Totally ’80s

In tribute to American Cinematographer’s 100th anniversary, we look at the magazine’s memorable coverage in this decade of innovation, experimentation and excess.

Reflecting a rather dour decade — marked by endless conflict in Vietnam, civil unrest, Watergate and the fall of Nixon, and a general fraying of the social fabric — the movies of the 1970s became overwhelmingly heavy, man. Antiestablishmentarianism, nihilistic characters, and provocative tales of paranoia were increasingly normalized, even in the far-more-wholesome realm of network television.

Yet the astonishing box-office success of such optimistic, hero-driven, mid-to-late-’70s films as Jaws, Rocky, Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Superman: The Movie, and even Grease pointed in a new direction, with the studios seeking to capitalize on a perceived resurgence in “crowd-pleaser” pictures. Executives soon began green-lighting more high-dollar projects featuring dynamic cinematography and the latest in rapidly evolving visual-effects techniques.

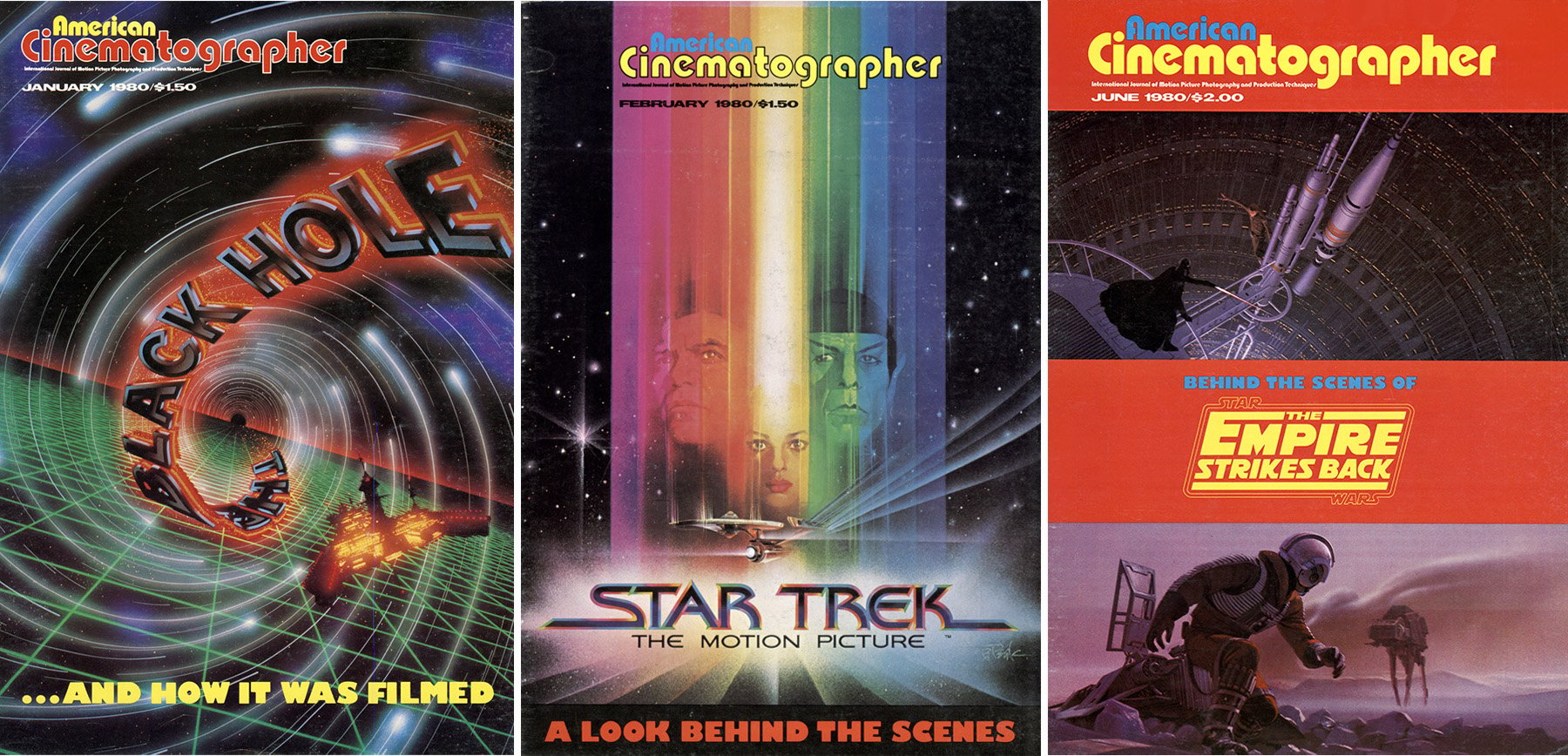

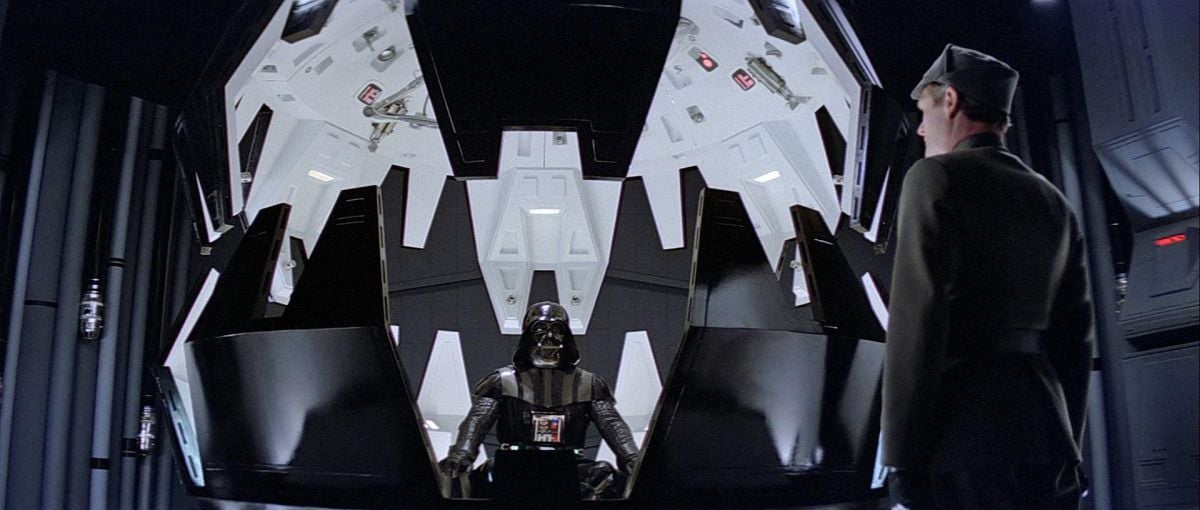

During the 1980s, American Cinematographer documented many of the resulting projects, launching into this new decade with a series of in-depth cover stories on such ambitious genre efforts as The Black Hole (AC Jan. ’80; shot by Frank Phillips, ASC), Star Trek: The Motion Picture (AC Feb. ’80; Richard H. Kline, ASC) and Star Wars: Episode V — The Empire Strikes Back (AC June ’80; Peter Suschitzky, ASC).

