“Seventies Cinema” in AC

The magazine hit its stride while covering seminal films during one of movie history’s most innovative — and influential — decades.

Among movie scholars, it’s accepted wisdom that the 1970s represents one of cinema history’s finest eras — a decade filled with daring, iconoclastic motion pictures whose makers broke with convention to produce edgy work that both captured and questioned the zeitgeist.

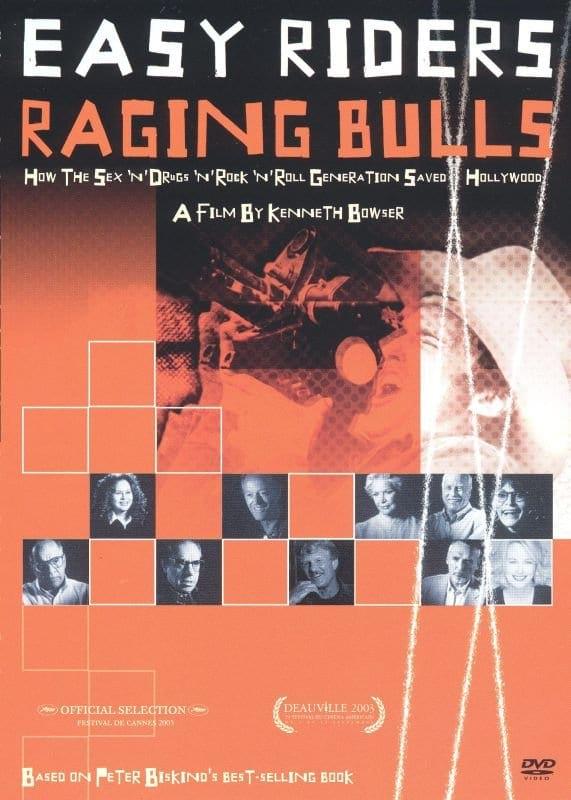

This artistic revolution had begun to take root in the mid-’60s, as director Martin Scorsese observes in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Peter Biskind’s in-depth chronicle of the key filmmakers who emerged to define Seventies Cinema: “When the movie factories were blown apart by television in the ’50s, there weren’t a bunch of people who said, ‘This is where we go now.’ People had no idea. You pushed here, and if it gave there, you slipped in. And as all that pushing and shoving was going on, the equipment was changing, getting smaller and easier to use. Then the Europeans emerged. Combine all those elements together, and suddenly by the mid-’60s, you had a major explosion.”

As the 1960s drew to a close, the major Hollywood studios were in dire financial shape. Possibly pondering the mid-’70s blockbuster Jaws while framing his thesis, Biskind writes, “The once-proud studio system, already a leaky vessel, was listing badly, and the conglomerates were circling beneath the chop, looking for dinner. Although Hollywood watchers looked on gloomily as studio after studio became no more than an appetizer for some company whose primary business was insurance, zinc mining, or funeral homes, there was a ray of sunshine. The same upheavals that had left the studios bruised and battered made room for fresh blood in the executive suites.”

Jaws director Steven Spielberg was one of the up-and-coming filmmakers who benefitted, as he explains in Easy Riders: “The ’70s was the first time that a kind of age restriction was lifted, and young people were allowed to come rushing in with all of their naïveté and their wisdom and all of the privileges of youth. It was just an avalanche of brave new ideas, which is why the ’70s was such a watershed.”

The situation helped break a rolling wave of talented filmmakers, both in front of and behind the camera. During the ’70s, directors like Hal Ashby, Peter Bogdanovich, John Boorman, Michael Cimino, Francis Ford Coppola, William Friedkin, George Roy Hill, Norman Jewison, George Lucas, John Milius, Mike Nichols, Alan Pakula, Roman Polanski, Michael Ritchie, John Schlesinger and Spielberg would all appear in AC articles, detailing their collaborations with ASC cinematographers such as John Alonzo, Conrad L. Hall, Victor J. Kemper, Laszlo Kovacs, Giuseppe Rotunno, Owen Roizman, Robert Surtees, Haskell Wexler, Gordon Willis and Vilmos Zsigmond.

(Strangely, Scorsese himself made only a cameo appearance in the magazine’s pages during the Seventies, with a brief mention in its October 1970 coverage of the music documentary Woodstock, on which he and his future feature editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, served as assistant directors and editors.)

Aptly enough, the very first issue of American Cinematographer published during the Seventies, in January 1970, featured editor Herb A. Lightman’s article “The Filming of Medium Cool,” a film “written, co-produced and photographed by Haskell Wexler, ASC, which represents the applications of cinéma-vérité technique at its best.”

Always a forward-thinking firebrand, Wexler commented, “Since I was also the cameraman, I decided to use the simplest lighting system I could think of, so that if I wanted to do a 360-degree pan around a room I wouldn’t have to re-light the set. For this reason, I used what was basically bounce light for photographing much of the picture — adding one or two hotter lights to snap things up a bit. However, with the exception of one sequence where 1,000-watt quartz lights were used, the lamps I employed were never larger than 750 watts.

“When you’re working with non-professionals you can’t spook them with the equipment — a lot of floor lamps, century stands and all that,” he added. “It’s bad enough that you have a camera and a bunch of guys who are stretching tapes and blocking doors, so it’s best to keep the lighting equipment as unobtrusive as possible. You sometimes have to sacrifice a bit of photographic quality in this kind of compromise, but the performance is more important.”

