Modern Times: AC Since 2010

American Cinematographer has spent the past decade documenting outstanding camerawork that continues to raise the creative bar.

Every year, new and daring motion pictures capture the zeitgeist, change the discussion, and plot a fresh course for the industry to follow. They do it by presenting story and characters in a unique light or novel way. This happened with such milestone features as Intolerance, King Kong, Gone With the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, Citizen Kane, The Robe, Lawrence of Arabia, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Wars, Apocalypse Now, Blade Runner, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, The Last Emperor, JFK, Schindler’s List, Seven, Saving Private Ryan, The Matrix and 300.

The visual power of these films — among others — sparked conversation among not only filmmaking professionals but also general audiences; many were deeply affected by what they had seen, their eyes perhaps opened to how artfully crafted images can elevate a story into a meaningful emotional experience.

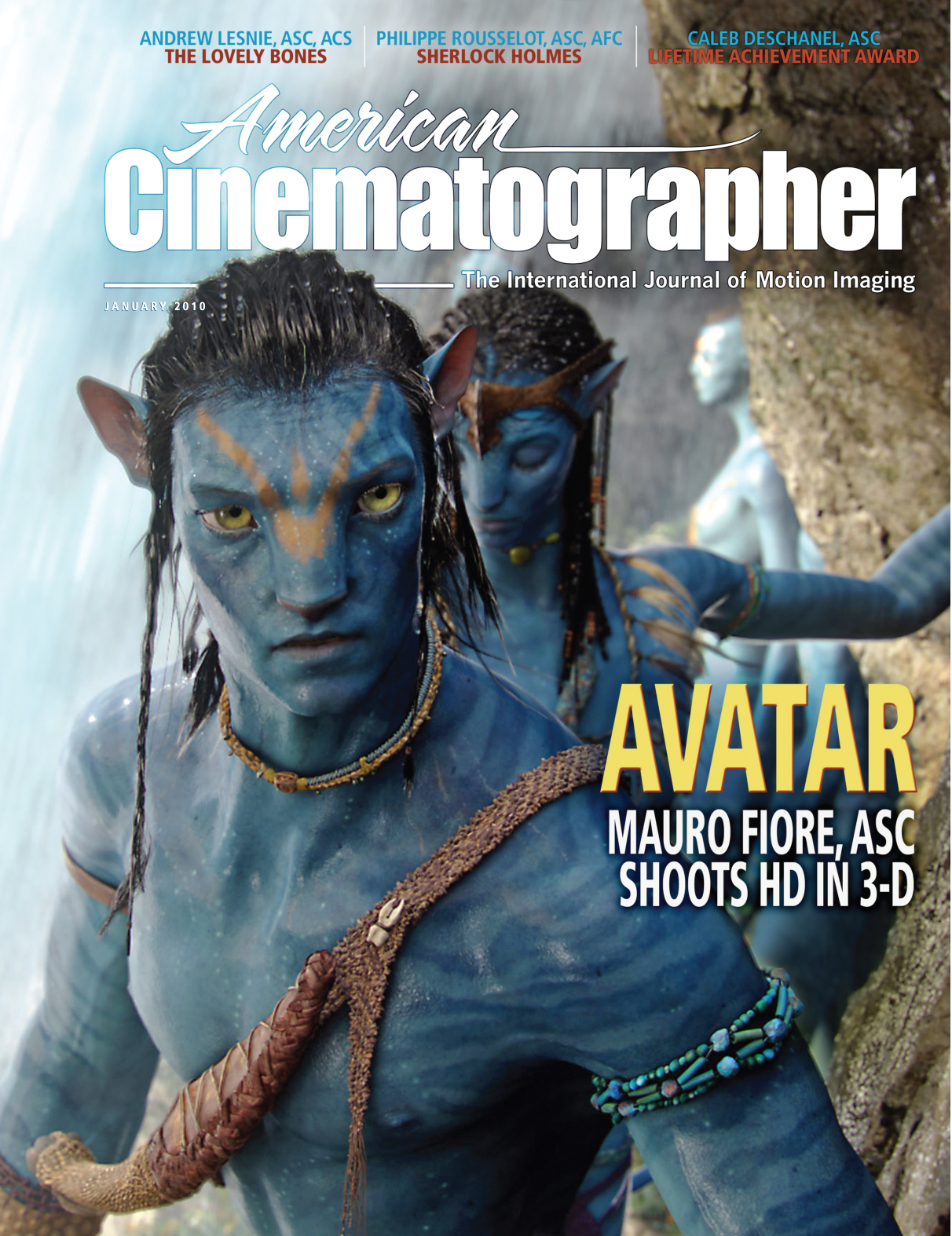

As the January 2010 issue of American Cinematographer landed around the world, the cover story on James Cameron’s 3D sci-fi spectacular Avatar (released in late 2009) perfectly reflected this kind of transformative phenomenon. Lavishly produced, with every technological and creative advantage in play, the picture offered a fantastic story of resistance and romance, grounded in part by a sense of reality conveyed in the cinematography of Mauro Fiore, ASC. Every composition was dynamic, the colors vibrant, and the “bio-luminescent” lighting atmospheric, but the alien world of Pandora remained relatable and worthy of exploration. It became a destination audiences returned to again and again, much as they had for Cameron’s Titanic (Dec. ’97).

Avatar offered an immersive experience in part because of the cutting-edge 3D digital Fusion Camera rigs designed and built by Cameron and Vince Pace, ASC; these could acutely control the complex interocular and convergence dynamics with which stereoscopic-imaging systems simulate the perception of depth. “It required a lot of experimentation and a reinterpretation of how I deal with composition and lighting,” Fiore told AC. “There were times when it was a miserable experience, but if you’re going to delve into new technology and a new world, Jim Cameron is the guy to do it with.”

Three months later, Fiore won the Academy Award and received an ASC Award nomination for his work on the picture, and by then Avatar had already become a new benchmark for epic storytelling. Its financial success also helped demonstrate that 3D was a viable tool when applied to the right story, and the format subsequently enjoyed a revival, used in such films as Tron: Legacy (Jan. ’11), Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides (June ’11), Hugo (Dec. ’11), Oz the Great and Powerful (April ’13), The Martian (Nov. ’15), Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk (Dec. ’16) and Gemini Man (Nov. ’19).