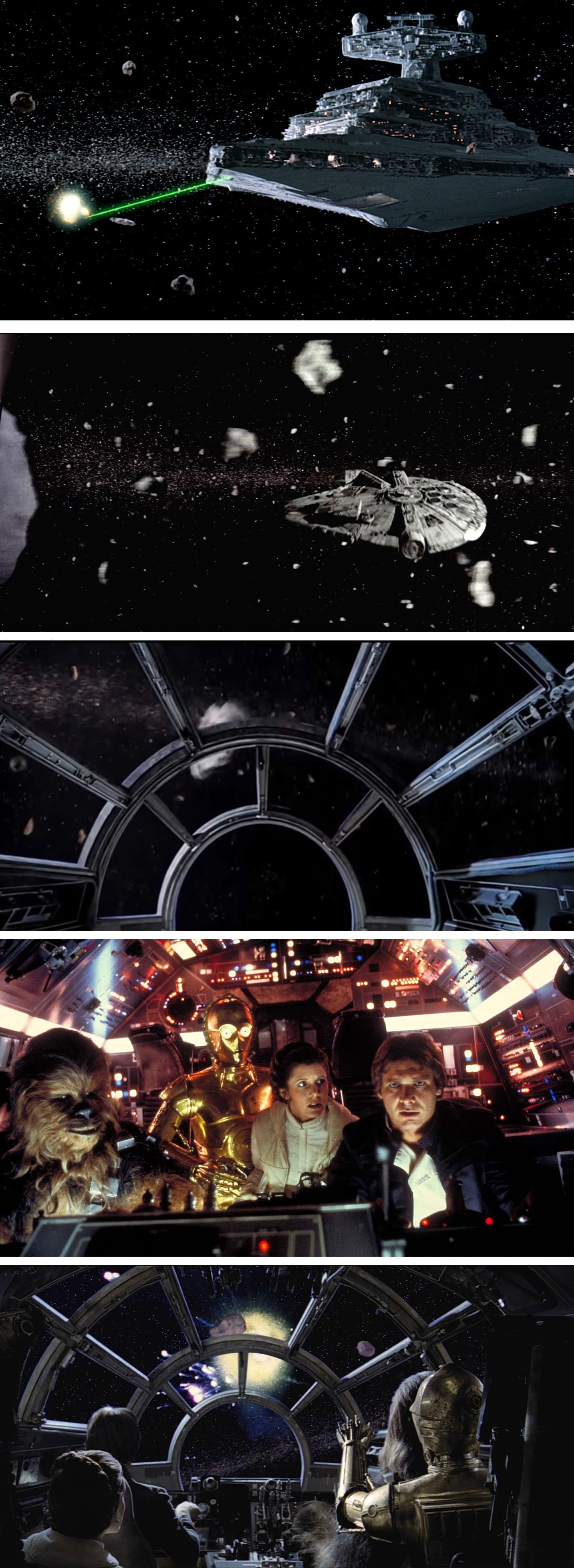

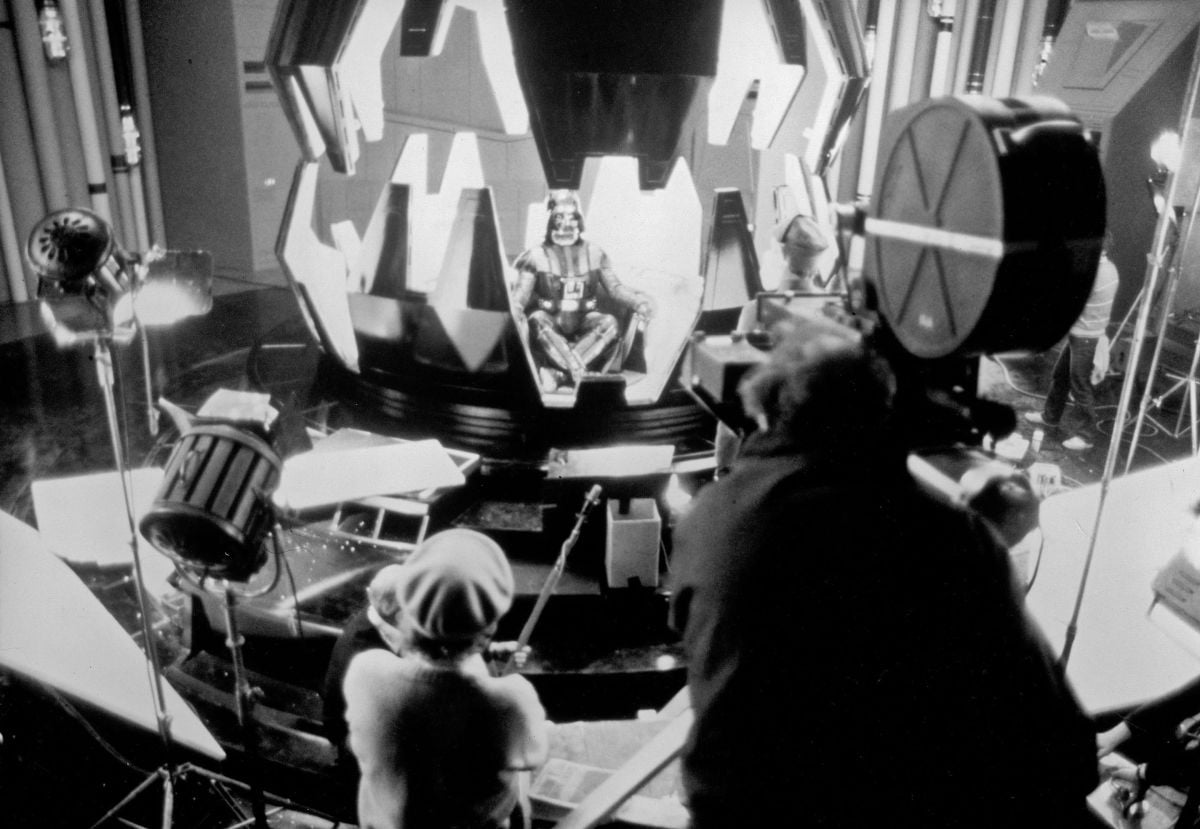

The June 1980 issue featuring Empire boasted total coverage on the complex production, with no less than nine major feature stories — detailing principal photography, visual effects (in a piece penned by Richard Edlund, ASC), optical photography, effects photography (featuring Dennis Muren, ASC), matte-painting work, and even the project’s extensive aerial filming. (Similarly lavish spreads would be bestowed upon Empire’s followup, Return of the Jedi, in June ’83.)

