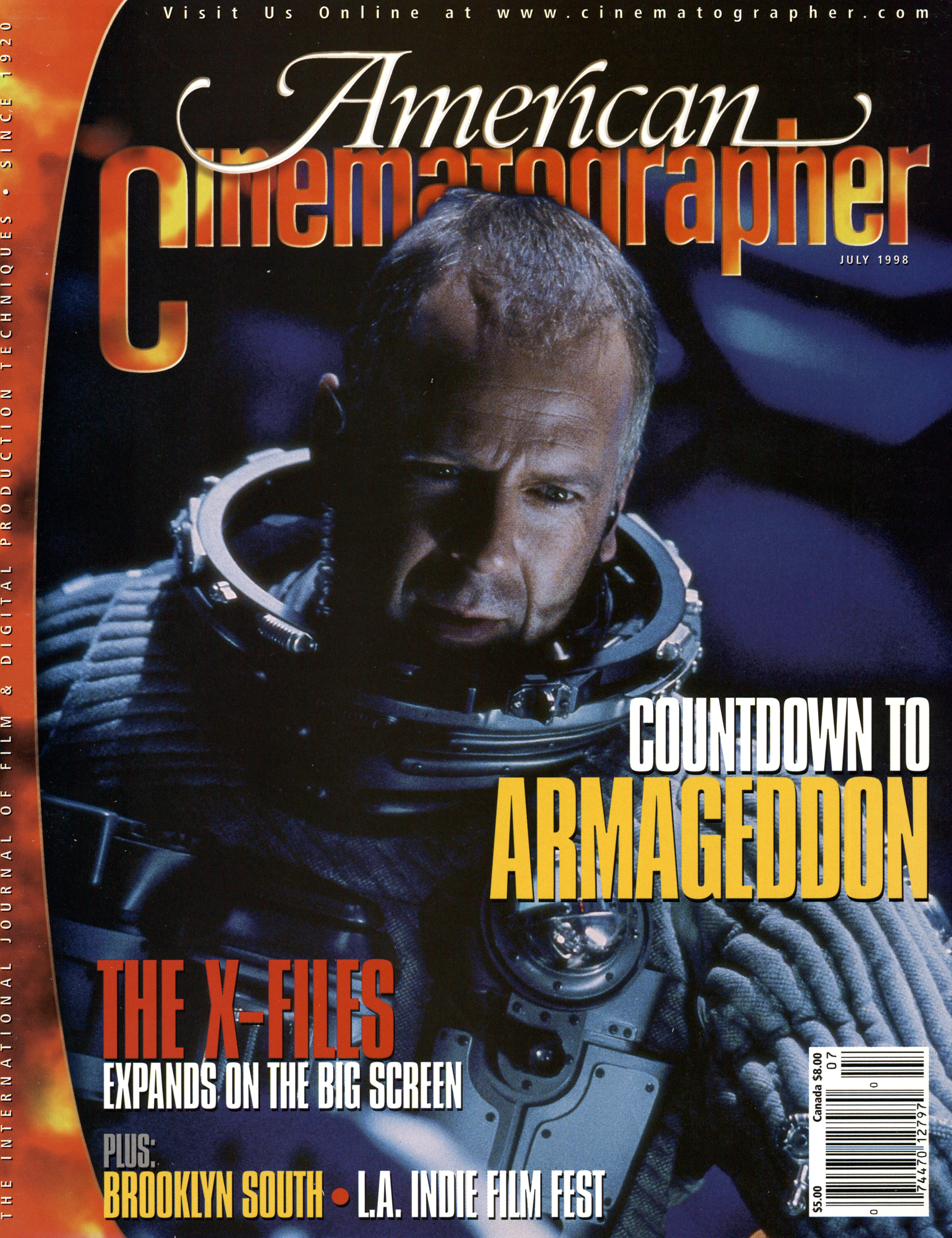

When Worlds Collide: Armageddon

Cinematographer John Schwartzman, ASC reteams with director Michael Bay to expose Earth to a planet-threatening asteroid.

This article originally appeared in AC, July 1998.

Unit photography by Frank Masi, courtesy of Touchstone Pictures and Jerry Bruckheimer Productions.

Despite being a dauntingly complex project budgeted at more than $100 million, the concept for the sci-fi adventure film Armageddon seemingly dropped out of the sky. Director Michael Bay recalls, “After The Rock, I didn’t want to do just another action movie, but I couldn’t find a story I liked. I was working with [executive producer] Jonathan Hensleigh, trying to come up with an idea, and he said, ‘You know those horseshit asteroid-destroys-the-world movies? Well, what if we did a really cool one?”’

Their tale opens as astronomers discover a Texas-sized object hurtling toward Earth: a “global-killer” asteroid like the one which wiped out the dinosaurs. In an early indication of the threat, shards of the stupendous slab rain down to perforate New York City. Mankind’s survival strategy is to launch a pair of next-generation space shuttles, land on the planetoid’s surface, sink a shaft into its core, and insert a nuclear weapon. The blast is designed to split the asteroid in half, causing the pieces to pass by Earth.

Tapped to join the landing team is a crack oil driller (Bruce Willis), who insists on bringing along his band of roughnecks (including characters played by Ben Affleck, Steve Buscemi and Will Patton). The first half of the picture illustrates NASA’s attempts to train this motley crew for the mission, while the second witnesses their brave attempt to rise to the momentous occasion.