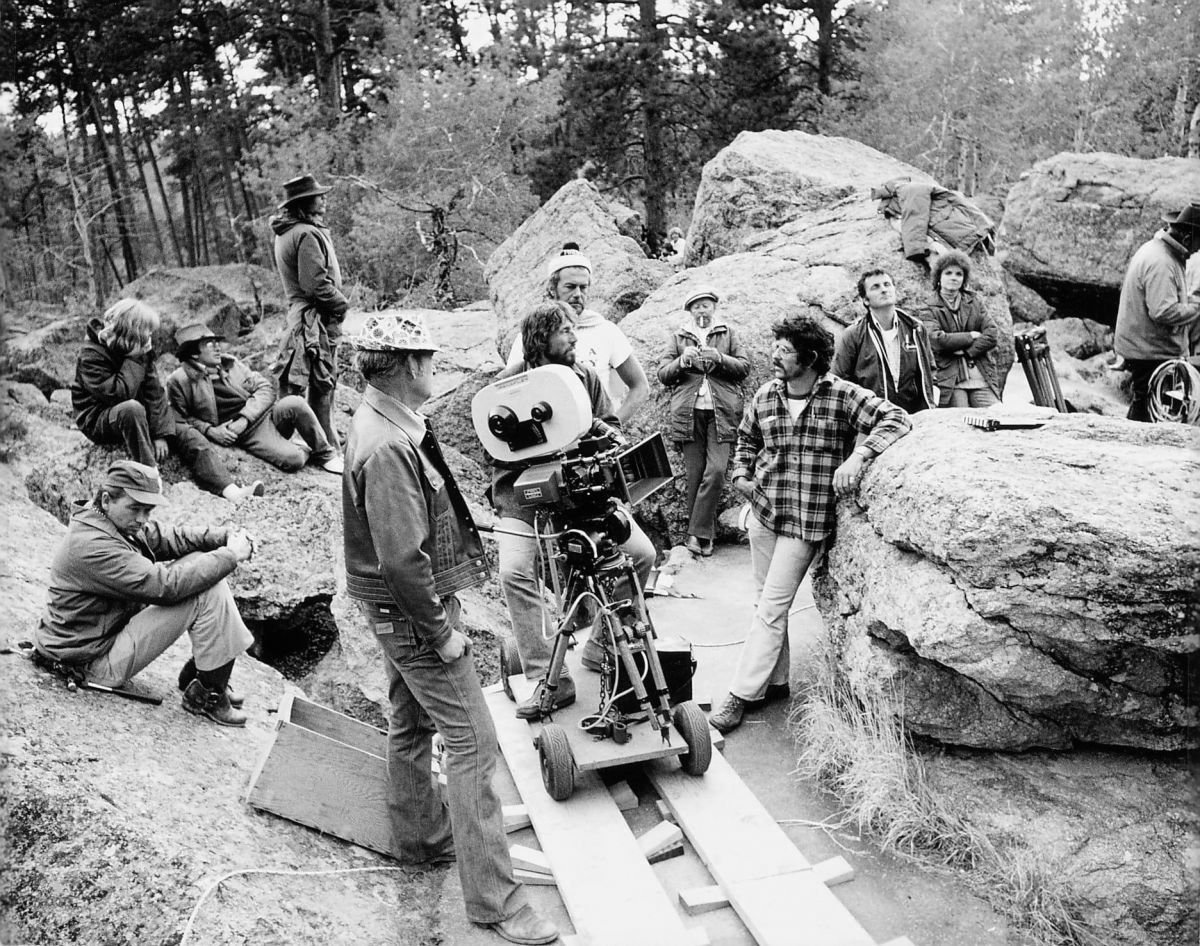

In May of 1970, the magazine provided insights from Wexler’s close friend Conrad L. Hall, ASC about his work on Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, a postmodern, existential take on the Western. As Hall told Lightman, “The objective in the filming was to have this inexorable envelopment of modern technology come over as some sort of symbolic thing, so that the law and advancing technology would be evidenced as symbols, rather than actual, recognizable elements of society. We had to do something visually to get this idea across — yet, in terms of action, we still had to have the traditional chase between the desperadoes and the law.”

The creative approach, Hall notes, was to have the outlaws Butch and Sundance doggedly pursued by a faceless, distant “Superposse” that would track them with steady, relentless determination. To accomplish the effect, Hall shot the Superposse with Panavision’s 50mm-500mm Panazoom, racked out all the way to “take advantage of things like heat-wave distortion to make the figures wispy, unrecognizable, yet somehow menacing… I tried to enhance this impression photographically by keeping them at a distance, enveloping them with dust, distorting them with heat waves and shooting them through out-of-focus leaves and such, in order to have them come over as symbolic rather than real beings.”

As the decade progressed, the magazine featured coverage of major cultural events of the day, including the Concert for Bangladesh, President Richard Nixon’s visit to China, the Olympics, the Royal Wedding of Capt. Mark Phillips and Princess Anne, and the 1974 World Cup.

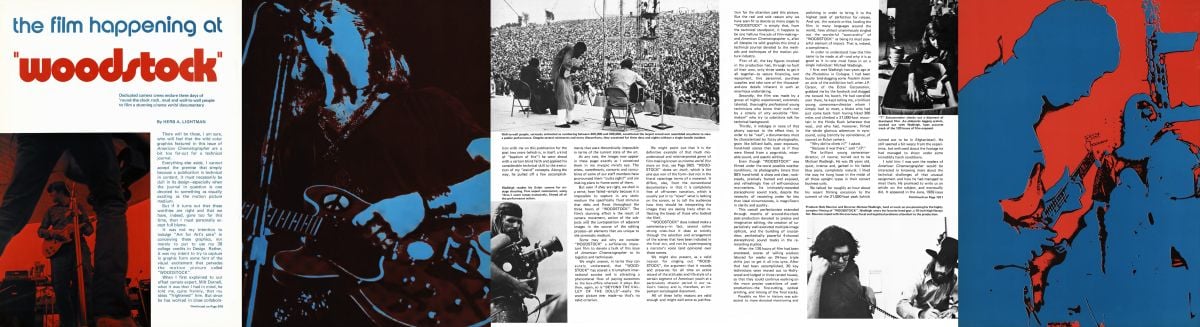

One of the biggest of these “happenings” was the Woodstock music festival. The magazine gave Michael Wadleigh’s eponymous documentary blanket coverage with four articles that appeared in the October 1970 issue. In one of them, Wadleigh explains his strategy for covering the historic concert: “My objective was to hire the very best cameramen/directors that I could, give them a nice free hand, and just coordinate the whole thing. We hired people who are expert at hand-held filming — big, solid guys who can really hold a camera steady. I’m not one of those people who believe everything should be hand-held — that’s nonsense. But in a concert situation, with all that rock movement going on and the amount of shooting that has to be done right in the midst of crowds, you can’t very well set up a tripod. You find that you’re always in the wrong place, or someone gets in front of the camera, or trips over the tripod. You’re left with no choice but to hand-hold most of it — and that’s what we did.”

Lightman, AC’s editor throughout the ’70s, felt obliged to explain the magazine’s use of trippy color schemes in its Woodstock layouts: “There will be those, I am sure, who will feel that the wild color graphics featured in this issue of American Cinematographer are a bit too far-out for a technical journal. Everything else aside, I cannot accept the premise that simply because a publication is technical in content, it must necessarily be dull in its design — especially when the journal in question is one devoted to something as visually exciting as the motion-picture medium. But if it turns out that these worthies are right and that we have, indeed, gone too far this time, then I must personally accept full blame.”

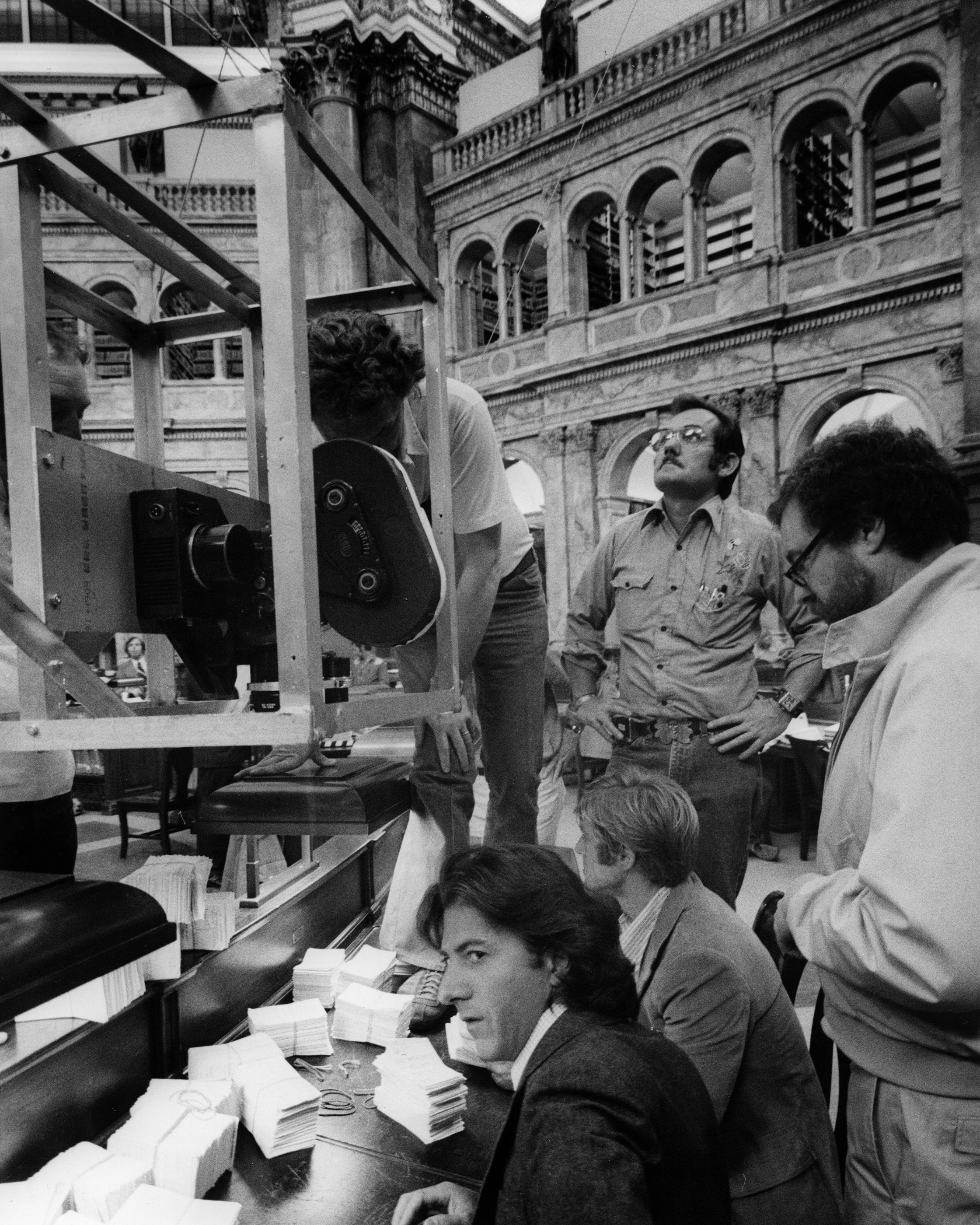

Some of the most oft-referenced articles in AC are those detailing the work of Gordon Willis, ASC, who had a very good decade indeed during the 1970s — despite the fact that studio executives often felt he had gone too far with the dark, penumbral imagery he often favored. In addition to covering his timeless work with Coppola on The Godfather (June ’71), the magazine spotlighted the cinematographer’s contributions to Alan Pakula’s All the President’s Men (May ’75) and published two-part coverage of an American Film Institute seminar featuring Willis (Sept. and Oct. ’78).

