The Evolving Art of Visual Effects

The increasing incorporation of visual effects into the production process yields partnerships between cinematographers and VFX supervisors that are more intertwined than ever before.

Introduction by AC Editor-in-Chief Stephen Pizzello

The relationship between cinematographers and visual-effects experts has been a crucial one throughout the history of cinema. Smooth integration of the magic created by both of these key filmmaking positions is critical to the believability of the action depicted onscreen, whether the effects involve creating entire worlds (as seen in the Avatar series), a spectacular space battle (a continual progression from the groundbreaking, iconic sequences of the original Star Wars trilogy), a living creature (e.g., the bear that mauls Hugh Glass in The Revenant), or more invisible “every day” elements (such as the very persuasive driving scenes in Mank, or the racing sequences in Ford v Ferrari).

Of course, as technology evolves — which it does on a regular basis in the filmmaking universe — key collaborative relationships can also change. In recent years, according to cinematographers and crewmembers supervising other departments, things have gone a bit “upside-down,” with a significant amount of effects work now being done live on set, requiring essential design planning to be completed during prep. This shift has much to do with the many productions leaning into virtual-production techniques, such as shooting in LED volumes and using real-time motion capture, which blur the line between on-set solutions and more traditional visual-effects workflows — which can further impact behind-the-scenes teamwork in unexpected ways.

In recognition of this fast-changing terrain and its significance for cinematographers, production designers and other members of the professional filmmaking pipeline, AC will be committing more editorial focus to the art of visual effects, exploring how new tools and techniques alter and advance the VFX paradigm for everyone on set.

Helping to spearhead this initiative is our new VFX editor, Joe Fordham, an alum of Cinefex magazine whose expertise in the effects arena will bolster our coverage with informed insights and analysis. Joe began his career in the U.K. making award-winning short films that were broadcast on BBC TV, Channel 4 TV, BAFTA/LA and Amazon. He has worked in film editing, animation, visual effects, special effects and creature effects in London and Los Angeles, and has also written articles for Cinefantastique and The Hollywood Reporter, as well as longer-form book projects for Titan Books.

The article by Joe that follows provides an overview of the current visual-effects landscape, with input from a group of top VFX professionals and cinematographers who have demonstrated their skill with effects integration. Our expanded coverage of the effects realm will include a new periodic column, The VFX Perspective, that will continue this magazine’s long and storied history of effects-oriented reportage.

“The industry has become dependent on VFX, from supernatural movies to movies [set in] Paris or New York [that] they shoot elsewhere. It’s an integral part of every movie.”

— Dariusz Wolski, ASC

Cinema itself is a visual effect, an illusion in which anything is possible. This principle has propelled the ingenuity of motion pictures since the era of Georges Méliès — and has progressed to the modern day, where productions can now capture an actor’s performance and use it to submerge a character, human or otherwise, into any world one may imagine. And it looks real.

There’s an inverse perspective as well — that “computer-crazy” visual effects are numbing audiences and placing a technological burden on productions to deliver more copious, and more sophisticated, VFX imagery for diminishing returns. This view is certainly contentious, but it underscores the complex creative tension that’s always existed between visual effects and cinematography — a give-and-take we’ll be exploring in this piece and in AC issues to come.

Prep and Testing

Some perceive visual-effects advances as an organic outgrowth of filmmaker relationships. Dariusz Wolski, ASC established his professional foothold in the heyday of MTV — shooting music videos for such directors as Alex Proyas and David Fincher — and then applied his creative approach to Proyas’ The Crow and Dark City, four Pirates of the Caribbean films and, so far, nine features with Ridley Scott, including Prometheus and The Martian. “The first directors I worked with came from visual-effects backgrounds,” Wolski says. “There was always a conversation about how best to incorporate effects. Very quickly you learn that the only way to make it great is with full collaboration, spending a lot of time together during prep, and testing. I was fortunate in that I worked with top-level visual effects people. On the Pirates films, visual-effects supervisor John Knoll was extremely supportive of the cinematography.

“The industry has become dependent on VFX, from supernatural movies to movies [set in] Paris or New York [that] they shoot elsewhere,” Wolski adds. “It’s an integral part of every movie.”