“The scary thing is that these global killers pass us all the time,” Bay says, recalling the worldwide scare this past March over Asteroid XF-11, a two-mile-wide object which was mistakenly projected to hurtle within 30,000 miles of our home world in the year 2028. “That’s one of the reasons why I was interested in this story. It’s totally heroic — these everyday Joes have to save the world, and it depicts the best of the space program. In fact, I kept thinking about The Right Stuff throughout the process of making Armageddon, because I wanted to capture that same heroic spirit I felt as a kid while watching the space race to the moon.”

Countdown

Preparations for Armageddon geared up in early 1997 as Bay began working with storyboard artist Robbie Consing (The Game) and production designer Michael White (Crimson Tide, The Jackal), both of whom had worked on The Rock. The director says, “Literally everything had to be designed: state-of-the-art space shuttles, space suits, a Mir-style space station, the asteroid itself.”

However, such scope doesn’t come cheaply, and as Bay recalls, “The production hinged on NASA giving us full cooperation. We knew we couldn’t make the movie without them.”

Producer Jerry Bruckheimer, whose credits also include such strikingly visual films as Con Air (photographed by David Tattersall, BSC), Crimson Tide (Dariusz Wolski, ASC), and Flashdance (Don Peterman, ASC), was instrumental in earning the trust of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. “We submitted a script very early on,” Bruckheimer explains. “If NASA says ‘Yes,’ then you have to go to the Air Force and the Department of Defense — they really control the situation. I had a good relationship with the DOD on Top Gun, so that helped. And even though they didn’t sanction us on Crimson Tide, I don’t think they were disappointed with the movie because it made the Navy look professional and honest. That’s [the image] they’re looking for.” After some minor script changes for accuracy’s sake, the doors to NASA’s immense facilities at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida and the Johnson Space Center in Texas were opened wide for the filmmakers.

Returning for Armageddon was the core production crew that had tackled The Rock (AC June 1996), headed up by director of photography John Schwartzman, ASC, a longtime friend of Bay’s and a frequent collaborator on music videos and commercials. “One of the nice things about this film was that getting all of us back together was like getting a bunch of old friends together,” the cinematographer offers while taking a break from his duties on director Ron Howard’s upcoming comedy Ed TV. “There was no feeling of ‘I’ve got to learn how to work with these other people.’ It was more like, ‘Let’s get back to work.’”

Analyzing his working relationship with Schwartzman, Bay wryly offers, “John knows what I like, and he can handle it when I say, ‘This lighting sucks, let’s do something else.’” The director specifically refers to a dramatic night scene in Armageddon featuring actor Billy Bob Thornton: “I was bored with the lighting we were using, he was tired, and I said, ‘Let’s do something different.’ So John shot back, ‘Well, what do you want to do?’ I then said, ‘Well, I don’t know, John...’ and the crew started walking away from us as if we were in a fight. That’s just the way we work. I trust his exposures and I think he trusts my eye for camera placement and how things will cut.”

The situation in question “was a classic,” Schwartzman says with a laugh. “Almost every two weeks we’d have a pushing and shoving match, and the good thing about it was that it was never personal and something great usually came of it. That type of thing clears the air, and Michael is a director who never carries a grudge. If you do something he doesn’t like, he’ll let you know and then just move on. We can sometimes frustrate each other to no end, but we’re both trying to make the best movie possible.”

Director Michael Bay estimates that NASA and the U.S. Air Force allowed the production to utilize approximately $19 billion worth of aircraft and facilities during the Armageddon shoot.

![Director of photography John Schwartzman at the base of a "locked and loaded" space shuttle at the Kennedy Space Center. The cameraman notes, "In one respect, NASA is of the highest technical order, but like everybody else, they're working within very strict budget restraints." Administration officials were very impressed by some of the cameraman's lighting gear: "They loved the fact that we brought all of this new technology to them. Our technology is much more current that NASA's. Anybody there would admit it. For example, the shuttle itself is a 1970s design. My PowerBook laptop is more powerful than any single computer in the firing room [where shuttle launches are coordinated]. It's just that all of their systems run perfectly, and look really cool."](/imager/uploads/563361/Armageddon-Schwartzman_6c0c164bd2b597ee32b68b8b5755bd2e.jpg)

Following his breakthrough success with The Rock, Schwartzman shot Conspiracy Theory, a big-budget action-thriller directed by Richard Donner. Gaining NASA’s cooperation was immensely helpful in shaping Armageddon's content, but the cameraman’s successful introduction to the anamorphic format on Conspiracy Theory also greatly affected the making of Armageddon at every level.

Though Schwartzman and Bay expressed enthusiasm for the Super 35 process while shooting The Rock, the theatrical prints were a bit of a letdown for both filmmakers. “The drag about Super 35 is the grain and its ‘optical’ feeling,” Bay attests. “We did about 30 ENR-treated prints on The Rock to keep some of the contrast. Those were shown in major cities, but the other prints lost a lot of snap. The film looked good for Super 35, but we were still working with this tiny negative.”

Asked to recount the lessons he learned on Conspiracy Theory, Schwartzman relates, “What became very apparent to me was that Super 35 is not just an optical process that makes the grain more apparent; the grain is also bigger because it’s enlarged so much during projection. You’re getting boned on both ends. The beauty of anamorphic is that there is no intermediate optical process. If you like your dailies, you’re going to love your release print. The larger negative also gives you greater shadow detail and greater latitude, so even though I was shooting deeper stops in ’Scope, I felt I was using [relatively] less light to get more image.