Discussing the famous look he fashioned for The Godfather, Willis told interviewer Greg Steele, “I felt that the film should be brown and black in feeling, and that occasionally it should be hanging on the edge from the standpoint of what you see and what you don’t see. A lot of cameramen work to increase the quality of an image, but in this specific case I’m working to decrease it. Most cameramen work to make the image as structurally sound and smooth as possible, but it’s been my personal feeling that this isn’t the best way to handle a contemporary story — and now that I’ve thought about it, I’m convinced that it’s absolutely the wrong way to photograph a period story.”

Willis noted, however, that this approach would not be carried throughout the entire picture: “It wouldn’t be right to do that, because the action of the story moves from New York to Hollywood to Sicily. This brown, sort of broken-down quality I’ve described relates to the New York sequences, but not to those that take place in Hollywood. I plan to emphasize the contrast between the two locales by giving the Hollywood sequences a cleaner, crisper, sort of West Coasty, California quality — which should be a bright, hard image. In juxtaposing the two — cutting from New York to California — there should be a very definitive difference in relation to the atmosphere and the people.” Willis also fashioned a warmer look for the Sicily scenes, and extended his use of top light throughout the picture — a highly unusual tactic at the time.

Another of the most lauded films of the 1970s was Chinatown, which initially paired legendary ASC member Stanley Cortez with Polish director Roman Polanski. The strategies Cortez employed were not to Polanski’s taste, however, and after a few weeks of work Polanski replaced him with John A. Alonzo, ASC, whose work on the picture earned him an Academy Award nomination.

“Some people after viewing Chinatown come away with the idea that the picture was shot entirely on location,” Alonzo told AC in May 1975, before tipping his cap to the work of renowned production designer Richard Sylbert, whose art and set decoration also earned an Oscar nomination. “The truth is that a great deal of it was filmed on the soundstage. I’ve never figured out the percentages, but I would say that approximately 65 percent was shot on the stage. The interior of the Hall of Records, the Department of Water and Power, Gittes’ living rooms, the interiors of that wonderful old house in Pasadena — all these were studio sets.”

One shot made on location was the film’s famous ending, which Polanski improvised on set. Alonzo recalled, “At the last minute, so to speak, an interesting thing happened. Roman suddenly said: ‘I want a crane.’ I said: ‘You want a crane?’ And he said: ‘Yes, I’ve just figured out how to end this picture.’ And it appeared that he had, right then and there on the spot.

“He said: ‘In the sequence, up to this point, Faye Dunaway has been shot. You see the police officer fire a shot and you hear the car stop and, obviously, [Evelyn Mulwray] is dead, because you hear the horn blowing. Now, where do we go from there? Well, here’s the idea: we go hand-held and all the actors come toward the camera and you do a news-documentary kind of thing. You whip-pan over to show Faye for just a brief moment. I want to see the destruction of her eye. Then the police detective sits her up and you pan around onto him, then onto Nicholson, then back to the detective, then back to Nicholson as he’s pulled away by his two friends. Then I want the camera to climb 27 feet into the air — hand-held.’

“When he told me that, I said: ‘Roman, you’re contriving a shot. You’re contriving it because you don’t know how to end the picture. You’re performing cinematic gymnastics.’ “I was kidding him about it, but he said: ‘No, no, no — it really fits. This is how it has to work…’”

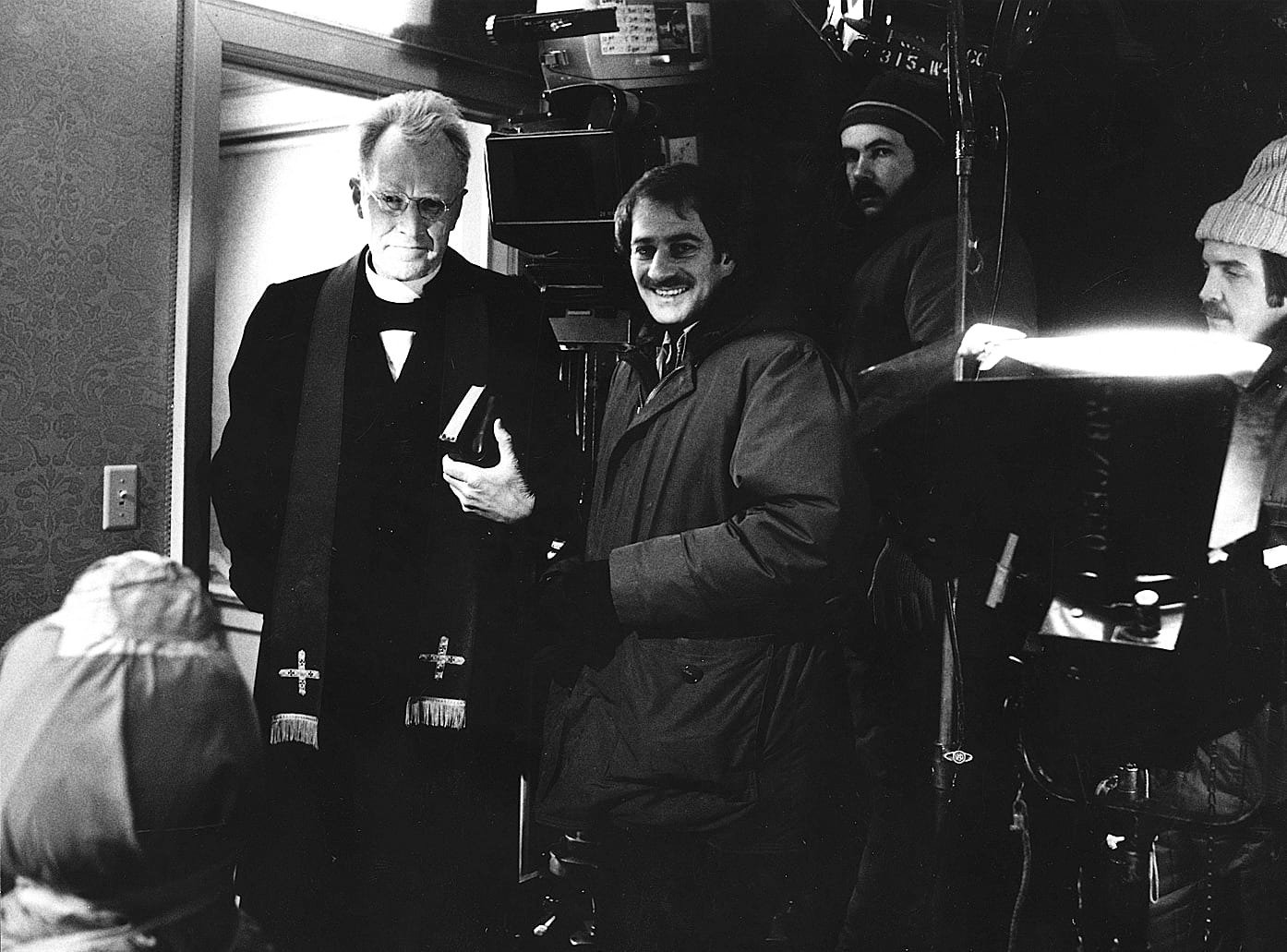

Another cinematographer who made a lasting mark during the 1970s was Owen Roizman, ASC, whose iconic work in The French Connection, The Exorcist and Network was covered.