On Scott’s upcoming feature Napoleon, Wolski and Moving Picture Co. visual-effects supervisor Charley Henley devised a subtle trick to emulate period lighting. The cinematographer explains, “I shoot a lot of movies with real candles and rely on natural light and flames, but we were in places where there were 17th- and 18th-century paintings, so they were very careful about us not using real candles, especially in proximity of walls. We did a tremendous amount of tests; we made a little LED light in the candles and then replaced them with flames. That was very intricate.”

Defeating Limitations

On projects such as Titanic, Hugo and The Jungle Book, Robert Legato, ASC has helped shape once-cumbersome filmmaking technology into agile imaging tools. He began experimenting while shooting commercials for Robert Abel and Associates in the 1980s, using video playback to compose miniatures and motion-control elements. Decades later, while supervising visual effects for the first Harry Potter film, he employed a compositing system that the BBC developed with Radamec Broadcast Systems, using ceiling-mounted tracking markers to create lineups of live-action and miniature elements as a fleet of boats arrived at Hogwarts.

In the early 2000s, Legato employed camera-head-style pan-and-tilt wheels to control MotionBuilder previsualizations for Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator (shot by Robert Richardson, ASC), staging a biplane battle and Howard Hughes’ XF-11 plane crash. Legato proposed adapting the technology for Cameron’s Avatar: “Jim always wanted the ability to see a shot in the middle of doing a visual-effects scene. He graciously let me play on his nickel. We motion-captured a camera, taking live input from a motion-captured person as the avatar, and superimposed that over the viewfinder, and I could then take my live action and put it together.” The experiment laid the infrastructure for SimulCam architecture, which empowered Avatar’s Oscar-winning visual effects.

The evolution continued in Legato’s work with Bill Pope, navigating digital rainforests in The Jungle Book, and Caleb Deschanel, ASC, traveling through virtual savannas for The Lion King. For Legato’s latest collaboration with Richardson, director Antoine Fuqua’s Emancipation, he helped create an alligator attack on the lead character portrayed by Will Smith — a combination of a location stunt with animatronic and CG animation in an LED-backed water tank.

“As soon as you do any of this work,” says Legato, “you endeavor to find a way to defeat its limitations to create a more believable shot, a more fluid live action. There’s no separation between church and state; we are doing the same thing the cinematographer on the movie is doing, the same thing the director of the movie is doing, and we work with one another to create a seamless illusion that looks real. That is the heart of moviemaking. It’s all illusion.”

The cinematographer’s contribution to the color grade was a valuable resource on Denis Villeneuve’s Dune and the upcoming Dune: Part Two, for which Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS generated color bibles that shaped visual effects’ color pipeline for building composites based on desert locations. “Once the film finished shooting,” Fraser explains, “the assistant editor and I did an edit of the film in scene order. We knew that edit would change, so it didn’t follow a narrative arc whatsoever. I took wide shots and close-ups of important scenes, put those into a timeline, and graded them to capture Denis’ vision, and my vision. Desert/daytime: wide, close. Desert/dusk: wide, close. Ornithopter: wide, close. [It was] just a series of images that represented our intent. During the post process, as [visual-effects supervisor] Paul Lambert and his team added backgrounds, the color bible was a reference, so they could apply that LUT to make sure it was going the way we wanted.”

A Crucial Cross-Check

The ability for a production to retain a cinematographer’s services after shooting is often complicated by logistics. “I am fortunate,” says Wolski, “because in the movies I do with Ridley, we have the same colorist, Stephen Nakamura at Company 3. First of all, Ridley is a major policeman when it comes to visual effects. And then it’s Stephen who gets all the comps. Technically, you come in for a week, color your movie, and then there’s another month waiting for visual effects to trickle in. Economically, that is difficult because I am usually on another film [by then], and nobody is going to pay a DP to wait for shots to trickle in. But the system I have with Stephen and Ridley is a cross-check. There is a strong VFX producer, there is Stephen, there is Ridley, and everyone cross-checks. That’s instrumental in our movies.

“Technology is there to help us,” he adds, “but we have to know not to abuse it.”