While Suschitzky was challenged by Empire’s effects needs and often difficult sets (especially the swampland abode of diminutive Jedi master Yoda), he enthused, “I haven’t enjoyed myself so much on a film for a very long time. I worked with a director [Irvin Kershner] with whom I really got along tremendously, who encouraged me to do my utmost, and so I had a ball on it, really, and lots of large toys to play with. What more could one want?”

This cover-to-cover expanded reportage would become a hallmark of AC through the rest of the ’80s, as the magazine had the trust of the studios and the respect of filmmakers who grew up reading it — and wanted nothing more than to have their projects featured in its pages.

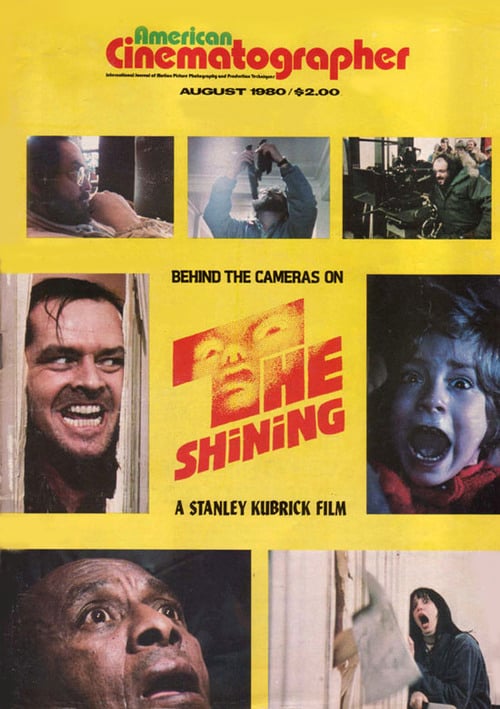

While the August 1980 cover story on The Shining went in-depth with cinematographer John Alcott, BSC discussing director Stanley Kubrick’s limitless attention to detail, it was the companion piece penned by Steadicam inventor and operator (and future ASC associate member) Garrett Brown that really wowed readers. The film perfectly showcased how his camera stabilizer could be creatively integrated into a production to design a unique visual approach that was appropriate to the story — rather than simply being employed for trick shots. Brown’s account succinctly explained his fruitful collaboration with Kubrick and Alcott.

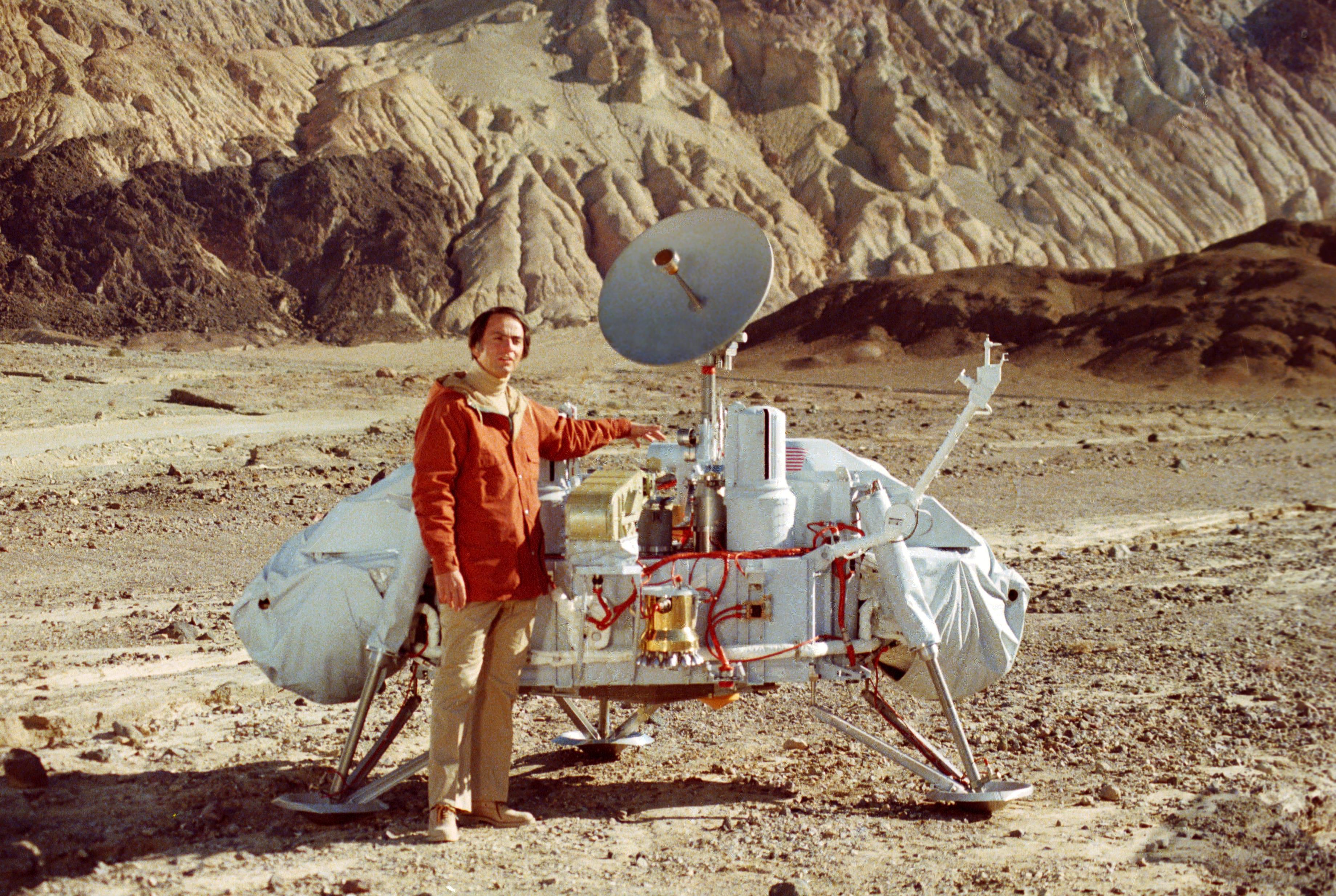

Though television has been a key part of AC’s reporting since the medium’s inception in the 1930s, extensive cover stories in the 1980s on such landmark programs as the 12-hour period epic Shogun (AC Sept. ’80; shot by Andrew Laszlo, ASC), the 8-hour drama East of Eden (AC Feb. ’81; Frank Stanley, ASC), the influential 13-part science series Cosmos (AC Oct. ’80; H.J. Brown and Chris O’Dell) and the 18-hour World War II epic The Winds of War (AC Feb. ’83; Charles Correll, ASC) were novel.