Discussing The Exorcist in the February 1974 issue, Roizman recalled his experience while filming what would become one of the most famous shots of the Seventies, on location in Washington, D.C.: “We shot night exteriors in Georgetown, and the trickiest one was the scene where the Exorcist himself arrives at the house. It’s late at night and the shot starts with the camera pointing down the desolate, foggy street. Two headlights appear out of the fog and we see that they’re coming from a taxicab that swings around in front of the house. The priest gets out and stands in the bright glow coming from the little girl’s bedroom window, [but] it was difficult to get that bright of a glow from a shaded window, and we also had to hold a fog effect all the way down the street. Of course — wouldn’t you know — just as we were ready to shoot, the wind came up, which made it more difficult to keep the fog settled in. But we shot as fast as we could and managed to get the scene.” (For Roizman’s observations about another key sequence in The Exorcist, see “The Power of Christ Compels You!” further down the page)

Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC was also on a roll during the ’70s, and his stunning achievements in Deliverance (AC Aug. ’71), The Long Goodbye (AC March ’73), The Deer Hunter (AC Oct. ’78) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (AC Jan. ’78 and Feb. ’78) were dutifully chronicled.

In an article about Close Encounters that carries his byline, Zsigmond recalls shooting the famous climax of Spielberg’s picture in Mobile, Alabama, within a huge hangar representing the UFO landing site at Devil’s Tower in Wyoming: “Probably the most effective lighting in the picture — or, at least, my favorite — is that used to create the dazzling effect when the Mother Ship opens. You get the feeling that there are millions and millions of footcandles of light coming from the spaceship. In order to create that effect, our art director made the opening of the ship out of mirrors, and all we had to find out was where to put our HMI lights. We used only four HMI spotlights to get the effect. These were the first scenes we shot on the big set and nobody could really tell how the effect was going to look on film. We shot it on 35mm negative, using high-speed lenses, with an exposure between T/1.5 and T/1.7.

makes contact with the human race in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977).

“What made the light rays show up in the fog? I think it was mostly the breaks in the mirrors, or even the dirt spots on the mirrors, the footprints. Those elements created a sort of pattern for the light. I think that in order to show light rays, you have to have a discontinuation of the light here and there. If you don’t have those breaks (or those dirt spots in the mirrors) then what you have is actually an even spotlight effect. In this case, our spotlights were beamed in from various angles, and the rays were reflected from the mirrors at angles complementary to those. The result is light bouncing around from a variety of angles to create a dazzling effect.”

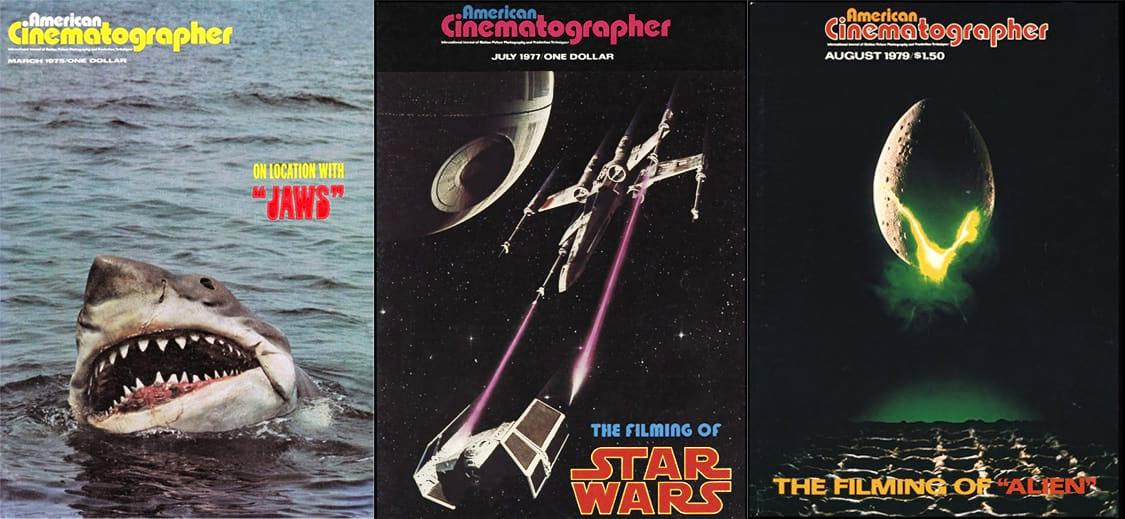

Prior to Close Encounters, Spielberg had earned a March 1975 cover for Jaws, shot by Bill Butler, ASC. Years later, Spielberg told American Cinematographer, “One of the biggest honors I’ve ever received was when the magazine put [Jaws] on the cover back in the Seventies. Everybody has their own measure of success; for me, it was getting the cover of AC.”

glide by an underwater observation cage while shooting Jaws.