Anamorphic Excursion

“On Conspiracy Theory, I was doing very large night exteriors in New York City, and I needed to be working at least a T4 or 4.5 for them to look good. But that didn’t mean I had to light everything to that exposure. If I could get the lenses to that range, I found that the level of shadow detail I could get in the darker areas was quite extraordinary. One of the things I explained to Michael on Armageddon was that for shuttle interior scenes, I was going to be shooting at a T4.5. I might only have a T2.8 on the actors’ faces, but he’d be able to read them beautifully even though they would underexposed by a stop-and-a-half. The faces wouldn’t be muddy, just dark. I was able to do that simply because of the resolving power you get with anamorphic's big negative.”

However, Schwartzman also found that it was essential to use the proper stop in anamorphic, since the poor performance of the lenses in wide-open conditions can not simply be compensated with fine-grain stocks. He explains, “Let’s put it this way: I would rather be shooting at a T4.5 on [Kodak Vision 500T] 5279 than at a T2.5 on [200 ASA EXR] 5293. The difference in the quality of the lens within this one-stop range far outweighs the difference between 93 and 79, in terms of saturation, grain structure and black densities. Whatever you gain from the 93 will be lost, because at low stops, the lenses have a lot of chromatic aberration and won’t perform. As soon as you get a T4, though, they magically transform into gems made of glass.”

Other specific production needs also made Schwartzman lean toward the use of anamorphic. “In Super 35, any smoke or other atmospheric diffusion is going to make the image fall apart in your release print,” he says, “If you stood back and looked at our asteroid set [built and housed at Disney Studios], you’d say, ‘Those are Plaster of Paris rocks.’ I knew that shooting on the asteroid set would involve putting a lot of debris in the air to cut down the clarity between the subject, the camera, and the set. If I’d shot in Super 35, by the time we got to a release print we would have lost the image’s high end and low end, and been stuck with just the mid-ranges.

“The set was physically debilitating. There were no level surfaces and no spots to be comfortable, so we just couldn’t shoot in there over a straight run.”

“Discussing this issue with Michael, I suggested that we should have as much control over the image as possible. If we wanted to flatten it out, we should. But we should have the choice, as opposed to the lab creating that effect with some intermediate optical step. As soon as he saw the detail and richness that anamorphic offered, Michael fell in love with the format.”

A devout convert, Bay enthuses, “You just have so much more resolution in anamorphic, and the dupes look great. That’s why I wanted to use it even though I had to give something up in the lenses. I like the depth and close-focus effects you can get with spherical lenses, but the sacrifice was well worth it.”

Schwartzman points out, however, that Bay’s definition of “close-focus” is an extreme one: “What he means is that he can’t take a 75mm anamorphic lens and focus it down to 11 inches. He considers the 17.5mm close-focus Primo to be a ‘normal’ lens. On The Rock, when Ed Harris was giving his speeches, the camera was literally 11 inches from his face. Most cinematographers would consider the 180mm anamorphic lens at seven feet to be close — we were routinely working where there were no more measurement markings, at about 4½ to 5 feet. And that is where camera assistants do not want to live.”

Optics engineer Dan Sasaki, who works at Panavision’s corporate headquarters located in Woodland Hills, California, modified Schwartzman’s E- and C-series anamorphic lenses to focus much closer than they normally would. The cameraman contends, “Many American Cinematographer readers probably don’t realize that you can’t just put any lens on any camera and expect it to work flawlessly at all focus distances and f-stops. Each one has its own sweet spot, and you not only have to know where that spot is, but that you can move it around; it’s not set in stone. Richard Mosier, my 1st AC, spent three weeks with Dan working on the astigmatizers and the front anamorphasizers on these lenses, optimizing each and every lens for our use. For example, we thought we’d be generally using our 135mm E-series lens at about 8 feet, so why not maximize the performance of the lens at that distance with a stop of T4.5? Dan is a genius with lenses, and he kept us up and running throughout the shoot.”

Schwartzman reports that his camera of choice was the Panavision Platinum, since its viewfinder offers his operators the brightest image possible. The show carried two Platinums, as well as a Platinum Panastar and a Panaflex Lightweight for Steadicam work.

Interestingly, anamorphic’s inherent lens-flare effect — which some argue is a prime reason not to use the format — actually became an encouraged style element on Armageddon. “Some people hate flares and some people love them,” Schwartzman says. “I tend to fall into the Jan de Bont [ASC] school: I find them interesting and beautiful depending on the source of light giving you the flare. A fluorescent light burn obviously isn’t as interesting as a very small, hot specular kick, but I like to use flares to transition in or out of a scene, or to heighten the sense of energy in a shot. It’s something to be used as a tool, and either added or taken away depending on your needs.”

Bay agrees, adding, “Flares are so cool that we even imitated them in some of our visual effects sequences, like when the shuttles fly past the camera on their way to the asteroid. There are lights flaring out all over the place in those shots.”