Meanwhile, documentation of TV’s nascent transition toward more realistic, cinematic lighting began in AC via an in-depth interview with William H. Cronjager, ASC, who won an Emmy for the gritty camerawork he lent to the pilot of the groundbreaking cop series Hill Street Blues (AC March ’81).

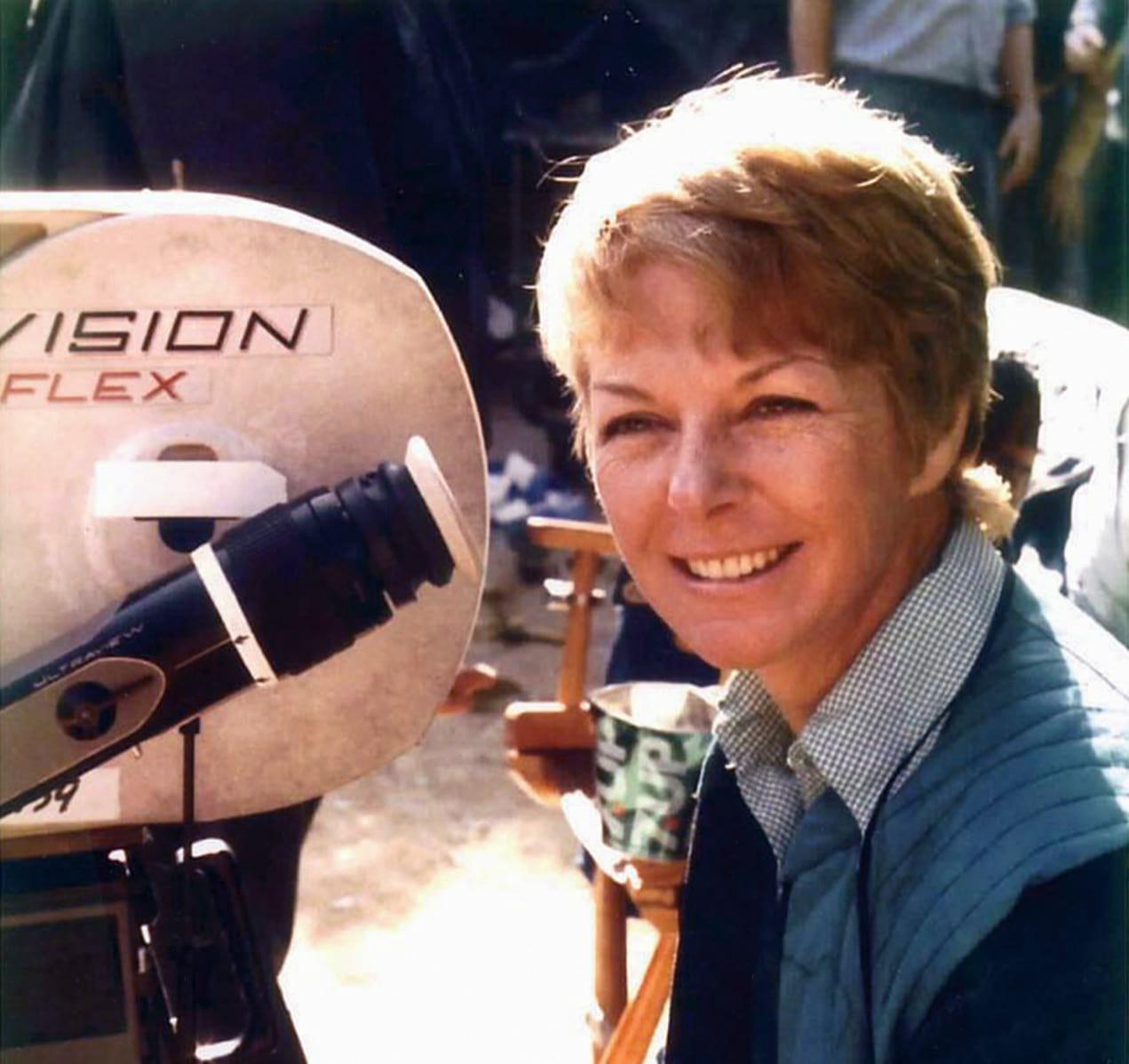

Another TV cover story of note, in the April ’86 issue, showcased the work of cinematographer Brianne Murphy, ASC on the network series Highway to Heaven. She was not only the first woman cinematographer to be featured on the cover of AC, but the first to be invited to join the Society, in 1980, and to serve on its Board of Governors.

