whose style I can't recognize from film to film. There are cinematographers who I could tell you in the first reel who it is without seeing the credits. There are others who remain full of surprises by always changing outward persona through allowing the story to suggest the visual style, not the other way around.

This is not dissimilar to the work of a great actor — Laurence Olivier, let's say — or an American actor like Robert De Niro, who really puts on disguises and doesn't want to be Jake La Motta when he is making True Confessions — and certainly those two styles are as different as anything in the De Niro repertoire. Among cinematographers there are some like Owen Roizman [ASC], whose visual approach to The French Connection appeared to be 180 degrees opposite of what he did in Return of a Man Called Horse, which I feel is one of the best photographed outdoor productions I've seen in a long while.

On 1941 I used the Louma Crane very extensively throughout the production, but on Raiders I used it only twice — once in the Well of the Souls set in order to reach up over those 35-foot statues and look straight down at Indiana Jones climbing toward us. But I probably used the Louma Crane better than I've ever utilized it for one particular shot in Raiders that is, sadly, not in the picture. Only a portion of it remains. I had designed a drinking contest that takes a substantial amount of screentime. It went on for almost five minutes — which is the reason it now runs only two minutes in the movie. It didn't conform to the pacing of the rest of the picture and was really out of place. But it was the best use of the Louma Crane that I've ever experienced.

In that shot the Louma Crane begins at the top of the stairs in this Nepalese bar, Marion's tavern, and comes down past all the French climbers, Australian climbers and Sherpa guides, down through all the women and Mongolians, right to a closeup of the man who's drinking next to someone we have yet to see. He finishes his drink and the Louma pans with the empty glass, which joins 20 other empty shot glasses and you suddenly realize that this has been going on a long time. Then a rather delicate hand takes a full glass filled with liquor and reveals, for the first time, Marion Ravenswood, drunk and feisty. The Louma loosens to a two-shot as they have one more drink and the Louma continues to loosen as Madlo, who runs the bar with Marion, takes all the empty glasses to the bar. So the Louma then cranes 45 feet to the bar past at least 70 extras, all of whom have a stake in this contest — loud shouts, money flashing in the foreground, etc. He refills the drinks and the Louma slides into a super-close tight shot of eight glasses being refilled. Then the Louma eases back and returns to the table, but not to the close group shot at the table. Instead it angles to a high cluster shot of 100 people pressing in around the table for the final drinks. Then we make a complete push in — very slowly — as the final drinks are consumed, panning back and forth (like at a tennis match) and finally stopping on Marion for her last drink. She survives, the camera following her last empty glass to the challenger's full one. He drinks and falls off his chair, breaking it. The Louma goes back to Marion. The whole room erupts with cheers and applause. Marion stands. The Louma eases back and moves to the opposite side of the set, 90 degrees from where it began, and finishes the sequence.

The Louma people believe this was the most extensive use of that special camera crane, with the exception of the opening title shot of Roman Polanski's The Tenant, where it crawls up the side of a building, goes through several windows, out a few doors, beyond a fire escape, and on and on and on … I gave Jean-Marie Lavalou, who is one of the Louma Crane's inventors, a print of that shot as an almost guilty apology for not using it in its entirety in Raiders.

Not only did I not have more need for the Louma Crane in filming Raiders, but I actually didn't have it in the budget. We were really cutting corners. One might complain: "You had $20 million and you couldn't afford the Louma?" We couldn't even afford the Panaglide for the whole picture because we were really pressed. We had almost $4 million in sets alone, and when you multiply that against $100,000 per shooting day on a distant location, and everybody's salaries, and what it costs today to shoot a movie internationally (whether it's a big picture or a small one), you start to see why the film cost $20 million.

In order not to allow it to get away from us, devices such as the Louma and Panaglide had to be sacrificed. The same held true for extras. I wanted 2,000 Arab diggers. The costs would have been very high. The challenge became: making 600 diggers look like 2,000.

In the original script, Kasdan embroidered dozens of images to take us from one country to the next — huge montages from San Francisco to Nepal, from Nepal to Cairo, from Cairo to the Mysterious Island in the Mediterranean. To save money, I finally decided to show a map of the world with little animated travel lines tracing the route of our adventures.