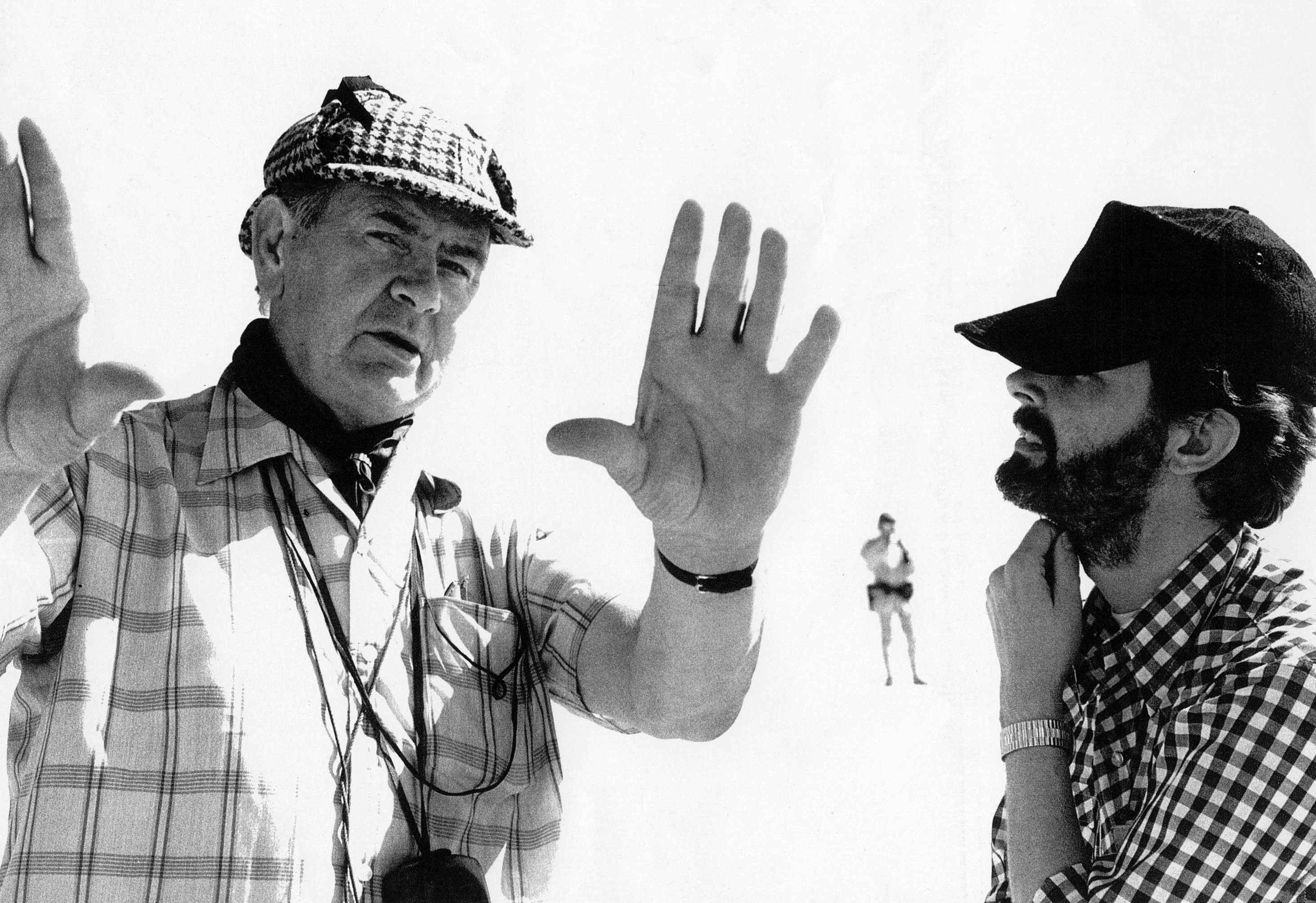

Spielberg’s coveted cover was accompanied by an article written by Mik Cribben, who was welcomed onto the production’s location sets on the Massachusetts island of Martha’s Vineyard, just south of Cape Cod. Cribben provides a vivid, firsthand account of the filmmakers shooting a climactic scene in which the Great White launches itself from the ocean and lands on the poop deck of the Orca, the fishing boat skippered by the flinty shark hunter Quint (Robert Shaw): “The whole afternoon was spent in preparing the shot, and as it approached 5:30, the end of the day, it looked like they were never going to get the shot off, but just before 5:30 everything came together and Steve Spielberg decided to go for the shot. He called ‘Action,’ and he got a lot more than he called for. Steve, Roy Scheider, Dick Butler (Robert Shaw’s stuntman and no relation to Bill), Bill Butler, three camera crews and three cameras were all aboard the [Orca]. When the shark came down on the boat it looked like an explosion and for thirty seconds all hell broke loose. The weight of the shark caused the boat to fill up with too much water and it started to go down like a stone. I saw Roy Scheider dive into a mass of nail-filled pieces of wood splintered from the transom by the shark and did not see him come up for a long time. Other people were jumping clear of the boat and people on other boats were rushing to help them. There was much confusion and people were shouting, ‘Save the camera!’ and ‘Save the lights!’

cinematographer Bill Butler, ASC soak up the scene while shooting off Martha’s Vineyard.

“As the boat started to sink, it also started to tip over. Some crew members on the work boat, the Ruddy Duck, also dove clear of their boat when they saw the 30-foot mast of the Orca coming down on them like a tall timber. Fortunately the Orca was attached to a crane on one of the boats, the Whitefoot, and this kept the Orca from sinking or tilting too much. To top it off, a sudden squall came up and it started to storm. After it was all over, no one was seriously hurt, but the number-one camera had been submerged and the magazine with the hard-earned footage was filled with water. Everyone thought the footage was lost and the whole thing would have to be done again, but Bill Butler had the magazine immediately taken to shore and fresh water was exchanged for the brine. The magazine was carried in someone’s lap on the next plane to New York and was processed by Technicolor in New York under the supervision of Otto Paoloni that night. They got the results the next morning. The footage was fine. No second take was made, and that is the footage that the public will see in the film.”