To retain full control over their negative, the filmmakers plan to utilize Technicolor’s new dye-transfer process on a number of Armageddon's theatrical prints, making it the first anamorphic-shot feature to benefit from this technology. (It was recently used on the Super 35-shot Godzilla.) They may also employ Kodak’s new Estar-based “Clipper” print stock, which creates a ENR-like effect without requiring any special processing. The cameraman has run some tests with Clipper on his Ed TV dailies, and believes it could add an extra degree of contrast to Armageddon's images. “They’re holding about 20 million feet of this stock for our normal release prints,” he says.

Spacebound

Prior to the beginning of the show’s principal photography, Schwartzman set out to shoot a daytime shuttle launch at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Accompanied by his crew, he brought along 13 cameras to cover the April 1997 event. That alone was a complex task, but NASA’s protocol added an extra degree of difficulty. “After they fill the shuttle’s tanks [with liquid oxygen and hydrogen], there’s a 24-hour lockdown period when nobody is allowed within almost four miles of the launch pad,” Schwartzman details. “But we had cameras within 150 feet of the pad, so we had to figure out a way to set these cameras up, let them sit for two days in the Florida heat and humidity, and have them operate perfectly.”

Because NASA rules prohibited the filmmakers from using their own camera-activation system (which could have interfered with the space agency’s finely tuned electronics), a special code was added to the computer launch sequence to trigger Schwartzman’s array 45 seconds before main-engine ignition. “Organizing that was easy,” the cinematographer maintains. “The difficult part was explaining to Panavision that we had to leave these cameras — including Panastar IIs rolling at 120 fps — out in the middle of this sweltering swamp for a couple of days. I had to know that these cameras — loaded and ready to roll — would work.”

Toward that end, camera assistant Richard Mosier conducted a series of tests and made special preparations. Two 65mm camera power supplies were linked together to ensure that each camera’s batteries would operate for at least 48 hours. To prevent condensation from forming on the lenses, each was rigged with a ring of 25-watt bulbs that would cause any ambient moisture to evaporate. Finally, blastproof bunkers were built for each camera. “It all worked perfectly,” Schwartzman confirms. “The footage is spectacular.”

However, Bay later had a sudden inspiration that would send Schwartzman back to the Kennedy Space Center six weeks later. As the director tells it, he was in a NASA bathroom when he happened to look up and see a large poster of a shuttle blasting off into space — at night. Taken with the image, Bay changed the film’s script to include a night launch. “We used both of the launches we filmed in the picture,” Schwartzman says. “But from a photographic standpoint, the night launch may have been the most challenging part of the movie.”

As the shuttle sits on the pad at night, it is lit by 40 10K Xenon lamps, bathing the enormous vehicle and towering gantry structure with some 200 footcandles of light. “That gave us a decent stop,” Schwartzman begins, “but as soon as the solid rocket boosters ignited, we’d suddenly be up to 16,000 footcandles in about 11h seconds. We could have used some sort of photocell with an auto-iris controller, but I didn’t want to have a dynamic exposure change affect the footage.” The cameraman’s alternate solution was to preset the exposure on each of his individual 15 cameras, determining his stop by calculating each unit’s distance from the shuttle, the angle of the shot in relation to the launch sequence, and the orbiter’s altitude as pictured in frame .

Determining these set exposures required some inventive research. “I contacted this wonderful guy named Red Huber, a still photographer from the Orlando Sentinel who has shot every single shuttle launch,” Schwartzman explains. “Studying his photographs, I selected some specific shots and determined where he was set up to get each one. Red and I then went though each photo, and he told me which stock, the shutter speed, and f-stop he had used. From there, I figured out what the stop should be for each of my cameras, based upon the use of [Kodak’s 100 ASA EXR] 5248 and my various frame rates — which were anywhere from 24 to 120 fps. NASA had given me a bunch of information about the footcandles produced during the launch, but most of it turned out to be wrong, so I couldn’t have done this scene without Red’s help. Also, shooting the day launch told us which angles worked best with various frame rates and focal lengths.”

While all of the night launch footage turned out beautifully, the cameraman reports that an Eyemo camera fitted with a 40mm lens, placed some four miles away from the launch pad, may have produced the “hero” shot for the sequence.

On the Rock

During a subsequent two-week “mini-shoot,” the filmmakers traveled to Washington D.C., New York City and then Texas to film exterior establishing material and “Americana” footage that would give the picture’s story a broader emotional scope. The production then moved on to the Badlands of South Dakota to begin shooting scenes set on the asteroid.

In the film, the shuttles Independence and Freedom crash land on the stony juggernaut’s jagged, storm-wracked surface. The landscape is violently active, with hot gases erupting though the crusty ground as the surfaces quakes with tremors. Towering crystalline formations stab upward, making the barren world appear even more aggressive and hostile.

Shaken after their hair-raising voyage through space, yet driven to succeed, the members of the Earth’s demolition crew don their space suits and rev up a pair of six-wheeled all-terrain vehicles called “Armadillos.” Protected by their artificial skins, the intrepid heroes begin searching for a prime drilling site. In these scenes, Armageddon’s cinematography and production design mesh seamlessly to render a fantastic new world.

“Like every good movie, we started with some of the toughest stuff,” Schwartzman says of the Badlands shoot. “On the first night, we were lighting up about five square miles of landscape.”

“We had more trucks than I’ve ever seen in my entire life,” Bay confirms, “john had two Major Muscos, an SMS Nite Sun, and about 40 18Ks — it was really unbelievable.”