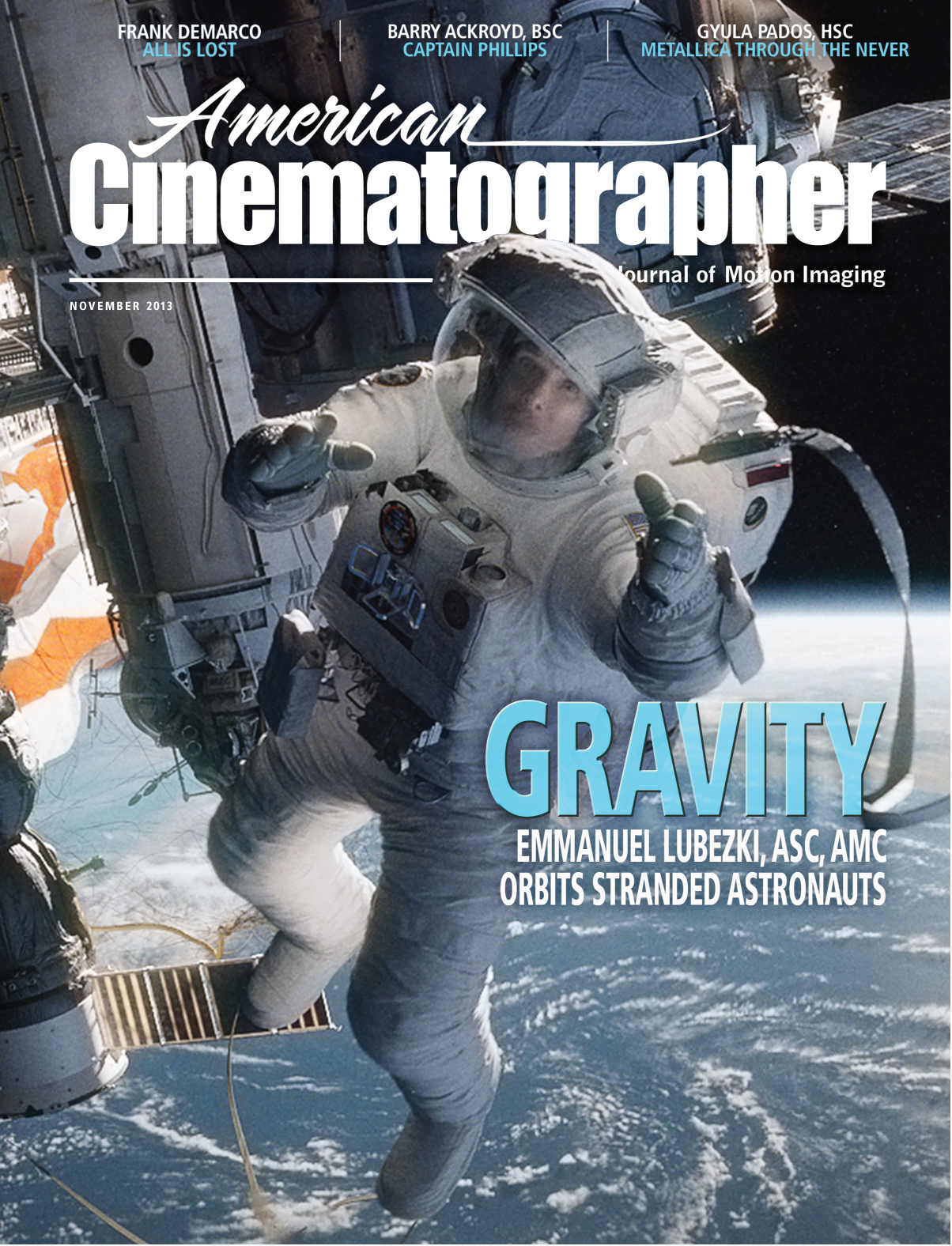

The gripping outer-space adventure Gravity (Nov. ’13), directed by Alfonso Cuarón and photographed by longtime collaborator Emmanuel Lubezki, ASC, AMC, delivered another technical tour de force. Replete with hyperreal visual effects supervised by Tim Webber, the movie’s astonishing imagery accentuated the sense of cinema with seemingly impossible shots. The approach meshed perfectly with the plot, featuring a lone astronaut struggling to survive a catastrophic low-orbit disaster.

Continuing the serpentine shooting style they had established on previous pictures, Cuarón and Lubezki strove to “involve the viewer with long takes and the elasticity of the shot,” the cinematographer told AC. “We wanted to keep a lot of our shots elastic — for example, to have a shot start very wide then become very close, and then go back to a very wide shot.”

Lubezki believes the long take (plano sequencia in Spanish) brings the audience into the movie in a striking way. “The plano sequencia is immersive. To me, it feels more real, more intimate and more immediate. The fewer the cuts, the more you are with [the characters]; it’s as if you’re feeling what they’re going through in real time. This is something Alfonso and I discovered on Y Tu Mamá También and Children of Men.”

Webber, who led the visual-effects team at Framestore in London, convinced Cuarón that his desire for long takes with a “zero-gravity” camera required that they go virtual, with the actors’ faces often the only practical element in a CG realm. “We needed the freedom of a virtual camera,” says