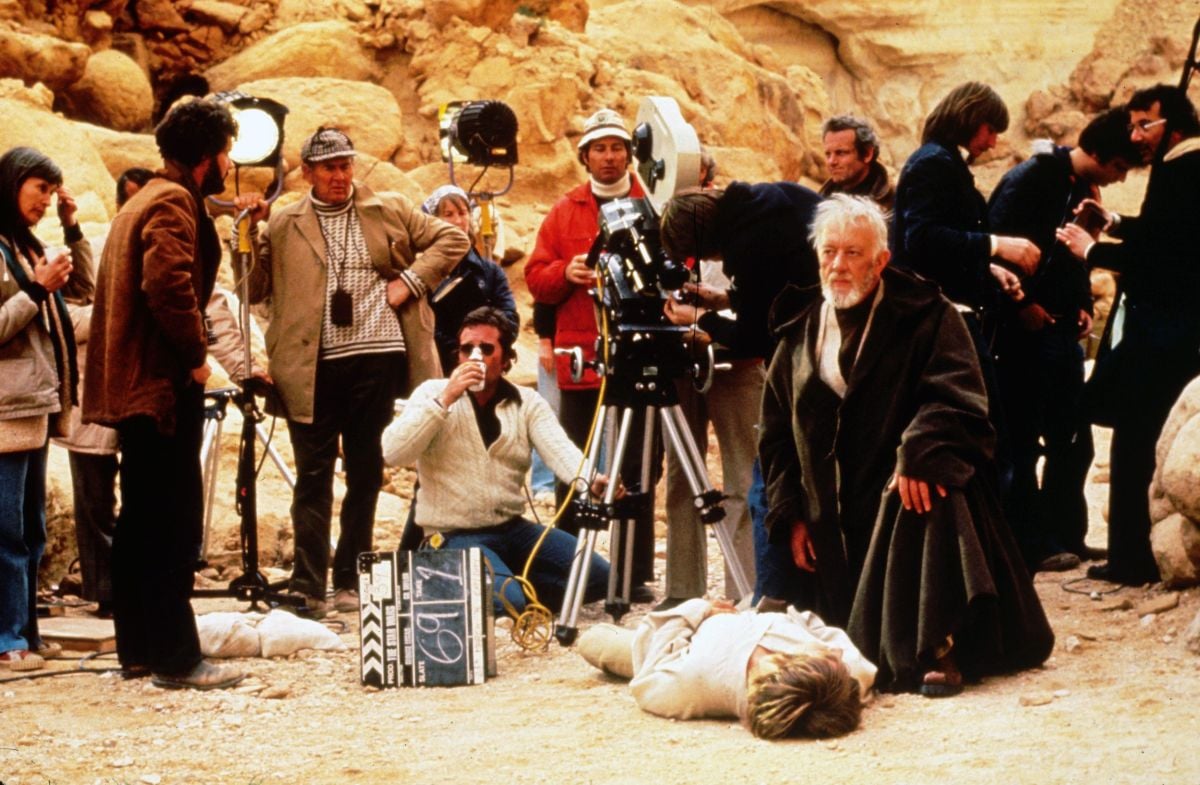

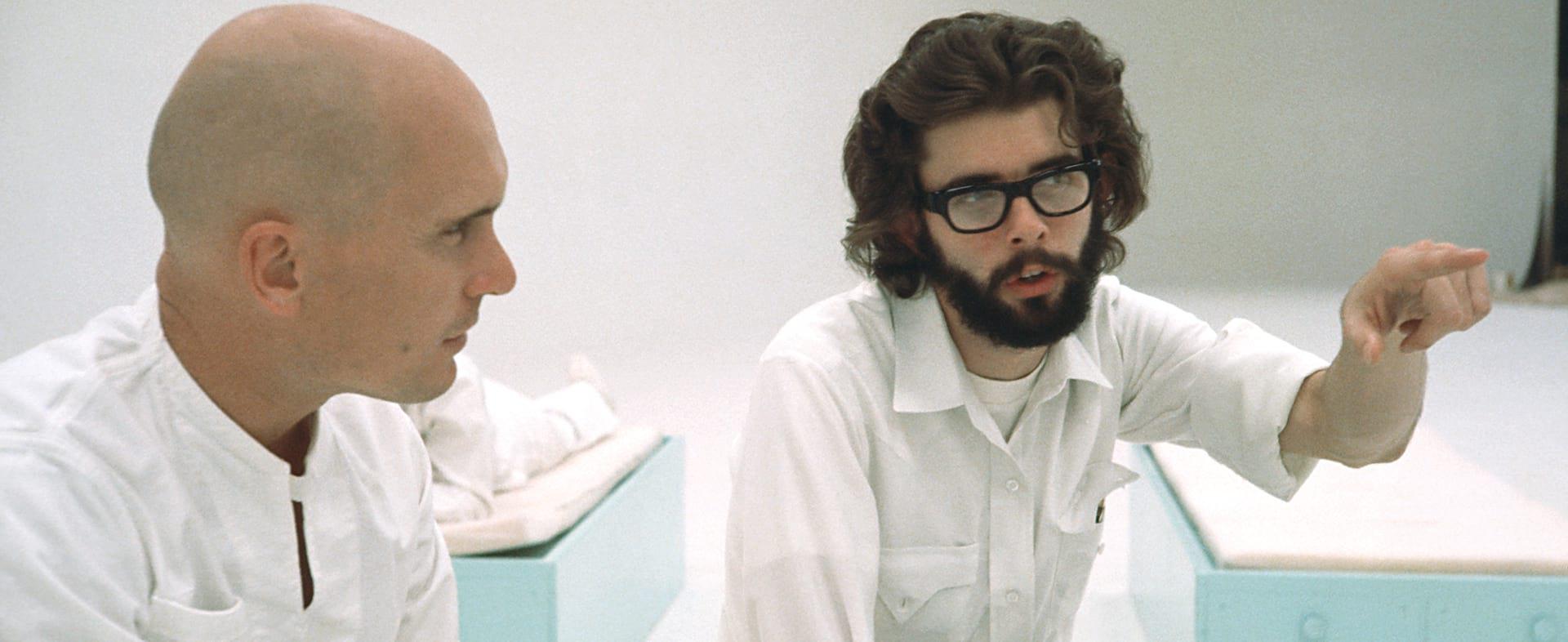

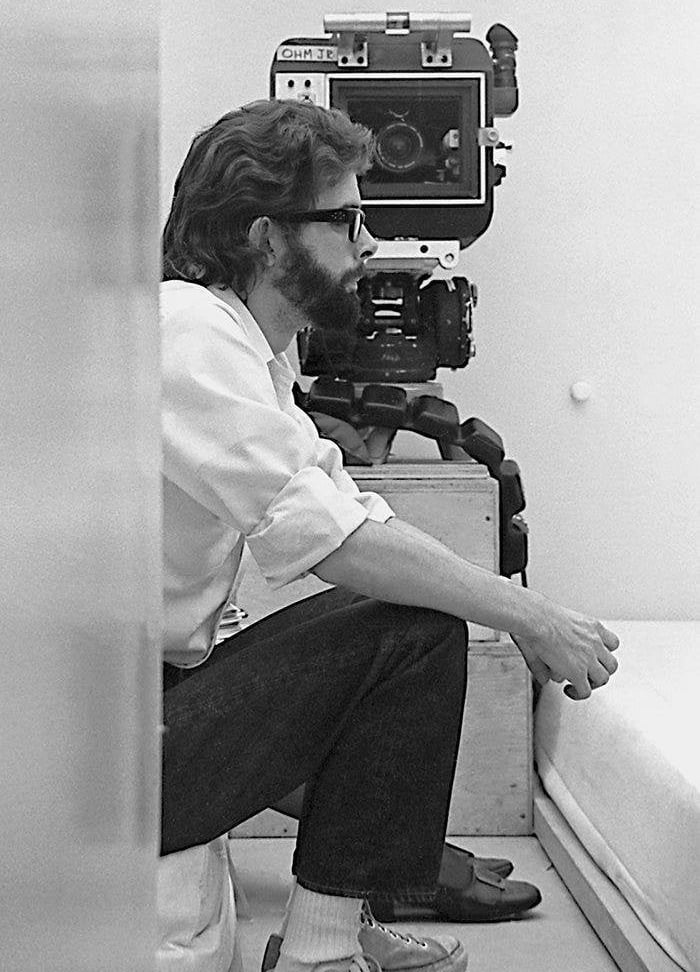

A close friend of Spielberg’s, George Lucas, would also vault to lasting, worldwide prominence during the 1970s. Lucas made a striking debut with his independent, dystopian sci-fi feature THX-1138, and the young director wrote about his project in the October 1971 issue of AC, which had a special focus on filmmaking in San Francisco. In touting the promise of THX-1138, the magazine noted, “Though financed and released by Warner Bros., the film, in its creative concept and execution, was in no way a ‘major studio production.’ On the contrary, it was totally the product of American Zoetrope, the San Francisco-based filmmaking ‘commune,’ founded and funded by Francis Ford Coppola for the purpose of attracting, encouraging and utilizing talented young film technicians new to the industry.” (In the same issue, American Zoetrope was the subject of a separate article penned by its general manager, Christopher Pearce.)

Lucas’ cinematographers on the production were Albert Kihn and David Myers, but additional footage was shot by an uncreditied Haskell Wexler, ASC, who became friends with Lucas during the latter’s undergrad days at USC and would help shoot his breakthrough film, American Graffiti (1973). Robert Duvall stars as THX, who lives in a dystopian future. After being arrested, he is imprisoned in a white void and tortured by android police officers.

Summarizing his vision for THX-1138, Lucas wrote, “My primary concept in approaching the production of THX 1138 was to make a kind of cinema verité film of the future — something that would look like a documentary crew had made a film about some character in a time yet to come.” He added, “At the same time … I wanted the picture to look slick and professional, in terms of cinematic technique. I felt that the realism of the film's content would be enhanced by having the actors and their surroundings look slightly scruffy, even a little bit dirty, as they might well look in the society depicted.”

Later in the decade, of course, Lucas would bring elements of this aesthetic to a little film called Star Wars — which received outstanding coverage of its cinematography, miniatures, mechanical special effects, composite optical and photographic effects, and the Dolby sound system used for recording — in the July 1977 issue of AC.

Ridley Scott would present a similarly grungy vision of the future with Alien, the first feature photogrphed by Scott’s frequent cinematographer on commercials, Derek Vanlint, covered in the Aug. ’79 issue.

Throughout the 1970s, AC had a taste for covering the “disaster movies” that were in vogue during the era, which produced lavishly detailed articles about pictures such as The Poseidon Adventure (written up in Sept. ’72), Earthquake, presented in glorious “Sensurround” (Nov. ’74), The Towering Inferno (Feb. ’75), The Hindenburg (Jan. ’76), Airport ’77 (May ’77), Hurricane (March ’79), The Concorde — Airport ’79 (Aug. ’79) and Meteor (Dec. ’79).

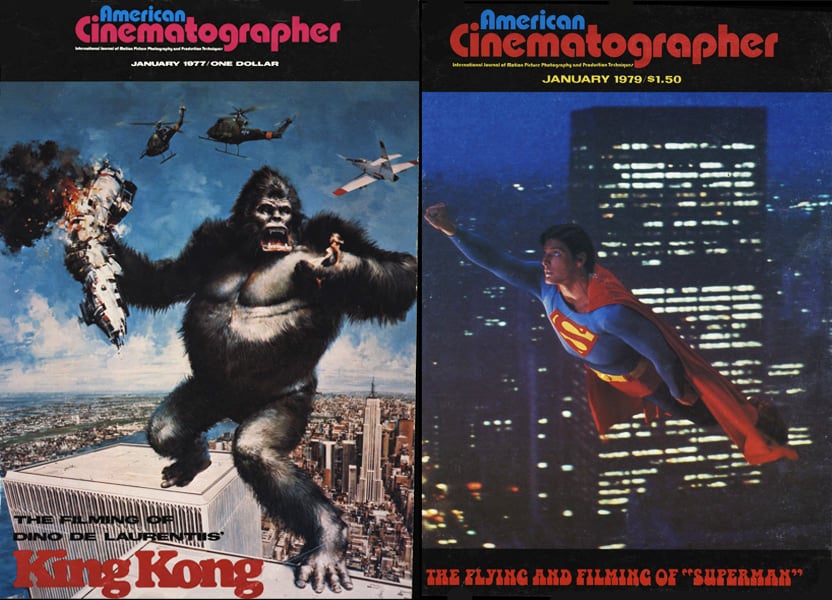

Escapism was the order of the day in coverage of the James Bond movies On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (March ’70), The Spy Who Loved Me (May ’77 and Feb. ’79) and Moonraker (Oct. ’79). (“A cameraman must have a high degree of technical skill, acrobatic agility, grim determination and a generous supply of just plain ‘guts’ to photograph the exploits of James Bond,” one article declared.) King Kong had a whole issue to himself in Feb. 1977, as did Superman (Jan. ’79). Lighter fare that earned scrutiny included comedies like Young Frankenstein (July ’74), The Return of the Pink Panther (April ’75) and Love at First Bite (Feb. ’79), along with the occasional musical, such as Fiddler on the Roof (Dec. ’70), Grease (Aug. ’78) and The Muppet Movie (July ’79).