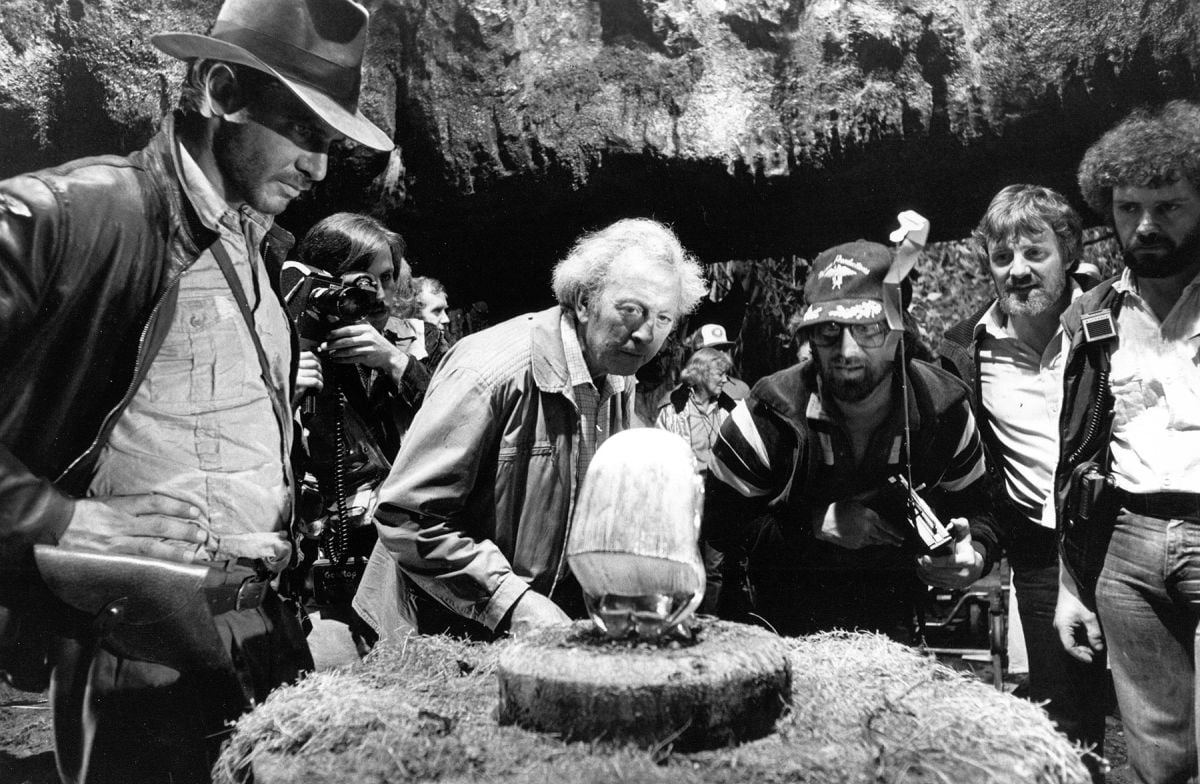

First-person stories often provided readers with a sense of immediacy — bringing them closer to the artists they admired. These articles included Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, HSC’s piece on shooting the epic Western Heaven’s Gate (AC Nov. ’80); Sven Nykvist, ASC discussing his 1930s drama Cannery Row (AC April ’81); Steven Spielberg, Douglas Slocombe, BSC and Edlund explaining their contributions and collaborations throughout the production of Raiders of the Lost Ark (AC Nov. ’81); Jost Vacano, ASC, BVK describing his tour of duty on Das Boot (AC Dec. ’82); and cinematographer Thomas Mauch chronicling the production of Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (AC Aug. ’83). Each piece offers a unique voice, with the filmmakers speaking for themselves.

Notably, Spielberg would become a frequent figure in the pages of AC throughout the 1980s, next with a cover story on the making of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (AC Jan. ’83). The reporting detailed not only the production, but the compelling story of self-taught cinematographer Allen Daviau, whose longtime friend brought him aboard to photograph this personal story of an awkward 10-year-old who forges an unusual friendship — resulting in the cinematographer’s sudden meteoric rise from obscurity to Oscar-nominated exceptionalism and, later, ASC membership. Daviau would also become a mainstay in AC coverage; he and Spielberg were subsequently featured in a February ’86 cover story on The Color Purple, and again in January ’88 for Empire of the Sun.

Following Hollywood’s major changing of the guard in the 1960s and ’70s — with bold new voices given the opportunity to make uncompromising films — the 1980s continued that sense of experimentation. Look, for example, to AC’s coverage on the psychedelics-fueled sci-fi drama Altered States (AC March ’81), which featured not only cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth, ASC detailing his collaboration with director Ken Russell, but a lengthy historical piece on research into altered psychological states, including those induced by LSD, mescaline and hallucinogenic mushrooms — the latter also known as “God’s flesh.”

Full coverage on the phantasmagorical and equally trippy music film Pink Floyd: The Wall — which teamed director Alan Parker with cinematographer Peter Biziou, BSC — provided a sobering view of the hard work it takes to imagine and execute unusual, and often disturbing, images.

AC meticulously reported on the unconventional and opulent production of the fantasy epic Dune (AC Dec. ’84), directed by David Lynch with cinematographer Freddie Francis, BSC behind the camera. The surreal, dreamlike picture was a creative triumph, but often confounding, and it did not connect at the box office. Fortunately for cineastes, Lynch rebounded with the brilliant and harrowing neo-noir Blue Velvet, shot by Frederick Elmes, ASC. (AC Nov. ’87).

Cronenweth was again showcased, this time in AC’s July 1982 issue, with a cover story on Blade Runner. His cinematography on the sci-fi classic is now considered one of the best examples of the craft, and helped make this issue of AC perhaps the decade’s most popular — even now, nearly 40 years later. It’s perhaps surprising, though fitting, that a key inspiration for Cronenweth and director Ridley Scott on this futuristic thriller was Gregg Toland, ASC’s work on Citizen Kane (1941), which was also well ahead of its time when released and also only later fully appreciated. High contrast, unusual camera angles, and shafts of light were key visual goals for Blade Runner — “a piece that calls for extremes,” Cronenweth said.

That same 1982 issue was also the first under the reins of a new editor-in-chief, Richard Patterson, who had collaborated with and then replaced longtime editor Herb A. Lightman, who had served in the position since 1966. Also coming aboard was associate editor and historicals expert George E. Turner, who expanded AC’s retrospective coverage of classic films, and also its focus on visual-effects work. Turner would become editor of the publication in 1985.

The 1981 launch and immediate popularity of MTV soon began to have an impact on theatrical films. Combining punchy pop music with post-classical editing — characterized by shorter shot lengths and more jump cuts and close-ups — resulted in extended montages largely designed to evoke emotion and mood rather than a strict narrative progression. Vivid examples are seen in such stylish films as Liquid Sky (AC Feb. ’84; shot by Yuri Neyman, ASC), Flashdance (AC April ’84; Don Peterman, ASC), Desperately Seeking Susan (AC July ’85; Edward Lachman, ASC), 91⁄2 Weeks (AC Aug. ’85; Peter Biziou, BSC), To Live and Die in L.A. (AC Aug. ’85; Robby Müller, BVK, NSC) and Top Gun (AC May ’86; Jeffrey L. Kimball, ASC).