Though modern visual effects have long offered opportunities to re-sculpt locations — as seen in The Martian and Prometheus — filmmakers must now also evaluate the facilities that video-game engines and LED-wall environments have opened as new horizons for creating exotic settings onstage.

Unreal Engine has recently developed more creative options for the virtual realm, and Fraser embraced them on The Mandalorian and The Batman. The ability to render 3D environments live, with camera tracking, interactive parallax, varieties of speeds, contrast and color adjustments, presents new artistic parameters — albeit based on familiar principles. “It’s no different than what we’ve always done in filmmaking,” Legato says. “You build a set, you paint it, you add props, and you figure out all of those details using your imagination to design what the shots are going to be. Building a set in the computer — it’s still a set. It has a time of day; it has atmospherics, or not; and you build all that before you step on the stage.

“Cinematographers must be part of the decision-making process to shoot on a volume. Cinematographers have to learn about technology, and we have to be a strong voice in the room when it comes to using technology.”

— Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS

“What I don’t like to do is to shoot generically, rely on postvis, and spend a lot of time double- and triple-guessing what to add later,” Legato continues. “VR is the opposite of that; it is more freeing. I like to make a decision because I can learn from that right away. If you forestall that, you end up with a ton of s--- thrown in at the last minute. To me, previs and VR get us closer to how you shoot for real, with live input. As a live-action filmmaker, I am more comfortable with that. Make up your mind. Am I going to shoot here or there? Is it afternoon or morning? All of that gets incorporated into your plan, and you live with it. That makes for the most memorable scenes.”

A Strong Voice in the Room

The Batman’s StageCraft environments took into account LED dynamic range, contrast ratios, strobing issues, atmospheric effects and the physicality of surrounding the set with a rigid wall that made acoustics resemble a racquetball court. “On the volume, we tried to mitigate sound issues,” notes Fraser. “We used all the acoustic options at our disposal — uneven walls, ceiling pieces that angled, baffles. There are reasons not to shoot in a volume, [and] that includes a commitment to shoot backgrounds 12 or more weeks out, as we did on Mandalorian. The idea that you can change out a bluescreen later I find a lot scarier.”

Virtual shooting, like any other filmmaking tool, works best when it is implemented with artistic purpose. “Cinematographers must be part of the decision-making process to shoot on a volume,” says Fraser. “Cinematographers have to learn about technology, and we have to be a strong voice in the room when it comes to using technology. We need to be involved along with the production designer and the VFX supervisor to decide if a tool is the right one for the job.”

Equally vital is comprehending how a choice on set may later impact post-production work. “For me, the use of witness cameras on set is potentially the most important issue with the camera crew,” notes VFX supervisor Lambert. “For instance, Greig, likes a small depth of field, and even if I covered an entire wall with tracking markers, I’m not going to be able to work out my virtual camera from that image. If I add a wide-angle prosumer witness cam on the side of the camera, I can track that, and I can spend more time being creative on a shot rather than spending all our budget trying to work out how to copy a camera move. We need to have those conversations. Some people are interested and some people don’t care, but trying to explain it can help my work, which is often a two-year commitment. We don’t want to hold anyone up on set. It’s important to collaborate so the crew knows what’s going on and we can quickly intercept any issues. That way, we can avoid getting called out by the 1st A.D.: ‘Ohhh, VFX is taking too much time!’”

Staging for Drama

The creative spark between camera and visual effects can be a dynamic tension between opposing forces. “Ridley pushes visual effects to the limit,” notes Wolski. “We know technology can do practically anything, except it is bombarded by budgetary restrictions. Visual effects will always fight for us to give them as friendly footage as possible, [and] that isn’t always necessarily aesthetically the best choice. Sometimes it’s better to shoot something more extreme and have them fight with it because that makes it real.”

Ultimately, visual effects are there to serve the film. “When you create a visual effect, it is composed, lit and staged for the drama that you are trying to capture,” Legato says. “If you don’t have an appreciation of that in visual effects, you are shorting the gifts you get from appropriate drama staging. The cinematographer does that every day, coalescing a scene into a shot where one composition leads to another. There’s art involved.”