Given Bay’s penchant for cool-blue night exteriors, Schwartzman’s fixtures were primarily uncorrected HMIs, which allowed him to get the most from his wattage. Roads were cut to create a “Musco Highway,” allowing the cinematographer to position his immense fixtures, while seven miles of cable were run to provide power. Schwartzman recounts, “We also had a Night Sun and 27 6K Pars — a lot of stuff — just to light up this landscape. And it was beautiful.” However, the illumination also attracted the attention of every flying insect within a 100-mile radius, causing huge clouds of the creatures to collect around the lights. Fortunately, the various fixtures served collectively as the world’s biggest bug zapper. “The heat killed them all by the second night,” the cameraman says.

Schwartzman credits gaffer Andy Ryan and rigging gaffer Jeff Soderberg with laying down the electrical infrastructure for the shoot over a period of two weeks before the main unit arrived. “To maximize the location, we were moving the Muscos two or three times a night, but because we were so organized, it happened without a problem.”

The Badlands portion of the shoot was not without its mishaps, however. The first night’s work consisted of a scene in which the members of one shuttle crew pull themselves from the remains oftheir wrecked ship. Bay details, “We’d created this amazing crash site, using airplane parts trucked in from Arizona, and the first setup was a massive wide shot. Unfortunately though, nothing was working that night. Our 100-mile-per-hour fans would start and stop, the steam machines would blow fuses — everything had failed before we even broke for dinner.”

The crew returned to again try to film the establishing wide shot. “We were so far back that the actors looked like little dots,” Bay describes. “Ben Affleck was the first to be seen climbing out of the wreckage, but as he was walking out, he kept leaning down, as if he was trying to find something on the ground. I radioed to him, ‘Ben, what are you doing?’ There was no response, because his line was shorted out. He kept reaching out for something on the ground, and it turned out he was looking for a rock so he could smash his helmet’s face plate — he couldn’t breathe! We had to work out all of these kinks in the suits before Bruce Willis came onto the show; the other actors were sort of like guinea pigs in that process!”

Back to NASA

Granted complete cooperation, Armageddon arrived at the Kennedy Space Center ready to utilize the facility. “As the NASA guys describe it, this is the ‘world of big toys,”’ Bay begins. “And they do have the world’s biggest toys. The vehicle assembly building — where they service the shuttle before and after each launch — actually has its own weather system. They bent the rules for us, and we got the most cooperation since Apollo 13. About the only thing we weren’t able to use was the ‘Vomit Comet’ [zero-gravity training aircraft], because allowing Apollo 13 to use it broke the rules. The FAA says that it would cost $60 million to retrofit the plane to certify it for civilian use. Even with our budget, that was out of the question.”

Shooting at the Kennedy Space Center included adhering to some specific restrictions, since the extent of the Administration’s aid always hinged on safety issues. “There were a lot of restrictions in areas where they were doing things like handling solid rocket fuel, which is of course highly flammable,” Schwartzman says. “We had to have all of our lighting fixtures approved by NASA. Fortunately for me, our rigging gaffer, Jeff Soderberg, did an extraordinary job of dealing with the NASA officials in such a way that they relaxed a lot of their restrictions. For example, they allowed me to bring some 4K Pars in, which they rated as ‘non-explosive’ because the fixtures had sealed globes within globes. And they let me use HMI Pars wherever I needed to.”

However, the immense size of some of NASA’s facilities sometimes left the cinematographer to simply augment the existing lighting, rather than illuminate things as he normally might have done. “In a perfect world, I would have rewired the whole place,” Schwartzman describes. “But while I would have loved to do that, we traveled to the Kennedy Space Center to shoot what was there — to capture the reality and scale of the place. Their lighting served as my base ambience, and from there I worked on creating mood and shadow.” This included adding pools and highlights, and using fluorescent fixtures to create accents.

Interestingly, NASA was quite curious about many of the cameraman’s lighting units. “They asked a lot of questions about my Kino Flos,” Schwartzman remembers. “We’d used a lot of Wall-O-Lites in one building, and this guy later came up and said, ‘Okay, what are these and where do I get some?’ For a moment I thought about telling them that I had designed them, but I gave them [Kino Flo company owner] Frieder Hochheim’s number instead.”