Another example of cost cutting (and upward compromise) was a sequence in the script that called for Indiana Jones to fight a Arab swordsman. It was written as the definitive whip vs. sword duel. It was two pages of prose scheduled for a day and a half of shooting, but Harrison Ford had a bad case of the local turistas that day. Instead of shooting what was in the script, I simply had Harrison pull out his service revolver and shoot the Arab. We were then another day ahead of schedule and that moment seems to be one of the real surprises in Raiders.

Our first week of shooting was on the water, which recalled many horrible memories. It was in La Rochelle, France, and it was the sequence in which the Bantu Wind, the pirate ship on board which Indiana Jones has secreted himself and his lady and the Ark of the Covenant, is overwhelmed by a Nazi sub and a lot of storm troopers who re-recover the Ark. That was shot in the open sea aboard a real tramp steamer of Egyptian registry. The submarine pen was a real World War II sub pen with faded Hitlerian inscriptions carved onto the walls. It was really like time-tripping backwards. The sub pen was pocked with tens of thousands of shrapnel chips and the ceilings had 12-foot craters from those 10,000-pound bombs that were dropped by the R.A.F. They never could penetrate the steel and concrete.

Those pens were also famous because the first allied skip bombs (torpedoes) were used on the doors of the pens, which were in service all through World War II. There was an actual working scaffold and a train overhead that was used to off-load and on-load. Dougie put a bunch of 9-lights up there and we actually photographed it to look like a sort of twisted mothership hovering over the U-boat to grapple and secure the Ark so that it could be hoisted out of there. That was quite an interesting location. I enjoyed it.

Probably the strangest experience I had in Tunisia was when, on the second to the last day of shooting, I had 200 extras lined up for a shot that really required them to be in specific places and hit their marks. We cut their marks (little crosses) out of wood. When we didn't get the shot before lunch, Robert Watts said, "Lunch — one hour." And all the Tunisians took their marks to lunch with them. When we came back 40 minutes later, we had 200 extras running around saying, "Where do I stand? What do I do with these little things?" Most of them thought they were souvenirs.

There are several matte paintings in Raiders, but the audience doesn't seem to notice them — which is good, because matte paintings fail when noticed. In this film they were only meant to be part of the experienced production value. The establishing shot of Nepal and the Raven Bar is a wonderful matte painting. My least favorite painting in the picture — a painting that resulted from the rush to complete the movie — is a matte involving the Pan American China Clipper, parked at the harbor. That was a wonderful painting, but I thought that the background was a giveaway. I just didn't feel that the background was compatible with the water that we shot. The plane was actually at drydock and the water and the harbor in the background (behind the plane) were added. More successfully, the painting of the staff car going off the cliff right in the middle of the chase is a wonderful combination of a matte painting and stop-motion photography of the little figures tumbling out of the plummeting staff car, their hands clawing the air as they fall to their doom — and on the Chapter 12 of our "feature serial."

The last four minutes of the picture is a combination of opticals. It certainly goes wild from that point on and that's where most of our effects money went.

Everything at the top of the Well of the Souls at night, when the storm is approaching, involved a combination of effects. They are digging and digging to get into the Well for the first time, with the torches and the German encampment in lights to screen left below. And there are those rather celestial clouds moving in, with forks of lightning hitting the horizon, zapping overhead. That involved some amazing matte painting work combined with the cloud tank photography invented for Close Encounters.