Webber, “so we created a virtual world and then worked out how to get human performances into that world.” As a result, Lubezki’s role as the director of photography expanded far beyond the live-action realm. “The biggest conundrum in trying to integrate live action with animation has always been the lighting,” he noted. “The actors are often lit differently than the animation, and if the lighting is not right, the composite doesn’t work. It can look eerie and take you to a place animators call ‘the uncanny valley,’ that place where everything is very close to real, but your subconscious knows something is wrong. That takes you out of the movie. The only way to avoid the uncanny valley was to use a naturalistic light on the faces and to find a way to match the light between the faces and surroundings as closely as possible.”

Lubezki’s onscreen legerdemain helped turn Gravity into a box-office smash that won seven Academy Awards — including Oscars for Cuarón, Lubezki and Webber — and elevated audience expectations. The decade’s subsequent action-packed titles — among them Godzilla (June ’14), Edge of Tomorrow (July ’14), Mad Max: Fury Road (June ’15), Ghost in the Shell (May ’17) and Mission: Impossible – Fallout (Sept. ’18) — all strove to deliver similar dynamic urgency and visual virtuosity. Another of the most anticipated action films of this decade, the James Bond adventure No Time to Die, remains unreleased at this time, delayed by the Covid-19 pandemic that has disrupted so many other productions and release plans, but AC provided comprehensive coverage in our April 2020 issue.