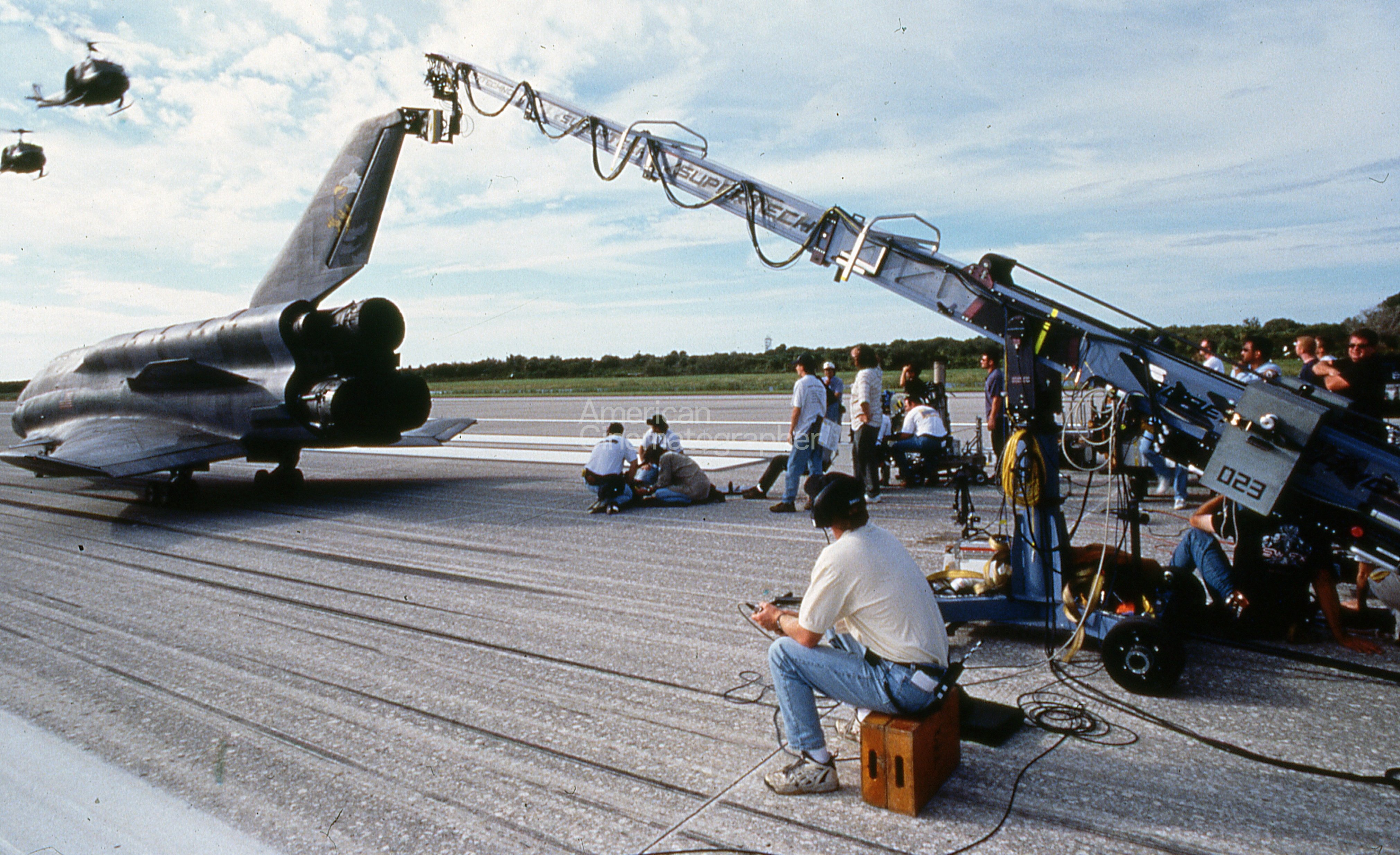

However, lighting was only one of the filmmakers’ challenges, as Bay’s kinetic cameras demanded constant movement. The director recalls, “While shooting in the vehicle assembly building [where the shuttle is positioned with its massive fuel tank and towering solid rocket boosters], we used a Technocrane [obtained from Panavision Remote Systems] for a specific sequence in which Bruce Willis’ character is talking to another guy while walking around the orbiter, with most of the dialogue taking place alongside the wing area. And this was a real shuttle. The guy who runs the facility told me, ‘I’m putting my career on the line. You can’t touch this $6 million Kevlar piece [of the spacecraft wing].’ It was a heat-resistant panel about four feet long — $6 million! So we had Bruce right there and the Technocrane brought the camera within four inches of this wing surface. Later in the schedule, we shot some scenes at a historic Craftsman-style house in Los Angeles, where they told us, ‘You’ve got to watch the floors!’ We told them, ‘Listen, we’re used to shooting around billion-dollar spacecraft, so we’ll be fine.’”

Schwartzman adds that his “accent” lighting within the vast vehicle assembly structure included using 80 6K Pars and wheeling in a Musco.

For the sequence in which Armageddon’s faux space jocks board their ships, the filmmakers were allowed to shoot on NASA’s actual launch gantry, where the shuttle Endeavor stood vertically poised on the pad waiting for a takeoff scheduled for just a few days later. “There are two big issues of concern at NASA,” Schwartzman says, “One is FOD, which stands for Foreign Object Debris, and the other is ‘taping-and-tethering’ — making sure that everything is connected to something else. While we were on the gantry, NASA was far less concerned about me using my lights than they were about someone dropping a screw near the base of the shuttle. Every piece of camera tape had to be accounted for. If we went up there with 42 pieces of equipment, we had to come down with 42 pieces — or we’d stay up there until we found it. Every scrim was wired to its light so it could only fall three feet. We also couldn’t use clothespins to attach gels to lamps because they might spring apart.”

Schwartzman reports that NASA did allow him to run cable up the gantry and bring along a pair of 4K HMI Pars and 1200-watt HMI Pars for fill — working less than 100’ from the bottom of the “locked-and-loaded” Endeavor. “They wouldn’t let us bring in a generator, so we tied in with their 110 AC transformers,” the cameraman says. “In most cases [at the NASA facilities], I had to provide my own power, but the gantry was a special case.”

Adds Bay, “We also shot in the clean-room passageway up there, which leads right to the hatch where the astronauts enter the ship. We hadn’t planned it, but while we were on the gantry, someone from NASA asked, ‘Do you want to get in there...?’ We had just two minutes to get a shot of Bruce Willis and Ben Affleck leaning into the hatchway, but not going inside, so we went with the light we had. Bruce was very funny, whispering, ‘Mike, do you have the cameras rolling? I’m going to make a break for it’ — as if he were going to jump inside the shuttle! But NASA had some technicians in there to make sure he didn’t go too far.”