Essential Conversations

Aligning a cinematographer’s aesthetic choices with visual-effects needs can be a high-wire act. Visual effects supervisor Paul Lambert has an appreciation for the dynamic between departments based on his background as a compositor. “It is essential to have a conversation with the director of photography or a director about what VFX can offer on set,” he says. “Having dealt with thousands of images in my career, adding backgrounds or removing details, I am acutely aware that when we add an element to an image, if it isn’t in the same space in the way it was lit, it will be a problem. We can push and pull the grade, but you can usually tell.”

Lambert’s experience includes innovating Nuke compositing software’s Image Based Keyer, which allows image extractions from unevenly lit backgrounds. “The visual-effects world is going leaps and bounds into being able to extract characters from normal backgrounds without bluescreens or greenscreens,” he says. “We have issues with hair, which is difficult to extract unless it’s up against a constant color. Otherwise, we’re at a point where we can add anything to a background. The intent must be correct. If the lighting in the foreground doesn’t marry what we intend to do with the background, it will look like a composite. My job is to get the best basis in the photography to then create what the director and the cinematographer intended.”

On Blade Runner 2049, visual-effects supervisor John Nelson invited Lambert to observe the photography of scenes under Nelson’s jurisdiction at DNeg. These included “Pink Joi,” wherein Agent K (Ryan Gosling) paused on a walkway to observe a neon-pink billboard of the holographic Joi (Ana de Armas). Lambert’s insights into Deakins’ bold lighting palette were then informed by LUTs that Deakins created in DI sessions with colorist Mitch Paulson at Company 3.