War movies were covered less frequently than they had been during the 1960s, although the magazine published articles on a few that were noteworthy, such as Tora! Tora! Tora! (Feb. ’71), A Bridge Too Far (April ’77), Zulu Dawn (Feb. ’79) and Spielberg’s comedic epic 1941 (surveyed with multiple articles in Dec. ’79).

Television shows occasionally made the cut, evidenced by articles on The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau (Sept. ’70); The Odd Couple (Oct. ’71, with ASC member Lester Shorr explaining how the production had gone “cordless”); the cop series The New Centurions, shot by Ralph Woolsey, ASC (Sept. ’72); An American Family, a very early forerunner of today’s reality-TV shows (May ’73); and The Streets of San Francisco, shot by Jacques Marquette, ASC (Aug. ’75).

Still, it’s the magazine’s highly detailed coverage of the era’s most famous and revered films that makes American Cinematographer issues from the ’70s so compelling to read. Other standout titles examined during the decade include Patton (Aug. ’70), shot in the Dimension-150 65mm format by Fred J. Koenekamp, ASC; The Candidate (Sept. ’72), framed by Victor J. Kemper, ASC, who also shot a run of Seventies classics that included The Friends of Eddie Coyle, The Gambler, Dog Day Afternoon and Slap Shot; The Last Picture Show (Jan. ’72), which showcased the evocative cinematography of ASC member Robert Surtees, whose crisp black-and-white imagery brought the picture “a dark brooding intensity that delineates with graphic precision the hopelessness of a dying small town”; and Barry Lyndon (March ’76), featuring candlelit scenes that famously required John Alcott, BSC to employ specially modified Zeiss 50mm and 36.5mm f/0.7 lenses.

Like the era itself, these articles have left a lasting mark, and are well worth revisiting for anyone who enjoys watching, discussing, or thinking about movies.

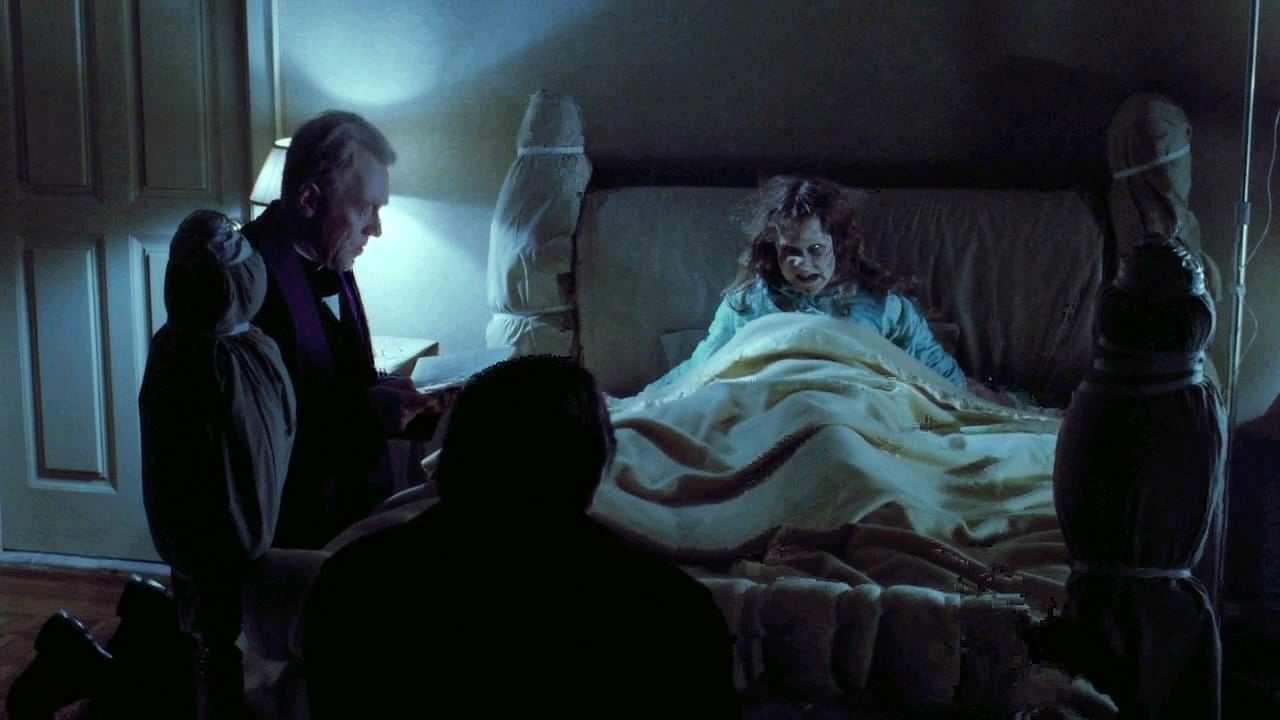

From “The Exorcist — How It Was Filmed”

AC February 1974

Recalls Owen Roizman, ASC: “The exorcism sequence did involve some very special problems. One of these stemmed from the fact that in the story anyone who walks into the child’s room becomes extremely cold and develops a chill. The only way you can really show that kind of cold is to be able to see the breath of the characters—and the only way to see this breath is to actually have them in a very cold room. For this reason, the child’s bedroom was duplicated and built inside a ‘cocoon’ — as they called it — which was refrigerated, generally to about 20 degrees below zero. We tried it first at just below freezing (about 25 degrees) and you could see some breath, but it really wasn’t enough, and as soon as the lights were turned on the heat took care of the cold so quickly that we couldn't even make a take. We found out during the test period that this wouldn't work, so we went back to the drawing board. A system was developed that could refrigerate the room quickly to any temperature from zero to 20 below. The breath showed up fine at zero, but Friedkin wanted the actors to really feel the cold because he felt that would help their acting. An actor on his knees for 15 minutes at 20 below zero is really going to feel cold.”

Miller) attempt to drive the demon Pazuzu

from the body of young Regan (Linda Blair) in

The Exorcist.

The frigid conditions also helped the filmmakers sell the illusion for one of the movie’s most infamous moments, when the possessed Regan’s head twists 360 degrees. Noting that the special-effects crew was struggling to create a realistic effect with the dummy used in the shot, Roizman remembers, “As we were looking at the dummy in bed in the cold room, I said — as a joke, actually— ‘Wouldn’t it be great if the dummy had some frost on its breath?’ Everybody looked at me, and the next thing you knew, they were working on it. When they put that element in, it looked terrific. It was that one extra realistic touch that made the effect work.”

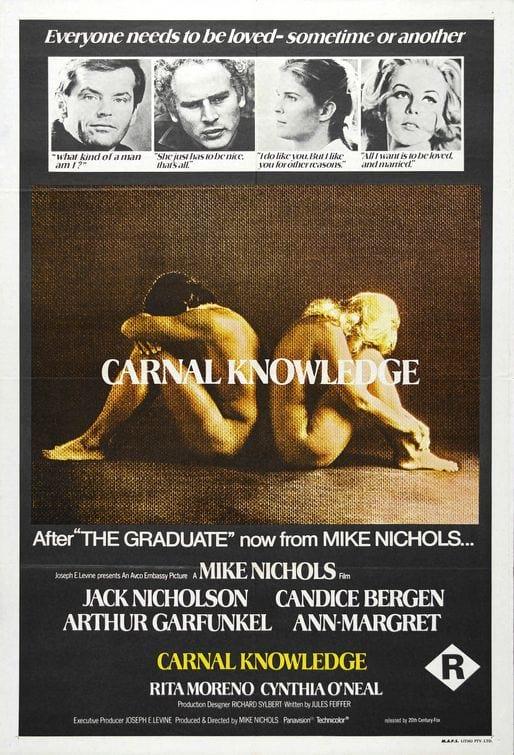

From “On Location With Carnal Knowledge”

AC Jan. 1971

AC editor Herb A. Lightman went on set with director Mike Nichols and cinematographer Giuseppe “Peppino” Rotunno, ASC, AIC during production of Carnal Knowledge and came away laughing after an encounter with one of the film’s stars, Candice Bergen:

“In reference, apparently, to some private joke, Nichols keeps calling her ‘Bugs’ and she responds with a most un-movie-starish good humor. Between set-ups Peppino introduces me to the lady, explaining that I am the editor of the ASC journal. Innocently he asks her if she knows what ‘ASC’ stands for.