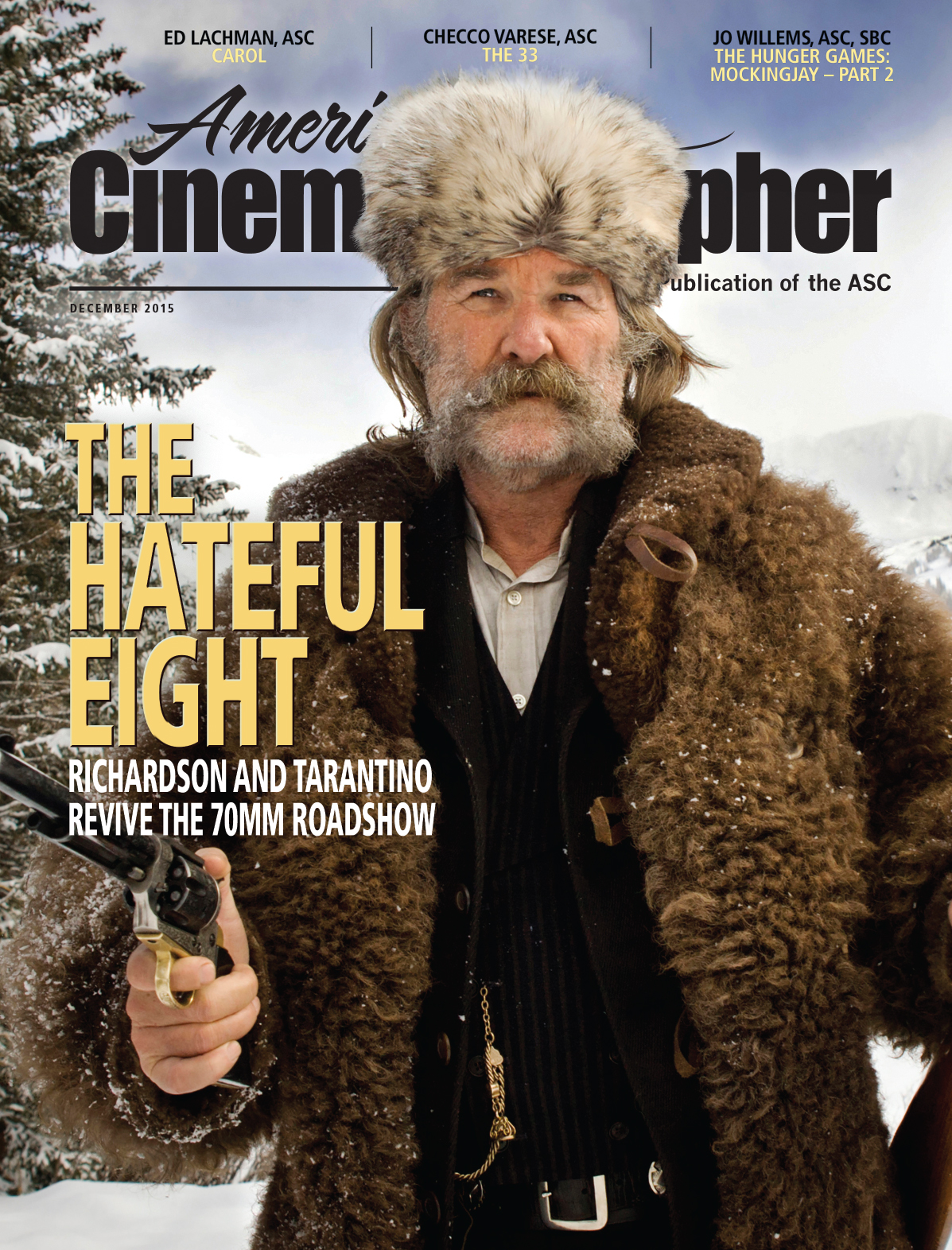

While cutting-edge cinema continued to impress with new options and opportunities, Quentin Tarantino sought something different for his brutal ensemble Western The Hateful Eight (Dec. ’15). He and cinematographer Robert Richardson, ASC embraced classic analog technology for the tale of pain and vengeance: Ultra Panavision 70, a 65mm film format that had not been used to shoot a feature since the 1960s.

“I thought maybe I could shoot it in a format that would demand that it be released [theatrically] on film,” Tarantino explained to AC. “If [the studio] is going to spend the money to shoot on 65mm, they’d want some sort of bang for their buck. So I figured we’d propose the big roadshow thing and see where we were after that. [I also felt] maybe we could show that 65mm wasn’t a lost cause. The excitement of the whole thing is that we might have accidentally bumped into a really good idea: the saving of film [for theatrical exhibition].”