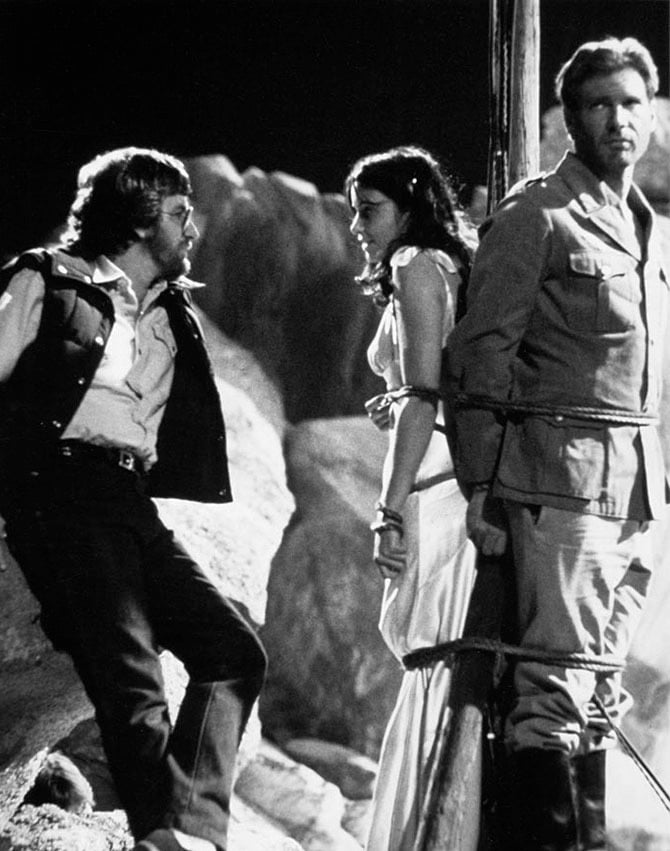

The 12-foot rock which chases Harrison Ford in the cave sequence would have killed whoever it ran over — if it ever had. We went to great lengths to make a 12-foot rock out of fiberglass and wood and plaster precisely so that it wouldn't weigh as much as a real 12-foot boulder. So whether it weighed 300 pounds, which it did, or whether it weighed 80 tons, as it would have, it could still have done bodily harm to anyone falling beneath it — and Harrison was not doubled in those scenes. Not only that, but the sequence was shot in the second week of principal photography in London. I mean, the absolute worst time to eliminate your leading man is in the second week, but because the rock was more effective chasing Harrison with Harrison running toward camera, it just didn't work as well having him doubled. A double would have cheated his head down, so Harrison volunteered to do it himself. He succeeded. There were five shots of the rock from five different angles — each one done separately, each one done twice — so Harrison had to race the rock ten times. He won ten times — and beat the odds. He was lucky — and I was an idiot for letting him try it.

There were no miniatures involved in that sequence. The Peruvian caves were full-size sets, with a full-size boulder. The rock was operated by a cam and rod, a steel rod that came out from the side of the set, disguised by rubber stalagmites and stalagtites, and very underlit. When the rubber was disturbed you couldn't see the stalagmites and stalagtites moving as the ram on rails guided the spinning rock from the beginning of its run to the end of its run — about 40 yards.

“I’m definitely going to direct the sequel to Raiders. I had such a good time making the first one that I would hate to let the second one slip through my fingers into somebody else’s hands.”

As for the Peruvian natives — they were Hawaiians who looked like Peruvians. We interviewed a lot of Hawaiians. A lot of them looked too Hawaiian, but all those who looked more South American we hired. They were heavily disguised in war paint.

Glenn Randall was the stunt gaffer on the film. He assembled an international cast of stunt experts from Italy, Spain and America, including Terry Leonard from the U.S. and Vic Armstrong who did a lot of the location doubling for Harrison. We also had Wendy Leach, Martin Grace, Jack Dearlove, Chuck Waters, Bill Weston, Paul Weston, Billy Horrigan, Rocky Taylor and Sergio Mione, a wonderful man who portrayed the last Nazi in the truck chase, the mean sergeant.

There were so many dangers to everyone involved, because the picture is all stunt work and spills and close calls and cliff-hangers, that we would just wear these guys out like "Wash 'n Dries." That, combined with the "Tunisian Revenge" from the hotel food, meant that they would lose their punch and have to go away for 12 hours to regenerate, while somebody else would step in.

Nobody was seriously hurt, but at one point we had a near-disaster when the flying wing actually started to run over Harrison Ford's right leg. He tripped and the wheel began to move across his tibia — before they could shut off the hydraulics. About 40 crew people were trying to rock the airplane off his leg and the only thing that saved his leg from shattering in a hundred pieces was the fact that it was so hot that the rubber was soft and pliable and the ground concrete pad was covered over with two inches of sand. Because of this there was enough give between the rubber and the sand that Harrison completely escaped any harm. That was our closest call on the picture — that and the real biplane that Harrison crashed in on the last day of shooting in Kauai, Hawaii.

Terry Leonard took some pretty nasty spills during the truck chase. He went out of the truck at least three or four times, as did Charles Waters. Waters took some very bad spills, landing on this head twice, but what broke his fall was the fact that every time somebody falls out of a truck the action is staged so that he falls down an incline. In those old serials where you see the Good Guy jumping off his horse onto the Bad Guy's horse to drag the Bad Guy to the ground, they are almost always rolling down hills. You rarely see them hitting flat ground. This was the same in Raiders. The philosophy of the stunts was no different from the philosophy which Yakima Canutt used in pioneering so many of the stunts that we take for granted in movies today.