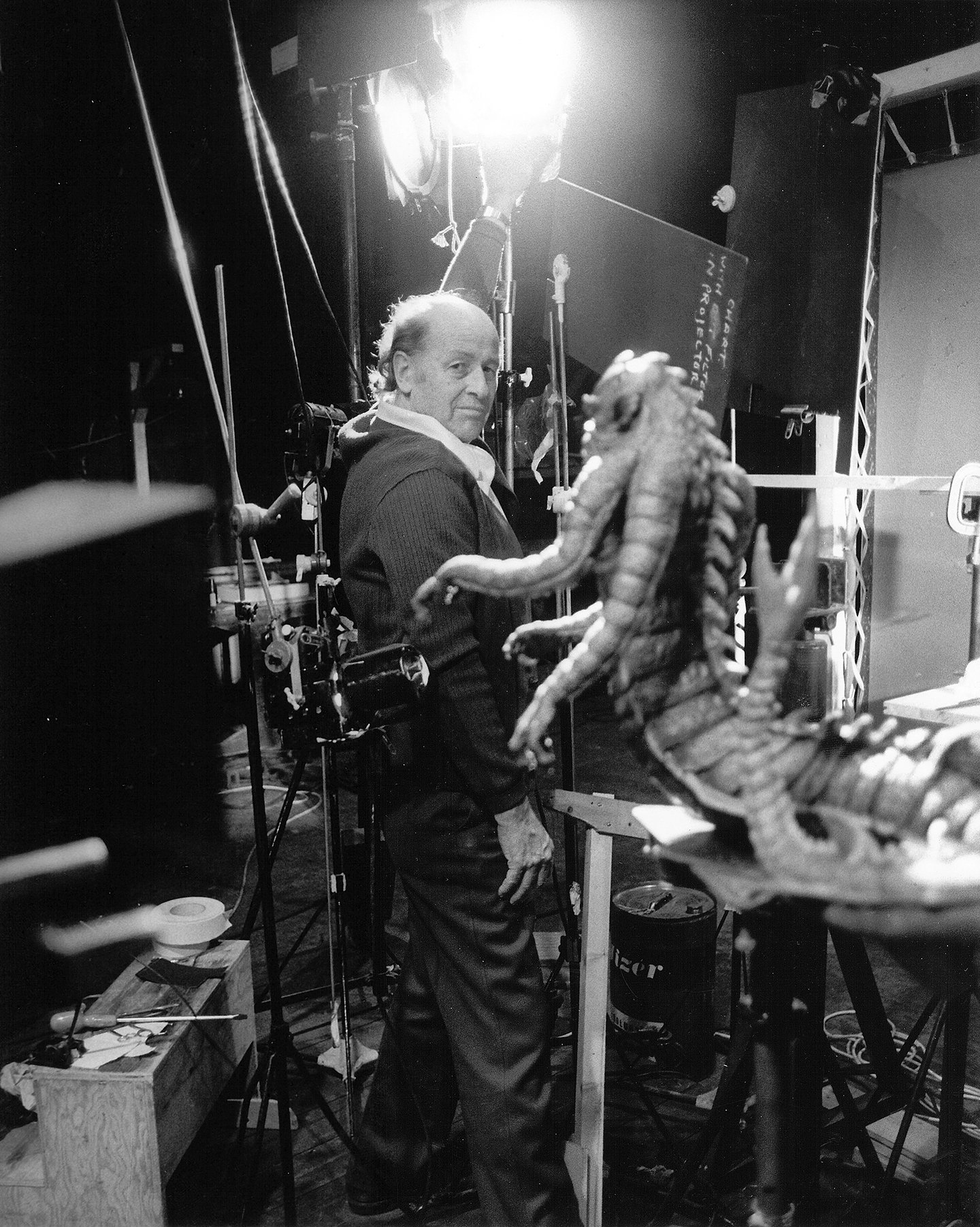

Coverage of visual effects expanded throughout the decade as an increasing number of productions employed this specialized artistry, with AC’s December issues dedicated to covering the latest and greatest VFX projects. Of course, the tried-and-true trickery of stop-motion animation master Ray Harryhausen — who employed improved-upon techniques he’d originally learned from his mentor, Willis H. O’Brien, in the 1940s — still produced dazzling work, resulting in a cover story on Harryhausen’s creature-filled epic Clash of the Titans (AC June ’81).

The movie would be his final feature effort, as his old-school “dynamation” technique was overtaken by computer-assisted screen magic. (Though it was no accident that Phil Tippett’s exceptional CBS television stop-motion project Dinosaur! would be featured in the April ’86 issue, as AC has long been fascinated with this arcane filmmaking technique.)

While highlighting the increasing use of visual effects, the advances in “electronic cinema” were also touted (some perhaps prematurely). These included the prospects of rapid video editing; image compositing; high-resolution digitizers capable of entering complex geometric shapes for image manipulation; computerized color control; NHK’s introduction of 1,125-line high-definition television in Japan; experiments in transferring HD images to 35mm film; and the first video cameras marketed as Hollywood-production-ready, such as the Ikegami EC-35 and Panavision’s Panacam Reflex.