It was a noble goal that stood to benefit cineastes and filmmakers — but first, Richardson had to investigate whether Ultra Panavision 70 was even a possibility for the production. After exhaustive research and testing, custom optics work by Panavision, and confirmation of film-stock availability from Kodak and lab services from FotoKem (one of the last facilities to process film), the filmmakers fell in love with the format. “[It] works well in a one-room situation because you can really utilize the stage and make it a ‘thing,’ creating a complete level of intimacy,” Tarantino explained. “And if you have eight or nine characters all trapped in one room, while I’m watching the people in the foreground where the scene is going on, I’m also seeing other people in the background. I’m always able to keep tabs on the characters in an almost theatrical-blocking sense.”

For the movie’s theatrical release, 100 U.S. theaters were refitted by Boston Light & Sound to project 70mm film, complete with custom projection lenses provided by Schneider Optics — capping a true team effort to realize a production’s full potential for impressing an audience.

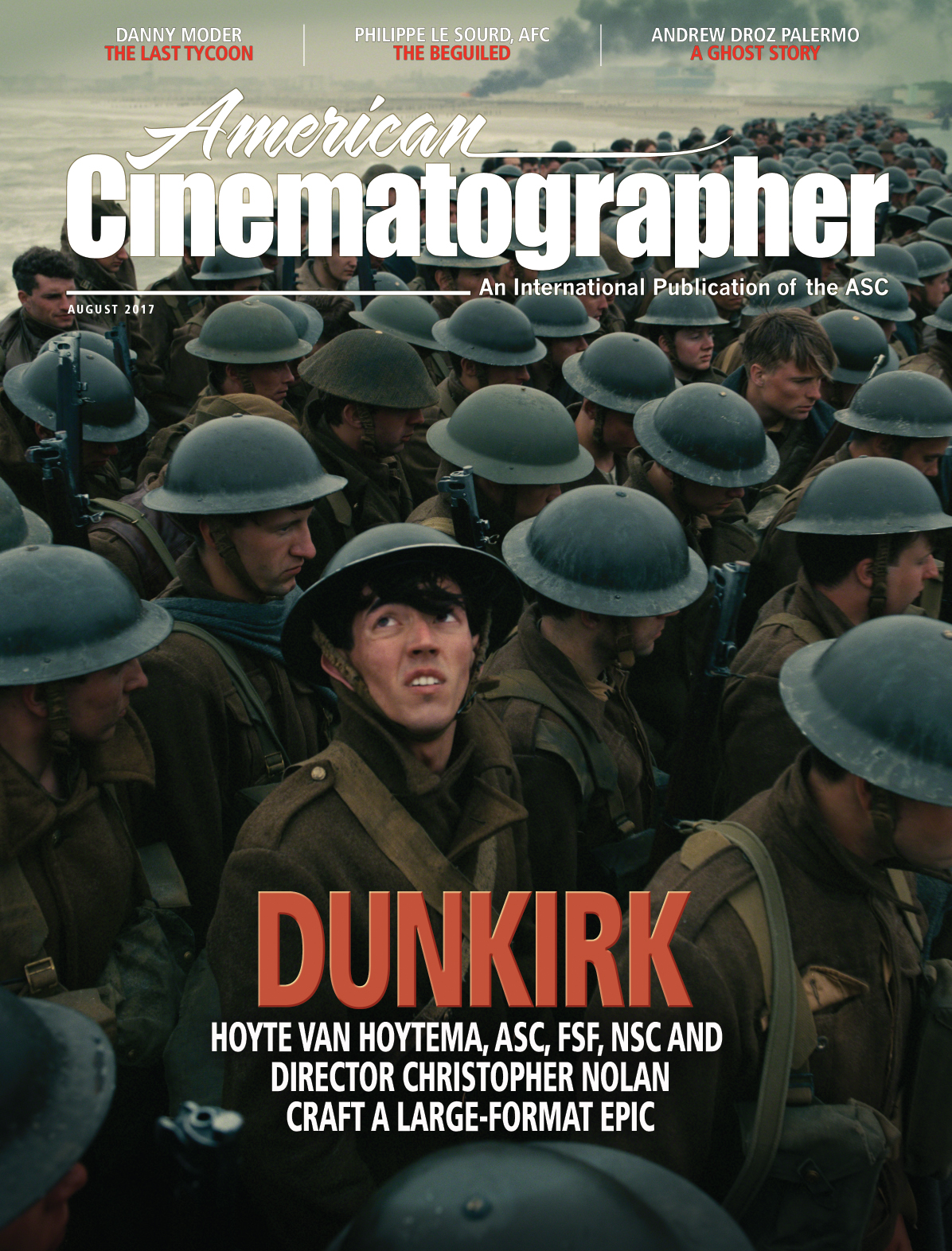

Similarly, Christopher Nolan sought an immersive, big-screen presentation for his World War II drama Dunkirk (Aug. ’17), for which he reteamed with Hoyte van Hoytema, ASC, FSF, NSC, following their intellectual space saga Interstellar (Dec. ’14). Along with Emma Thomas, Nolan’s partner and longtime producer, the duo made a presentation at the ASC Clubhouse during preproduction to lay out their ambitious plan to shoot on 65mm film (with Imax and Panaflex System 65 cameras), the highest-resolution capture format available. Dozens of ASC members attended the event, which included clips that had undergone a full photochemical finish and illustrated how the picture would look projected in 35mm, 70mm and Imax. In short, the filmmakers sought to push the technology envelope to deliver an extreme-fidelity experience, employing the tools they felt would best serve a dramatic story of survival and bravery. It was Nolan’s objective to “put the audience into the situation subjectively … to make them feel that they [are] running along the beach at Dunkirk, to make them feel like they are dogfighting from inside a Spitfire cockpit or on a small yacht sailing the English Channel.”