I must say that a lot of the credit has to go to Glenn Randall, who not only did a lot of the stunts himself (always making sure that safety came first), but Glenn personally invented a lot of the stunts that are so exciting in the movie — like the stunt where Terry goes under the truck hand-over-hand. That was Glenn Randall's invention. According to my storyboards, Indiana was merely to slip and find himself in danger of having the whole truck run over him. Then, as in the Yakima Canutt stunt in Stagecoach, in the last instant he was to grab hold of the tailpipe with his whip and climb back on. But Glenn's better idea — to let him crawl hand-over-hand underneath as the truck roared ahead at 45 miles an hour — is probably one of the show's best stoppers.

I loved the experience of filming Raiders. I don't know if it was the good fortune I enjoyed on this particular adventure, but I'm anxious to work again overseas.

I'm definitely going to direct the sequel to Raiders. I had such a good time making the first one that I would hate to let the second one slip through my fingers into somebody else's hands. I'll certainly not be involved in the third or fourth one, but I really want to do the follow-up, because the new story is even more spectacular than Raiders of the Lost Ark.

I've had to push back a few more years the promise to myself to make a number of small, Truffaut-esque pictures, although the one I'm currently doing, A Boy's Life, is the smallest movie I've ever made — under $10 million, and all with children. It's the kids' picture I've been anxious to do for several years.

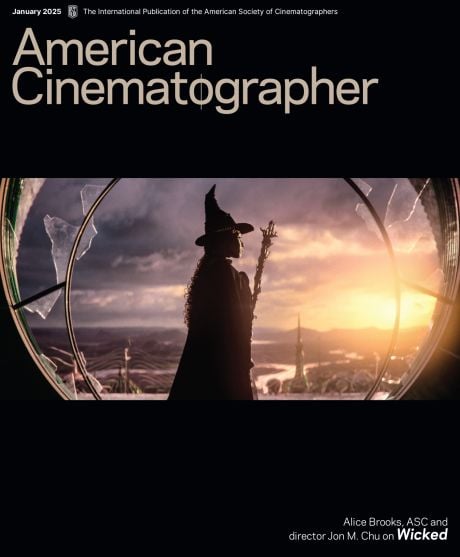

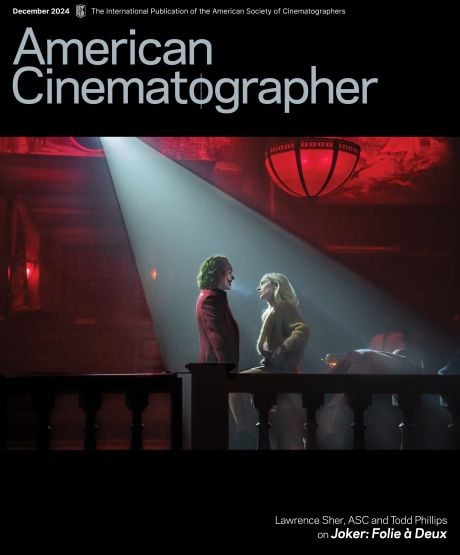

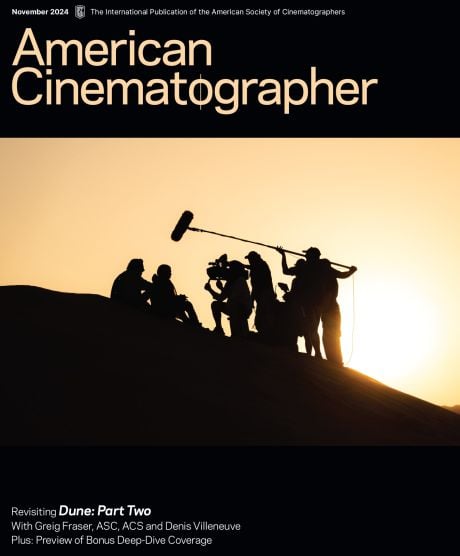

This article appears as it was originally published in AC in November of 1981. Some images are additional or alternate. Spielberg and Slocombe would both earn Oscar nominations for their work in the picture, which became a smash hit.

You'll find our feature on shooting the 1984 Raiders sequel Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom here, the 1989 followup Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade here, and 2008’s Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull here.

A Boy’s Life was the “cover” title used during the shooting of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, photographed for Spielberg by longtime friend Allen Daviau, ASC.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.