The “firing room” — a control center featuring a set of massive 25'-tall windows looking out onto launch pad 39B —was one area at NASA where Schwartzman did do extensive lighting. The extra illumination was very necessary, given that he was replicating the awesome blast created by a shuttle liftoff. “The firing room is the closest spot to the pad during a real launch,” the cameraman details. “Of course, I couldn’t get cameras in there when we shot our night launch. But they gave me clearance to work there even though [the Endeavor] was really on the pad and ready to go up a few days later. We could shoot in there from 8:30 to 10:30 p.m. — just two hours.”

Schwartzman began his lighting earlier that day by replacing NASA’s warm-white fluorescents with Kino Flo 3200°K tubes. Outside, 10 Dinos were mounted on 86' Condors and positioned near the main window, along with ten 70,000-watt Lightning Strikes units. “The firing room is located on the fourth floor of the building,” he says, “so the top of this window is about 80 feet in the air. To create a moonlight effect, I also ripped in a couple of 18Ks to add some nice modeling on the interior walls. Then, as the guys went through the countdown and got to T minus four seconds, we throttled up eight Dinos on dimmers to simulate the shuttle’s engines, which are very warm when compared to the solid-rocket boosters. During an actual launch, the shuttle’s engines burn for a few seconds, coming up to 100 percent of their capacity. But they’re not enough to lift the shuttle; when the boosters kick in, the orbiter instantly shoots upwards for 88 seconds until they burn out. The boosters are so bright that at night they light up half the state of Florida. To create that effect, we instantly brought up the rest of our Dinos and set off all of the Lightning Strikes units. What was great was that we didn’t use actors for that scene; the real NASA launch team came in on their own time to do it. They later told me that our launch lighting was very similar to the real thing, but maybe a bit brighter and more dramatic. That was neat.”

Not incidentally, NASA safety protocol banished Schwartzman’s dimmer controls from the fire room, because their electromagnetic operation might affect the sensitive launch computers. Radio communications were also banned for the same reason; this restriction compelled the cameraman to place his dimmer boards in the basement of nearby building and rely on a string of assistants with loud voices to relay his instructions to the board operator. “Basically, NASA didn’t want our lighting-control board in the same room with the big red button that sets off the shuttle’s engines,” he says. “So after I gave a signal, I literally had five people shouting ‘OKAY, NOW!’ down along this chain to finally tell someone to push a button. We had to build that communications lag into our lighting cues.”

Despite such difficulties, Schwartzman contends, “I think our enthusiasm for the space program was met halfway by the enthusiasm the NASA guys had for filmmaking. The public affairs people initially told us ‘You can’t do this or that’ when we arrived, but the facility heads were suddenly put in charge once we started working, and within about an hour there were no restrictions. They were great, and shooting there was a highlight of my career.”

Bay estimates that NASA and the Air Force allowed the production to utilize approximately $19 billion worth of aircraft and facilities during the Armageddon shoot.

The “Pit of Despair”

In addition to the Badlands shoot, portions of the asteroid surface sequences were done with miniatures, while the remainder, primarily the astro-drillers’ attempts to bore into the rocky core, were staged over the course of about seven weeks on Stage 2 at Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California. It was here that AC’s editors visited the Armageddon crew in mid-January of this year. Construction had begun months earlier, after the stage’s 240' x 300' floor had been removed and 30' of soil was excavated to accommodate production designer Michael White’s extreme topography. “That gave us about 90 feet of height,” Bay describes, “which was great because I like low angles. We then blacked out the perms. Because of the set’s bowl-like shape, along with the atmosphere effects we had going, very few sky replacements had to be done in postproduction.”

While Schwartzman initially thought of using a bank of 100 synchronized Vari-Lites to add a sense of movement to the set’s illumination — lending credence to the idea that the asteroid was spinning through space — the plan proved impractical. Also discussed was a single-source approach like the one cinematographer Gale Tattersall recently used while shooting lunar sequences for From the Earth to the Moon. (Ironically, Armageddon had originally planned to built their asteroid set in the same Tustin, California blimp hanger utilized by the HBO project, but ultimately could not book the site.) “I later read about how Gale did that in American Cinematographer,” Schwartzman says, citing the magazine’s April 1998 story. “But his approach worked because he had enough room beyond the set to cast an immense source and get nice sharp shadows. I just didn’t have as much room, because our set at Disney was built to the perms.”

Echoing his approach in the Badlands, Schwartzman’s lighting solution was to once again deploy 12/18Ks and HMI 6K and 4K Pars to create shafts of light cutting through the asteroid’s rocky shapes. He offers, “I could have used another 50 feet of throw for the lamps, but there was just no room. Actually, I wish we could have taken our set and actually put it in a larger space where we could drive a Musco around it. That would have given us our single source.”

Schwartzman notes that his HMIs were primarily Cinepars supplied by Sun Valley, California-based LTM. “I love burning arcs for daylight exteriors, but I have always been an LTM HMI user,” the cameraman testifies. “Their 12/18K lamp is the best instrument of its kind. It puts out more light and has a better spread, and that means I don’t need as many fixtures.”