The filmmakers’ peers took note, and Dunkirk received Academy and ASC Award nominations for cinematography, among many other honors. The picture was also a global box-office hit, evidence that Nolan’s strategy struck a chord with audiences seeking new experiences. By pushing the film medium to its limits, Dunkirk reasserted the format’s viability, and the 100-plus-year-old technology remains a vital option for both production and exhibition.

In 2010, one of the decade’s most renowned cinematographers, Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC, transitioned from film to digital for the futuristic thriller In Time (Nov. ’11). “After doing a pretty comprehensive series of tests with the [Arri] Alexa, I thought it was the right tool to achieve the look we wanted,” he told AC. Initially “a little nervous about working with a digital camera,” he found the Alexa to be “a very intuitive, film-based system — it really feels like a film camera. The great thing about digital is that you can see the results on set while you’re shooting, which makes it easier to sleep at night.

“This moment has been coming for a long time, really, but with the Alexa I believe digital has finally surpassed film in terms of quality,” Deakins continued. “What is quality? It’s really in the eye of the viewer, but to me, the Alexa’s tonal range, color space and latitude exceed the capabilities of film. This is not to say that I don’t still love film — I do. I love its texture and grain, but in terms of speed, resolution and clarity of image, there is no question in my mind that the Alexa produces a better image.”

Deakins’ opinion instantly became news, sparking thousands of passionate articles, blog posts and discussion-board commentaries debating his point.

His subsequent picture, the James Bond adventure Skyfall (Dec. ’12), became the first 007 adventure to receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Cinematography — Deakins’ 10th Oscar nomination, as well as his third ASC Award win.