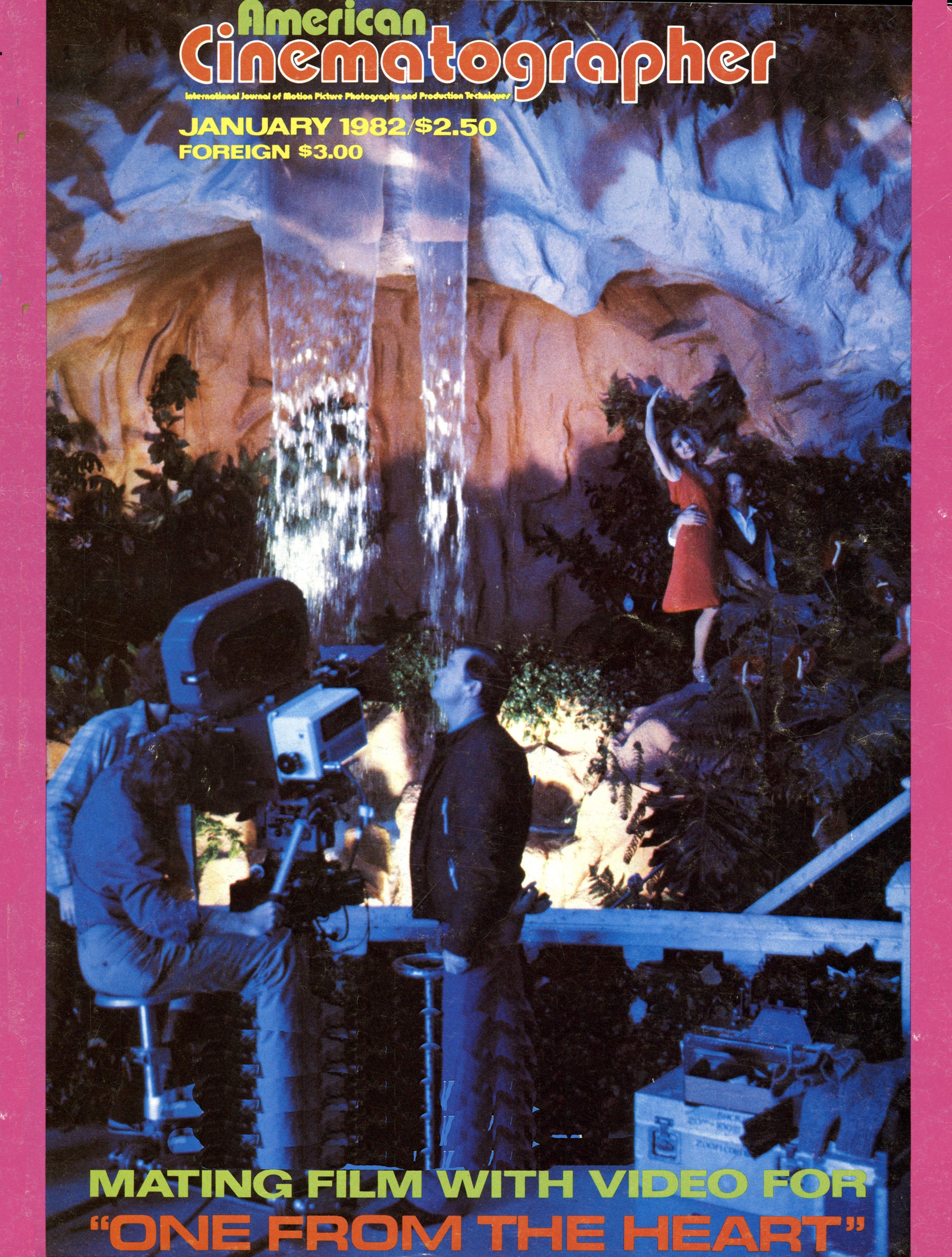

As covered in AC’s January 1982 issue, Francis Ford Coppola’s One From the Heart provided an early example of how emerging technologies would begin to reshape a filmmaking process that was already more than 80 years old and largely unchanged since the late 1920s. During prep, “Francis spoke of his desire to electronically link each department with our nine sound stages and have the ability to pump images, sound and data around like ‘hot and cold water,’” wrote Thomas Brown, an executive at Coppola’s Zoetrope Studios. This would be accomplished with the help of a “stage electronics package” (consisting of Betamax recorders to capture video feeds, as well as monitors and an intercom system) and the “Image and Sound Control Vehicle” (aka the “Silverfish,” a converted Airstream trailer outfitted as a mobile-editing, remote-viewing, previs and direction station).

Director of photography Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC rapidly adapted to a new production methodology, which included his pre-shooting rehearsals with a small video camera. This black-and-white footage could be cut immediately and woven into an already extensively assembled previs package.

During the shoot, Coppola largely directed from within his high-tech trailer, observing the action on screens, whose image was captured via a video-tap rig aboard Storaro’s Technovision camera. Both he and Storaro had the ability to view replays, which could, among other benefits, help determine whether to print a given take. The printed 35mm takes were transferred to video with time code, and then cut to match the previs.

This may sound much like standard practice on some productions today, but in the early ’80s, what Coppola described as “filmmaking’s greatest leap forward since the advent of sound in 1927” was tantamount to witchcraft, and not quickly adopted. But the magazine followed up with plenty more coverage on “electronic cinema” — noting in a subsequent editorial, “American Cinematographer is concerned with any technique or process which furthers the art of moving images. While we have no intention of sounding the death knell for film, we do recognize that the time has come to embrace fully the electronic image and all the techniques for recording and processing it. In fact, we recognize that we have some catching up to do.”

A few years later, a notable story featured the video-to-film process employed on the improvisational indie feature Heat and Sunlight (AC Nov. ’87; shot by Tomas Tucker), a production that managed to make the leap to big-screen theatrical distribution. But the “film vs. tape” debate persisted in AC’s pages for almost three decades, finally subsiding only when digital capture replaced HD video in the 2000s.

Advances in computer graphics during the 1980s allowed for their first major creative use in feature films, with AC documenting their groundbreaking — though still limited — employment on such movies as Tron (AC Aug. 1982; shot by Bruce Logan, ASC), Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (AC Oct. ’82; Gayne Rescher, ASC), The Last Starfighter (AC Nov. ’84; King Baggot, ASC) and Young Sherlock Holmes (AC Mar. ’86; Stephen Goldblatt, ASC, BSC).