“‘Of course,’ she replies. ‘My father’s a member of it.’”

“And so he is. Famed comedian Edgar Bergen has been an associate member of the Society for many years. At a recent ASC dinner meeting he convulsed the crowd by remarking: ‘My daughter, Candice, thinks I’m pretty square. She says that if I ever took LSD I’d probably see Lawrence Welk.’”

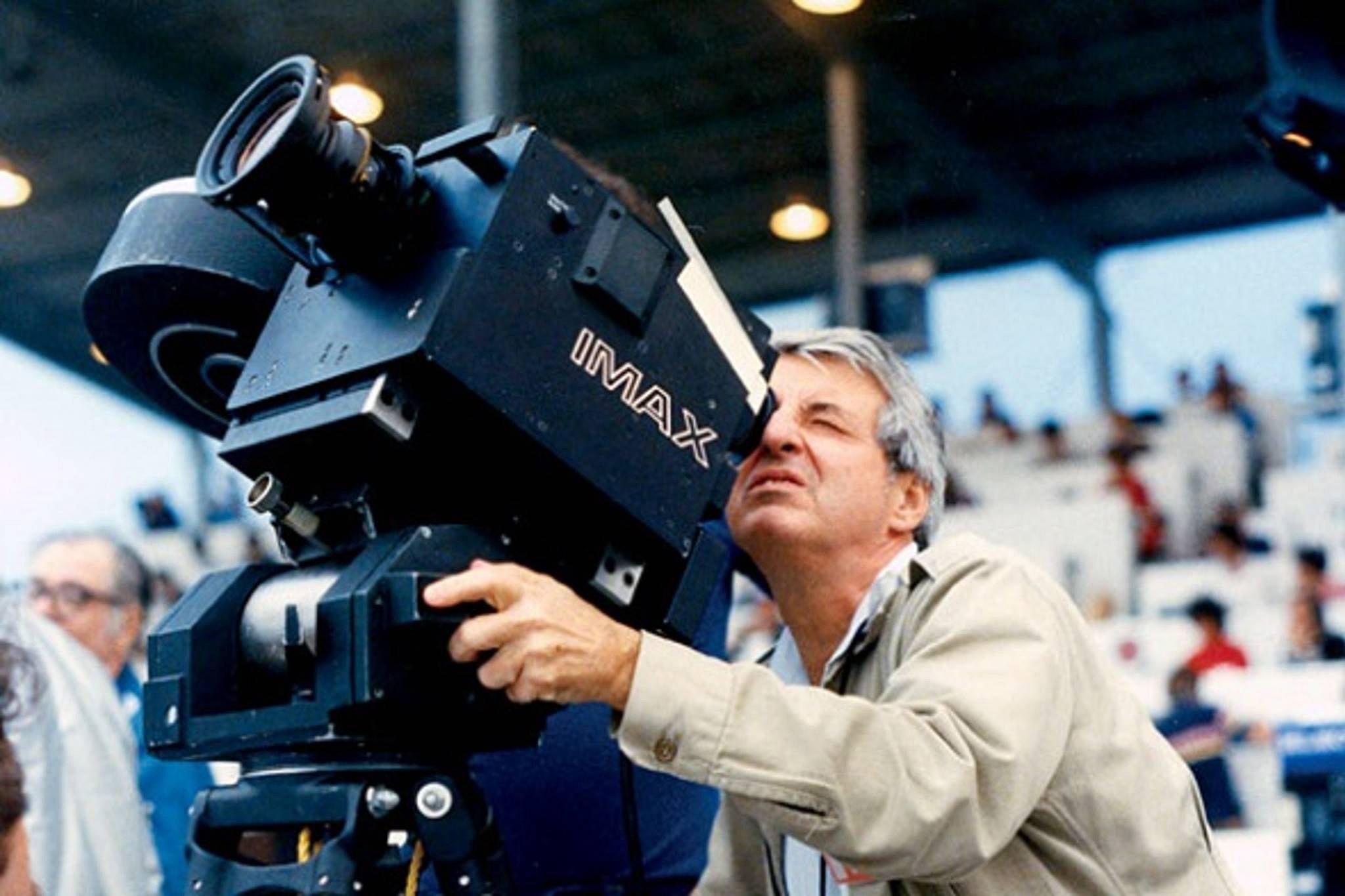

From “The IMAX System”

AC August 1970

with one of his company’s large-format cameras.

In 1993, the Canadian filmmaker and inventor

became a Member of the Order of Canada.

After attending Expo ’70, a world’s fair held in Suita, Osaka Prefecture, Japan, and stopping by the Fuji Group pavilion, the magazine provided an in-depth technical report on the world’s largest motion-picture format:

“Whether or not IMAX will prove economically feasible for general use in feature filming is something which will have to be decided by those concerned with the fiscal aspects of motion picture production and distribution. Our interest in presenting a comprehensive rundown on IMAX arises solely from the fact that it is, technically, a totally new and unique film format involving the design of compatible camera and projection systems from scratch. As such, it constitutes an important technical breakthrough in that it solves heretofore insoluble problems inherent to the concept of ultra-large film formats.”

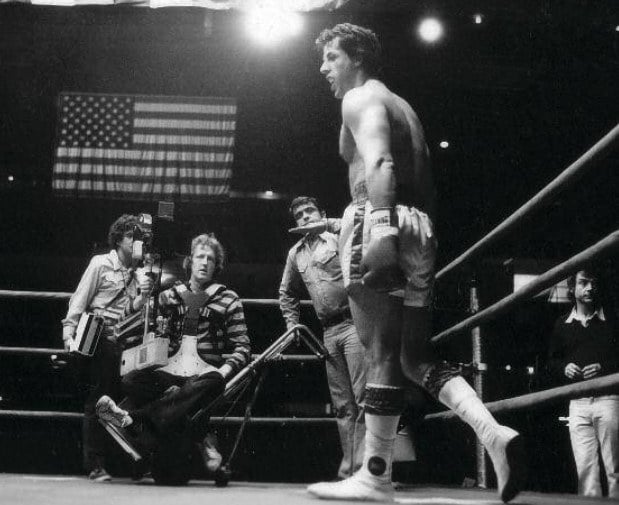

The Introduction of the Steadicam

AC July 1976

Several reports in this issue herald the arrival of the groundbreaking Steadicam-35 system, invented by ASC associate Garrett Brown. Ed DiGiulio of Cinema Products Corp. detailed the system’s design and capabilities in a piece titled “Steadicam-35: A Revolutionary New Concept in Camera Stabilization,” and AC editor Herb A. filed a report from the 9th Motion Picture Seminar of the Northwest in Seattle, providing an eyewitness account of Brown demonstrating his invention, “as he gallops about the stage to illustrate its incredible versatility. As proof of the pudding, he shows clips from recent features utilizing the device, including Bound for Glory, Marathon Man and Rocky. This part of the program turns out to be a real conversation piece and the hit of the show.”

In the same issue, an article titled “First Feature Use of Steadicam-35 on Bound for Glory” offers the hands-on observations of cinematographer Haskell Wexler, ASC: “I used it a number of times. The most spectacular usage was a combination shot which started with the camera high up on a Chapman crane to show a huge camp of migrants in the Thirties, poor people who were camped out in a sort of shantytown. The camera craned down to find David Carradine, who plays Woody Guthrie, sitting on an old car. He gets up off the car as the camera crane reaches ground level and the cameraman steps off the crane with the Steadicam in hand and follows Carradine underneath tents and through narrow passageways and crowds of people until he reaches another actor. They then have a scene where they back through more crowds of people. The camera moves as if it has no limitations, which, in a sense, it doesn’t have, because it travels over rough terrain where you couldn’t lay dolly tracks — and even if you could lay dolly tracks, they would appear in the picture. It’s quite spectacular. We used it in a number of other places where it was impossible to lay tracks, but where we wanted some fast movement.

“Usually when a new device comes out there are overstatements. People say: ‘This is the greatest thing ever! This is a breakthrough! It will change the way motion pictures are made!’ But I do think that this particular device will significantly increase the fluidity of the camera. It will, perhaps, be overused until people settle down to knowing how and where to use it, but it definitely is an exciting new working tool.”