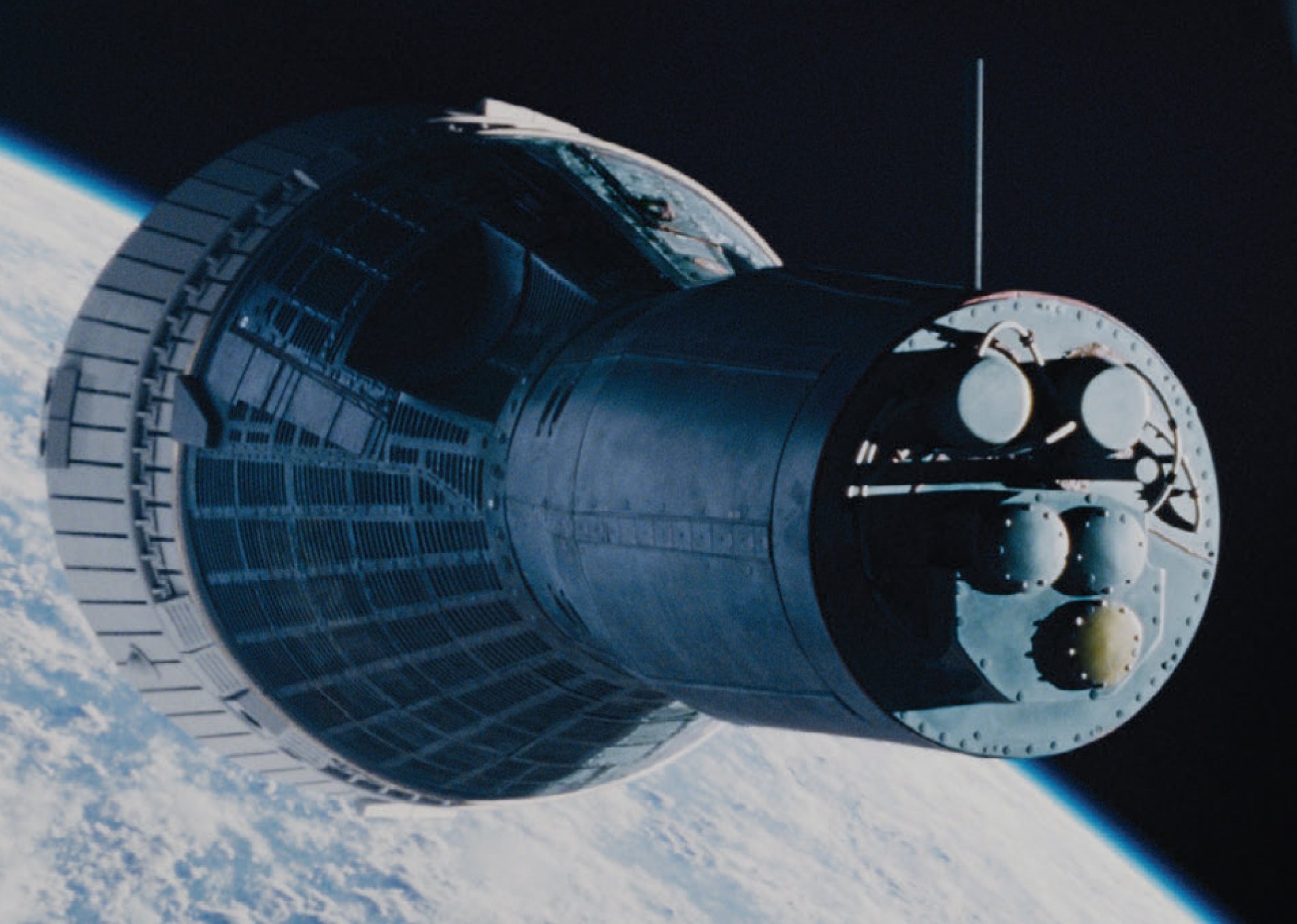

DNeg and Lambert were early practitioners of LED environments for Damien Chazelle’s First Man, shot by Linus Sandgren ASC, FSF. “This was before we could get the kind of interactivity you have with Unreal Engine,” Lambert explains. “We fed spherical QuickTimes into the playback system, which was perfect for scenes of vehicles flying through clouds and flying over the moon.”

LED lighting created natural highlights and reflections on spacesuit helmets in cockpits, while Sandgren used a mobile 10K on a truss to emulate sunlight flaring into the lens. “We did that old-school,” Lambert says. “We had playback on the screen that we could rotate and pull around. As we did that, they lined up the 10K to follow the sun. On the dailies, we’d see this 10K which we had to take out [digitally], but the motion of that light was the most important thing for me in visual effects. Light and movement. Everything else I can fix, but I can’t fix the lighting.”

— Joe Fordham

Reaching Into Writing

The VR format informed aesthetic choices on The Batman to a degree that might surprise many viewers.

Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS met Matt Reeves for lunch while Reeves was writing his superhero film. They had been friends since they collaborated on the vampire drama Let Me In.

While remaining tight-lipped about details, Fraser noted some lessons he had learned with ILM using LED backgrounds on Star Wars: Rogue One, and StageCraft tools for Season One of The Mandalorian. “I mentioned to Matt what looks good or bad in the volume,” Fraser recalls. “He’s a smart guy, and he quizzed me. In the next draft of his Batman script, Batman and Gordon met on an unfinished skyscraper. There were lots of steel girders. The scenes took place at dusk, dawn or night, with a lot of talking. Everything I’d told Matt the volume was good for — controlled lighting, long scenes, simple geometric structures — he wrote to that. That’s how it should be. When writers and producers have a better understanding of what works in a volume, they can lean into it as they write.”

— J.F.

A Virtual-Production Debut

Magdalena Górka ASC, PSC encountered her first LED-volume-based shoot on the Paramount Plus series Star Trek: Strange New Worlds.

The LED volume, created and operated by Pixomondo in Toronto, was used to create realistic, immersive virtual environments. “The LED walls were a game-changer for us,” Górka says. “We created stunning visual backdrops that added depth and dimension to the scenes. The level of detail and realism we achieved was remarkable.”

She also enjoyed having the flexibility to add or modify some details in real-time. “You could add simple elements to the backgrounds on the production day. Transparent elements could also be added easily with a few hours of programming and rendering.”

Limitations of the process that she noted included lag in camera tracking, a critical aspect of in-camera VFX. She explains, “Most of the time, [the problem] was fast movements, because the rendering engine could not keep up. We couldn’t do fast Steadicam moves or 180-degree pans with actors running, for example, as the tracking cameras couldn’t process it at that speed. However, I believe this limitation will be overcome as the technology advances.”

Regarding color grading, Górka emphasizes the advantages of shooting with LED walls compared to traditional greenscreens, noting, “We don’t have green spill to deal with on set or in post.”

— Noah Kadner