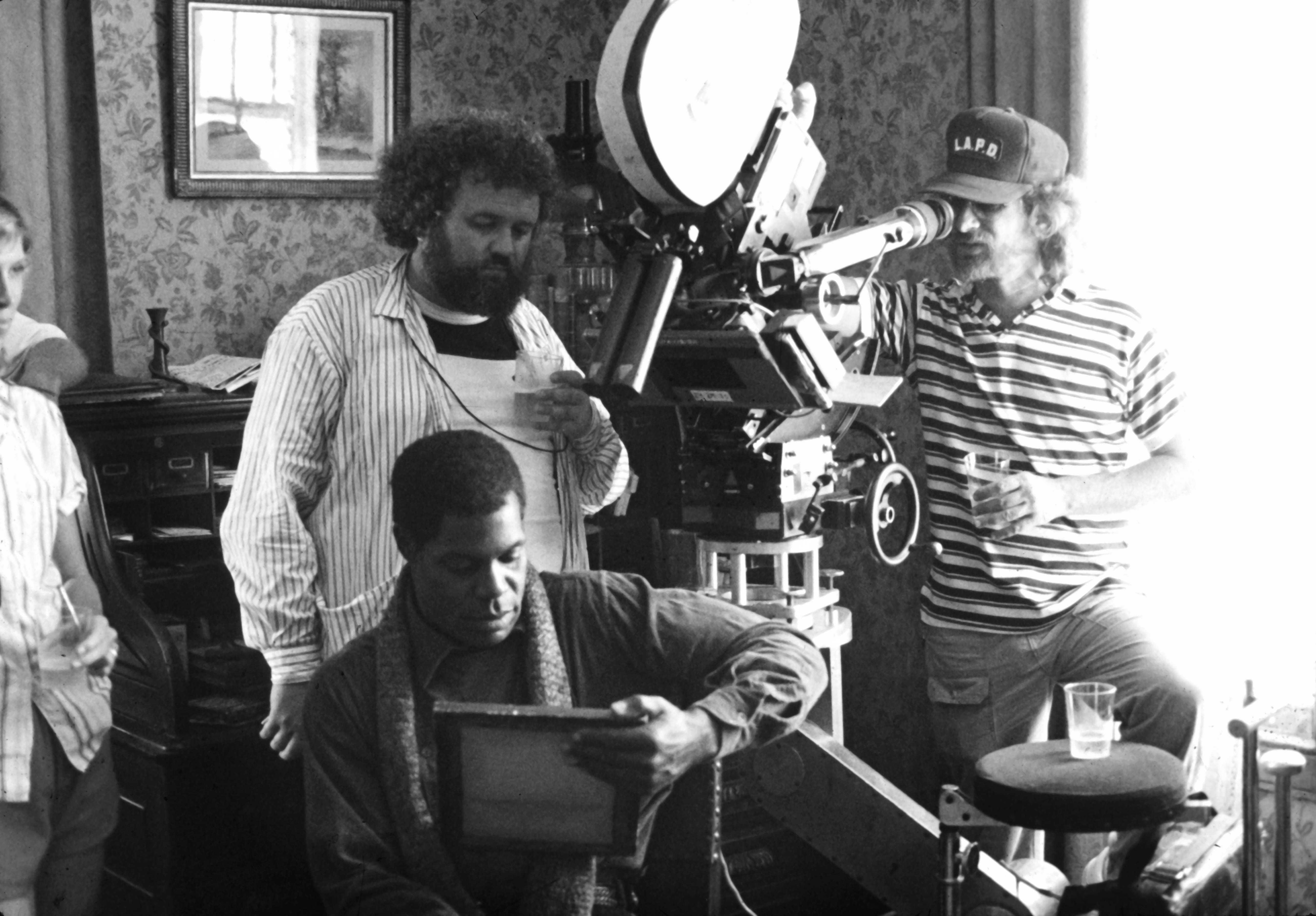

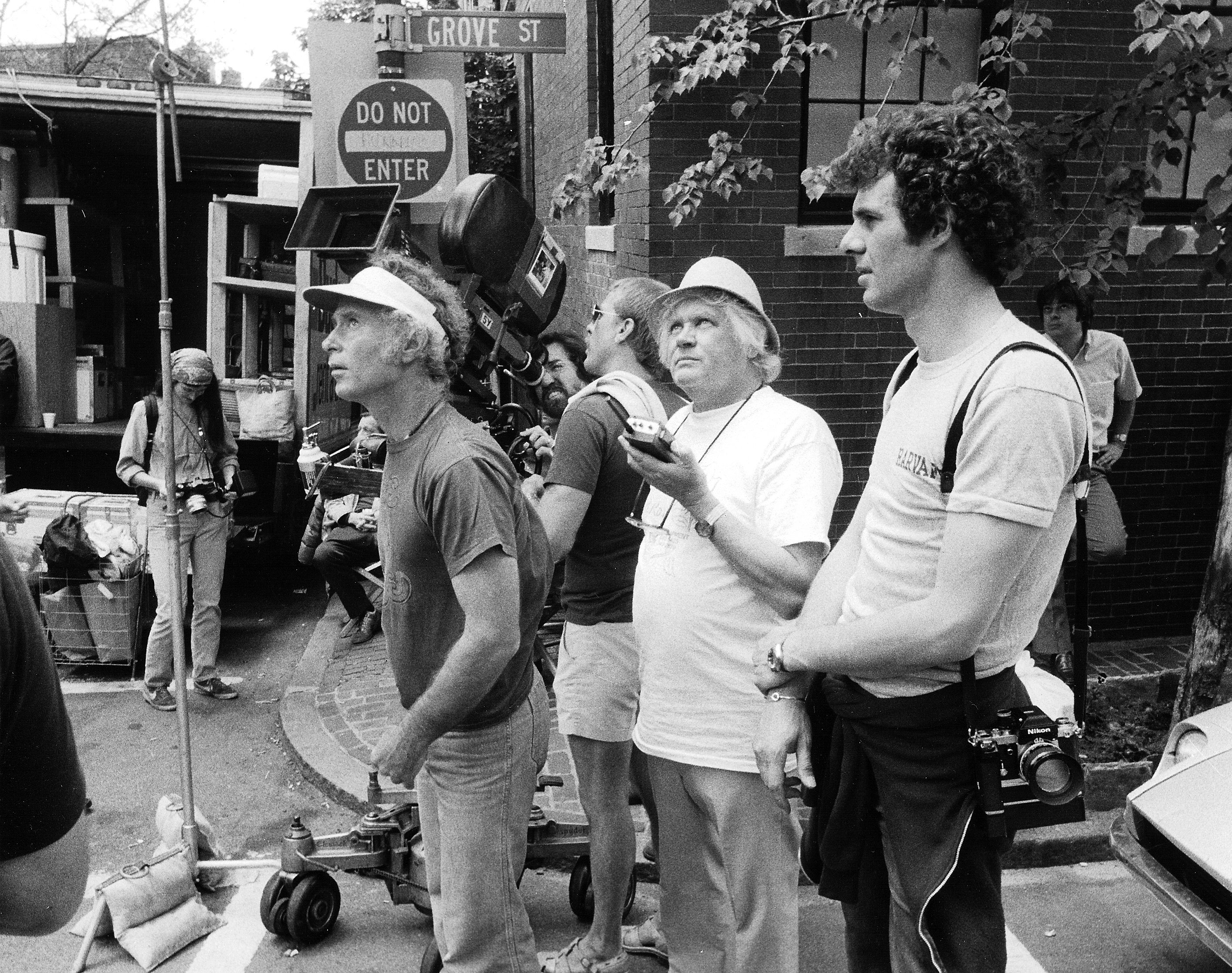

Throughout the ’80s, unique projects and new talents were featured in AC’s pages, and many became iconic. These films and cinematographers included Gremlins (Nov. ’84; shot by John Hora, ASC), Paris, Texas (Feb. ’85; Robby Müller, BVK, NSC), The Terminator (April ’85; Adam Greenberg, ASC) The Natural (April ’85; Caleb Deschanel, ASC), Lethal Weapon (April ’87; Stephen Goldblatt, ASC, BSC), The Untouchables (July ’87; Stephen H. Burum, ASC), Predator (Aug. ’87; Don McAlpine, ASC, ACS), Full Metal Jacket (Sept. ’87, Douglas Milsome, ASC, BSC), Wall Street (Dec. ’87; Robert Richardson, ASC), School Daze (Feb. ’88; Ernest Dickerson, ASC), Beetlejuice (April ’88; Tom Ackerman, ASC), Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (July ’88; Dean Cundey, ASC), Coming to America (Aug. ’88; Woody Omens, ASC), Dead Poets Society (Sept. ’89; John Seale, ASC, ACS) and Honey, I Shrunk the Kids (Dec. ’89; Hiro Narita, ASC).

There’s no doubt that the 1980s provided new opportunities for those willing to accept and integrate new technologies and methods into their creative process — but the decade also ended with the passing of many ASC greats, including L.B. Abbott, Lucien Ballard, Daniel L. Fapp, George Folsey, Milton Krasner, Ernest Laszlo, Joe LaShelle, Harold Rosson, Robert L. Surtees and Joe Walker.

Change is one element of filmmaking that never stops, and the pace would become even faster in the 1990s.

For access to 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, including every issue noted in this story, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.