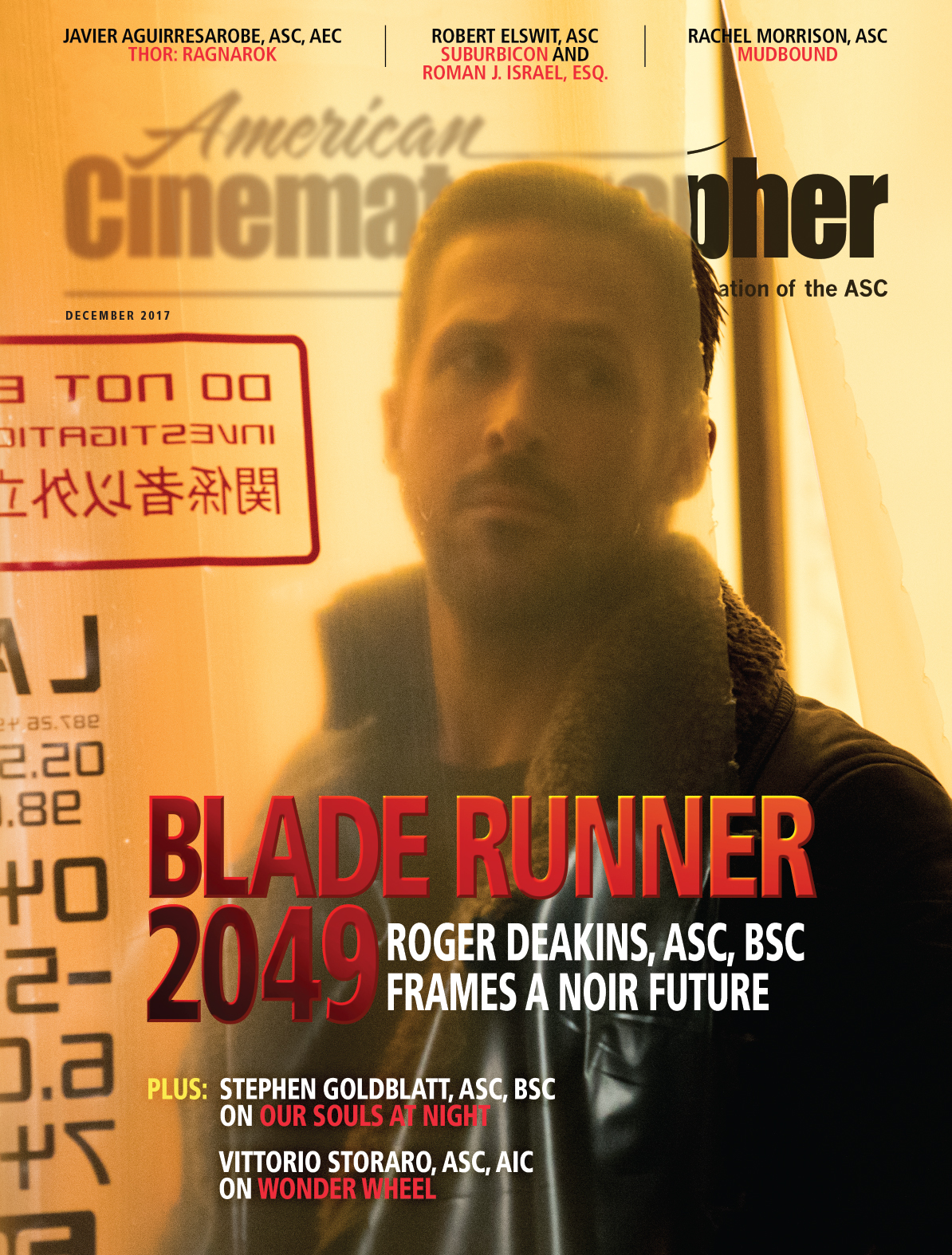

It’s not often that the Academy’s cinematography category is followed closely by the general public, but Deakins’ long record of excellence without a win prompted open discussion and debate. After back-to-back Oscar nominations for Prisoners (Oct. ’13), Unbroken (Jan. ’15) and Sicario (Oct. ’15), he finally took home the Oscar for his 14th nomination, Blade Runner 2049 (Dec. ’17), for which he also won the ASC Award. Directed by frequent collaborator Denis Villeneuve, the sci-fi sequel offered an intoxicating expansion of the dystopian realm depicted in Ridley Scott’s 1982 original, shot by Jordan Cronenweth, ASC.

Perhaps still reeling from Blade Runner 2049, audiences were further stunned by Deakins’ work on Sam Mendes’ World War I drama, 1917 (Jan. ’20), a storytelling marvel told in real time and in one seemingly unbroken shot (accomplished through expert planning, precise camerawork and exceptional visual effects).

Yet while Deakins’ work was lauded by many as an exceptional technical feat, he himself remained unmoved by this aspect of his work. As he once explained to AC, “You do need to be a technician at a certain level; you need some knowledge of the hardware and how it performs. But when it comes to the really technical stuff, you can always find people who know more about it than you do. That’s not my strength, and that’s not why people hire me.

“Cinematographers are hired for their eyes, for their artistic ability as visual storytellers, and for how they can run a set. Whether I’m shooting on film or digital, my job remains the same: to use the camera to tell the story the best way I can.”

With a multitude of cable channels and streaming services seeking to draw audiences, AC was there to document the “Platinum Age” of television that continued through the decade, often with detailed coverage direct from the set. A prime example was the location reporting on the fantastical Amazon Studios series Good Omens (June ’19), which called for intrepid AC senior editor Andrew Fish to travel to South Africa to interview cinematographer Gavin Finney, BSC; director Douglas Mackinnon; and renowned science-fiction and fantasy author Neil Gaiman. In this photo, the production turns up the heat while filming a scene featuring a fiery blaze. Cameras used on the show included Arri Alexa SXTs and Minis, as well as an Arri D-21 modified for hand-crank capture.