The harsh shooting conditions on the asteroid set earned it an appropriately bleak nickname: “The Pit of Despair.” Bay credits this moniker to the special effects crew’s use of Rice Crispies cereal to help them whip up interstellar stormfronts. Soaked with water, the mushy foodstuff went moldy, resulting in a foul smell and sinus infections for almost the entire crew. “On top of that, the set was physically debilitating,” Bay says. “There were no level surfaces and no spots to be comfortable, so we just couldn’t shoot in there over a straight run. We ended up switching out with shooting in the shuttle interior, which we called ‘The Womb’ since it was relatively nice and calm.”

Armageddon s cast members were forced to endure their space suits throughout the entire “Pit” shoot. The helmet design is quite remarkable, featuring a large glass faceplate which curves across approximately 180 degrees of its surface. Bay notes, “We spent about $250,000 designing these helmets in order to provide radio communications and an optically clear glass dome, and to perfect an airflow system that would prevent fogging. The glass dome was actually built by the same company that builds NASA’s helmets.”

Added to the helmet was a specially built mini-lamp. “I knew Michael would want a blue helmet light,” Schwartzman says. “My first thought was that I could use a CTB-gelled MR-16 bulb, but those burn way too hot, so I went to LTM, hoping they could come up with something.” Their solution was a tiny 18-watt HMI bulb mounted in an MR-11 fixture, powered by a 12-volt battery built into the back of the lamp housing. “It created a beautiful light, and they made 50 of them for us,” the cameraman says, adding that the custom lamps were provided free of charge because the LTM company logo was prominently added to each. “I came to Michael with the idea that in the future, NASA might rely on corporate sponsorship. He replied, ‘If it gets me 50 helmet lights for free, I love the idea!’ All joking aside, though, LTM really came through for us in the crunch.

“The beauty of this for me was that if I needed to sneak in a 200-watt Par to light some specific detail, I could do it whenever I wanted to because it could be motivated by anybody’s helmet lamp. If I’d had to black out every single source I used, we’d still be shooting Armageddon today.”

The space suits weren’t just for show, however. The special effects department’s vicious artificial tempests showered the cast (and crew) with clouds of smoke and nitrogen gas, hail-like ice and grimy grit, so the protective helmets and padding were literally necessary for survival. Bay remembers, “There were times when 10 guys were operating these 100-mile-per-hour fans, big air movers, and machines shooting huge ice chunks through the air, and I’d hear Bruce Willis on the radio saying, ‘Knock it the f-off with the baseball-sized chunks of ice!’ They were just pelting him, and it would hurt like hell if you weren’t wearing a space suit.”

Mission Accomplished

After the main unit finished its work at Disney, Bay and his editing team, led by Mark Goldblatt, concentrated on cutting the picture at producer Jerry Bruckheimer’s complex located in Santa Monica. Throughout the show, the editors utilized North Hollywood-based Digital Editing Solutions’ dailies service and the Avid Film Composer system. DES’ direct film-to-digital format transfer produces a high-quality image and facilitates the cutting process by providing ready-to-use 9-gig Avid files complete with scene and take logs. DES simultaneously creates a tape version in whatever format is required, and can even burn off CD-ROM dailies for viewing on desktop or laptop computers.

Although Armageddon is constructed from an astonishing number of shots, Bay notes, “We were working in the land of big toys, which called for us to slow the pace down a bit to take it all in and make the film seem more epic.” Comparing this style to the amped-up feeling of The Rock, he offers, “Conceptually, The Rock was a ‘B’ idea. Armageddon is an ‘A’ idea. The Rock's story boils down to ‘a fanatic on an island.’ To make it seem more real, I hired classy actors to fill the roles — you believe Ed Harris — and gave it a story clock that moved at hyperspeed. That approach wouldn’t fit Armageddon because of the nature of the story; there’s just too much going on.”

Long after Armageddon wrapped, Bay was still shooting. After screening a 50-minute portion of the show at the Cannes Film Festival in May, the director photographed extra footage in the gothic French city of San Michele, and then jetted off to Istanbul, Turkey, and the Taj Mahal in India — in order to add a more global context to the disaster saga.

Assessing the ordeal of making Armageddon, Bay offers, “There’s a level of detail in these kinds of films that you take for granted, and I’ll never make another space movie again. But the picture also has some really tragic, emotional scenes that have made audiences cry, which is great. The film is a huge combination of visual, physical and dramatic elements, and I think it works.”

Despite the various trials he faced on Armageddon, Schwartzman contends that this shoot was far easier than The Rock. “On that show, we spent the first six weeks on Alcatraz, which was brutal,” he describes. “We never recovered, whereas on Armageddon, we all knew how to pace ourselves. I was no more exhausted on the last week of the show than I was on the third week.”

He credits gaffer Andy Ryan, rigging gaffer Jeff Soderberg, key grip Les Tomita, rigging key grip Jake Jones, operator Mitch Amundsen, B-camera/Steadicam operator David Emmerichs, first assistant Richard Mosier, second assistant Thom Lairson, B-camera first assistant Heather Page, B-camera second assistant Charles Katz, loader Dan McFadden and the rest of his crew for making the shoot run smoothly.

“This picture was unique in that we had an idea of how it should look,” Schwartzman concludes, “but discovered things as we went along. That can be hard on the assistant directors, but it makes for exciting filmmaking.”

Here, the cinematographer looks back on the production, 25 years later.