Other notable series covered included CSI: NY (March ’10), Boardwalk Empire (Sept. ’10), Fringe (March ’11), Game of Thrones (May ’12 and July ’19), Downton Abbey (March ’12), The Walking Dead (March ’12), American Horror Story (Nov. ’12), House of Cards (Feb. ’13), Chicago Fire (March ’13 and July ’18), The Americans (March ’14), Hannibal (June ’14), Vikings (March ’15), Daredevil (May ’15), Vinyl (March ’16), Empire (Oct. ’16), Mr. Robot (Nov. ’16), Penny Dreadful (July ’15), Preacher (April ’17), American Gods (Sept. ’17), Tales From the Loop (April ’20), Supernatural (March ’20) and The Crown (June ’20).

The past decade saw the rise of comic-book movies as a new, dominant genre — a modern-day equivalent of the Western, featuring heroes, thwarted villains and dramatic endings. Energized by cutting-edge visual effects, these morality plays present rich opportunities for cinematographers tasked with delivering memorable images that echo the illustrated source material. Features of the decade covered by AC include Iron Man 2 (shot by Matthew Libatique, ASC; May ’10), The Avengers (Seamus McGarvey, ASC, BSC; June ’12), The Dark Knight Rises (Wally Pfister, ASC, BSC; Aug. ’12), Guardians of the Galaxy and Captain Marvel (Ben Davis, BSC; Sept. ’14 and April ’19, respectively), Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (Larry Fong, ASC; April ’16), Wonder Woman (Matthew Jensen, ASC; July ’17), Black Panther (Rachel Morrison, ASC; March ’18) and Ant-Man and the Wasp (Dante Spinotti, ASC, AIC; Aug. ’18).

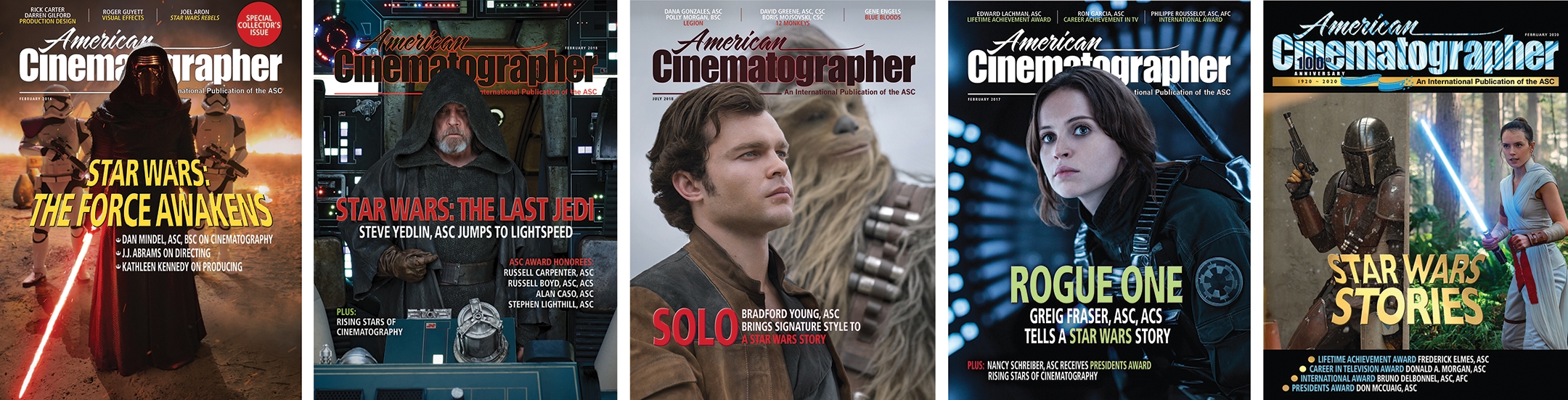

The Star Wars universe expanded greatly in the 2010s, with ASC members behind the camera on each project. AC featured extensive coverage not only of the sequel trilogy — The Force Awakens (shot by Dan Mindel, ASC, BSC, SASC; Feb. ’16), The Last Jedi (Steve Yedlin, ASC; Feb. ’18) and The Rise of Skywalker (Mindel, Feb. ’20) — but also the “Star Wars Story” spin-off features Rogue One (Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS; Feb. ’17) and Solo (Bradford Young, ASC; July ’18), as well as the groundbreaking streaming series The Mandalorian (Fraser and Baz Idoine, Feb. ’20).

Subscribe to American Cinematographer for access to the complete AC Archive — all 100 years of the magazine’s coverage, including every story referenced in this article.

Check here for more decade-by-decade breakdowns of AC’s 100 years.